South Asian brides are sounding the alarm over make-up ‘scams’

Khadija Fazal almost had the perfect wedding day. Her dress was beautiful. She and her husband made their grand entrance in a helicopter. Contrary to the weather forecast, there wasn’t a speck of rain. But all of this is shrouded by the memory of how much she hated her make-up. “I never look at the pictures,” the 30-year-old says. “They remind me of how sad I was.”

Last month, a TikTok video went viral declaring the south Asian make-up industry “a scam”. The video responded to a prompt on the platform, one that asked people to highlight a scam “so normalised [that] we don’t realise it’s a scam any more”. “Bridal make-up,” came the reply in question. “Why are all these make-up artists charging £900 minimum?”

The video, which has been watched almost 800,000 times, has sparked a fierce debate around the cost of make-up artists and other popular industry practices. Many people complained that they felt the prices were “unjustified”, as the make-up would be washed off at the end of the day. Artists, meanwhile, have argued that the bride’s look is integral to her day and would be remembered forever in photographs. The costs, they say, are necessary.

But then there are people like Fazal, who forked out hundreds of pounds to a trusted professional, only to be left devastated by the results. “She hadn’t concealed imperfections on my face properly and my eyelash was coming off,” Fazal recalls. “All I remember is walking out and going into the bathroom and crying. You pay such an extortionate amount of money; you’d think they should provide a quality service.”

There is no industry standard when it comes to make-up prices. Figures greatly vary from one professional to the next and are often determined by a specific set of criteria: their years of experience, where they are based, and how popular they are on social media. There’s also the huge demand. The UK wedding industry is worth an estimated £14.7bn, and is currently enjoying an upswing following almost two years of cancellations and postponements due to the pandemic. Typically, south Asian brides can expect prices of around £200-£300 from less popular, less experienced make-up artists. Even at the lower end, this is more than double the average UK spend of £70 on bridal make-up. Most tend to charge between £600-£800 per bride, while the most prestigious – or those with the biggest online followings – charge upwards of £1,000.

Maryam Khan*, 37, also had a disappointing experience on her wedding day. She paid her make-up artist £400 and asked for a “soft, dewy glow”. He told her to “just go with it” and opted for bright colours instead. “At the end, I told him I didn’t like the blush (it had a purple hue) and asked him to tone it down. He acted a bit offended and minimally adjusted it.” Khan says she felt “conscious” of her make-up for the duration of the day and couldn’t properly relax or enjoy the event as a result.

Since that viral TikTok video, social media has been awash with similar testimonials from people left dissatisfied by their make-up artists. One popular criticism is the number of artists charging “additional costs” on top of the price of make-up. These include travel and parking fees, and charges for working unsociable hours.

@user22277700762567157777 #stitch with @debtcollective am I wrong? 🤷🏻♀️ #scam #fyp

♬ Love You So - The King Khan & BBQ Show

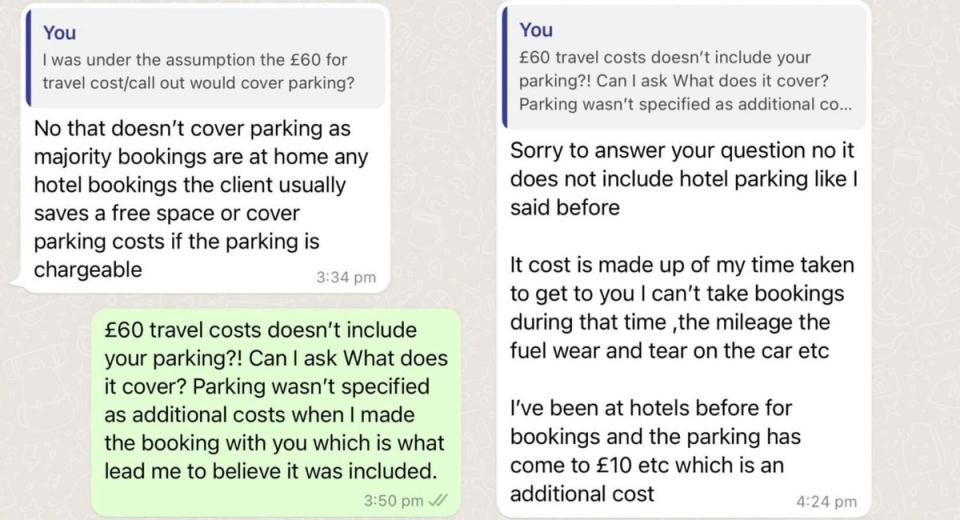

Marieha Mohsin, 33, was recently charged £60 by a make-up artist for an hour’s worth of travel, which she says felt “excessive”. When queried on this, the artist said the cost covered her time for travel, her fuel, and wear and tear on her car. Two days before the event, the artist contacted Mohsin and asked her to ensure there would be space for her to park her car outside the venue, and that it would be paid for. “We went back and forth on this as I was quite unhappy,” Mohsin said. “We already agreed the terms and conditions when I paid my deposit. You can’t then [give] me additional costs 48 hours before [the] wedding when I have a thousand things to do.”

The comments have not been well received by some professionals. One of the industry’s most sought-after names, Ambreen Ahmed of Ambreen Make-Up has more than 20 years of experience as a make-up artist and 15 years working with south Asian brides. She says the backlash feels like the “targeting and singling out of a female-dominated industry”. She explains: “It has provided a means of income for many women out there and being a make-up artist is now seen as a valid career. You can’t put a price on art, and make-up is art.” Based in northwest London, she charges between £750-£800 for clients in the capital. Those outside of London can expect to pay more. For example, a bride in Birmingham will be charged around £900.

Ahmed says criticisms aimed at the industry for charging “too much” fail to consider the long, unusual working hours required by the job. “Sometimes I leave my house at 3am, and I don’t get back until 8pm,” she says. “I spend three to four hours with each bride, making sure everything is perfect for them, and that they feel amazing. But my work doesn’t end with the bride. When I get home, I need to wash my brushes, sanitise my kit.” She says there are also costs associated with the business that go beyond keeping expensive make-up kits stocked. “My products are constantly being replenished, but on top of that, I have an administration team to pay for, accountant fees and marketing fees.”

Bridal make-up artist Tanjia Syed is popular on social media and usually booked up one to two years in advance. She insists that professionals “only want our clients to be their utmost happiest with what we’ve done”, and that the debate surrounding the industry has given online trolls a platform to harass artists based on “hearsay”. “At the end of the day, no one is forcing anyone to book a specific artist, it is up to the client to do their due diligence and research the service providers that they are interested in,” Syed says. “There are plenty of resources online for that, [and] social media enables you to contact other parties within the wedding industry to get their perspective and opinions on other service providers for an honest review.”

Many women have criticised the use of social media followings as a metric for cost. Though Ahmed boasts a wealth of experience and good repute, her 70,000+ Instagram following is modest compared to some of her peers. This includes artists who have been working for five years or less but have upwards of 200,000 followers. Some people have accused artists of lying about the quality of their work online. Several women who spoke to The Independent said their make-up artists had shared pictures of their made-up faces on their Instagrams, but only after having digitally smoothed out their skin, edited the pigment of their make-up and even changed their features. “A lot of these make-up artists post heavily edited pictures and Facetune [their] clients to give them more Eurocentric features and lighter skin, and then complain that the client has unrealistic expectations,” Mohsin says. Chandni Limbachia, a make-up artist from Leicestershire, says a tell-tale sign of whether an artist has edited their clients’ pictures is if the texture of the skin looks natural. “The reality is you are going to see some imperfections on my page,” she says. “It’s important that as make-up artists we don’t mask that up.”

Many claim that large, influencer-like followings and high demand is allowing bad behaviour to go unchecked. Mohsin and her sister discovered their make-up booking for a wedding event was in peril because they happened upon a post on Instagram. The person they had hired – and paid a deposit for – had asked her followers if any other artist could take on some of her work. Specifically on the same date and at the same venue as Mohsin’s booking. Worried, the sisters messaged and called the artist, but they were ignored. Some days later – and 10 days before the event – the artist responded. She said she could no longer do the booking as she had a family event, and returned the deposit. But by that time it was too late for Mohsin to find a new artist. She was left without anyone to do her make-up. “I think we have done this,” Mohsin says. “We’ve given them this power. They have so many followers on social media that they behave like celebrities, like they are untouchable. We don’t have any protections. If it was the other way around and I cancelled the booking at the last minute, I would have lost my deposit.”

We’ve given them this power. They have so many followers on social media that they behave like celebrities, like they are untouchable

Marieha Mohsin, client

When asked how they respond to unhappy clients, both Ahmed and Limbachia said they have never had someone complain about their work. Fazal, Khan and Mohsin each recalled incidents of not being satisfied with their make-up, but in each situation their concerns were either ignored or brushed aside by the artist.

Shortly after the TikTok video went viral, the phrase “scam MUA” began trending on social media. The term scam – to intentionally deceive or defraud someone – is undoubtedly an overreach for the unpleasant experiences being described, but the tactics being used by artists play on people’s psychology, says psychotherapist Nova Cobban. She points to the use of added last-minute costs and a fostered sense that clients need to comply with them or risk losing a make-up artist for an important life event. “You’ve already said the first yes by paying the deposit, so now you have a sense of obligation to continue to say yes or you can’t get the service,” Cobban says. There’s also the concept of “authority bias” – our propensity to agree with somebody that we see as an authority figure, or in this case, an expert in their field with a big social media following. “People feel uncomfortable asking questions or calling the artists out. The last thing you want is to put yourself in a position where you can be shamed online.”

The TikTok video is “the first time this debate has come to our attention,” says Rima Barakeh, a wedding expert and the deputy editor of Hitched.co.uk. “As a leading wedding planning platform, we haven’t been made aware of any complaints of this nature from our community of vendors, engaged couples or newlyweds.”

But while make-up artists have fiercely rebuked many of the criticisms sent their way, the sheer size of the backlash highlights that a problem definitely exists. It’s not only a few brides that have had negative experiences. Make-up artists everywhere need to start paying attention.

*Not her real name

money

money