Why the sinister Shadow of a Doubt was Hitchcock’s favourite Hitchcock

“The whole world is a joke to me,” claims Joseph Cotten as the villainous Uncle Charlie in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 film Shadow of a Doubt. Central to this celebrated, tense film is an alarming streak of pessimism, one inhabited brilliantly by Cotten’s unnerving and irredeemably nasty character. Yet suave Uncle Charlie was arguably also an expression of its director’s inner persona. As Hitchcock once put it: “a glimpse into the world proves that horror is nothing other than reality.”

It is fitting then that, over the years when quizzed about which of his 50 or so films was his personal favourite, the choice was one that concerned murder. As suggested several times throughout his life, Hitchcock’s favourite Hitchcock was Shadow of a Doubt.

Shadow of a Doubt charts the increasingly tense visit of Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) to his sister’s (Patricia Collinge) family in a sleepy part of Santa Rosa. Charlie fled his previous town after the police got too close, with suspicions surrounding him concerning a recent spate of murdered rich widows by the so-called “Merry Widow Murderer.” Uncle Charlie is particularly popular with his niece Charlotte (Teresa Wright).

But, as the exciting days of her uncle’s visit pass by, Charlotte becomes increasingly suspicious of his past, especially when an undercover detective (Macdonald Carey) warns that her favourite uncle may not be all that he seems. Hitchcock builds tension by teasing the audience as to whether Charlotte will believe the truth in time to save her.

Scripted by playwright Thornton Wilder, the film’s narrative owes its heritage to real-life murderer Earle Nelson. America’s first known serial sex-murderer of the 20th century, Nelson preyed on older landladies along the East Coast in the 1920s; posing as a meek-mannered lodger before sadistically murdering and assaulting them. With a known 22 killings to his spree of barely a year before he was caught and executed, Nelson is still considered one of the most prolific murderers in American criminal history.

The sheer nastiness and scale of the crimes, along with ghoulish headlines, such as “’Smiling Stranger’, Sighted at Death Scene by Mail Carrier…” and “Finds Mother Murdered in Attic Trunk”, clearly influenced Hitchcock’s leering Uncle Charlie; the film germinating barely 15 years after the crimes hit the newsstands. From Charlie’s chosen victims to his method of killing (manual strangulation), Nelson and the character share a stark number of similarities. Both comfortably earn the title of “Merry Widow Murderer”.

This grim real-life inspiration initially came from the story department of producer David O Selznick. “The head of Selznick’s story department had a husband who was a novelist,” Hitchcock told French director François Truffaut in their famed book-length interview. “One day she told me her husband had an idea for a story but he hadn’t written it down. So, we went to lunch… and they told me the story. In this way we got the skeleton of it into a draft that was sent to Thornton Wilder.”

One of the reasons Hitchcock wanted Wilder was because he aimed to capture the sense of life in a small town. Having watched Wilder’s play Our Town (1938), Hitchcock later approached the playwright with the idea of the film. It was vital to Hitchcock that the story showed an almost devilish villain entering a cosy, picture-postcard America. According to Hitchcock’s daughter Pat, this was one of the reasons why he was so proud of the film. “This was my father’s favourite movie,” she said, “because he loved the thought of putting menace into a small town.” There was, however, a problem.

America had recently entered the Second World War and Wilder at the time was only weeks away from commencing military duty. Though Wilder worked tirelessly with the director, they did not finish the script on schedule, so Hitchcock travelled with him across the country by train to where the playwright was being stationed, finishing the draft on the long coast-to-coast journey. With later additions provided by Alma Hitchcock and screenwriter Sally Benson, the script was soon complete. Fittingly, Wilder himself enlisted in the Psychological Warfare Division of the U.S. Army and was soon to be unleashing many a tense evening upon the minds of the enemy rather than cinema audiences.

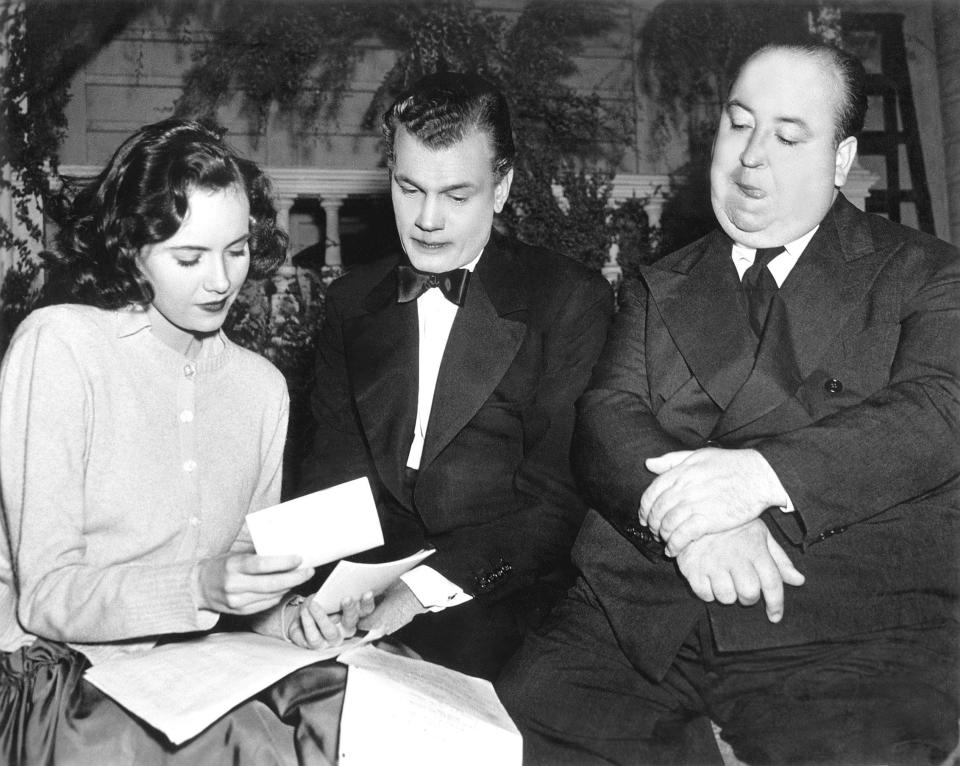

With the script in place, the film seemed fully formed straight away. In 2013, Teresa Wright recalled how Hitchcock virtually performed the whole film for her to get her on board, having her loaned out from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. “What I remember more than anything,” she recalled, “was going into his office where he told me the story of the film. He told me it so minutely that when I eventually went to see it, I thought ‘I’ve seen this film before. I’ve seen it in his office.’”

The filming was a happy experience, according to Wright, contrary to the experiences of Hitchcock’s later leading ladies such as Tippi Hedren who, like a number of his lead actresses, he bullied and obsessed over on the set of The Birds.

“He was so much fun,” she said of the director, “as was Joseph Cotten. It was like a family. A very happy experience.” However, Hitchcock was reluctant to speak publicly about working with his leading man. When asked why Cotten wasn’t a regular performer for the director, especially considering the actor’s success as Uncle Charlie, Hitchcock cryptically replied: “Oh, I’m a Capricorn.”

What Hitchcock may have been channelling was his frustration at not getting the lead he originally wanted. Actor William Powell was Hitchcock’s first choice for the role but, unlike with Teresa Wright, MGM refused to loan Powell out, so Cotten was cast. Still, Hitchcock would work with Cotten again on the 1949 film Under Capricorn as well as in one of the great episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Breakdown (1955).

Whatever the relationship was between director and star, the results in Shadow of a Doubt were astounding. Uncle Charlie became one of the great American screen villains: smooth-talking yet sly, a mask of utter charm hiding something malicious beneath. Cotten’s Charlie makes the film and, tellingly, Cotten reprised the role twice for radio, in 1943 and 1946.

In particular, the way Hitchcock chose to shoot the film had an impact on both the final results and his later work. In what feels a dry-run for Psycho, Hitchcock frames Shadow of a Doubt more from the villain’s point of view rather than the hero’s. Cotten’s character fills the screen time and, when his false persona collapses, Hitchcock almost breaks the fourth wall. It’s as if Uncle Charlie is talking to the audience itself, trying to convince us of his beliefs as he turns to the camera during a troubling and famous monologue.

Uncle Charlie’s monologue is a long spiel about his hatred of women, one that pours forth from him by chance over dinner. “Are they human,” he asks when challenged about his views on rich widows, “or are they fat, wheezing animals? And what happens to animals when they get too fat and too old?” His eyes are unblinking as he turns to the camera during the monologue. It was a masterstroke of menace.

Was Uncle Charlie really a cipher for Hitchcock’s own misanthropic worldview? Such darkness is most overt in another terrifying speech where Uncle Charlie decries to his niece “Do you know the world is a foul sty? Do you know, if you rip off the fronts of houses, you'd find swine? The world’s a hell.” The French film director François Truffaut suggested this could actually be Hitchcock, writing that it “is obviously Hitchcock expressing himself in Shadow of a Doubt when Joseph Cotten says the world is a pigsty.”

For a director who famously labelled his actors “cattle”, it is hardly a step too far to believe he was expressing his disdain for the world around him, in particular the film industry. After all, Hitchcock often spoke with frustration about the actual filming process, suggesting that it was more in scriptwriting where he found creative satisfaction. Tellingly, Hitchcock’s famous list of three essential things required for making a good film consisted of “the script, the script and the script.” And Hume Cronyn, who made his debut in Shadow of a Doubt, even recalled that Hitchcock found filming rather a chore, remembering that “he used to say on set that the actual filming was so boring”.

When quizzed by Truffaut about the empathy shown towards Uncle Charlie in the film, Hitchcock admitted that the character was “a killer with an ideal; he’s one of those murderers who feel that they have a mission to destroy… There is a moral judgement in the film.” The judgement comes from effectively making Charlie the anti-hero, an unusual but effective move that creates some of the strongest pathos of the director’s career.

Perhaps it was this sense of personal release that meant the film, in hindsight, stood out for the director. There’s certainly a vicious joie de vivre about Uncle Charlie who seems to relish his own evil machinations. It’s easy to imagine Hitchcock giving a wry smile as he planned and realised some of Charlie’s more deliciously dark scenes.

In the director’s later years, he finally admitted his affinity for this brutal production, in spite of denying it in earlier years. When asked by Dick Cavett in 1972 which of his films he would save if only allowed one, he chose Shadow of a Doubt. “I liked it very much,” he said, “because it was true. It was a character picture.” Whether the character in question was Uncle Charlie or Hitchcock’s is debatable. But one thing is for certain: it resulted in a masterpiece of suspense that still terrifies to this day.

money

money