The Woman Who Kept Anne Frank Alive Steps Into the ‘Small Light’

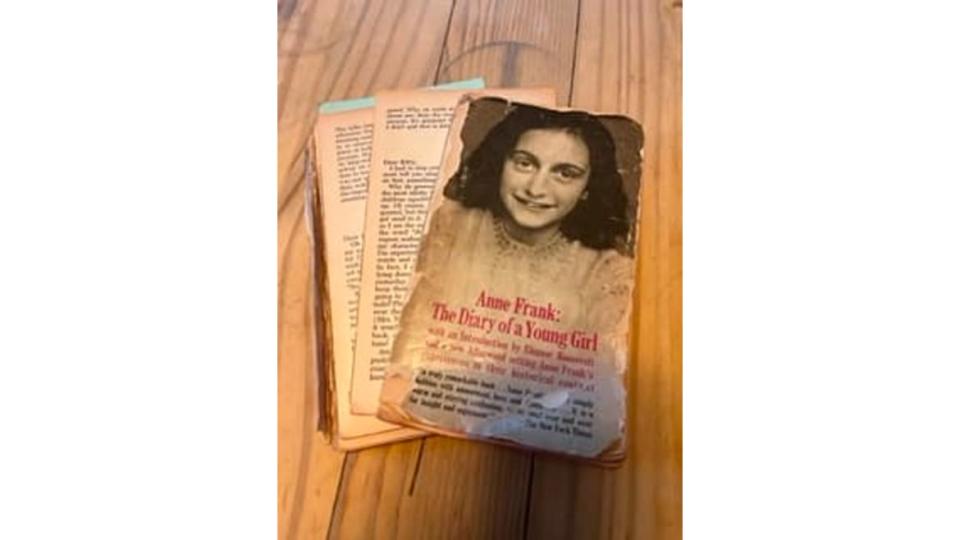

My copy of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl is in pieces, the brittle pages held together with a rubber band. It’s just a Scholastic paperback bought in 1969—on its 66th printing. This copy has been cried over, carted around the country, and reread many times, most recently after touring the sets built to replicate Anne’s world.

Years ago, returning from an assignment in Kenya, I scheduled a layover in Amsterdam to visit the Secret Annex. I waited hours in a drizzle to climb those steep, narrow steps to the 500 square feet where eight people hid from the Nazis. So, I’ve thought about Anne Frank—her words and her world that is no more—for over half a century.

Yet, while I recognized the name Miep Gies, I did not know what a hero she was until I heard about A Small Light.

Neither do most people, including Bel Powley (The Morning Show), who stars as Miep in the miniseries.

“I didn’t know anything about her is the honest truth,” Powley says, after a long day shooting on a dreary day in Prague. “I, of course, knew about the story of Anne Frank.”

The premiere—two episodes on National Geographic on May 1, then streaming the next day on Hulu and Disney+—was still six months away. And by now, she and Joe Cole, who plays her onscreen husband, Jan Gies, had bonded. They sit close to each other at a small table and acknowledge that as much as they have learned about these remarkable heroes, they’re still in awe of them and their bravery.

For 25 months, Miep smuggled food to Anne and the seven others in hiding with her. Miep defied the Nazis and risked death.

It’s not much of a spoiler to say that the Nazis hauled off everyone in the attic toward the war’s end. After, Miep snuck back upstairs, collected Anne’s diaries, and put them in a drawer for safekeeping. She planned to return them to the girl after the war.

Anne Frank died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. She was 15.

Eventually, Miep presented the journals to the only surviving member of the Secret Annex, Anne’s father, Otto Frank, who published them. They have been translated into 70 languages and sold about 30 million copies.

Had Miep Gies not been there daily, Anne Frank’s writing would have been lost.

A Small Light is the story of this remarkable woman who maintained that she was anything but. The title references Miep’s famous quote: “I don’t like being called a hero because no one should ever think you have to be special to help others. Even an ordinary secretary or a housewife or a teenager can turn on a small light in a dark room.”

Miep Gies, played by Bel Powley, Otto Frank, played by Liev Schreiber, and Jan Gies, played by Joe Cole, look up at Otto’s old apartment as seen in A Small Light.

An Ordinary Person

Incidentally, Miep was not Jewish, but the actress who plays her, Powley, is.

“I identify as Jewish,” Powley says. “I was raised Jewish. My dad isn't Jewish. But my mom, she was raised in a pretty Orthodox household.”

Powley grew up celebrating the Jewish holidays at her grandmother’s. Like most European Jews, Powley knew her history; it’s never that far removed.

“The offer of this actually came to me on Holocaust Memorial Day, which was so special,” she says, those huge blue eyes unblinking. “Before I even read the pilot, I already knew it was something that I wanted to be a part of, and it just feels so special to be a part of this story and be able to play this character because of my heritage.”

Joan Rater and Tony Phalen were fascinated by Miep’s selflessness. They saw a documentary, Anne Frank Remembered, about Miep in 1996. On a family trip to Amsterdam, they toured the Anne Frank Museum. These eight hours, which don’t dip into the maudlin or sanctify Anne, are the product of six years of research.

They serve as co-executive producers, co-showrunners, co-creators and writers, and Phelan directed the final three episodes. Gies’ unwavering courage still impresses them.

“Miep is an ordinary person who history has mythologized like Anne Frank,” Rater says. “I want to tell the story about the ordinary person.”

Despite her heroism, Miep was decidedly ordinary. She was starving in Vienna after World War I when, as a child, her mother sent her to the Netherlands to be nurtured back to health. When Miep graduated high school, she was a bit feckless for her foster parents’ liking. They told her she had to get married—to her gay, also adopted brother. Instead, the two decided she’d get a job.

That’s how Miep came to know the Franks. She had no experience, but Otto took pity on her and hired her at his company, Opekta, at Prinsengracht 263. As the Nazis made life more miserable for Jews, Otto tried vainly to spirit his family to safety. When daughter Margot, 16, received papers to report to a camp, the family went into hiding in the attic that day.

Miep chats with the Frank and van Pels families in the secret annex.

Everyone—the four in the Frank family, Otto’s business partner, his wife and son, and a family friend—were safe for over two years. Miep and her husband Jan (Joe Cole, Peaky Blinders), another hero of the Dutch Resistance, did all they could. Meanwhile, Anne chronicled everyone’s annoying habits and confined life in her journal.

And it’s through that writing Anne became the most famous Holocaust victim. We can relate to one girl, not to the inconceivable number of 6 million people murdered for being Jewish. We know Anne because of diary entries such as: “I can shake off everything if I write; my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn. But, and that is the great question, will I ever be able to write anything great, will I ever become a journalist or a writer? I hope so, oh, I hope so very much, for I can recapture everything when I write, my thoughts, my ideals, and my fantasies.”

Doing Extraordinary Things

Of course, it all ends dreadfully. And yet the series offers glimpses of lightness. In a flashback to the sunny day of Miep and Jan’s 1941 wedding, Anne’s skipping. It’s a reminder that she was an ordinary tween—albeit a terrific writer—in an extraordinary time.

“She was just a girl who did cartwheels, and then she was put into hiding,” Rater says. “And so, the ordinariness is always something that remains. Oh, here's the other thing that blows my mind and I relate to as a parent—when Otto says in an interview that when he read the diary, he didn't recognize this girl.”

By now, though, the rest of us do. Phelan and Rater didn’t want to do yet another movie about Anne, here played with just the right amount of teen diva and wise old soul by Billie Boullet. Older sister Margot, a quieter, nervous girl, is portrayed by Ashley Brooke, who drew from her grandmother’s experience as a Holocaust survivor.

“My grandma lived to the age of 96, and she passed away about a year and a half ago,” Brooke says. “The USC Shoah Foundation interviewed her, which is actually crazy that I'm [a student at USC] now. Before this project, I watched her interview because when she got older, she started forgetting things, so she couldn't really tell the story to us. But those interviews were so special, and I just remember her highlighting all of the hopeful moments that allowed her to survive. She was never pessimistic about anything.”

A Modern Take on Anne Frank’s Holocaust Saga Wows Cannes

All of this rings true—performances, costumes, eerily spot-on sets, and the unbearable weight on Otto’s shoulders.

“It was actually a pretty small role, and I was in Ukraine, and they sent me this,” says Liev Schreiber of playing the patriarch. “And I thought, wow, this is a really contemporary retelling of the Anne Frank story but from a completely unique perspective of the person who’s actually responsible for them surviving as long as they did. It was one of those things that I was thinking about as I was going to meet these grassroots NGOs in Ukraine—like ordinary people who are doing extraordinary things to push back against incredible odds. And it felt like the script fell in my lap while I was doing that work and meeting those people.”

Schreiber has been volunteering in Ukraine, his Jewish grandfather’s homeland. He sees folks with Miep’s courage and praises Phelan and Rater for making the limited series feel as if it’s not entombed in amber.

Anne, played by Billie Boullet, receives a gift from Miep, played by Bel Powley, in A Small Light.

The Modern-Day Impact

One of the subtle ways the miniseries feels contemporary while hewing to history is through each episode’s closing credits. Current artists cover old music, courtesy of Este Haim of the sister band, Haim. Serving as executive music producer, she chose Kamasi Washington, who performs Charlie Parker’s “Cheryl,” and the pairing of King Princess and Orville Peck, who contribute a take on Bing Crosby’s “I’m Making Believe,” among others.

Also Jewish and keenly aware of the parallels between World War II and the antisemitism of today, Haim acknowledges, “I would be lying if I said there weren’t times where I felt really scared in 2023. It’s almost 100 years later, and we're still dealing with this shit.” This tiny woman who stood up to the Nazis wows her. As Haim notes, Miep was “a badass.”

Miep eventually wrote a memoir which Powley considered her Bible while shooting this.

“I read it back-to-back three times before we started, just to get a sense of her voice because it's written from her point of view, and you really can get just how she was quite outspoken and brash and confident and funny,” Powley says.

The shoot took five months, mainly in the Czech Republic, with Prague standing in for Amsterdam. Working on the project left its mark, all involved say. Independently, they mention how they hope Miep’s example inspires people to act even against unspeakable evil.

“This is so unbelievably horrendous,” Cole says. “It's just, like, I sometimes just can't quite comprehend. When I visited Anne Frank’s house, you see a lot of the imagery, young Margot, you see the pictures on the walls, being in that space.”

Anne, played by Billie Boullet, sleeps as Miep, played by Bel Powley, watches over her in A Small Light.

Powley sits quietly next to him, nodding. The cast and crew have been talking about how rampant antisemitism is. The same October day, when they were finishing a scene in Prague, Jew-haters on an overpass of the 405 in Los Angeles hung a banner that said Kanye was right as they gave the Hitler salute.

“I don’t think that you feel less being gentile,” Powley says. “But I think that it’s just terrifying right now.”

The sense of terror thrumming through Jewish communities then is again felt.

The day I wrote this, I attended an interfaith Holocaust memorial service, where a man told of his parents, who met in the camps. Like the Franks, they were from Amsterdam.

At the service, I ran into a friend, Holocaust survivor Hanna Keselman, 93. Like so many German Jews, Hanna’s parents knew Hitler was dangerous long before the rest of the world caught on. In 1933, they fled to France. It wasn’t far enough. She was on her own at 8—for four years. Hanna lost her father to the war and later moved to America.

Anne Frank’s Stepsister Eva Schloss on Holocaust Horrors and How Trump Reminds Her of Hitler

She still tells her story today because no one must forget what happened—and what is happening. Two days before the service, anti-Jewish graffiti popped up—in Greenwich Village.

Haim is right. It is scary.

“I was blown away by how modern and current and relatable Tony and Joan’s take on this story felt,” Powley says. “And that’s incredibly important in the current political climate. I mean, antisemitism is on the rise. There are more displaced people in the world now than ever. So, it was important to me and for my family history that, if we’re going to make this show, to make one that makes people think, ‘Well, what would I do?’”

Keep obsessing! Sign up for the Daily Beast’s Obsessed newsletter and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

money

money