After valley fever rips through Arizona breeding colony, questions are raised about monkey research

The largest pigtailed macaque breeding facility in America — a key outpost connected to the University of Washington that has contributed research into HIV, Ebola, Zika, COVID-19 and other diseases — has been relying on a pool of monkeys tainted by infectious disease, a USA TODAY Network investigation has found.

Exposure to Valley fever, a common flu-like illness caused by fungus from the soil in the desert around Phoenix, could mean conclusions drawn about treatments for human diseases have been flawed.

At least two University of Washington reports say that monkeys infected with Valley fever threaten the reliability of research, and one of those studies states that pigtailed macaques with a history of Valley fever should not be used in HIV research, which makes up 35% to 50% of all studies involving the more than 1,000 monkeys housed in the primate center’s Arizona and Washington facilities.

At least 47 monkeys have died from with the illness over the past eight years, UW said in a statement.

The problem with Valley fever is that it can remain encased in the lungs, and even though a monkey may show no symptoms, the illness can recur when its immune system is suppressed during HIV research trials.

That’s what a team of University of Washington researchers discovered during a 2020 study of macaques that were experimentally infected with simian immunodeficiency virus, a retrovirus similar to HIV that infects African non-human primates.

A macaque from the Arizona breeding colony previously contracted Valley fever, but it was controlled through anti-fungal treatment. When the macaque's immune system was suppressed by SIV during the research, its Valley fever came back. Researchers could not stabilize the monkey’s breathing and it had to be put down.

The study’s conclusion: “macaques with a history of coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) should be excluded from enrollment in HIV studies.”

A retired certified laboratory animal veterinarian who reviewed necropsies of more than 35 macaques for the USA TODAY Network went even further by suggesting that every animal at the Arizona facility has had Valley fever, even if the monkeys never tested positive for the disease.

The veterinarian requested anonymity over concerns of retribution from the veterinary community and fears that being identified could cause former colleagues to come under scrutiny.

The USA TODAY Network contacted 10 veterinary experts and organizations in the United States and the United Kingdom to review necropsies and other records. That included Arizona’s two veterinary schools, the University of Arizona and Midwestern University in Glendale. All either declined or didn’t respond.

The retired veterinarian said a large number of the necropsies that were reviewed either contained suspicions of Valley fever or pointed to valley fever as the cause of death. The veterinarian called that “extremely surprising.”

“It’s unbelievably uncommon to get one disease repeating over and over again,” the veterinarian said of the necropsies. “I think every single monkey there has been exposed and to some degree has had Valley fever.”

In a written response to questions from the USA TODAY Network, the University of Washington said it neither “agrees or disagrees with this assertion,” adding that in desert communities a significant number of humans and animals would show antibodies for Valley fever at some point in their lives.

The university has already taken steps to get Valley fever under control. The macaques now spend more time indoors where HEPA air filtration systems have been installed. Their outdoor access has been restricted during high winds, and the facility prescribes drugs for at least six months and sometimes longer than two years to suppress infections.

“Losses from Valley fever have decreased from a high of 18 in 2014 … to 1 in 2018,” according to a 2020 UW grant application.

The university also insists that Valley fever does not represent a threat to scientific research. In fact, it says macaques' complex immune system and history of disease makes the monkeys valuable for comparison to humans.

“Part of what makes a (non-human primate) a valuable animal model is that it responds similarly to humans. A naive immune system that has not seen any pathogens does not model the human condition,” the UW statement says.

But Thomas Hartung, the director of the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing at Johns Hopkins University, said the disease histories of nonhuman primates actually makes them more difficult to experiment on.

With mice, researchers can standardize their breeding and keep them in tiny cages to make sure they don’t come into contact with disease. Not so with animals like monkeys because they breed slowly and have disease histories.

“These nonhuman primates are much more diverse and diversity is an enemy of results — of clear cut results — because then you need many more animals to compensate for the diversity to get a good result,” Hartung said. “This is something you cannot afford with these precious animals. They are expensive.”

But while Valley fever is one of the most pressing problems facing the Washington National Primate Research Center and its Arizona breeding facility, it is by no means the only one.

The USA TODAY Network spent seven months reading through hundreds of pages of lawsuits, necropsies, grant applications, research papers, financial reports and environmental studies. It interviewed veterinarians, animal rights and environmental experts, university professors, researchers, and others familiar with UW’s non-human primate operations in both Mesa and Seattle.

Among the findings:

Environmental studies show the monkeys at the Arizona breeding facility are drinking water that’s tainted with perchlorate, a contaminant from rocket fuel leaked from a nearby defense contractor. Perchlorate, which has been found to affect the thyroid, has the potential to harm groups most crucial to the breeding colony — infants and pregnant and nursing females. Despite recommendations in 2016 that a filtration system be installed, the primate center has taken no such precaution saying a filtration system was not needed.

The primate’s center long-term financial situation is in disarray according to federal reports. Staff turnover has been high. Key researchers have left and leadership positions have remained open until just recently. Morale, while improving, remains low as staff has reeled from years of poor decision making and an embarrassing public sexual harassment scandal.

The primate center has violated rules on importing exotic animals into the State of Washington and has been cited for failing to notify the Washington Department of Agriculture that the monkeys were infected with Valley fever — a requirement designed to prevent the spread of disease.

The center also has run afoul of the federal Animal Welfare Act for killing and injuring at least five monkeys. One died of thirst because the water to its cage was disconnected. Another died because scientists did not have it fast properly before surgery. A third hung itself on a chain attached to its cage. These incidents are similar to what led Harvard University to close its New England Primate Research Facility in 2015.

This is not the first time the Washington National Primate Research Center has faced an existential crisis. In the 1990s, its research program, which is one of seven in the country, also came under siege for its inhumane and careless practices.

In written responses to questions from the USA TODAY Network, UW insisted that it treats animals responsibly and “is very transparent about the work it does, including when things go wrong.”

“Any adverse event that occurs at our facility whether in Seattle or Arizona is devastating especially if it results in the death of an animal,” UW said.

The university added that monkeys are not exposed to hazardous levels of perchlorate and the water in Arizona is safe to drink. It also pointed to recent annual reports from the National Scientific Advisory Board showing improvements in the primate center’s finances and employee morale.

A press release from early September revealed that it has hired a new director after an 18 month vacancy. Michele A. Basso is discussing plans to recruit new investigators and core staff particularly in the field of HIV and the intersection of neuroscience and infectious disease, the statement said.

But the USA TODAY Network learned that Basso, a psychiatry, biobehavioral sciences and neurobiology professor, was criticized by veterinarians in 2009 at the University of Wisconsin for improper care of monkeys. Her research, which involves inserting electrodes into monkey brains, was temporarily suspended.

Basso blamed much of her problems on the veterinary staff and filed a grievance with the university’s faculty committee, which ultimately found that the university had violated Basso’s right to due process and the animal care committee overstepped its authority in suspending her research.

Basso said in a statement to the USA TODAY Network that she was exonerated of all charges of wrongdoing in Wisconsin, adding "I consider it a privilege to work with these animals and one that I do not take lightly."

She said she is eager to work with the University of Washington to ensure the financial stability of the primate center.

"I am looking forward to building education and community outreach programs that provide members of the public with knowledge of our contributions and also about the critical role that animals and particularly non-human primates, play in biomedical advances," Basso said.

A jungle creature living in the desert

Pigtailed macaques abound in the steamy jungles and swamps of Southeast Asia. They live in large, tight-knit social groups that can number from several dozen to as many as 50, and they love to be around water.

Their native habitat, therefore, is a far cry from the parched desert north of Mesa where the nation’s largest pigtailed macaque breeding facility is located near a gravel pit and a defense contractor that has fouled the environment over the decades.

The monkeys are housed in pens that give them both indoor and outdoor access, which is considered healthy for their mental and physical welfare. But being outside brings them in contact with the biggest scourge of the Arizona environment: Valley fever.

Valley fever is a fungus that lives in the Southwest United States, parts of Latin America and now south central Washington State. Spores circulate in the air after soil is disturbed by wind or other forces. People and animals catch it by inhaling the spores.

Dogs and humans typically suffer only minor symptoms such as fatigue, coughing and fever. One in 100 people who get Valley fever have it travel to their blood, bones and central nervous system, according to the CDC.

Pigtailed macaques aren’t as lucky.

They are “highly susceptible” to Valley fever spreading from an infection in the lungs to disease in the rest of the body, according to an internal report by former UW veterinarian Lee Chichester. Valley fever spreads and disseminates, gaining access to the bloodstream and the macaques' bones, central nervous system and liver.

Severe clinical signs from Valley fever that were seen at the facilities include meningitis, bone lesions and draining tracts from the liver, lymph nodes and bones, Chichester’s report says. Euthanasia “must be strongly considered in many cases” because pigtailed macaques have “a more severe disease progression than is seen in other species.”

Having to put down monkeys suffering from valley fever has led to high mortality rates at the monkey breeding facility, exceeding UW’s goal of no more than 10% per year.

In the fourth quarter of 2014, when the facility housed about 350 monkeys, the quarterly annualized mortality rate hit 19% after the facility had to kill 18 monkeys because of Valley fever that year, internal UW documents and grant applications show. The quarterly annualized mortality rate was 15% or more in parts of 2016 and 2017.

For some macaque populations the death rate has been much higher.

For infants, the mortality rate spiked above 35% in parts of 2016, internal documents show, and above 40% in parts of 2018. In the fourth quarter of 2019, the mortality rate for infants was 17%.

Despite UW’s own internal documents showing those death rates, written responses from the Washington National Primate Research Center dispute that the Arizona breeding colony ever had a mortality rate approaching 20%. UW Spokeswoman Tina Mankowski said the highest annual mortality rate was 9%. Later, she came back and said it was 10.5%

UW's statement said that annual numbers can vary "depending on whether you add four consecutive quarters together or multiply the number for a single quarter by 4," which is what the quarterly annualized rate is.

"This graph is an internal document meant for examining trends and identifying areas for improvement; it is not providing annual data," the statement said.

In addition to sickening and killing the monkeys, Valley fever has the potential to “confound research” — to bias or potentially ruin the conclusions — according to Chichester’s report. That’s because of the risk that Valley fever can re-emerge after a period of seemingly being cured.

That’s what a team of University of Washington scientists working for the National Primate Research Center in Seattle discovered while doing a study evaluating a novel hepatitis B virus vaccine for people living with HIV in 2020.

Two years prior to being enrolled in the study, a macaque was coughing while at UW’s Arizona facility and later tested positive for Valley fever. It was treated with an anti-fungal agent and tested negative three times over the course of a year. Three months before the study the macaque was moved to Seattle and housed strictly indoors.

During the research, the monkey was infected with simian immunodeficiency virus — similar to HIV in humans — then given combination antiretroviral therapy similar to the medicines a person living with HIV would receive.

The monkey’s Valley fever became detectable prior to discontinuation of the antiretroviral therapy. The monkey became symptomatic two weeks after the treatment was finished. It had difficulty breathing, “marked by open mouth breathing and audible wheezing,” the study said.

The researchers sedated and intubated the monkey, but couldn’t stabilize its breathing. The macaque had to be put down.

“To our knowledge this is the first case report documenting (the recurrence) of a naturally occurring” Valley fever in a non-human primate enrolled in HIV/AIDS-related research, the study said.

It called for screening nonhuman primates in HIV/AIDS research, when there is potential for fungal exposure, especially those from outdoor colonies where the illness is endemic, such as Arizona.

Nonhuman primates with a history of Valley fever “should be excluded from enrollment” in SIV research “regardless of successful anti-fungal treatment” and negative tests, the study said.

So far, UW and the National Institutes of Health have treated this study as an anomaly — a single case in which Valley fever in a macaque has spoiled the results of HIV research.

UW said it is up to individual researchers to determine whether to exclude monkeys that have previously had Valley fever. It added that the primate center provides a full health history to anyone who buys monkeys for research.

UW said that nine Valley fever positive monkeys have been used in HIV/SIV research in the last two years and “all studies were completed without incident.” The National Institutes of Health, which provides much of the money used by UW to raise the macaques for scientific research, said past studies involving Valley fever positive macaques are sound.

“Even with a low rate of unrecognized (Valley fever) in macaques in past studies, results of those studies remain valid due to the way research studies are designed, with treatment arms being compared to control arms and replication, randomization, and blinding being applied to all study groups,” the NIH said in a statement.

Still, there’s plenty of evidence that Valley fever can affect the monkeys long-term and appear after a period of dormancy.

After PETA filed a complaint in April, UW gave the Washington Department of Agriculture a list of all the monkeys it had imported to the state that have had Valley fever. There were 45 on the list. But Valley fever was not diagnosed in 19 of them until after they had arrived in Seattle.

Since the monkeys are kept indoors and Valley fever isn’t present in Seattle, it means the disease only presented itself after the monkeys left Arizona. The median number of days before the monkeys tested positive after arriving in Washington State was 47.

Three of the monkeys didn’t test positive until more than 15 months after arrival.

Animals are not very good at completely eradicating the infection caused by Valley fever, said Lisa Shubitz, a veterinarian and a research scientist at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence at the University of Arizona.

Although Valley fever may seem like it is gone, Shubitz said, in actuality the immune system has built a wall around it in the lungs and keeps the infection in check. But if the immune system is severely suppressed, Shubitz said Valley fever grows again and can spread throughout the body quickly and become fatal.

“It’s not just that it kills some of their animals, it affects the research they do with them also,” Shubitz said. “It affects their ability to do this immunology research because you're limited in being able to wipe out or suppress that animal’s immune system. You risk having your experiment ruined by having this disease come back.”

Perchlorate in the water

A week after the University of Washington signed a letter of intent to lease the former Mesa-area monkey farm from the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community in May 2011, its new next-door neighbor, Nammo Talley, filed a lawsuit against its insurance companies.

A defense contractor, Nammo had polluted the soil and water on the land just south and east of the sanctuary over decades of manufacturing rocket systems. It wanted the insurers to help pay for the clean up.

The lawsuit explained that part of Nammo’s business involved replacing rocket propellant in aged, and yet to be deployed missiles and rocket motors. It used water to bore out the rocket fuel, then screened and recovered the solid materials and discharged the leftover liquids into unlined evaporation ponds.

Chemicals from those ponds gradually leached into the groundwater, causing an underground plume that has been moving west into the Indian Community towards the primate center. Because of the center’s remote location, the only water source for the monkey colony is groundwater from two wells.

“If you are going to be breeding monkeys for use in biomedical research, the last place you want to be breeding them is where they are exposed to lead and other toxins,” said Lisa Jones-Engel, who served as a senior research scientist at the primate center and a faculty member at UW for 17 years. “They are at the most vulnerable stage as a developing fetus and an infant.”

In 2019, Jones-Engel resigned her position at UW in protest because she believed there was a lack of oversight of UW’s biomedical research program and infectious diseases were compromising the science. She joined People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals as a senior scientific advisor for primate experimentation.

Jones-Engel maintains there was a lack of due diligence on the part of UW prior to signing the lease to the old Monkey Farm. Nammo Talley’s issues were well known.

“Somebody somewhere wasn’t doing their job,” she said.

Perchlorate primarily affects humans and non-human primates by disrupting the thyroid’s ability to produce hormones needed for normal growth and development, according to the EPA.

“It’s especially worrying for the developing fetus and young child because thyroid hormones support brain development,” said Frank von Hippel, a perchlorate expert and professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Arizona.

It is unclear if perchlorate is having any effect on the macaques at the primate center. But studies have shown that exposure to perchlorate can cause hair loss in mice. And macaques at the facility are having problems with hair loss.

Primate center researchers studied hair loss in its Arizona macaques in 2019. They wanted to determine whether the hair loss could be linked to a reduction in outdoor activity, pregnancy or because of the antifungal agent given to the macaques to combat Valley fever. Results were mixed and linked some hair loss to the antifungal agent, age and the amount of space the monkeys had to roam. Researchers, however, did not test to see whether hair loss could have been caused by perchlorate in the water.

“It is well documented that alopecia is common among non-human primates,” a statement from UW said. “Since they have not been exposed to perchlorates, that is not a factor with regards to the alopecia.”

In August 2014, water from the well the monkeys drink from tested positive for perchlorate, registering 2.7 parts per billion. That amount exceeded Massachusetts' 2 ppb perchlorate drinking water standard for humans, which is the most stringent in the nation. There is no Arizona drinking water standard for perchlorate.

A consultant for Nammo developed a standard for how much perchlorate the pigtailed macaques could tolerate drinking from the primate facility’s main well, putting it at 6.4 parts per billion because of the macaques lower body weight and higher consumption of water.

Nammo and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality agreed upon a contingency plan where a treatment system would be procured and installed within 120 days if a test came back higher than 3.2 parts per billion.

In February 2016, a representative from Nammo sent an email with tests that showed perchlorate at 9.5 parts per billion and requested an urgent meeting. There was a conference call between all the parties, according to an email from ADEQ’s Richard Olm.

“The ion exchange system is being procured and will be installed within 120 days,” Olm’s email said. “In the interim, potable water from a (Nammo) production well will be trucked to the primate facility at the volume required, which may be as much as 4,000 (gallons per day).”

But nothing ever happened.

ADEQ and EPA officials said new samples came back showing no trace of perchlorate and concluded the previous test was either an error in analysis or that the sample was somehow contaminated.

Since then, the wells have periodically tested positive for perchlorate at levels below those that would trigger the treatment system. The wells are tested three to four times a year.

That’s not nearly enough, von Hippel said. The levels of perchlorate that the tests have found are reassuring because they are below most of the most stringent levels of perchlorate for humans. But the amount that the water is being tested is not reassuring because perchlorate is so water soluble it can move around quickly and amounts can ebb and flow depending on how much it rains.

An ion exchange treatment system similar to the one proposed by ADEQ and the EPA would cost about $100,000 to install and with minimal costs to operate, said Bryan Woodruff, business development executive with Samco Technologies.

The University of Washington said Nammo Defense Systems would have to pay for the treatment system, but “to date there has not been a need to install the system because there has never been a perchlorate level that would trigger such an installation.”

Carole Thompson, communications manager for Nammo Defense Systems, agreed the system was not needed.

A system in turmoil

The 2018 review of the Washington National Primate Research Center by the National Scientific Advisory Board — a report that is required to receive funding from the National Institutes of Health — didn’t pull any punches.

It called out the center’s ineffective leadership, its crumbling finances, high turnover and low staff morale.

While it praised the science coming from the primate center, the report said the financial issues were formidable and that some “border on insurmountable.”

The National Scientific Advisory Board said there was little the center could do to address these issues. That’s because the grants that fund most of its research are determined by the National Institutes of Health and they have remained flat or declined in recent years. At the same time, costs have been rising and the primate center is locked into “unfavorable lease agreements.”

The National Scientific Advisory Board went on to berate the primate center about the deterioration of its HIV/AIDS research division and about inadequate staffing at the primate center in Seattle and at the Arizona breeding facility. It also mentioned staff changes caused by a sexual harassment scandal that rocked the reputation of the university and its primate research programs.

The scandal centered around Michael Katze, a star researcher and head of systems biology division. An investigation found he had sexually harassed at least two women over the course of several years.

One woman had a “quid-pro-quo” sexual relationship where Katze paid her thousands of dollars more than she could get elsewhere and gave her cash and gifts like shoes or vacations in exchange for oral sex, the investigation said. Katze was also found to have sexually harassed another employee by “touching her buttocks and breasts” and exposing his penis on “four or five occasions.”

Katze, who became the subject of a BuzzFeed expose, also watched pornography on his work computer despite previous warnings, according to the investigation. Employees described his behavior as “cruel, crude and characterized by frequent profanity.”

The issues identified in the NSAB report led the National Institutes of Health to restrict UW from spending grant funds from the UW’s largest primate grant.

University of Washington spokeswoman Tina Mankowski pointed to more recent National Scientific Advisory Board reports that said appointment of the primate center interim director Sally Thompson-Iritani had stabilized the primate center resulting in improved employee morale.

Jones-Engel, who left UW in protest in 2019, said it was the severity of the 2018 report that first kicked off her concerns about the administration’s lack of oversight.

“It was that 2018 report that started everything,” she said. “This was what was surprising at how sharp this review was. It was basically saying ... ‘you are a mess.’”

Breaking state and federal rules

Many of the world's most devastating viruses have jumped from animals to humans.

COVID-19, the pandemic currently ravaging the planet, likely jumped from a bat to another species and then to humans.

In turn, one of the world’s most terrifying diseases, the Ebola virus, jumps from bats or non-human primates to infect humans. And a virus that has a bigger impact than almost any other — HIV/AIDS — has killed more than 36 million people after humans caught the disease from the nonhuman primates they were hunting for meat.

That’s why states have reportable disease requirements for exotic animals brought into their jurisdictions.

But the University of Washington has not been following those laws and rules in Washington state for much of the past seven years. Since 2016, it has imported 283 monkeys into Washington state in six shipments, violating state law and regulations.

UW failed to notify the Washington Department of Agriculture that any of the monkeys were infected with Valley fever — which is on the state’s list of reportable diseases and animals with it must be reported to the Washington state veterinarians office.

In five of the six shipments, UW failed to provide certificates of veterinary inspection for the monkeys, which is a requirement for exotic animals. In all six shipments, it failed to obtain entry permits for the monkeys, another requirement.

“What happened was that they changed veterinarians at their Arizona facility,” said then-Washington state veterinarian Brian Joseph. “Their old veterinarian failed to fully train and inform their replacement. … They were ignorant of our regulations.”

In its response, UW blamed the previous veterinarian for not conveying information to the new veterinarian that permits were needed. Charlotte Hotchkiss, the acting associate director of primate resources, said they didn't realize that a previous veterinary form was no longer approved as of 2018.

UW said it didn’t report the Valley fever because it is not contagious between animals or between animals and humans, adding it didn’t realize Valley fever was on the list of diseases reportable to the state.

Jones-Engel said it’s fairly astonishing that a national primate research center doesn’t know the laws for importing exotic animals in its home state.

“I’m trying to wrap my brain around how a national research center would have failed to follow these most basic state laws, which are designed to protect public health,” she said. “That's why we have those laws.”

Jones-Engel said PETA also has found little evidence that UW has been getting proper permits in other states, including Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, and New York.

Although Valley fever itself cannot be transmitted from monkeys to humans, Valley fever can weaken the monkey’s immune system and make it more vulnerable to diseases that are transmissible between animals that could also pass onto humans, Jones-Engel said.

In addition to running afoul of state laws, the Washington National Primate Research Center has violated animal welfare rules set by the National Institute of Health’s Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Some of the violations are similar to incidents that led Harvard University to close its New England Primate Research Facility in 2015.

The Washington National Primate Research Center has had five monkey deaths because of poor care or improper oversight in Washington and Arizona since 2017.

In March 2019, a macaque that was scheduled for surgery had not fasted properly overnight due to a miscommunication. Staff delayed the surgery for an hour, but then went ahead. The monkey went into respiratory arrest, throwing up and then breathing in its vomit. Medical staff stabilized the animal but it later died.

At the Arizona facility in November 2018, staff members found a two-year-old female pigtailed macaque with its arm caught in the metal mesh of its cage. The animal was sedated and the mesh was cut to free it, according to a report made to the Office or Laboratory Animal Welfare. The animal fractured its arm at the growth plate and couldn’t move its fingers on the affected side and was ultimately put down.

In April 2018, a monkey accidentally strangled itself on a foraging device that had not been properly installed, a report from the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare said. The University said the device had been modified to fit the space.

In January 2017, workers forgot to connect a water line to a monkey’s cage. The 8 year-old macaque was found lethargic and severely dehydrated. It died during treatment and necropsy findings pointed to a cause of death that was consistent with a lack of water for 48 to 72 hours.

Just three months later, a monkey died while under anesthesia related to an experimental magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) procedure. Staff was found to have inadequate anesthetic monitoring records for the procedure where the animal died.

There were more deaths too. Three baby macaques were killed when attacked by older macaques in three separate incidents in 2014, according to USDA records.

“For at least 13 years, systemic and egregious deficiencies have persisted in the care and treatment of animals in UW’s laboratories,” PETA wrote in a letter to the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare in 2019. “Federal authorities have documented habitual neglect of animals, routine lapses in veterinary care, and intolerable suffering of animals in the school’s laboratories.”

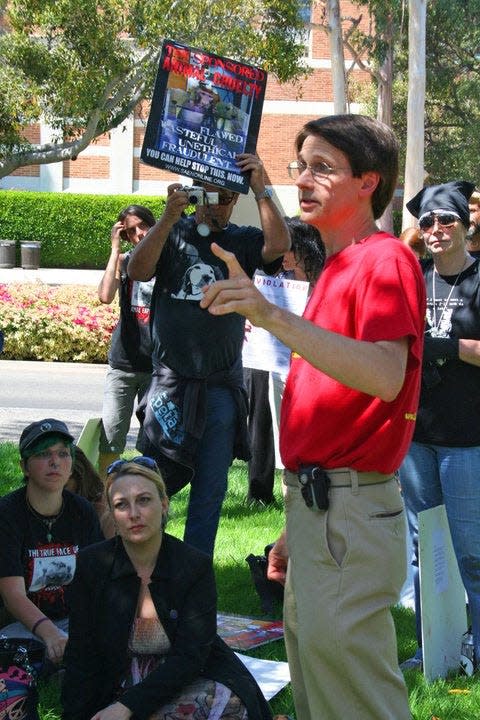

Michael Budkie, co-founder of Stop Animal Exploitation Now, filed a complaint in mid-August with Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) — the same group that put Harvard’s primate center on probation nearly 10 years ago.

The complaint calls for an independent investigation into the incidents and the revocation of the University of Washington’s accreditation.

“In what laboratory is giving food and/or water optional?” Budkie asks in the complaint. “How is it that (the) UW lab can’t keep monkeys alive through surgery?”

UW said in a statement that it is devastated when adverse events such as these occur.

“The staff at WaNPRC who are responsible for the care of the animals on a daily basis have dedicated their careers to ensuring that animals that are used in scientific research receive optimal care at all times,” the university said. “This includes the veterinary staff, behavior management staff and the husbandry staff – when an adverse event occurs everyone is impacted.”

Budkie countered that UW has demonstrated a long-term problem with complying with the Animal Welfare Act.

But even putting aside the welfare of the animals, he said the animals' exposure to Valley fever and perchlorate is compromising the research because the animals' health and immune system are compromised before the research even begins. And in many cases the research the macaques are used for involves infections disease, particularly HIV/AIDS.

He said there is no way that researchers could use pigtailed macaques from UW’s Mesa-area facility and “not have the research somewhat corrupted by the condition of the animals.”

“It’s really making the monkeys into extremely poor research subjects,” Budkie said. “Having a facility in this location is just pointless for them. It’s like taking the monkeys and throwing them away.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Widespread sickness in Arizona monkey colony could bias research

money

money