As protests continue over police killings, lawmakers try to add to the list of crimes protesters could face

After weeks of Black Lives Matter protests last summer, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis decided he'd seen enough of agitators, as he called them, who were "bent on sowing disorder and causing mayhem."

There had been at least 79 demonstrations in Florida in the two months since George Floyd had died in Minneapolis, including some that turned violent. Amid a citywide curfew in Tampa, protesters traded rocks, bottles and glass for pepper spray and rubber bullets from law enforcement. At least one protester was hit in the head by a rubber bullet.

DeSantis, flanked by uniformed law enforcement officials and Republican lawmakers, announced a new legislative priority: a law to ban loosely defined "violent or disorderly assemblies" and punish efforts to defund the police.

A version of that bill awaits DeSantis' signature after passing the Legislature Thursday.

Florida was at the beginning of a wave of bills across the country after millions hit the streets to protest police brutality and racial discrimination in the wake of Floyd's death.

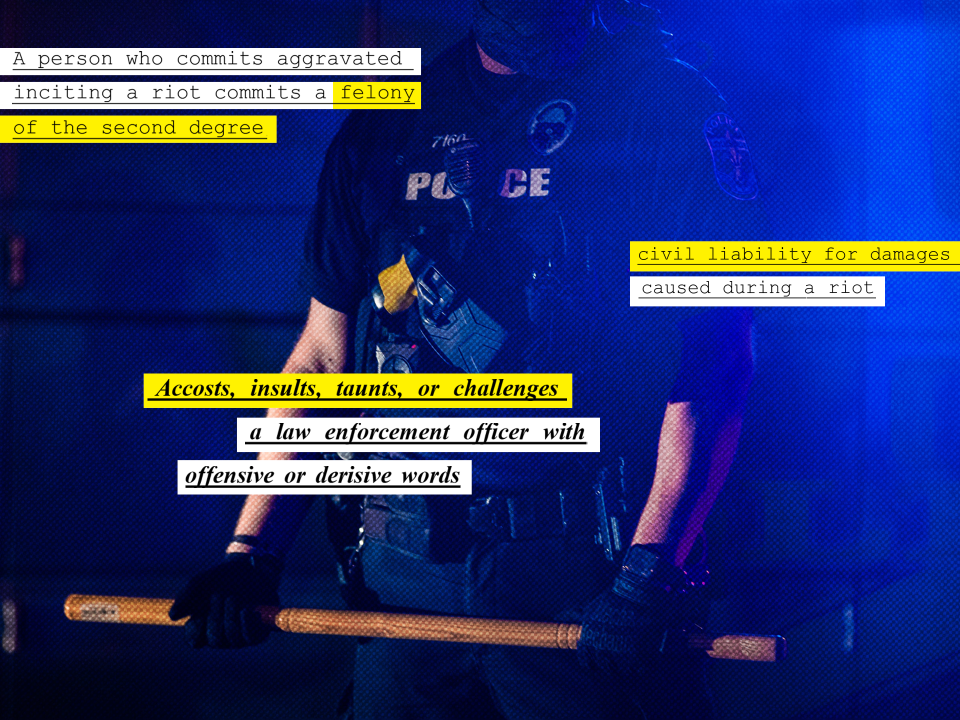

At least 93 similar bills have been proposed in 35 states since Floyd died under the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin last May. The bills would ban “taunting police” and “camping” on state property, expand activities that are illegal during a riot and impose harsher penalties for blocking traffic.

“These bills talk about ‘riots,’ but the language that they use is so sweeping that it encompasses way more than what people imagine,” said Elly Page, a senior legal adviser with the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law.

The bills, she said, would criminalize “peaceful, legitimate First Amendment-protected protest.”

'We will not stop until there is justice': More than a thousand in Chicago gather to remember Adam Toledo, boy killed in police shooting

As a jury in Minneapolis is set to begin deliberations Monday in Chauvin's murder trial, cities are preparing for the possibility of more protests. People took to the streets in nearby Brooklyn Center to protest the fatal shooting of Daunte Wright and in Chicago over the killing of 13-year-old Adam Toledo.

In Oklahoma, a bill that would give drivers legal protection for unintentionally hitting a protester "while fleeing a riot" was sent to the governor Thursday. Protesters who block streets, highways or vehicles would be liable for any damage or injuries, and they could face penalties of up to a year in jail.

Bills in other states, such as Iowa, have similar provisions. Last summer, there were more than 100 incidents in which people drove cars into crowds of demonstrators.

More than a dozen bills would allow local governments to be held financially liable for damages if they fail to control protests that get out of hand.

Some bills would add potential penalties for governments that "defund" their police departments – a movement that arose after Floyd's death – by substituting social services for certain police actions.

Many of the bills will never be enacted, Page said, but the political climate favors them in Arizona, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri and Oklahoma.

Bills in Arizona, Indiana, Minnesota and Oregon would strip public assistance, such as food stamps, welfare and unemployment compensation, from people convicted of participating in a riot or inciting one.

"It's so devious, selectively silencing people," Page said. "This is the kind of penalty that really impacts certain communities and not others."

A time of historic protests

Fifteen million to 26 million people protested Floyd's death last summer, according to the Crowd Counting Consortium. That would make it among the largest protest movements in U.S. history, if not the largest.

Marcus Anthony Hunter, a professor of sociology and African American studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, said the demonstrations were unprecedented as much for their diversity as their size.

"It is the largest assembly of non-Black people demanding justice for Black people I have ever seen in this country," Hunter said. "Young, old, poor, immigrant, women, men, trans, gay people."

See where they marched: Tracking protests across the USA in the wake of George Floyd's death

Many of those protesters were arrested. In thousands of cases, their charges were dropped because they were exercising their First Amendment rights and hadn't engaged in violence or damaged property.

Police commonly declare an "unlawful assembly" to clear an area, arresting people who refuse to disperse or break curfew – even if they haven't committed other crimes.

Of the 521 misdemeanor cases brought to the Minneapolis city attorney’s office over two weeks of protests after Floyd’s death, 489 were dismissed, said Mary Ellen Heng, deputy city attorney of the office’s criminal division.

The office dropped charges “if we felt that the only action of the individual was being out after the imposed curfew, but otherwise they were part of a peaceful assembly (and) failed to disperse,” Heng said.

The office pursued cases in which the defendant was charged with another crime, such as fleeing police, damaging property, driving while intoxicated or having an unlicensed gun.

The many bills introduced in the past 10 months represent an acceleration of a trend that began under the Trump administration. Nearly all of the bills introduced since Floyd's death have been sponsored by Republicans, according to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, which tracks the initiatives.

Florida bill expands definition of a riot

Florida's so-called anti-riot bill became a sort of model for measures across the nation.

Known as Measure HB 1 – a sign of its high priority for lawmakers – it may have been the most divisive bill to face lawmakers this session. Proponents argue the bill is necessary to protect businesses and communities from the violence of the mob. Opponents called it a racially tinged attack on free speech.

The measure would toughen penalties for several crimes and create criminal charges such as “mob intimidation,” “inciting a riot” and “defacing, damaging or destroying a monument.” The last provision is largely aimed at protecting Confederate statues.

State Rep. Cord Byrd, R-Neptune Beach, told Florida lawmakers on the House floor last month that the “First Amendment does not protect violence; it also does not protect fighting words” or words that stir a panic.

“We can act before it’s too late. We don’t need to have Miami or Orlando or Jacksonville become Kenosha or Seattle or Portland,” Byrd said, referring to some of the cities that saw violence last summer.

The bill would revise the definition of a riot to a gathering in which three or more people collectively intend to engage in disorderly conduct and participate in a "violent public disturbance" ending in property damage, injury or creating a danger of either.

"With that definition, you could see how someone could be charged with a riot without doing anything violent or destructive," Page said. "You just have to be in a group where somebody might be doing something threatening to be violent or destructive."

The bill would create a charge called "aggravated rioting," which would carry a penalty of up to 15 years in prison.

Rachel Gilmer, co-director of Dream Defenders, a youth organization founded after the killing of Trayvon Martin, said there were protests in at least a third of the state's 67 counties last summer, including in rural areas not known for demonstrating against racial injustice.

Gilmer said it was no coincidence that DeSantis called for a bill "meant to repress and censor our movements" because the state is "ground zero" for the Black Lives Matter movement.

Iowa: ‘Violence and anarchy’ are unacceptable

Floyd's death spurred Iowa lawmakers to come together to ban most police chokeholds and bolster training, among other efforts. This year's proposals have been more polarizing.

At the request of Gov. Kim Reynolds, her fellow Republicans in the Legislature advanced a measure that would enhance the penalties for rioting, criminal mischief and disorderly conduct. Similar bills are pending.

"Violence and anarchy is not acceptable," Reynolds said in calling for the bill. She pointed to last summer's civil unrest around protests in Des Moines and other Iowa cities, the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 and an incident in Davenport in June, when after a night of unrest, an officer was shot during an ambush and multiple shootings left people dead.

“The bill will make it clear that if you riot or attack our men and women in uniform, you will be punished,” Reynolds said. “We won’t stand for it.”

The American Civil Liberties Union and Iowa-Nebraska NAACP oppose the proposal. Democrats criticized the increased penalties as too severe.

The Republican-controlled House and Senate passed versions of this bill, making it likely to become law.

Rioting would become a felony and unlawful assembly an aggravated misdemeanor. People present during a riot could be charged with felony disorderly conduct. Defacing public property would be a felony.

The bill would make it a crime to intentionally point a laser at a police officer "to cause pain or injury."

Kentucky lawmakers considered making cities liable for damaging riots

In Kentucky, a bill would have made it a crime to insult or taunt an officer during a riot with words “that would have a direct tendency to provoke a violent response from the perspective of a reasonable and prudent person."

The bill failed to move forward before the Legislature's session ended. If it had passed, offenders could be charged with disorderly conduct, a misdemeanor with a penalty of up to 90 days of imprisonment.

The wide-ranging bill was sponsored by state Sen. Danny Carroll, a Republican and a retired police officer who represents Paducah. He said the bill was a response to those who "tried to destroy the city of Louisville" in what he called "riots" last year.

The fatal police shooting of Breonna Taylor in Louisville led to months of clashes between police and protesters and 871 protest-related arrests, including 252 for at least one felony charge, from late May through late September.

Many of those people were charged under the state's riot statute and other "trumped up" charges, most of which were dismissed, Randy Strobo, an attorney with the Louisville law firm Strobo Barkley, said in an email.

Carroll's measure included a provision noting that if elected officials have reason to believe there is going to be a riot and they are grossly negligent in their response, they could be held liable for the riot and any property damage.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Opponents said the bill would have incentivized local governments to be more aggressive against protesters.

Lane Boldman, executive director of the nonprofit Kentucky Conservation Committee, said Carroll failed to understand the "unintended consequences" of his bill.

"How do you define a riot? How do you define when someone is being aggressive or insulting in a way that provokes a riot?" Boldman asked. "Officers, they have to put up with a lot. They are usually in situations where tempers are heightened for both the citizen and the officer. So you have to be clear about your definitions and reduce the situations that allow it to be subjective."

The bill was derided by the ACLU of Kentucky and Democrats as an attack on the First Amendment. Democratic state Sen. Gerald Neal called it a “backhand slap” against his majority-Black district in Louisville.

Tennessee: 'We are talking about activity that becomes violent'

Months after hundreds of protesters gathered last summer near the state Capitol in Nashville after the deaths of Floyd and Taylor, state Sen. Mike Bell of Riceville introduced one of two bills filed by Tennessee Republicans seeking to enhance penalties for riot-related crimes.

Bell said he filed his bill largely in response to last summer’s movement. Although the protests in Nashville were mostly peaceful, there were incidents of vandalism and arson, such as when protesters started a fire at Nashville's Metro Courthouse.

Bell said he's not targeting protests where people want to "express their grievances. ... We are talking about activity that becomes violent, activity that destroys property.”

Under law, Tennesseans who knowingly participate in a riot that results in property damage or injury can be convicted for aggravated rioting, a felony. Bell’s bill would mandate 45 days in jail for people who travel from out of state to a riot and intend to commit a crime.

The bill passed the state Senate mostly along party lines in March and awaits further action in House committees.

Another bill would make it a crime to intimidate or harass someone during a riot and to throw something at someone with the intent to harm them. The bill has yet to arrive in any committee in the Senate and has not made it to the House floor.

Minnesota bills lack traction

In response to protests over the Keystone XL pipeline, lawmakers in Minnesota have tried for the past few years to pass a law to increase penalties for blocking traffic. They tried again after Floyd's death.

Republican state Rep. Paul Novotny of Elk River, who worked in law enforcement for more than three decades, is the primary sponsor of a bill that would increase penalties for obstructing traffic on freeways and access to airports. Those would be more serious misdemeanors punishable by up to a year of imprisonment and a $3,000 fine.

Black Lives Matter protesters have blocked major Twin Cities interstates. Some demonstrations devolved into looting and serious property damage.

"It's not a surprise to see some of these bills be introduced again," said Julia Decker, policy director for the ACLU of Minnesota. She said the civil liberties organization opposes "any bill that's going to criminalize First Amendment-protected speech rights and associated rights."

Having only Republican support in the split Legislature – and Democratic Gov. Tim Walz empowered with a veto – the bill is unlikely to gain traction.

A bill from Republican state Rep. Eric Lucero, a cybersecurity specialist, would withhold state loans, grants or other public assistance from people convicted of any offenses tied to protests, demonstrations, rallies, civil unrest or marches. The bill has no co-sponsors and has not progressed since it was introduced in January.

Contributing: John Kennedy, USA TODAY Network-Florida Capital Bureau; Joe Sonka, The Courier-Journal; Yue Stella Yu, The Tennessean; Nora Hertel, St. Cloud Times; Ian Richardson, Des Moines Register

Follow Tami Abdollah, a national correspondent covering criminal justice, on Twitter at @latams.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: BLM protests spur 'anti-riot' bills to expand list of crimes

money

money