What's going on with Iran's raging protests?

In September, a young woman named Mahsa Amini died while detained by the Iranian morality police after being arrested for improperly wearing her head scarf, or hijab. Her death sparked major protests in the capital city of Tehran, as well as cities around the country, including Kerman, Mashhad, and Shiraz, driven by people sharing videos and photos of the incident, the subsequent protests, and the predictable crackdown by security forces as well as plainclothes heavies known as Basij. While the protesters have made significant strides in shining a light on the injustices within Iran, the nation's top officials have continued to come down hard on dissidence. Here's everything you need to know:

What are the protests about?

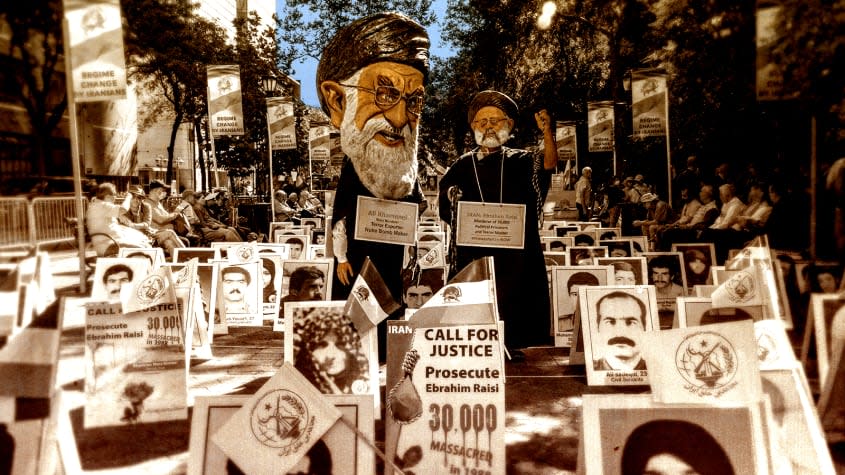

The suspicious death of Amini, 22, is the clear proximate cause of the protests. In classic authoritarian fashion, authorities tried to blame her demise on a heart attack, with state media releasing videos purporting to show her collapsing while in the custody of the morality police. But photos from the hospital show the young woman bleeding from her ear, and other officials have argued she died from severe head trauma. The immediate outbreak of protests, including women burning their hijabs and crowds chanting "death to the dictator" — an almost unimaginable provocation in authoritarian Iran — led the country's hardliner president, Ebrahim Raisi, to apologize directly to Amini's grieving family. "Your daughter and all Iranian girls are my own children, and my feeling about this incident is like losing one of my own dear ones," Raisi told the family, promising an investigation into the incident. His words placated no one.

The sequence of events is reminiscent of the 2010 killing of a young Egyptian man named Khaled Said, or the event that set off the Arab Spring in 2010 — the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia after police prevented him from selling fruits and vegetables without a permit. Outrage and revulsion at a single arbitrary exercise of authoritarian violence quickly spiraled into a broader spasm of frustration with the regime itself. Bloated security sectors are known for routinely abusing the citizenry, who have few meaningful civil rights or civil liberties to use against the state. And Iran's repressive policies against women are a longstanding source of tension, particularly in major cities where people tend to be more liberal and less approving of the Islamic Republic's ideological foundations.

Unlike the mammoth protest movement that emerged in the wake of the disputed 2009 presidential election, the Green Movement, protesters are explicitly calling for an end to the regime. Just as Tunisians, Egyptians, Syrians, and others weary of oppression across the Arab world chanted, "The people demand the fall of the regime," Iranians are suddenly mounting a head-on challenge to the country's theocracy in the streets. The eyes of the world have now been turned to the protesters, the majority of whom are college-age women like Amini. The issue particularly made waves at the 2022 FIFA World Cup, where the Iranian national soccer team attempted a silent protest in solidarity with the protesters before reportedly being threatened by the government. The team's loss to the United States was reportedly even celebrated by many protesters across Iran, calling the defeat a morale blow to the authoritarian regime.

How resilient is Iranian authoritarianism?

Iran's dictatorship is now older than most people alive in the country, and after more than 43 years, it is clear that the regime will not be dislodged bloodlessly. Iran's system of government, which features an elected legislature and president (albeit with severe restrictions on who may run), successfully co-opts legions of potential dissidents into the system itself, all while preserving its darkly ingenious, circular structure of authority. However, all roads lead back to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his hand-picked Guardian Council. Elected officials operate under the illusion of autonomy, which can be withdrawn at any moment when policy runs afoul of official regime dictate. Even the president, despite being Iran's official head of government, is mostly subservient to the Supreme Leader, who has the final authority on numerous government policies. Khamenei, in power since 1989, has praised his country's authoritarian nature, as well as the paramilitary groups working to quash the protesters.

Yet in recent years this structure has been insufficient to head off mass protests. Successful authoritarian rule relies on a mixture of threatened repression, prosperity, and stability. But despite strong economic growth this year, Iran's isolation from the global economy still has left young people in particular with diminished life prospects. The World Bank estimates that almost a third of the country's young people aren't working, in school, or in another form of employment training. That has led to waves of popular unrest that seem to be arriving more and more frequently. The regime has been forced to rely on blunt coercion, a tactic that alienates the population the more frequently it is deployed. After the 2009 protests, thousands of Green Movement leaders and activists were arrested, and dissident leaders were given show trials. Yet the government carefully calibrated the violence, as Borzou Daragahi writes, consequently "avoiding too much international attention and the all-out wrath of the public."

What's the bottom line?

A gambler would bet on the regime weathering these protests with a combination of repression and concessions. That's what has happened in every past street mobilization — the well-funded and gargantuan security forces restore order and protesters return to their homes with little to show for their efforts. But because the regime has clamped down on Internet access and social media sites, and because journalists cannot operate freely in Iran, it is difficult to know exactly how large the protests have gotten. Political scientists have found that in order for a street uprising to succeed, the dissidents must somehow splinter regime elites, convincing security forces not to unleash violence to maintain the status quo and forcing a negotiated transition process on reluctant rulers. There is no evidence yet that this is happening yet in Iran, where the country's elite Revolutionary Guard Corps wields extraordinary political and economic power.

One last problem for authorities in Tehran: Amini was from Iranian Kurdistan, where protests are fierce. At least 98 protesters have been killed in the region already. The country's Kurdish minority has long chafed at rule from Tehran, and this incident could be the trigger for a broader rebellion against the regime, one that has not just ideological features but ethnoreligious ones as well. And while Khamenei and his enforcers might be able to fight a one-front battle against defenseless protesters, adding in a breakaway region could complicate the government's efforts to suppress the uprising.

With all of these factors combined, there may be signs that the dissidence across Iran is beginning to slowly work. Reports have now emerged that the country has shut down its morality police, though this is something the Iranian government itself has denied. However, officials did say they would potentially be re-evaluating the country's hijab law, perhaps paving the way for the beginning of some changes in a nation that appears to be near a watershed moment.

Dec. 5, 2022: This article has been updated with additional information throughout.

You may also like

How low will gas prices go this winter? 3 analyst predictions.

439 Texas churches split from United Methodist Church as slow-motion schism continues

money

money