'If you think too much, you cry': Nurse shares what it's like to care for the sickest coronavirus patients

WOODLAND PARK, N.J. – Arlene Van Dyk doesn’t know if her patients can hear her. They are unresponsive, sedated into paralysis so that machines can do the work of their lungs. She speaks to them anyway.

She murmurs words of encouragement in a time of despair.

Behind the clear plastic tarp that separates the hot zone from the clean zone at the intensive care unit, amid the low-pitched alarms of the ventilators and the high-pitched beeps of the intravenous pumps, lie 19 people. Nineteen people in a life-and-death struggle with the new coronavirus.

Remember this, Van Dyk says: they are not “COVID-19 patients.” They are people.

They are people with a virus that swept into northern New Jersey and metro New York with a velocity that stunned Van Dyk and her co-workers at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck.

In the three weeks since New Jersey’s first patient was diagnosed on March 4, the virus has caused 81 deaths statewide – 18 in Bergen County. It has caused more than 1,200 confirmed infections in Bergen County, and nearly 7,000 statewide, as well as thousands more presumed infections and complete economic and social dislocation.

Van Dyk, a critical care nurse, works in the beating heart of New Jersey’s hot zone.

Her patients are the sickest of the sick. Within them, massive battles rage.

'Angel' NYC nurse dies from COVID-19: Nurse on coronavirus front lines dies after texting sister 'I'm okay'

Connected to a hanging garden of intravenous drips, ventilator hoses and electronic monitors, their bodies are mounting an immune response to an unrecognized invader. It’s a response that itself can spiral out of control and kill the host it seeks to save.

For patients with the most severe illness, COVID-19 progresses from pneumonia to ARDS – acute respiratory distress syndrome – a neutral acronym for a frightening condition. Their lungs become so clogged they can’t meet the body’s demand for oxygen.

Clinicians speak of “ground glass opacities,” the telltale dark shadows that show up on imaging scans of patients’ lungs. They speak of cytokine storms, the overproduction of immune cells and their activating compounds – cytokines – that flood the lungs and cause inflammation or fluid build-up.

Van Dyk speaks of people: People with biographies of love and heartache, hope and disappointment, quirks and bad habits. People who now lie still and silent amid the rapid footfalls and controlled chaos of the ICU.

People with families, who, in the merciless disease’s cruelest twist, cannot visit them.

“Family interaction is part of our patient care,” she said of work in the intensive care unit. Families bring love and comfort and things that can’t be delivered through an intravenous line.

But now, “the families cannot see their loved ones, cannot be at the bedside with their loved ones, cannot communicate or interact with them.”

So once or twice a day, Van Dyk tries to connect them. She uses an iPad wrapped in plastic. The anxious families see and speak to their loved ones, she says. The patients, inert in medically induced comas, do not reply.

Her voice is calm as she describes these scenes that wrench her heart. “You know how when you’re a mom or dad, you don’t want to cry or lose control in front of your kids?” she says. “That’s how it is.”

When the outbreak started, the ratio of patients to critical care nurses at Holy Name was 1 to 1. Now it’s 2 patients for each nurse, with ancillary staff helping to run for supplies, turn the patients, and do other less advanced work.

'We are physically bringing home bacteria': Doctors fear for their families as they fight against coronavirus

Van Dyk works a 12-hour shift, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. And now she, like everyone in the unit, is picking up extra shifts. “We’re tired,” she says.

Holy Name had 100 patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 on Wednesday, 25 of them on ventilators. The numbers rise each day. The surge is just starting. State Health Commissioner Judith Persichilli predicted Wednesday that the peak in northern New Jersey will come shortly after New York’s, “in 21 to 60 days.”

“Critical care right now is pretty stressed,” the health commissioner said. “We’re seeing some strain in the northern counties, particularly around critical care.”

Terms like stress and strain barely describe Van Dyk’s world.

New Jersey was in the midst of a nursing shortage before this pandemic. It is particularly acute for critical care nurses, who receive extra training to learn to interpret lab results, read multiple monitors and respond when a patient begins to deteriorate. Not to mention how to monitor and maintain a ventilator.

Doctor dies of coronavirus: But his life's work will help fight COVID-19

Now, as nurses from other departments volunteer to help in the crisis, they are learning some of these skills.

Van Dyk has been doing this for 32 years. She graduated from Holy Name’s nursing school and immediately started work in the ICU at the hospital. A high-pressure job under any circumstances, it is more challenging these days than ever.

And there is the knowledge that things almost certainly will get worse. “We’re scared, too,” she admits.

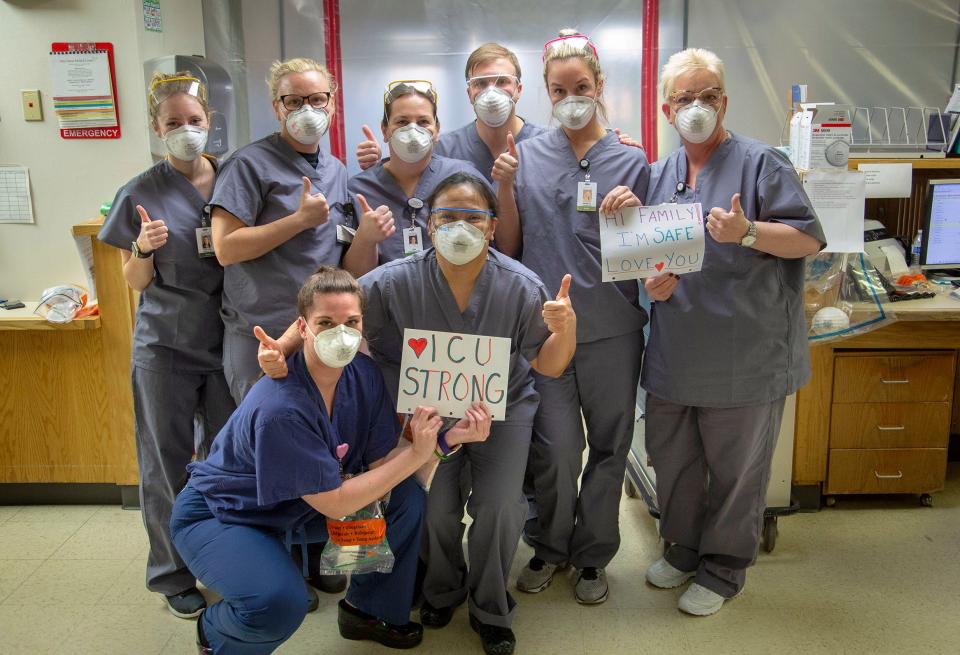

But, as always in war, there is camaraderie at the front. At the shift change in the morning, the nurses huddle with the overnight crew, then rally as a team. They watch each other don and doff protective gear, making sure the seals are tight, the protection complete against the unseen enemy. They back each other up.

If it’s hard to get up in the morning, she reminds herself: “I love that I can help others in need. It is my ethical and moral responsibility to get up and face every day, coming in and caring for these patients.” And then, “somehow, internally, I find that oomph or courage or burst of energy.”

Twelve or 14 hours later, she changes out of her scrubs back into her sweats. She climbs into her car and rolls down the windows, despite the cold. Then she cranks up the radio – 103.5 FM – and drives home to Midland Park.

She says hello and jumps in the shower. Then she sits quietly for a while, reflecting upon the day. But not too long. It’s best to stay busy.

“If you think too much,’’ she said, “you cry.”

Follow Lindy Washburn on Twitter: @lindywa

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Nurses caring for COVID-19 patients on ventilators tell what it's like

money

money