President Trump's payroll executive order could leave Americans with 'substantial tax liability'

Americans could owe a huge tax bill if President Donald Trump’s executive order on payroll tax deferrals is implemented, according to a letter from 32 trade organizations representing various sectors and the U.S Chamber of Commerce.

The president’s action on Aug. 9 also presents numerous other challenges for employers and payroll processors, according to experts and business groups.

“Under current law, the [executive order] creates a substantial tax liability for employees at the end of the deferral period,” the Aug. 18 letter stated. “Without congressional action to forgive this liability, it threatens to impose serious hardships on employees who will face a large tax bill as a result of deferral.”

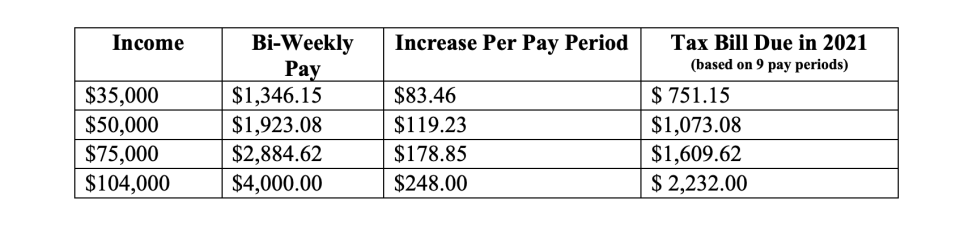

The letter also included a chart demonstrating what workers would owe next year when they file their taxes if the deferral is not forgiven by Congress. The undersigned organizations urged the administration and Congress to come together to provide much-needed tax relief for families without the uncertainty associated with the recent payroll tax Executive Order (EO).

The letter followed another letter with similar warnings that was sent from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

“Not only is the payroll [executive order] surrounded by uncertainty as to its application and implementation, it creates a substantial tax liability for employees at the end of the deferral period,” the Aug. 12 letter stated. “As current law provides, this is a deferral of tax due, and without congressional action to forgive the payroll tax, it threatens to impose serious hardships on employees who will face a large tax bill at the end of the deferral period.”

The concerns add to the mounting confusion surrounding the executive orders and memorandums to address pressing economic problems amid stalled congressional negotiations over another stimulus package during the pandemic.

‘Employees will ask: ‘Do I want to do this?’

The executive order directs the Treasury secretary to defer the 6.2% payroll tax that employees pay each pay period into the old-age, survivors, and disability insurance fund, starting Sept. 1 and ending Dec. 31. This tax funds the system that pays out benefits to Social Security recipients.

But the order only allows for a deferral, meaning those taxes would eventually have to be paid to the federal government, likely at tax time next year, unless Congress passes legislation that forgives these deferrals, according to Pete Isberg, vice president of government relations for ADP, a payroll processing firm.

“This doesn’t excuse the tax,” Isberg told Yahoo Money. “Employees will ask: ‘Do I want to do this? If I don’t withhold the taxes, am I still liable?’”

Employers also may be reluctant to let workers defer, because companies are legally responsible for withholding those payroll taxes, according to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Until employers get more detailed guidance, they would rather not run afoul of IRS requirements, Isberg said.

‘Uncertainty raised by these issues’

Employers are also confused on how to implement the deferral in the first place, the Chamber’s letter last week and a new statement from the National Payroll Reporting Consortium both said. There is no guidance on how employers should treat changing salaries or bonuses, seasonal workers, or employees who quit before the end of the year.

Without guidance — and quickly — implementing these changes into a payroll system could take months from the Sept. 1 start date for some employers who do their own payroll, Isberg said. The Chamber also noted this.

“The uncertainty raised by these issues, as well as myriad other issues not enumerated here, only exacerbates the challenges faced by payroll processors and compliance departments who are already struggling to implement this [executive order] in an extremely short period of time,” the letter said.

The NPRC similarly said that by lacking guidance from the IRS on many open-ended questions on implementation, “not all employers and payrolls systems will be able to make these complex changes by September 1.”

There’s even a question of which workers would qualify, Isberg said.

The executive order said those making less than $4,000 in a bi-weekly period can defer their payroll taxes, which is less than $104,000 a year. But a government release that ADP and others received later said the income maximum was $100,000 a year, which could make a difference in how much a worker can get from the deferral.

For instance, using the $4,000 bi-weekly limit means the maximum deferral for the year is $2,232 based on the nine remaining pay periods from Sept. 1 to the end of the year, Isberg said. But, he added, change the limit to $100,000 a year, and the max deferral could be as much as $6,448 for a theoretical worker who had no job until Sept. 1 and then started one making $100,000 a year.

“If you do the math, you get very different results,” Isberg said. “We’ve asked the IRS and Treasury to clarify how to implement the limit.”

Janna is an editor for Yahoo Money and Cashay. Follow her on Twitter @JannaHerron.

Read more:

The IRS is failing to collect billions in back taxes owed by super rich Americans

How the extended tax deadline affects payments, retirement contributions, and more

Tax expert: Americans who don't file leave ‘billions of dollars’ on the table

Read more personal finance information, news, and tips on Cashay

money

money