Religious objectors in York County and PA: Exploring ‘the other side’ of the Civil War

Every five years since the Battle of Gettysburg, interest in the Civil War is renewed.

Many Civil War writers and researchers give more focus on the military and political parts of this bloody conflict. Family researchers wade deeper into the military service of their ancestors.

Yet there’s research probing what some call “the other side” of the war – religious objectors who refused military service as a matter of conscience.

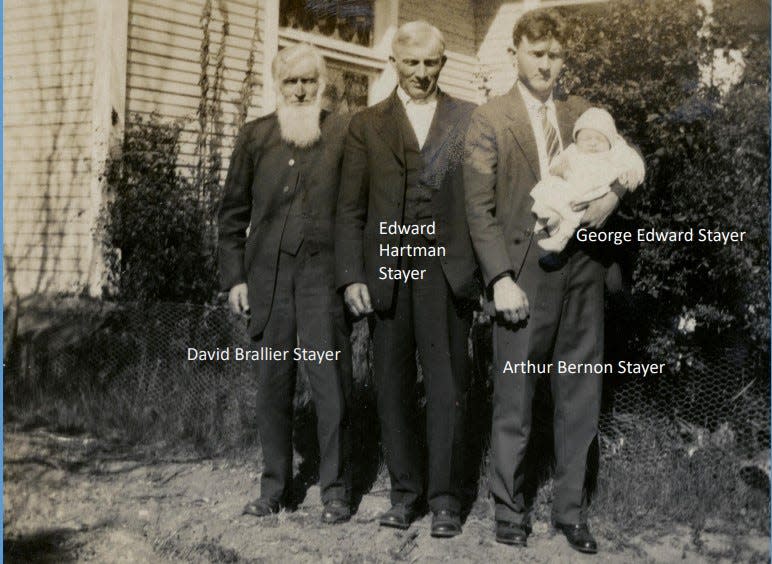

Jonathan Stayer, retired reference archivist at the State Archives and a York County resident, is working to better understand these conscientious objectors. He can look at his own family as examples.

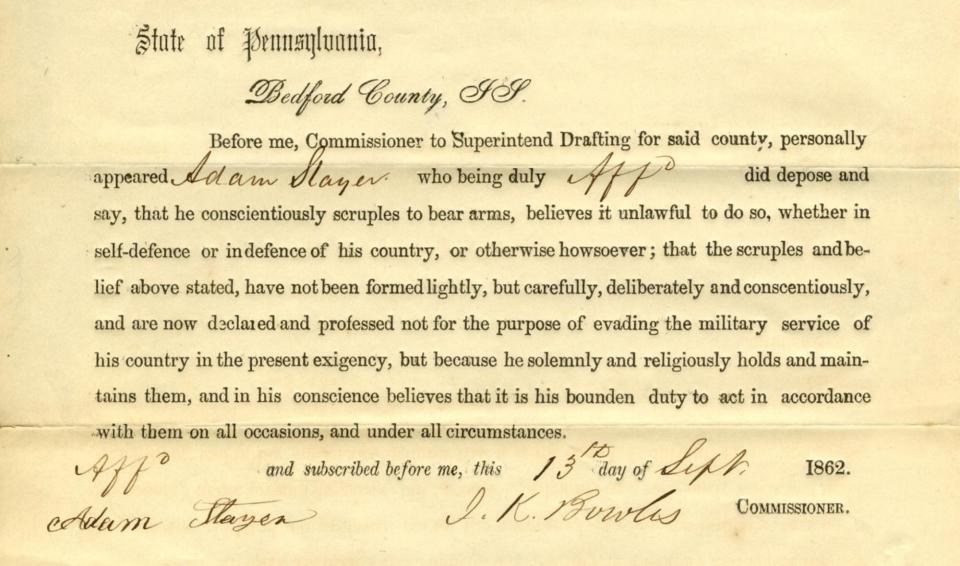

Adam Stayer and the draft

That Civil War-era family story starts with Adam Stayer who lived in Bedford County, Jonathan Stayer’s third great-grandfather and a member of the German Baptist Brethren, “Dunkers” or “Dunkards.” Known today as the Church of the Brethren, this Protestant denomination had origins in the Anabaptist branch of the Reformation, like the Mennonites.

“These Brethren opposed military service based on their understanding of the Bible,” he wrote in an email, “particularly the New Testament and the teachings of Jesus (for example, ‘love your enemies’ -Matthew 5:44).”

In the summer of 1862, the federal government called upon the Northern states for a draft of men between 21 and 45 years in age. Thirty-eight-year-old Adam Stayer fell within that group.

But the draft did not necessarily mean that he would serve.

More: Could you have a Hessian in your family tree? (I do) (column)

More: Camp Security discovery unearths insights into Revolutionary War

The Pennsylvania Constitution provided an exemption for military service: “Those who conscientiously scruple to bear arms, shall not be compelled to do so, but shall pay an equivalent for personal service.”

State government, then administering the draft, permitted conscientious objectors to file depositions seeking exemption from service, and Adam did so.

Later under federal conscription, though not immediately subject to being drafted, his name was pulled for military service in 1865. Eventually, he was exempted for “feebleness of constitution,” seemingly accurate because he died a year later at the young age of 42.

Interestingly, Adam’s brother David was exempted from service for another health issue: A loss of teeth in his upper jaw made him unfit - soldiers used their teeth to bite off the ends of musket cartridges.

About those refusing military service

The story of Adam Stayer provides a sample from one family, leading to other questions about those in the Civil War era who refused military service for religious reasons.

Stayer responded to five questions:

Q. You have said that York County's conscientious objectors numbered 156 in 1862, sixth highest among Pennsylvania's counties. And that Pennsylvania led the nation in number of conscientious objectors in the war. Is there a section or parts of York County with the highest number of those declining to serve for religious reasons?

A. Just for you, I did a quick inventory of the townships named in the 1862 Register of Aliens and Persons Having Conscientious Scruples Against Bearing Arms, and as you can see below, the conscientious objectors were pretty well scattered throughout York County, with the most (33) residing in Heidelberg Township — Mennonite and Brethren families.

The second highest number (15) in Washington Township most likely represents the German Baptist Brethren in the Bermudian area that emerged from the German Seventh-day Baptist settlement that was a branch of the Ephrata Cloister group, which I know is of interest to you.

The men in Newberry Township would be Quakers, the men in Windsor Township probably Mennonites. I have not done a detailed analysis of the objectors in York County; this is an area that certainly could use more attention.

The count: Carroll Twp ,1; Codorus Twp., 2; Dover Twp., 11; Fairview Twp., 4; Fawn Twp., 3; Franklin Twp., 3; Glen Rock, 1; Heidelberg Twp., 33; Hopewell Twp., 3; Jackson Twp., 6; Manchester Twp., 1; Manheim Twp., 2; Monaghan Twp., 4; Newberry Twp., 10; North Codorus Twp., 13; Paradise Twp., 7; Peach Bottom Twp., 1; Shrewsbury Twp., 5; Springfield Twp., 4; Spring Garden Twp., 5; Washington Twp., 15; West Manchester Twp., 3; West Manheim Twp., 2; Windsor Twp., 10; York Twp., 7.

Q. You have called the Historic Peace Churches - Mennonites/Amish, Dunkards (Brethren) and Quakers - 'the other side' of the Civil War. Please explain.

A. Because of York’s proximity to the great battle of Gettysburg and because Pennsylvania contributed significant numbers of men and amounts of resources to the Union war effort, most Civil War research in this area has focused on the military and political aspects of the conflict.

Even research on civilians tends to emphasize the impact of military and political events. And genealogists are eager to prove the military service of their ancestors.

Few historians and genealogists are interested in those men who refused military service for religious reasons. For religious objectors, the war was more than patriotism, flying flags and “glory” on the battlefield, it was a crisis of conscience.

How would they remain true to the teachings of a faith that required them to reject military service as a legitimate response for a follower of Christ? The story of the Historic Peace Churches is more about peace than about war.

Maybe if more Peace Church members had been involved politically, both North and South, such a devastating war might have been avoided.

Q. Generally, how did conscientious objectors gain an exemption from serving? Did they hire substitutes? Or serve in non-combat positions?

More: Of Pennsylvania's conscientious objectors: The 'other side' of the Civil War

More: Finding community and membership in remote York County

A. In 1862—in Pennsylvania—objectors escaped conscription by filing conscientious objector depositions such as the one submitted by Adam Stayer, or by being determined to be physically unfit for military service. Under the federal drafts that commenced in 1863, some objectors were able to avoid military service for physical and medical issues.

If ”held to service” under the draft, the most common method of obtaining exemption was to pay the $300 commutation fee; however, some did provide substitutes. Later in the war, service in military hospitals — usually in Philadelphia or Washington, D.C. — was offered as an option, but few objectors accepted it.

In their book, “Mennonites, Amish and the American Civil War,” Mennonite historians Steve Nolt and James Lehman reported that they found no direct evidence of such noncombatant service. In my 40 years of research, I uncovered references to maybe two or three men who did so.

Q. Your extensive family research has shown that none of your direct family wore a uniform in the Civil War. Did your family members – and conscientious objectors in Pennsylvania – generally suffer from criticism for choosing not to serve.

A. Neither my family, nor Civil War conscientious objectors in Pennsylvania in general, suffered much for taking the stand that they did. The Historic Peace Churches have a long history in the Commonwealth, so their neighbors and communities would have been familiar with them and their beliefs, to some extent.

During the Civil War, the Peace Churches tended to support the Republican party, which made their support valuable at both the state and federal levels with executives of that party in office. On occasion, the newspapers of the era took the objectors to task, but I have seen little evidence of real physical persecution or violence against them.

The draft officials found them to be problematic at times because they posed situations that required finer interpretations of the draft laws and regulations, but religious objectors did not concern those officials as much as individuals and groups who were violently opposing the draft.

In central Pennsylvania, an interesting question involving “conscientious men” came up: May a man claim to be an objector and pay the commutation fee if he joined a Peace Church after his name was pulled from the draft wheel? One draft district allowed as such, another did not, causing some confusion in the draft bureaucracy.

Q. The use of “affirmation” rather than “swearing” in court or in oaths for public office takes us back to the days of the Quakers. Are there other parts of the conscientious objectors’ story in 21st-century wars or that we would recognize today in American life?

A. Probably the most interesting carry-over of the peace tradition in Pennsylvania is the statement in Article II, Section 16 of Pennsylvania’s current Constitution that states: “The General Assembly . . . may exempt from State military service persons having conscientious scruples against bearing arms.”

Appearing in language regarding the National Guard, this, however, does not apply to military service in the federal forces; yet, it is an intriguing nod to our Commonwealth’s rich religious history.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Religious objectors in York County and PA history

money

money