Review: ‘New York, New York’ Needs to Make a Brand New Start of It

Some days, New York City may be exhausting, but a Broadway musical about New York, celebrating New York, should never be. Sadly, New York, New York (St. James Theatre, booking to Nov. 19)—despite the resounding presence of that classic “these vagabond shoes,” “if I can make it there” anthem—is a stodgy slog of a show loosely based on Martin Scorsese’s 1977 film.

The musical is one of those productions where you can see the cogs furiously turning, but ultimately for low returns and to baffling ends—with a central love story so unconvincing and borderline-alarming that instead of rooting for the couple to be together you hope against hope the female lead character kicks her male counterpart to the curb, and goes it alone. She’d fare much better, and certainly deserves much better.

Review: Sean Hayes Plays a Dark Rhapsody in ‘Good Night, Oscar’

Here we are in Manhattan, right after World War II. Beowulf Borrit’s stage design is busy with iconic buildings, bridges, tenements, teeming streets filled with New Yorkers of all kinds rushing about, and (gloriously) flashing neon signs, including one that fires to life right at the beginning blaring “New York, New York.”

“I love this city!” the electrician clinging to it, happy to see its bulbs blaze into life, shouts. The audience, hometown or not, cheers his expression of postwar joy; in another very different era we have watched the same city falteringly reawaken after the pandemic.

If the show’s love for its city is fervent and shared by many in the audience, the dramatization of it is muddier and filled with stereotypes and story echoes of other New York stories. Very little feels original in New York, New York; instead, this musical, directed and choreographed by Susan Stroman, feels like a reheated casserole of so many other romanticized New York narratives, stereotypes, and well-worn signifiers. The big numbers don’t feel that big, the joints linking story and music—by Kander and Ebb, with additional lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda—are creaky.

The story begins with all the characters dreaming of their own individual New York ambitions, but the principal focus falls on Francine Evans (Anna Uzele), a Black singer, and Jimmy Doyle (Colton Ryan), an Irish musician—softened transpositions of the Liza Minnelli, Robert De Niro movie characters. Francine has zip, Jimmy is grieving the loss of his brother.

Francine Evans (Anna Uzele), left, and Jimmy Doyle (Colton Ryan) in 'New York, New York.'

His best friend, Tommy Caggiano (Clyde Alves), so prominent at the beginning, fades away to occasional-dancing-figure as the show goes on, even if he has one of the best definitions of the city. New York City is the greatest social experiment ever. Everybody lives here. And everybody’s natural enemy lives here. And we manage not to kill each other. For the most part. For Jimmy, New York is the “major chord,” where music, money, and love are the battlefields to master—he just gets muddled in which order.

Madame Veltri (Emily Skinner) is a violin player and teacher, waiting for her son to return from war; Alex Mann (Oliver Prose), an immigrant from Eastern Europe, seeks her help. Jesse Webb (John Clay III) is a Black former soldier and musician, while Mateo Diaz (Angel Sigala) is a young queer Cuban who wants to save both himself and his mother Sofia (Janet Dacal) from her abusive husband—and to dress her in a beautiful golden dress.

These stories pass through a laboriously predictable narrative mincer, with not enough detail beyond the most broad-brush to give the actors room to play. The villain of the piece is an exploitative white impresario, Gordon Kendrick (Ben Davis), who spies Francine’s shining talent and seeks to make money from it—though the musical doesn’t know how much of a villain to make him, until he finally makes his overt racism clear to Francine. In the bizarre spirit of the show, even this moment is fluffed. It looks like she punches him (great!) but then says she didn’t mean to (oh!)—at precisely the moment in the show where such a punch would be entirely merited and audience-pleasing.

'New York, New York.'

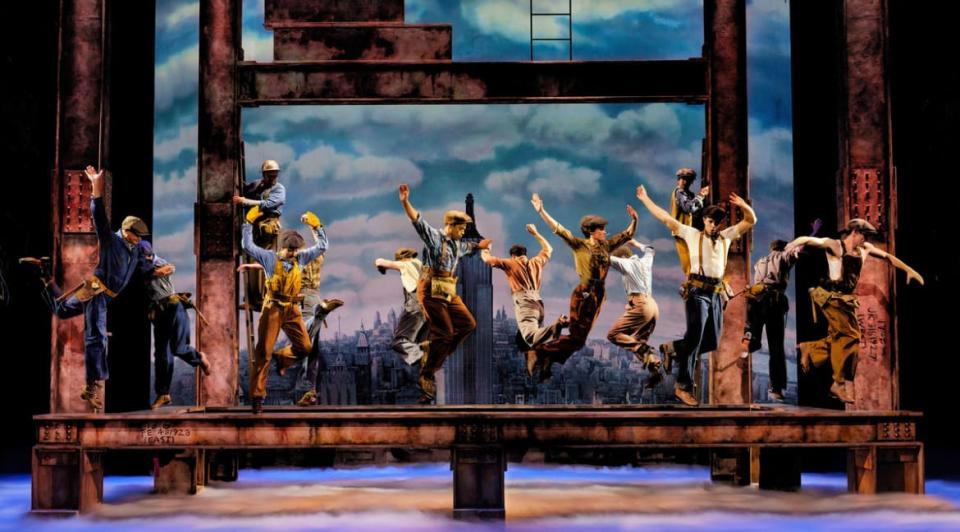

There are some odd song-dance sequences that should feel more exhilarating or stage-filling than they do, such as a group of scaffold workers dancing on beams—but the beams are just a few feet above the stage; the sense of scale isn’t one of wonder. A rainy day, with a group of anonymous pedestrians bustling around with umbrellas, isn’t rendered as a moment of lyrical urban ballet, but—well, a bunch of people wandering around with umbrellas. A celebration of “Manhattanhenge”—those one-off summer days when the sinking sunset aligns perfectly with some of the city’s main thoroughfares—is beautifully sung, if randomly beamed in from Hair.

Weirder is the relationship between Francine and Jimmy. Presumably unintentionally, his initial overtures and courtship of her feels more pest-like than cute. She has stuff to get on with, but he begs and harangues her into seeing him. While it is notable the musical centers people of color—Francine, Jesse, and Mateo—their stories are undertold; it is Jimmy who sucks up the oxygen and around whom they all orbit.

There is one well-written exchange between Francine and Jimmy, the kernel of which could and should be further developed. “How do you feel about taking the service elevator to your dressing room?” Jimmy asks about Francine going on tour as a Black female singer in that era of segregation. “Or eating in the kitchen with the help. And God forbid you put so much as your toe into one of their swimming pools.”

“Do you really think you need to explain this. To me. I live in this skin,” Francine tells him. “Jimmy, why can’t you be happy for me? I’ll tell you why… Because someone is doing things for me that you can’t.”

These are both good, emphatic points and building blocks for drama (even if Kendrick is a fairly obvious louse). The problem with New York, New York is that Jimmy is a charisma void. His eventual marriage proposal to Francine plays like hectoring harassment rather than romantic. Are we supposed to find him as obnoxious and irritating as he seems? At the end he says, rightly, it is dumb New York luck that he ends up succeeding in the club band he co-founds with Jesse and Mateo, and he is right. He meets them by coincidence, and everything works out for him. With his odd, indecipherable crooning and general air of eye-rolling insouciance, Jimmy rises with a modicum of effort and opposition.

Even Francine by the end, despite having a much better voice and can-do spirit, is asking him for help. There is nowhere like New York, the musical insists, with magic and opportunity on every corner, yet ultimately the show unintentionally—but meaningfully—presents the opportunities afforded to marginalized groups to be in the gift and dispensation of the most lackluster of white men.

Uzele’s performance, and Francine’s story, is the energy that New York, New York should be built around—even if right now the show undermines her role, agency, and independence. This self-sabotage is in the generally puzzling spirit of the show, which at least goes for broke with its stage-ablaze rendition of “New York, New York” at the end, led by Francine, encouraging the audience to sing along. You may well do, but—unlike its airplay after the New Year’s ball drop in Times Square—this time “start spreading the news” feels flat.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

money

money