Is ‘Stranger Things’ a rip-off? Aspiring screenwriter sues Netflix, Duffer brothers for script similarities

It was Will Byers’ backyard in “Stranger Things” that made Jeff Kennedy suspicious. He watched the first episode of Netflix’s streaming hit at a friend’s house after it premiered in 2016, studying the opening scenes in fictional Hawkins, Indiana.

Kennedy grew up in the Hoosier State and moved to Los Angeles to become a screenwriter. He was interested in paranormal stories — he’d written one himself based on a childhood friendship that he’d been pitching around town.

Five minutes in to “Stranger Things,” which returns for a fourth season on Friday, Kennedy noticed something that made him inch closer to the TV: The 12-year-old protagonist’s humble ranch looked really familiar. So did the surrounding woods.

When Will saw a monster through his window, Kennedy reached for a second beer. After Will disappeared from a shed in his backyard, Kennedy knew something was wrong.

He paused the credits, scouring for names he knew. He didn’t recognize the show’s creators, brothers Matt and Ross Duffer. But one lower down caught his eye: The Aaron Sims Company.

The next day he binge-watched the entire season and came to a startling conclusion: “We were robbed.”

...

Content is king in Hollywood. Like money in New York or power in Washington, D.C., it’s the commodity that drives the town. The streaming wars between networks and tech giants have only increased its value in recent years.

But what happens when creators believe their content has been stolen?

Copyright law was designed to protect original works, providing recourse through infringement lawsuits. Yet the law is ephemeral. Ideas aren’t copyrightable, only their expression — and there’s no concrete definition for expression.

The vagueness is partly by design: Lawmakers and judges are wary of stymying innovation. But some question whom the laws are protecting.

In his book, “Hollywood’s Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet,” Peter Decherney said the Hollywood studio system was built on copying. Companies invested time and resources into forging legal doctrines sympathetic to their free use of pop culture.

That can be good for consumers, Decherney suggests, allowing ideas to be built on each other. But it also means it’s extremely rare to win a lawsuit against a studio.

Steven T. Lowe, an attorney who analyzed dozens of cases for a series of articles titled “Death of Copyright,” couldn’t name any in the past 30 years.

Critics have long accused the California judicial circuit that oversees most entertainment cases of being too protective of studios. Lowe estimates that only about 5% get to trial; the rest are dismissed by judges.

Robert Rotstein, who has represented several studios over a decades-long career, including Netflix, said there is no credence to the critique, noting that other circuits around the country see similar percentages.

“The vast majority of these cases frankly don’t have merit,” Rotstein said. “If you look at court opinions, they analyze the cases closely, and find the lack of merit is a straight-forward analysis of existing law.”

Rotstein said frivolous claims of copyright infringement can impede free speech and stifle creative expression. Others in the industry say the fact that so few cases make it through the legal system has enabled a culture of theft.

Kevin J. Greene, an entertainment law professor at Southwestern Law School, questions whether plagiarism is baked into studios’ operations, particularly with the insatiable demand created by streaming channels.

“My belief is that using the ideas of people who do pitches and submissions is part of their business model,” Greene said. “They don’t outright take it and steal it. But they tailor it enough so the party who did the submission can’t say ‘That’s my work’ because copyright doesn’t protect broad concepts.”

...

Jeff Kennedy grew up in South Bend, Indiana, with all the trappings of an ’80s childhood: bikes and malls and board games and movie theaters.

Those halcyon days were spent alongside his best friend, Clint Osthimer. Becky Georgi, Clint’s mom, said they were always riding bikes and playing in the creek out back.

“Many adventures took place in those early years,” Georgi said. “They went through an Indiana Jones phase for sure.”

One time, while looking for their own Temple of Doom treasures, they found items that had been stolen from neighboring houses and dumped in the creek. Police saw them playing with the burgled goods and took them home in a squad car. After “Stand By Me” was released, they went on an expedition for their own dead body. All they uncovered was a bag of trash.

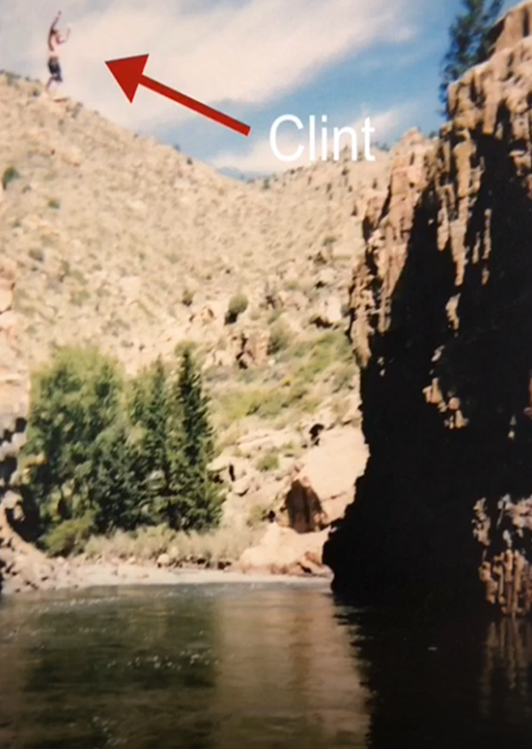

The way Kennedy remembers it, Clint was the yin to his yang. Jeff was reserved, Clint was outgoing. Jeff was timid, Clint was never scared of bullies. He loved to jump off cliffs.

Jeff always assumed his friend’s larger-than-life persona was born out of something serious. Clint was diagnosed with epilepsy in middle school. His seizures were scary and unpredictable. During one, he fell to the gym floor and knocked out his two front teeth.

“Your best friend could just be sitting there talking to you and the next moment he could collapse onto the ground,” Jeff Kennedy said.

Jeff would help by placing his hands on Clint’s shoulders during a seizure, talking him through it.

Georgi was always heartened by the way Jeff tried to protect Clint. She knew that there was a stigma around the disorder and that some kids didn’t want to be near it. Jeff sensed that, too.

Clint was quick to brush it off. Sometimes he opened up to Jeff, describing the seizures as like being in a dream — he was there but everything was upside down.

Both boys moved away from South Bend in high school, though they stayed in touch. Jeff moved on to L.A. in his 20s to be a writer. He loved movies, especially the classics they went to see as kids. But he had no experience and didn’t know what to write about. He explained his dilemma when Clint came West for a visit in 2005. Clint was confident it would work out.

A few weeks later Kennedy got a call: Clint had died in a car accident. He was 29.

The news was devastating. As he grieved, Kennedy thought back to their childhood. And how prophetic Clint had been in their last days together.

Then it clicked.

“Suddenly, I had a story to tell, and it was Clint’s story,” Kennedy said. “And I had a setting. It was where we grew up and our time together. I had themes, the themes of the way people treated him as if he were an outcast.”

...

Kennedy began writing about Clint’s epilepsy. He envisioned seizures as Clint’s personal demon and the place he went during them as a dark copy of real life. Lightning and electricity came to signify evil, a play on misfired signals in the brain believed to cause seizures.

He created Jackson Chance, a grizzled 29-year-old ex-military man with epilepsy on a quest to destroy his inner demon. And William Nerowe, a doctor and Jackson’s best friend. Their relationship was modeled on Clint and Jeff’s. In their story arcs, Kennedy tried to deliver the things he’d always hoped for his friend.

“I really wanted to tell a story where that character was empowered, that what people looked at as a weakness was a strength,” he said.

Jackson’s wife, Autumn, suffers from schizophrenia and can also see the carbon copy dimension.

Though he was inspired by his childhood home, Kennedy thought a movie needed a grander setting and changed the location to Wyoming. He came up with a title, “The Lightning Shower in Jackson Hole,” before eventually landing on the name “Totem.”

He submitted the script to the Library of Congress in 2007 to secure a copyright. He dedicated it to his friend, Clint.

He also presented it to Georgi. She was grateful that he wanted to tell Clint’s story and raise awareness of seizure disorders.

“I’m just continually struck by how much they loved each other,” Georgi said. “They were fighting the demon together.”

...

The scenes related to Will Byers’ disappearance in “Stranger Things” were what first struck Kennedy that night at his friend’s house. He’d written similar ones for Autumn Chance in “Totem.”

Early in Kennedy’s script, Autumn is washing dishes when she sees a monster named Azreal through a window into the backyard. He appears in a cave by a shed.

The next night there’s a lightning storm, and Autumn sees Azreal through the window again. This time she runs outside toward the shed, where she’s attacked by his minion wolves.

Jackson realizes Autumn is missing but is stopped by a seizure during which he sees Autumn in a cave, lorded over by Azreal. The vision convinces Jackson that Autumn isn’t dead — she has been taken to another dimension.

Kennedy felt Autumn and Will’s disappearances involving sheds in their backyards was beyond coincidence. The more he watched “Stranger Things,” the more that feeling grew.

“There were moments I’d have to wait a little bit, then sure enough, it’d come back to these primary, critical story elements pulled directly from ‘Totem,’” he said.

Kennedy saw Jackson’s disbelief over Autumn’s death — a key plot point in his manuscript — echoed in “Stranger Things” by Joyce Byers, Will’s mom. Joyce is convinced that the body found in a rock quarry and believed to be Will’s is a fake. A funeral does little to dissuade her. Autumn’s funeral has the same effect on Jackson.

William Nerowe, Jackson’s best friend in “Totem,” thinks he’s crazy but agrees to help rescue Autumn. The police chief in “Stranger Things” initially is dismissive of his old friend Joyce before going all-in to find Will.

Some of the characters were eerily similar, too, right down to their physical descriptions.

In “Totem,” Jackson and William are aided by a 10-year-old girl with a shaved head and telekinetic powers who creates a rupture between dimensions that allows Azreal to enter the real world.

As Will’s friends search for him in “Stranger Things,” they find a 12-year-old girl with a shaved head and telekinetic powers who creates a gateway to the alternate universe where Will is being held.

“One thing after the next indicated pretty quickly that they were using my material,” Kennedy said.

In July 2020, Kennedy sued the creators of “Stranger Things” and Netflix alleging they brazenly infringed on many elements of “Totem,” including characters, plot, sequence, themes, setting, mood/tone and dialogue.

Attorneys for Netflix have argued against Kennedy's claims.

“Mr. Kennedy's complaint is preposterous; we intend to continue to defend it vigorously and we expect it to be soundly rejected,” the company said in a statement. “The truth is the show was independently conceived by The Duffer Brothers, and is the result of their creativity and hard work.”

...

Intellectual property battles are as old as the entertainment industry. Thomas Edison waged legendary fights over his camera technology. Playwrights and novelists have sued Hollywood for decades.

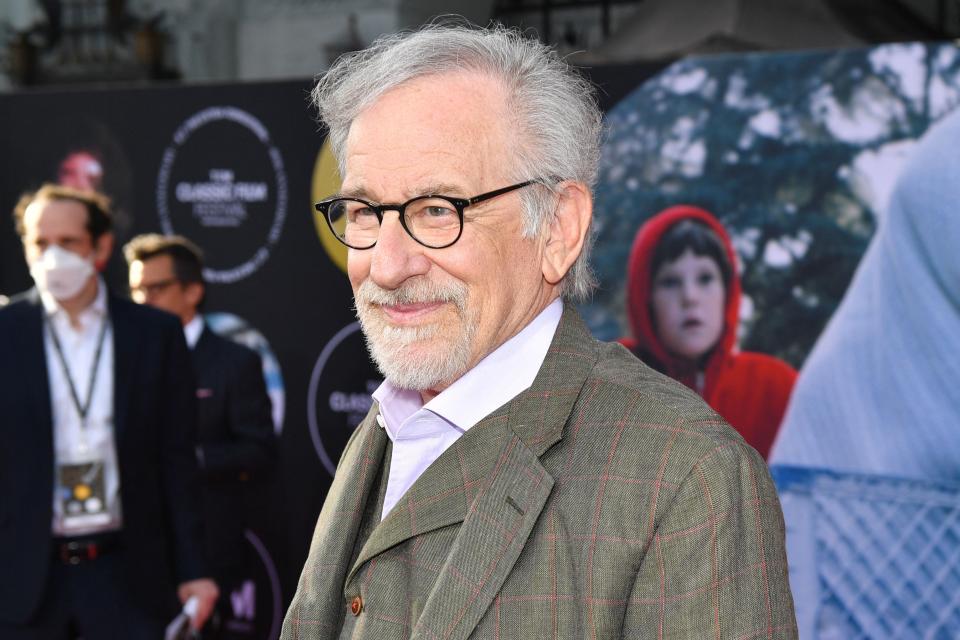

Today, experts say big hits inspire numerous allegations of copying. James Cameron’s production company was sued three times in 10 days for “Avatar.” He won all three. Steven Spielberg has won almost as many copyright cases as Oscars.

Kennedy’s lawsuit is the second over “Stranger Things.” Filmmaker Charles Kessler sued Matt and Ross Duffer, saying he shared concepts and a script for his short film “Montauk” with the brothers at Tribeca Film Festival in 2014. The Duffers called their show “Montauk” when they sold it to Netflix.

Kessler’s case made it to the eve of trial, when at the eleventh hour, he withdrew his claim. He issued a statement retracting his allegations. Netflix also issued a statement calling the lawsuit baseless and “Stranger Things” “a groundbreaking original creation by The Duffer Brothers.”

Kessler had claimed the Duffers used the concepts he pitched them without permission or compensation. Precedent for his allegation was enshrined in a landmark 1950s case that spurred Hollywood to beef up its legal insulation.

Director Billy Wilder was sued over his film “Ace in the Hole” by a screenwriter who had pitched the idea to Wilder’s secretary. She promised he’d be compensated if they used it. The court ruled the writer had a legal basis for his claim and Wilder settled before trial.

“It was after that that Hollywood started to wrap itself in this legal armor,” Decherney said.

Studio legal departments began to rely heavily on contracts and established procedures for receiving scripts. It’s now common practice to reject unsolicited pitches without opening them. Would-be writers typically need contacts or an agent to get a pitch meeting.

Critics say that has exacerbated Hollywood’s gatekeeping problem, keeping out newcomers — and diverse talent — even as the demand for new content has increased.

In UCLA’s 2022 Hollywood Diversity Report, researchers found that people of color and women made substantial gains over the past several years. They noted, however, that decisions about which films are greenlighted are still overwhelmingly made by white men.

“There’s a lot of fear in marginalized communities, particularly in the Black community, because they know about the history of appropriation and stuff being taken,” Greene said, a point he said he made at a California Reparations Task Force meeting last year.

“A lot of people simply are saying ‘I won’t play the game.’ It’s a great loss to society and to the entertainment industry.”

Filmmaker Francesca Gregorini sued Apple and the creators of the Apple TV+ show “Servant,” M. Night Shyamalan and Tony Basgallop, in 2020 alleging they blatantly copied her film “The Truth About Emanuel.”

The movie stars Jessica Biel as a new mom who finds a nanny in her young neighbor, Emanuel. The twist in “Emanuel” — and in the first season of “Servant” — is that the infant is dead, and mom and nanny are caring for a lifelike “reborn doll” used to help with grief.

In court records, Gregorini said the case goes beyond plagiarism.

“’Servant’ is meant to showcase Apple’s new streaming service,” the complaint reads. “But if ‘Servant’ showcases anything, it is the gender arrogance and inequity still infecting Hollywood.”

“Emanuel” is a nuanced portrayal of motherhood and female relationships based on personal experience. By contrast, Gregorini alleges, the all-male producers of “Servant’s” first season reframed that female-centric story through the male gaze — male characters imply the mom is crazy and question whether the nanny is hot enough to have sex with.

“It’s an apt metaphor for the real-life version of what could happen here: It takes only a few old guard Hollywood men, such as Mr. Shyamalan and Mr. Basgallop, and their new (S)ilicon (V)alley partner Apple TV+, to negate the considerable achievements and life experiences of the women behind ‘Emanuel,’ and to irredeemably tarnish their work.”

Attorneys for Apple, Shyamalan and Basgallop have fought Gregorini's allegations in court, arguing that any similarities between the works are based on common, unprotectable elements, as well as “blatant mischaracterizations designed to make these works appear more similar than they are.”

...

Kennedy created Irish Rover Entertainment and hired a production company, Evergreen Films, in 2009 to help turn “Totem” into a movie. The company suggested contracting a concept artist — a designer who creates visual representations of ideas for movies or TV shows, to help pitch studios.

The production company proposed a few options. One was Aaron Sims.

Kennedy jumped at the chance to work with Sims, who may be the foremost monster-maker in Hollywood. His credits are considerable: “Batman Forever,” “Men in Black,” “War of Plant of the Apes,” and a hundred more.

“He'll get you thinking in ways that you are not thinking,” Kennedy said. “You can kind of fool yourself into believing that you were the one who came up with the idea — he’s that good at what he does.”

Kennedy said he shared everything with Sims, down to childhood photos. And he was thrilled with Sims’ work, copyrighting a live action demo and concept art that Sims produced in 2010.

Despite the forward momentum, Kennedy had a hard time getting studios to bite. He was working stereotypical jobs of an aspiring creative in L.A. — auditioning as an extra and bartending — to keep his schedule flexible for last-minute pitch meetings.

Eventually it became too much. He cut ties with the production company and pursued corporate jobs. But he stayed in touch with Sims and his partners.

“I really believed these guys were going places,” Kennedy said. “I wanted Aaron to actually direct the film.”

Kennedy said he gave Sims another version of the script in 2014.

“I told him from the beginning, 'You have carte blanche to share this with anyone,'” Kennedy said. “I trusted Aaron that if he gave it to Steven Spielberg, the next step would be Steven Spielberg is going to have me into his office. Even if he's just going to pay me to leave, at least I would be involved.”

That’s why, when he saw Sims’s name roll by in the credits of “Stranger Things” that night in his friend’s apartment, his heart sank.

Sims declined USA TODAY’s request for comment through his company, directing a reporter to attorneys representing him and Netflix.

In his suit, Kennedy alleges infringement — by Sims, the Duffers, Netflix and production company 21 Laps, Inc. — of promotional art, storyboards, creatures, visual effects, CGI characters and the live demo created by Sims for “Totem.”

That artwork, juxtaposed against still frames from “Stranger Things,” makes up the bulk of exhibits in the case. One depicts Autumn Chance seeing a monster through a window into her backyard, alongside a still with Will Byers seeing a monster in his.

Others show both monsters, standing on two feet with dangling arms and triangular heads that open to rows of teeth. Still more show tunnels that are part of alternate dimensions in both works.

...

Access is a fundamental part of copyright law. Someone can’t copy work they’ve never seen.

In the “Servant” case, the alleged access is straightforward — Gregorini’s film was released in theaters and today is available for purchase on iTunes and Amazon.

Much of Kennedy’s lawsuit centers on Sims: his access to “Totem” on one hand and his work with Matt and Ross Duffer on the other.

The Duffer brothers had a rocky entry into Hollywood. In 2011, Warner Bros picked up their first movie, “Hidden,” and hired them to direct. The studio brought in Sims to help, introducing him to the Duffers. But the brothers have said in interviews the project lost the attention of studio executives and was released straight to video. Their next credit was a writing job in 2015 for Shyamalan’s Fox series “Wayward Pines,” where Sims was also a concept artist.

“By the time we came out of that show, we were like, ‘OK, we know how to put together a show.’ And that’s when we wrote ‘Stranger Things,’” they told Rolling Stone.

The project, originally called “Montauk,” was based on an urban legend of secret governmental studies into aliens and mind control at Camp Hero in New York. The Duffers set it in the 1980s and, in interviews, said they drew inspiration from their favorite movies and writers of the era.

They pitched it to Netflix in 2015 with a pilot script, a “look book” illustrating their ideas and a video trailer filled with imagery from Spielberg and John Carpenter movies. The cover of the “look book” was the paperback of Stephen King’s “Firestarter” with the title “Montauk” and a fallen bike pasted on top, the brothers told The Daily Beast.

A little more than a year later, the show was released — an incredible turnaround time that the Duffers have called frenetic. They were still writing episodes while casting and building out the team.

“At that point, we just had the pilot script and we had so little material that we were actually having them audition with scenes from ‘Stand By Me,’” Ross Duffer told Rolling Stone.

Sims was one of their hires. He’s credited in the first two seasons of the show.

...

In addition to access, two works must be “substantially similar” to prove infringement. As with most things in copyright law, what rises to that level is amorphous.

“It’s more than just the plot,” said Philippa Loengard, director of the Kernochan Center at Columbia Law School. “It doesn’t have to be word for word. It has to be clear to the average viewer that no one could have developed this without input from or inspiration from another source.”

Though a writer may copyright a script, individual elements in that script may not be protected. Facts, like ideas, are not subject to copyright. Genre tropes, like time travel or creepy aliens, called “scènes à faire,” are also unprotectable. In a famous case brought by the creators of “Star Wars” against “Battlestar Galactica,” a judge ruled that no one can own warfare in space.

Similarly, Loengard said a shed is not copyrightable. It’s too common a storytelling device. But a main character being abducted from a shed and taken to another dimension by an evil monster, prompting a loved one to embark on a quest to get them back? That’s closer, she said.

The question of what is protectable has been at the heart of several recent 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals decisions.

Two writers and a producer sued Disney for allegedly copying a screenplay they had pitched the company in 2000 called “Pirates of the Caribbean.” Disney didn’t buy it. But in 2003 the company released the first film in the franchise with the same name.

Disney argued in a motion to dismiss the case that the movie and screenplay are not remotely similar. The judge agreed, ruling that the similarities were too common in pirate stories to be protected, and tossed it out.

Lowe filed an appeal on behalf of the writers arguing that the judge applied the wrong test.

Two tests have been developed in case law to determine substantial similarity: the “filtration test” weeds out unprotectable elements and determines similarity based on what’s left; the “selection and arrangement test” allows unprotected elements to be considered protectable if they’re selected or arranged in an original way.

In the “Pirates of the Caribbean” appeal, Lowe asserted the “selection and arrangement test” is the correct method, contending that although the screenplay does include common elements like treasure and ships, they’re strung together in a unique way.

The appeals court agreed, saying both “begin with a prologue that takes place 10 years prior to the main story; introduce the main characters during a battle, at gunpoint; involve treasure stories that take place on islands and in jewel-filled caves; include past stories of betrayal by a former first mate; contain fearful moments driven by skeleton crews ...”

“To be sure, there are striking differences between the two works, as well — but the selection and arrangement of the similarities between them is more than de minimis.”

A similar pattern has played out in the “Servant” case. Apple and Shyamalan argued that a mother who believes a therapy doll is alive is unprotectable because it’s taken from real life and “found in countless movies, television programs, and other works.”

A district court judge agreed. However, the appeals court reversed that decision, saying it was premature to rule whether such elements are tropes without expert testimony.

...

Kennedy’s case also hinges on substantial similarity. His exhibits include a laundry list of alleged overlap.

There are big things, like the parallels between Jackson Chance in “Totem” and Joyce Byers in “Stranger Things,” and their quests to rescue their loved ones from monsters in alternative dimensions. Both protagonists are guided by their loved ones’ drawings, which they use as navigation, as well as the young girl with supernatural powers and a shaved head.

Seizures and visions are central plot devices in both. Jackson’s epilepsy in “Totem” gives him visions of the monster and alternate dimension. Will Byers experiences the same in Season 2 of “Stranger Things.”

Lightning and electrical currents also indicate the presence of the monster in both tales and the monster has shape-shifting minions — wolves in “Totem” and dogs in “Stranger Things”.

And there are smaller things. Both have haunting industrial buildings (a psychiatric hospital in “Totem” and a government building in “Stranger Things”); inanimate objects are used to communicate with missing loved ones (dreamcatchers in “Totem” and Christmas lights in “Stranger Things”); protagonists’ homes are in valleys in the alternate dimensions (the “Valley of Death” in “Totem” and “Valley of Shadows” in “Stranger Things”).

Then there are the baffling coincidences.

Kennedy said he saw “Girl, Interrupted,” starring Winona Ryder, while developing his script and wrote Autumn in her likeness. They developed posters with resemblances of Ryder in hopes of casting her in the role.

“She just had this energy that was perfect for Autumn,” Kennedy said. “She was legendary in ‘Beetlejuice,’ and you name it, ‘Edward Scissorhands.’ But she was kind of in a downturn in her career and was off the radar.”

Ryder plays Joyce Byers in “Stranger Things,” her first major role in years. Her casting was hailed in the press with headlines like “Why We’ve Missed Winona Ryder and How ‘Stranger Things’ Brought Her Back.”

Attorneys for Netflix, the Duffers and Sims have argued that the two works are objectively different “in virtually every imaginable measure.”

In their motion to dismiss filed in December 2020, they argued the only similarities between “Stranger Things” and “Totem” involve the rescue of loved ones who have been abducted by a monster and taken to an alternate dimension — which they say is a general concept and not protectable.

They also emphasized the differences between two works. Child characters play a secondary role in “Totem” but are central to the story in “Stranger Things.” Kennedy pulled pieces from Native American folklore in “Totem,” including totem poles, dreamcatchers, shamans and medicine men — none of which exist in “Stranger Things.”

“A lot of these complaints will on their face look like they're similar, what the plaintiffs do is they pull out a lot of random, scattered similarities. And they make a list and say ‘Hey that’s similar.’ And a lot of people without experience in the area will say ‘Hey that sounds real similar,’” said attorney Rotstein, who is not involved with the case. “But if you look at the works themselves there are no similarities at all.”

...

In early 2021, Kennedy’s suit survived its first big test. The judge denied Netflix’s motion to dismiss. The opinion was spare, noting only that expert testimony may be needed.

The judge, Consuelo B. Marshall, is the same one who was overruled in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” case. Along with the “Servant” case, it was one of a string recently overturned by the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

Those appellate court opinions have provided a glimmer of hope for creatives.

“Is this a possible swinging of the pendulum to correct a miscarriage of justice often times?” Lowe said. “I’d like to think that it is.”

Kennedy still has a large hill to climb. The case is currently in discovery, where both parties gather and exchange facts.

“Then it becomes battle of experts,” Loengard said. “You’re asking a third party to either justify or undermine why someone chose a specific setting or theme. That’s tough.”

Some of the most painfully recognizable elements for Kennedy may not be protectable. Experts, and ultimately a jury, may determine they’re too common to constitute plagiarism.

In the Netflix series, Kennedy sees his relationship with his best friend play out onscreen.

He sees his childhood in the way the kids ride their bikes in packs through town. Their games of Dungeons and Dragons. How they battled demons together.

He sees himself when Mike Wheeler holds the shoulders of his friend Will Byers as he’s having a seizure.

Those are the very things that stood out to Georgi, Clint’s mom, as she watched “Stranger Things.”

“I just felt really sad for Jeff,” Georgi said. “What had been an effort to honor his friend, and I think to some extent really demystify a seizure disorder ... was powerful to me. To see it taken from him, it was just heartbreaking.”

Cara Kelly is a reporter on the USA TODAY investigations team, focusing primarily on pop culture, consumer news and sexual violence. Contact her at carakelly@usatoday.com, @carareports or CaraKelly on WhatsApp

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: ‘Stranger Things,' Netflix copyright lawsuit claims show is a rip-off

money

money