White landowners in Hawaii imported Russian workers in the early 1900s, to dilute the labor power of Asians in the islands

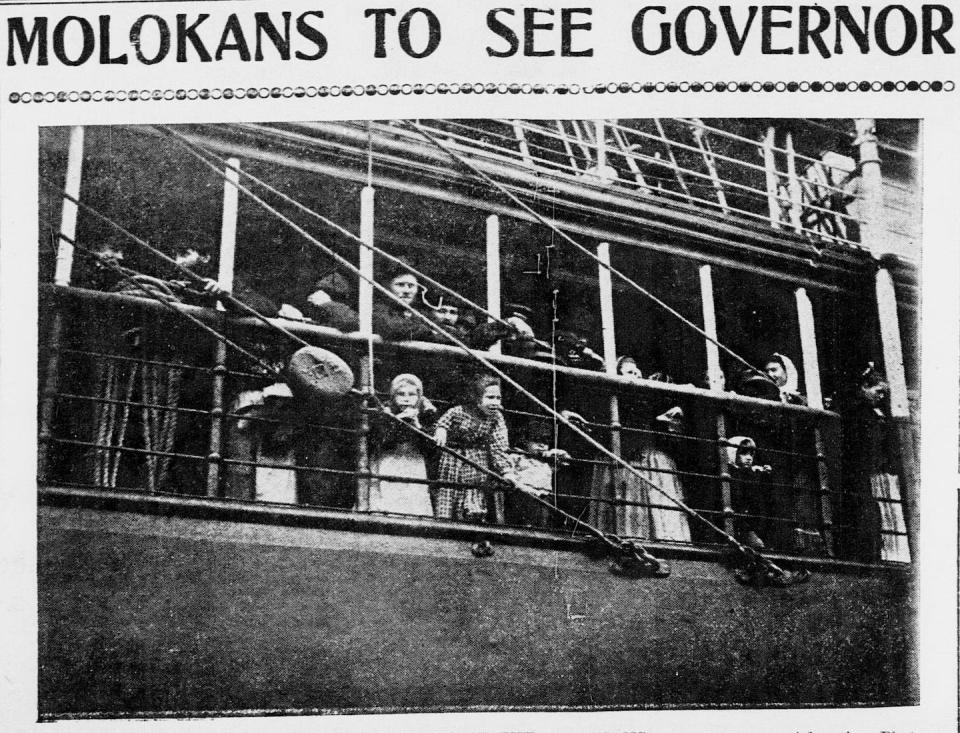

On Feb. 19, 1906, the mail steamer China pulled into the harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii. It had made the voyage from San Pedro, California, many times before, but this trip made front-page news. Local newspapers heralded the arrival of “one hundred and ten white men, women and children, the vanguard of what promises to be an influx of settlers for the Hawaiian Islands.”

A reporter from the Hawaiian Gazette recorded that they “looked to be a healthy, moral, God-fearing people.” By contrast, in 1856, some of the first Chinese contract laborers to work in Hawaii had been described as a “turbulent, stubborn, reckless class” in need of “influences tending to their improvement and conversion to Christianity” so that there might be “a blessing in store for the Chinese in the Sandwich islands,” a former name for Hawaii.

These white Christians were originally from central southern Russia and were part of a decadelong effort by the wealthy white men who owned Hawaii’s sugar plantations to find laborers who would work hard for little money. But as I have learned during my research into Russian migration to the U.S. in the early 20th century, their racial background was key to their arrival in Hawaii: They were white immigrants whom the supporters could liken to American Colonial-era settlers and those expanding west across the Great Plains.

Shifting power in the islands

Since the 1830s, white planters had run massive sugar plantations on the Hawaiian Islands. At first they employed Native Hawaiians. However, the demand for labor grew fast, and as some of the Native population died from European-introduced diseases, there were not enough workers for the industry. In addition, Hawaiians began to organize against meager pay and harsh working conditions as early as 1841. Faced with a possibility of large-scale unrest, the planters started to recruit contract laborers from Asia in the thousands, especially from China.

White elites, like those who overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, wanted Hawaii to eventually become a state. But opponents, like Humphrey Desmond, editor of the Catholic Citizen newspaper, feared that the Asians living there would become U.S. citizens and “dilute the citizenship” of the rest of the white-dominated U.S.

Since the 1880s, Hawaiian elites had tried bringing in workers from Portugal and Norway. They received much higher wages than the Asian laborers and were promoted to skilled occupations faster. A few white farmers also made it on their own to Hawaii, but most of them quickly gave up, their efforts defeated by the harsh tropical climate.

In 1898, the U.S. agreed to annex Hawaii, whose population was just over one-fifth European or American in ethnic background. But that meant the plantations could no longer import Asian workers. They were banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which now applied to Hawaii as a U.S. territory.

In addition, the planters now came under pressure from the growing power of the Asian workers already in the islands. In 1904 and 1905, Japanese laborers led strikes on several plantations across Hawaii, in some cases winning increased pay and other concessions such as firing of negligent overseers.

Enter the Russians.

Moving from the Caucasus

The new arrivals to Hawaii were known as Molokans. A Christian group that had emerged in the 18th century in central southern Russia, they rejected the teachings of the Orthodox Church, which was closely tied to the Russian government.

Starting in the 1830s, they were exiled to the Caucasus region, where Russia had been expanding its empire through conquest. Though they were considered dangerous heretics in Russia itself, in the Muslim-majority borderlands they became indispensable allies of the czar’s government.

Their rejection of alcohol, their strong work ethic and their considerable skill as farmers won the admiration of officials, travelers and scholars. But in the 1880s they were subjected to a military draft for the first time. They objected and in 1900 began a campaign to leave for North America – where, again, they became viewed as ideal settlers, once they started arriving in 1904-1905. The Molokans found a temporary home in Los Angeles.

But then, as I have learned by studying contemporary press accounts and primary sources from the Hawaii State Archives, they caught the attention of the Hawaiian planters.

One of their champions, Peter Demens, a California lumber merchant with Russian roots, described their life in the Caucasus to Hawaiian planters and media audiences as one of unending triumph of industry over nature: “In every place they had to do the work of primitive pioneers; to acclimatize themselves, to acquire the knowledge of local conditions, of local customs, usages, and agricultural methods. From the fertile black earth Steppes of central Russia they were moved into the dry, salty deserts of Crimea, which they quickly transformed into blooming gardens.”

Comparing them to European settlers in early America, Demens further highlighted their moral qualities, such as prohibitions on liquor, tobacco and divorce. He exhorted them as “the only part of the masses who know how to think and who do think.”

In January 1906, the archives reveal, the territorial government and the Molokan leaders signed a land deal. It allowed the Molokans to come to Hawaii to work on a plantation in a land subdivision called Kapa'a on the island of Kauai, learning to cultivate sugar cane and bringing their relatives to join them. When the current plantation company’s lease expired in 1907, the deal pledged that the Molokans could take over, not as wage laborers but as settlers with their own lease rights to 5,000 acres on which to live and work.

Starting to work the land

Within a few hours of landing in Honolulu in February 1906, the advance party of 39 families of Molokan settlers set out for Kauai. Once there, they began building houses. The archives show the manager of the Kapa'a plantation was hopeful, calling their effort “a good augury.”

But once they began to learn to farm sugar cane, trouble followed. The hundreds of longtime Japanese, Hawaiian and Portuguese employees were angry that these strangers, fresh off the boat, were in line to receive a lease over the whole plantation. The longtime workers began to find employment elsewhere, leaving the plantation short of labor.

For the Japanese workers, in particular, being displaced by Russians stung: They had won the Russo-Japanese War just months before. Some Japanese workers refused to work with the Russians, citing the recent conflict as the reason in conversations with the plantation manager. Others reported being the objects of Russian aggression, even saying they had been told, “You Japs drove us out of Manchuria, but we will now drive you out of Kapa’a.”

As indicated by plantation manager George Fairchild’s letters to the settlement’s chief supporter, James B. Castle, the Russian settlers then started to act as if they already owned the lease to the Kapa’a lands. They even told other laborers that the other laborers would soon be working for the Russians and tried to sublease local rice paddies to small farmers.

Making matters worse, the Molokans were used to the cool, arid mountains of the Caucasus, not the hot, humid slopes of Hawaii. Archival records show they also resented the strict labor discipline the sugar cane plantation managers required and refused to work more than 10 hours a day, earning derision from the locals, who were accustomed to 12-to-14-hour days. And they tried to plan for their eventual takeover of the lease, proposing to the manager that each family work a separate section of cane.

A short-lived effort

Having hoped for a peaceful and prosperous settlement, the Molokans faced open resentment by other plantation workers, who likely feared being displaced as more Molokans arrived, and constant complaints from managers about the quality of their work.

Most of them left Kauai, and even Hawaii altogether, by early July 1906 – less than six months after their much-heralded arrival. The failed experiment laid bare the flawed concept of Americanizing the islands by increasing the white population. While other labor migrants, such as Portuguese, earned a better reputation with the planters and remained in numbers sufficient to establish a significant cultural presence in the islands, the demographic makeup of the islands would change little in the coming decades.

The plantations went back to relying on the labor of people already in Hawaii, as well as people arriving from the Philippines, which had recently become a U.S. colony.

But for a brief moment, thanks to widely shared notions of white supremacy and colonization as a positive force, even people as different as the Russian Molokans could be likened to the Pilgrim fathers of American settler myth: people who simply by virtue of their looks and background symbolized civilization, progress and a powerful connection with an imagined past.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts. Try our free newsletters.

It was written by: Stepan Serdiukov, Indiana University.

Read more:

Patsy Takemoto Mink blazed the trail for Kamala Harris – not famous white woman Susan B. Anthony

Racists in Congress fought statehood for Hawaii, but lost that battle 60 years ago

Stepan Serdiukov does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

money

money