Substack isn't a new model for journalism – it’s a very old one

If you haven’t heard of Substack – you probably will soon.

Since 2017, the platform has provided aspiring web pundits with a one-stop service for distributing their work and collecting fees from readers. Unlike many paywall mechanisms, it’s simple for both writer and subscriber to use. Writers upload what they’ve written to the site; the readers pay from US$5 to $50 a month for a subscription and get to read the work.

Enticed by the independence from editorial oversight Substack offers, several media figures with large followings – including Andrew Sullivan of New York magazine, Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept, Buzzfeed’s Anne Helen Peterson, and Vox’s Matthew Yglesias – are now striking out on their own.

Substack has also elevated a few commentators – perhaps most notably Heather Cox Richardson, the Boston College historian whose “Letters from an American” is currently Substack’s most-subscribed feature – to near-celebrity status.

Hamish McKenzie, Substack’s co-founder, has compared his company’s promise to an earlier journalistic revolution, likening Substack to the “penny papers” of the 1830s, when printers exploited new technology to make newspapers cheap and ubiquitous. Those newspapers – sold on the street for 1 cent – were the first to exploit mass advertising to lower newspapers’ purchase prices. Proliferating throughout the United States, they launched a new media era.

McKenzie’s analogy isn’t quite right. I believe journalism history offers more context for considering Substack’s future. If Substack is successful, it will remind news consumers that paying for good journalism is worth it.

But if Substack’s pricing precludes widespread distribution of its news and commentary, its value as a public service won’t be fully realized.

Mass advertising subsidized ‘objective’ journalism

As a journalism scholar, I believe Substack’s subscription-based plan is, in fact, closer to the model of journalism that preceded the penny papers. The older versions of U.S. newspapers were relatively expensive and generally read by elite subscribers. The penny papers democratized information by mass-producing news. They widened distribution and lowered the price to reach those previously unable to buy daily newspapers.

Substack, on the other hand, isn’t prioritizing advertising revenue, and by pricing content at recurring subscription levels, it’s restricting, rather than expanding, access to news and commentary that, for a long time, news organizations have traditionally provided free on the web.

History has shown that the economic basis of American journalism is deeply entangled with its style and tone. When one primary revenue source replaces another, much larger evolutions in the information environment occur. The 1830s, again, offer an instructional example.

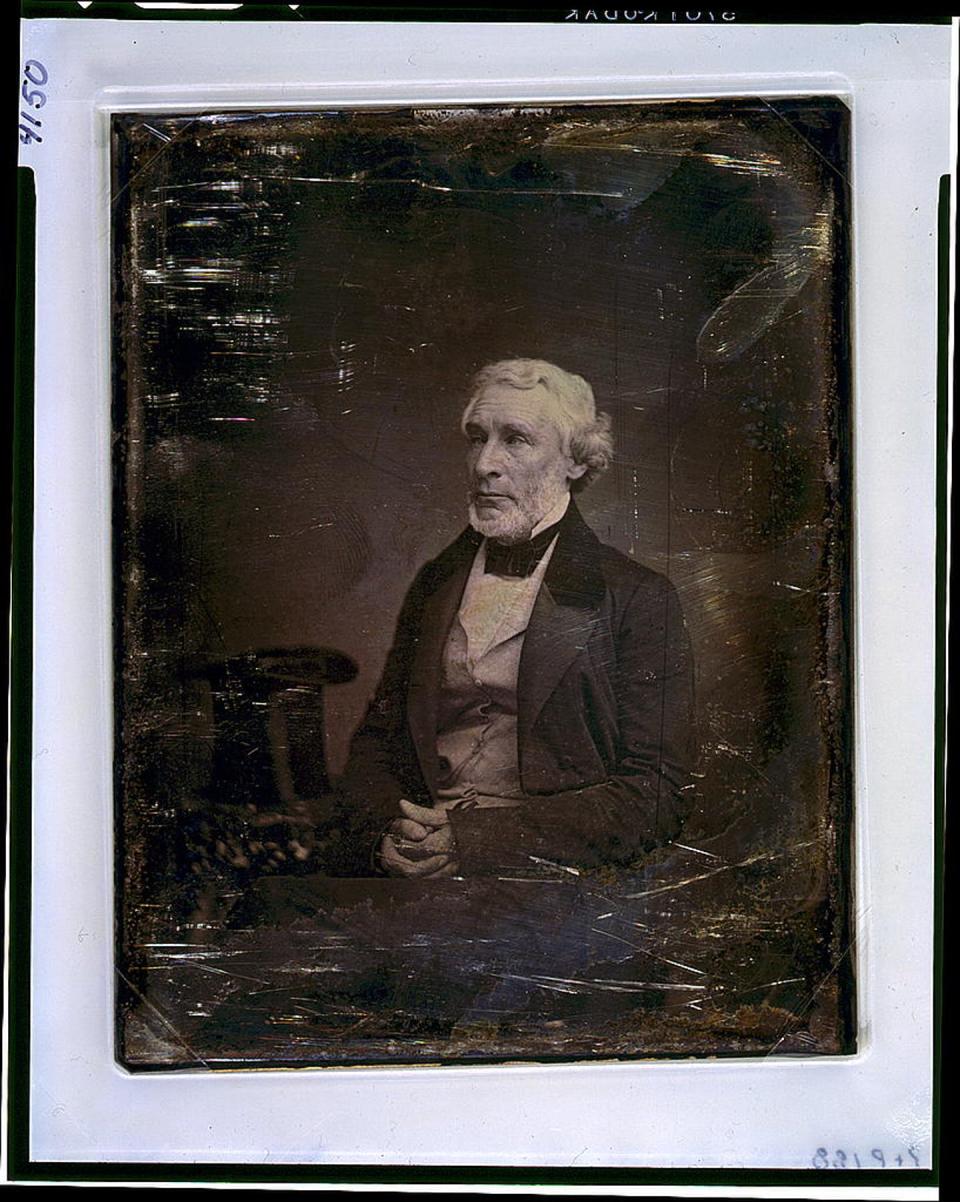

One morning in 1836, James Watson Webb, the editor of New York City’s most respected newspaper, the Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer, chased down James Gordon Bennett, the editor of the New York Herald, and beat Bennett with his cane. For weeks, Bennett had been insulting Webb and his newspaper in The Herald.

In his study of journalistic independence and its relationship to the origins of “objectivity” as an established practice in U.S. journalism, historian David Mindich identifies Webb’s assault on Bennett as a revealing historical moment. The Webb-Bennett rivalry distinguishes two distinct economic models of American journalism.

Before the “penny press” revolution, U.S. journalism was largely subsidized by political parties or printers with political ambition. Webb, for example, coined the name “Whig” for the political party his newspaper helped organize in the 1830s with commercial and mercantile interests, largely in response to the emergence of Jacksonian democracy. Webb’s newspaper catered to his (mostly) Whig subscribers, and its pages were filled with biased partisan commentary and correspondence submitted by his Whig friends.

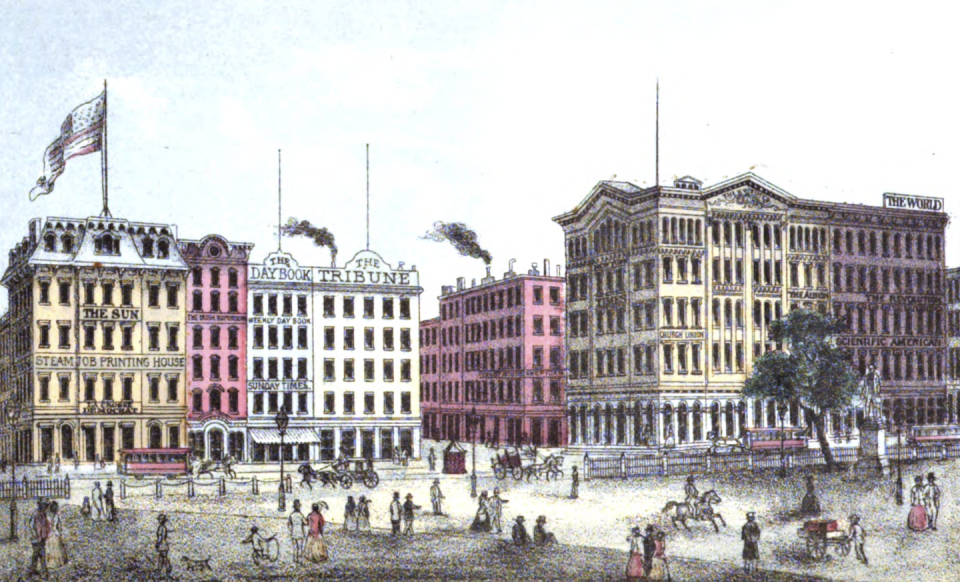

Bennett’s Herald was different. Untethered from any specific political party, it sold for one penny (though its price soon doubled) to a mass audience coveted by advertisers. Bennett hired reporters – a newly invented job – to capture stories everyone wanted to read, regardless of their political loyalty.

His circulation soon tripled Webb’s, and the profits generated by The Herald’s advertising offered Bennett enormous editorial freedom. He used it to attack rivals, publish wild stories about crime and sex, and to continually stoke more demand for The Herald by giving readers what they clearly enjoyed.

Huge circulation propelled newspapers like Bennett’s Herald and Benjamin Day’s New York Sun to surpass Webb’s Morning Courier and Enquirer in relevance and influence. Webb’s newspaper cost a pricy 6 cents for far less timely and exciting news.

It should be noted, however, that the penny papers’ nonpartisan independence didn’t ensure civic responsibility. To increase sales, the Sun, in 1835, published entirely fictional “reports” claiming a fantastic new telescope had detected life on the Moon. Its circulation skyrocketed.

In this sense, editorial independence encouraged publication of what’s now called “fake news” and sensationalistic reports unchecked by editorial oversight.

Substack: A blogging platform with a toll gate?

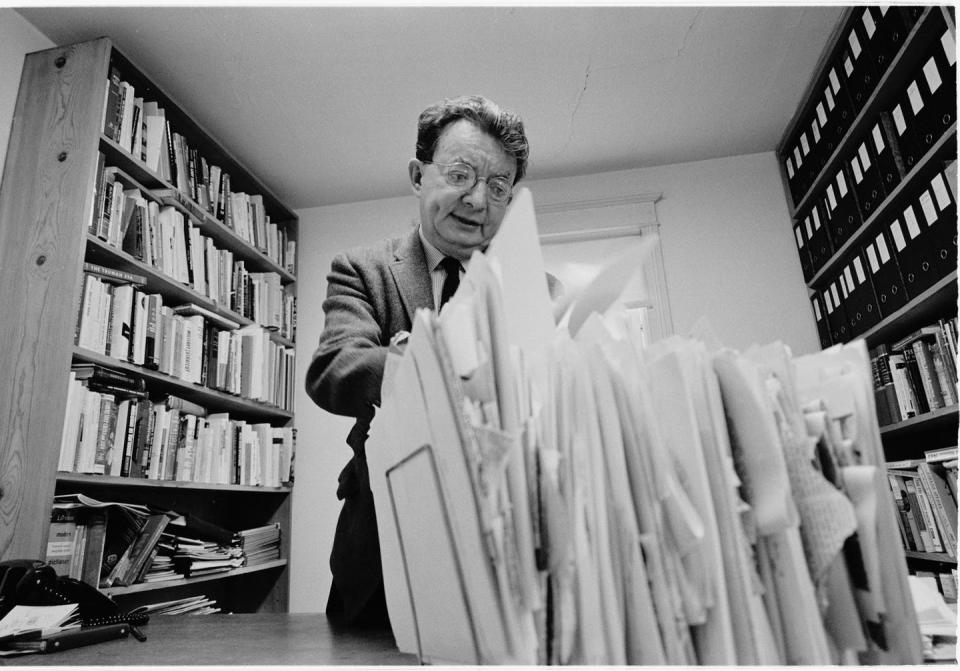

Perhaps “I.F. Stone’s Weekly” offers the closest historical antecedent for Substack. Stone was an experienced muckraking journalist who began self-publishing an independent, subscription-based newsletter in the early 1950s.

Yet unlike much of Substack’s most famous names, Stone was more reporter than pundit. He’d pore over government documents, public records, congressional testimony, speeches and other overlooked material to publish news ignored by traditional outlets. He often proved prescient: His skeptical reporting on the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident, questioning the idea of an unprovoked North Vietnamese naval attack, for example, challenged the U.S. government’s official story, and was later vindicated as more accurate than comparable reportage produced by larger news organizations.

There are more recent antecedents to Substack’s go-it-yourself ethos. Blogging, which proliferated in the U.S. media ecosystem earlier this century, encouraged profuse and diverse news commentary. Blogs revived the opinionated invective that James Gordon Bennett loved to publish in The Herald, but they also served as a vital fact-checking mechanism for American journalism.

The direct parallel between blogging and Substack’s platform has been widely noted. In this sense, it’s not surprising that Andrew Sullivan – one of the most successful early bloggers – is now returning to the format.

Information doesn’t want to be free

Even if Substack proves simply an updated blogging service with an uncomplicated tollbooth, it still represents improvement over the “tip jar” financing model and reader appeals that revealed the financial weakness of all but the most famous blogs.

This might be Substack’s most important service. By explicitly asserting that good journalism and commentary are worth paying for, Substack might help retrain web audiences accustomed to believing information is free.

Misguided media corporations persuaded the web’s earliest news consumers that big advertisers would sustain a healthy news ecosystem that didn’t need to charge readers. Yet that economic model, pioneered by the penny papers, has clearly failed. And journalism is still sorting out the ramifications for the industry – and democracy – of its collapse.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

It costs money to produce professional, ethical journalism, whether in the 1830s, the 1980s or the 2020s. Web surfing made us forget this. If Substack can help correct this misapprehension, and ensure that journalists are properly remunerated for their labor, it could help remedy our damaged news environment, which is riddled with misinformation.

But Substack’s ability to democratize information will be directly related to the prices its authors choose to charge. If prices are kept low, or if discounts for multiple bundled subscriptions are widely implemented, audiences will grow and Substack’s influence will likely extend beyond an elite readership.

After all: They were called “penny papers” for a reason.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Michael J. Socolow, University of Maine.

Read more:

How the fireside chat provided a model for calming the nation that President Trump failed to follow

Fox News isn’t the problem, it’s the media’s obsession with Fox News

Michael J. Socolow does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

money

money