Why Some People Think 2+2=5

Former mathematician Kareem Carr says it’s important to know what your math is abstracting for you.

People are always ready to argue about math on Twitter.

Carr applies his math knowledge to study human genetic markers of cancer at Harvard.

Critical armchair mathematicians are having a moment after a thread about the created nature of numbers spread on Twitter.

Kareem Carr, a biostatistics Ph.D. student at Harvard University, says that sharing his ideas about numbers and abstraction to a large audience on Twitter helps him find others who think differently and are excited about connecting theory to reality.

➗ You love numbers. So do we. Let's nerd out over numbers together.

And while some bad-faith critics have flooded his notifications with unkind assumptions, he’s still happy to put his ideas out there.

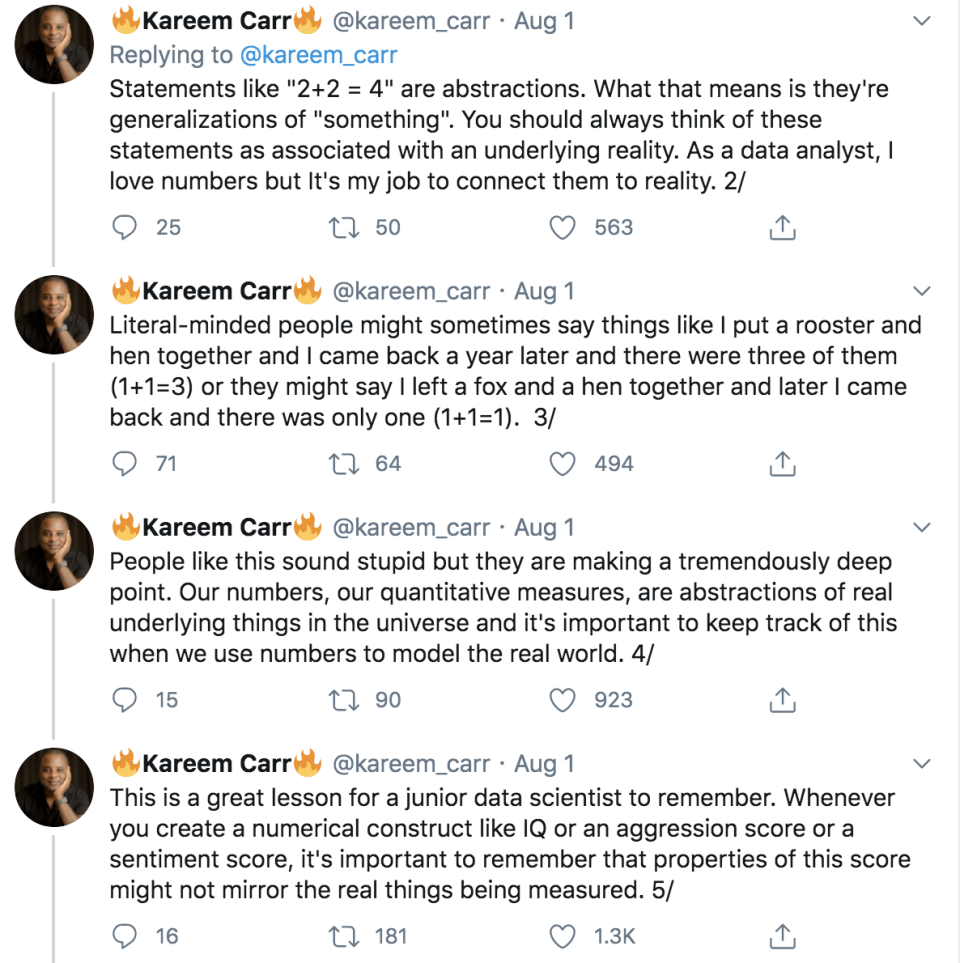

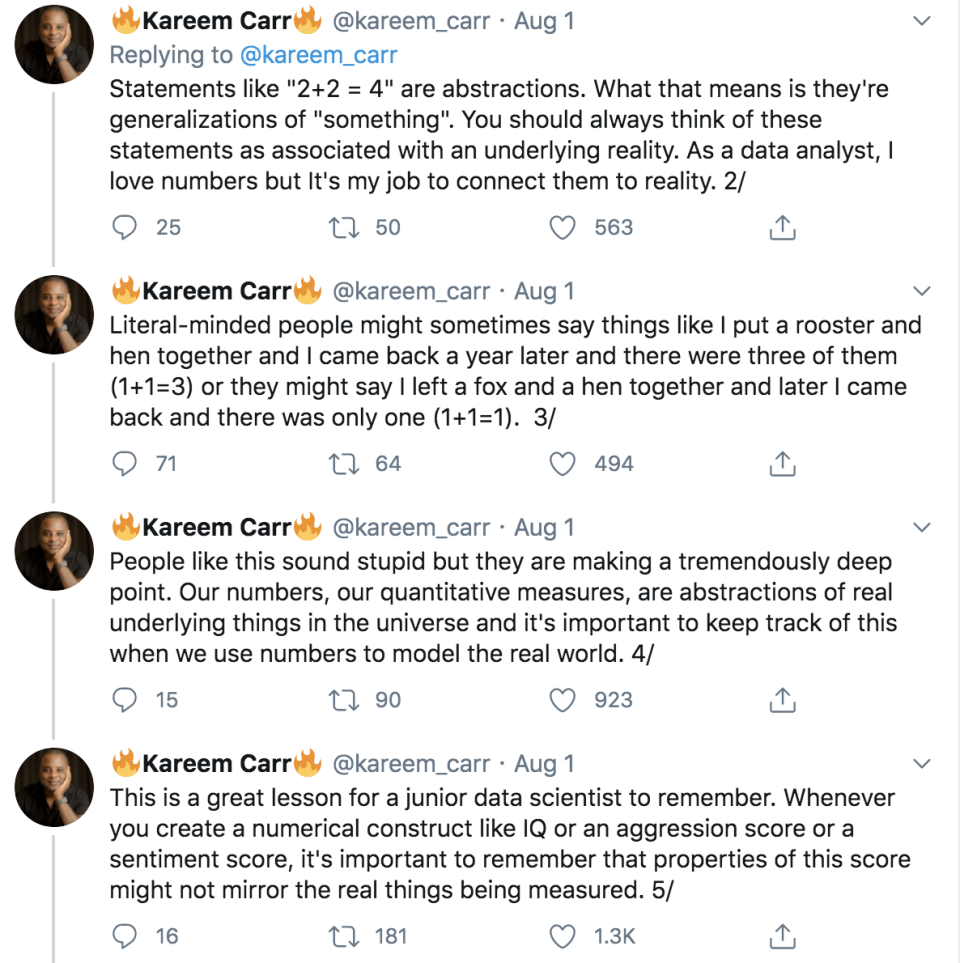

EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT "2+2=5". As a former mathematician, I have things to say. 1/🧵

— 🔥Kareem Carr🔥 (@kareem_carr) August 2, 2020

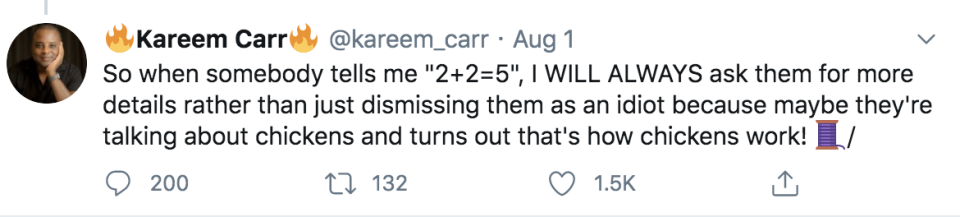

In his original thread, Carr points out some simple, but provocative truths about the world. “Our numbers, our quantitative measures, are abstractions of real underlying things in the universe and it’s important to keep track of this when we use numbers to model the real world,” one tweet reads.

Carr grounds it in the real ways statistical models are being used to harm, for example, marginalized groups across many parameters: “Whenever you create a numerical construct like IQ or an aggression score or a sentiment score, it’s important to remember that properties of this score might not mirror the real things being measured.”

“There’s a need for this sort of thinking, because we’re basically turning everything into data,” Carr tells Popular Mechanics. “Because we’re turning more and more domains into data, it's becoming more and more important. If we’re going to be a world that’s just in apps, we need to be sure these things are working how we think they work.”

✓ Extra Credit

❏ Revisit the infamous triangle problem that divided Pop Mech’s editors and readers.

❏ Discover the truly amazing math behind the Rubik’s Cube (and learn how to solve it).

❏ Dive deep —and we mean deep—into our fun math features.

Carr hasn’t said anything really controversial here, unless just saying mathematically nuanced things is inherently controversial on Twitter. The idea that the counting numbers—whole values only, excluding fractions and decimals—are somehow “naturally occurring” is a common fallacy among people who aren’t trained in math or, say, human development.

Babies acquire numbers one at a time and top out at a handful unless their families and teachers introduce larger and continuously countable numbers to them. Some non-human animals demonstrate an ability to “count” up to four or five and are considered exceptional even for this.

There’s also a language assumption at play, what novelist China Mieville has called an “unpersuasive notion of language as a clear pane of glass.” Everything we say and write is mediated through, well, a medium. The same way recorded music necessarily lops off the most extreme highs and lows by nature of technology, the terms we use are approximations that can never be totally true to what we think or feel, what we see, and how the world appears.

How music is recorded and compressed is a model. Language is a model, mathematics is a model, and troubled metrics like IQ are models, too. It benefits no one—or, perhaps, only the people in power—to pretend they’re universal truths instead of engaging with the consequences of each model.

Carr says he’s always been interested in the interaction between the “pure” mathematics and where those ideas are actually applied—in a sense, the colorful pane of glass we install in order to view math in our lives. “Here’s this thing off to the side and it’s called math. And over here you have real life, scientific method, and concrete things that are happening in the physical world,” he explains.

While studying pure math, he grew frustrated by the combination of abstraction and fallible human conclusions—no one’s fault, he says, just a mismatch in interests. So he began working in and studying biostatistics, analyzing genetic sequencing data collected from patients and looking for markers of cancer.

That’s what he’s still doing now, and his exciting thesis, which combines his interests into a very clever answer to a statistical question, will be published next year.

You Might Also Like

money

money