Wings of change: Long before United, Black pilots flew freely in American skies

Nearly 30 years before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered the “I Have A Dream” speech from the nation’s capital, Army Lt. William Powell shared his own dream for America: one where Black people shed the shackles of racism and spread their wings to fly.

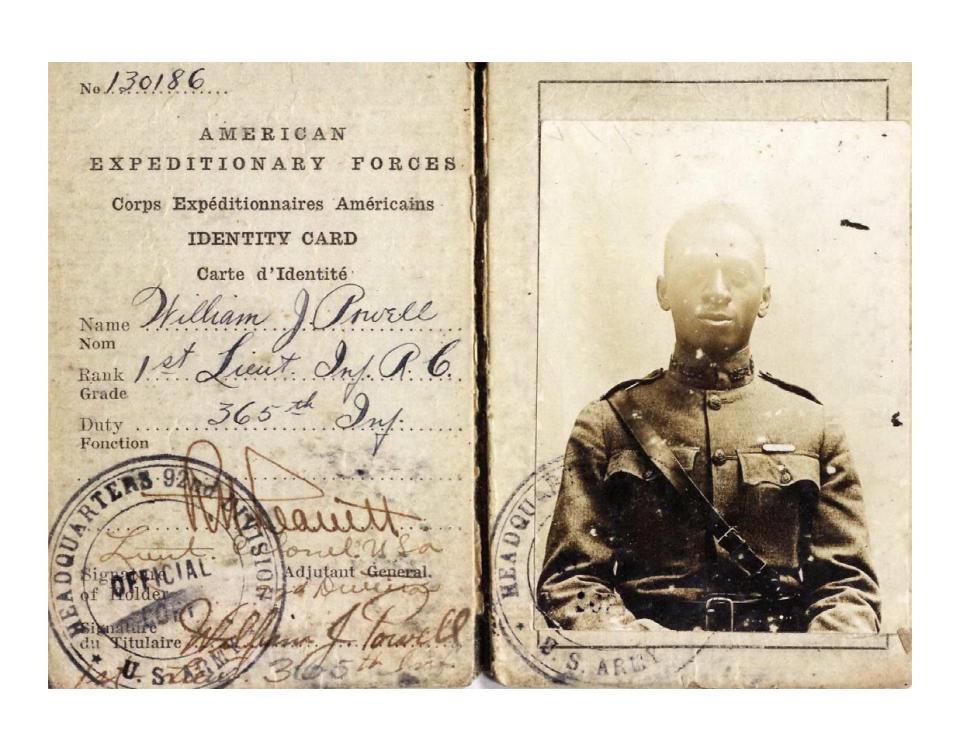

The former Army infantryman fell in love with aviation during his stint overseas in World War I and in 1932 became one of the rarest people in the United States: a Black man with a pilot's license.

Powell’s semi-autobiographical book "Black Wings," published in 1934, exhorted Black youth to seize the freedom and opportunity of air travel as he did.

“Fill the air with black wings,” he wrote.

But almost 90 years later, Powell’s dream remains one deferred. Though Black pilots have been flying almost since there were planes to fly, those wanting to break into aviation and the aerospace industry in the 21st century still face the same obstacle of racism that was present at the turn of the last century.

According to 2020 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 94% of the country’s 155,000 aircraft pilots and flight engineers identified as white. Only 3.4% were Black, with just over 10% combined of pilots and engineers listed as Black, Latinx (5.0%), or Asian (2.2%).

Women make up just 5.6%, with Black women representing less than 1% of that total. That adds up to only about 150 Black women on flight decks every year.

“I think the numbers make pretty clear that there is a lot of room for improvement,” said Joel Webley, a National Guard and FedEx airline pilot who currently chairs the board of the Organization of Black Aerospace Professionals (OBAP).

But when United Airlines announced a plan last month to train and hire more people of color and women to be pilots to improve diversity – at least half of its 5,000 new recruits over the next decade – it met with swift backlash from some in conservative circles.

More: Astronaut Michael Collins, a pilot on Apollo 11's mission to the moon, dies at 90

More: What's the process for pilots returning to flight after COVID-19? What's involved in retraining?

Fox News’ Tucker Carlson, for example, claimed training more minority candidates would lead to lower aviation standards and “get people killed.”

“You realize that everybody does not feel that we should be there,” said Capt. Theresa Claiborne, the first Black woman pilot in the Air Force and the most senior officer with United Airlines.

Claiborne runs an organization, Sisters of the Skies, which specifically targets young Black women to help create a new pipeline for aspiring Black pilots.

“That's one of the reasons why I say that my job – Theresa Claiborne's job – is to be the best captain I can be,” she said. “To represent my company, to represent Black people, to represent Black women to show that, yeah, we do this job.”

Flying from the beginning

Resistance to the notion of Black pilots started as early as the achievement of flight itself, which happened in a time when wide swaths of America still lived under legal segregation.

Decades before Powell penned his book encouraging his people to reach skyward, Black Americans who wanted to fly had to leave the country to learn the craft. No U.S. flight school or military air service would accept them.

They included Eugene Bullard, a Georgia native born to former slaves who sought a new life in France and enlisted in the French Foreign Legion at the start of World War I. He then joined the country’s air force and earned his wings in 1917, becoming the first Black fighter pilot in history.

But when he tried to return home and join the U.S. Air Service when America entered the war that same year, his application was denied, despite his qualifications, due to his race.

Three years later, Bessie Coleman, the daughter of Texas sharecroppers, followed Bullard’s footsteps to France after being unable to find flight training in the United States because of her race and gender.

After earning acceptance at a prestigious flight school there, Coleman became the first licensed woman aviator of either Black or Native American descent in 1921.

More: Airlines: Book your flight now, pay later

She returned to the United States and won acclaim as a show pilot until she died in a plane crash in 1926 – the same year Canton, Oklahoma native James Herman Banning became the first Black pilot to earn his license through the United States Department of Commerce.

Powell was faced with a similar choice after being rejected by flight schools near his home in Chicago and by the Army’s Air Corps (now the Air Force): pursue his pilot license in France or fight to break through in states as Banning had done.

The former infantryman chose to try his luck in his home country and finally found a place willing to train him in 1928: the Los Angeles School of Flight.

Within four years, he had earned his pilot license within the United States, sponsored the first ever All-Black American air show, and started an aviation club in honor of Coleman that welcomed people of all races and genders.

Before Banning and Powell, the first Black man to get a pilot’s license on U.S. soil was actually categorized as white — at least on paper.

Less than a decade after Wilbur and Orville Wright flew the first airplane from Kitty Hawk in North Carolina, Emory Malick received his International Pilot's License in 1912 after studying at the Curtiss School of Aviation in San Diego. He is thought of as the first pilot of African descent in the United States, though this distinction is somewhat controversial.

Malick’s grandniece, a white woman named Mary Groce, uncovered an old photo of Malick in which he appears to be Black or of mixed race – a family secret, Groce has said. Public records from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where Malick once lived, state he and his family identified as white.

But Dorothy Cochrane, curator for general aviation at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, says accounts from other pilots who flew with Malick offer enough evidence to confirm his Black ancestry. "At this point, we believe he is the first African American pilot."

It wasn’t until the outbreak of World War II that the U.S. began routinely training Black military pilots and mechanics, setting the stage for the famed Tuskegee Airmen to make history in 1941 as the first Black fighter pilots in American history.

Seven years after the Airmen officially entered the war effort, President Harry Truman signed an executive order desegregating the U.S. military in 1948.

Cochrane says the Airmen's success made it possible.

"Their combat missions, their training, all of their ratios were the same as white pilots. They were decorated, they were respected," she said. "There was no reason not to keep it going."

The wings of modern flight

While the Tuskegee Airmen and the aviation pioneers before them cleared the runway for the next generation of Black pilots, entrenched racism and Jim Crow conspired to keep Black wings from reaching the skies for decades.

Despite the desegregation of the military, Jesse Brown, who became the Navy’s first Black fighter pilot in 1948, dealt with both covert attempts to disqualify him during flight training as well as overt aggression from white superiors.

At one point, Brown’s brother Fletcher recalls, one flight training instructor said he’d rather kill himself and Brown in a plane crash than see Brown become a pilot.

Outside of the armed forces, Black pilots were denied jobs in the commercial airline industry until 1964, when American Airlines hired Capt. Dave Harris.

“After rejections from several other major airlines at the time, Harris wanted to avoid any misunderstanding down the road,” according to a 2008 American Airlines press release announcing special honors for Harris, who retired after 30 years of service in 1994.

“‘Following his interview with American,’ Harris recalls, ‘I felt compelled to tell [the interviewer] I was black,’” the press release said. “The chief pilot who conducted the interview responded, ‘This is American Airlines and we don't care if you're black, white or chartreuse, we only want to know, can you fly the plane?’”

Five years later, Woodson Fountain – once an aspiring military pilot who got his first plane ride from Tuskegee Airman Major Charles Dryden – broke the same barrier at Northwest Airlines, which is now part of Delta Airlines.

Fountain said he was the first Black pilot to join the company when he started in 1969. Industrywide, he said, only about 80 Black pilots were in the skies at the time.

It’s been more than 50 years since Fountain flew his first plane; he’s now 80 and retired. But he said the representation problem in the aviation industry remains far from solved, which is why United’s current plan is “nothing but good” for prospective pilots.

“I think the applicants are going to be very, very motivated to do anything to become a pilot,” he said. “[United Airlines] needs pilots, and I think they are aware of the lack of representative number of African American and women pilots and are going to do the best they can to improve those percentages. Hats off to them, I think that’s fantastic.”

Webley agrees, noting that the benefits of a more inclusive talent pool go both ways.

“Diverse organizations show higher levels of innovation and earnings,” he said. “Many companies shy away from this argument for diversity because they fear being accused of ‘doing diversity’ for the wrong reason. I think that's the wrong approach — it needs to become widely known that diversity makes good business sense.”

Webley and Claiborne’s outreach efforts through OBAP and Sisters of the Skies aim to take advantage of an expected aviation boom following the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’re just now getting enough exposure so that young Black girls and boys are able to look and see people that look like them doing something they never thought that they could do,” Claiborne said. “It’s a beautiful thing.”

Their concerted efforts to create opportunities for aspiring Black pilots could bring the dream Powell laid out in "Black Wings" to fruition even as the aviation industry recovers from the pandemic.

“There is a better job and a better future in aviation for Negroes than in any other industry,” Powell wrote, “and the reason is this: aviation is just beginning its period of growth, and if we get into it now…we can grow as aviation grows.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: United Aviation Academy seeks diversity, to recruit more Blacks, women

money

money