Pandemic first graders are way behind in reading. Experts say they may take years to catch up.

AUSTIN, Texas – Most years, by the third week of first grade, Heather Miller is working with her class on writing the beginning, middle and end of simple words. This year, she had to backtrack – all the way to the letter “H.”

“Do we start at the bottom, or do we start at the top?” Miller asked in front of her class at Doss Elementary.

“Top!” chorused a few voices.

“When I do an H, I do a straight line down, another straight line down, and then I cross in the middle,” Miller said, demonstrating on a projector in a front corner of her classroom.

Her 25 students set to work on their own. Some got it right away. One student watched his tablemate before slowly copying down his own H’s. Another tested her own way of writing the letter: one line down, cross in the middle, then another line down. “Your paper is upside down, let’s turn it,” Miller said to a student who was trying to write letters while leaning sideways, almost out of her seat.

The first months of school this fall have laid bare what many in education feared: Students are way behind in skills they should have mastered.

Children in early elementary school have had their most formative first few years of education disrupted by the pandemic, years when they learn basic math and reading skills and important social-emotional skills, like how to get along with peers and follow routines in a classroom.

Though experts said it’s likely these students will catch up in many skills, the stakes are especially high around reading. Research shows if children are struggling to read at the end of first grade, they are likely to still be struggling as fourth graders. In many states with third grade reading “gates” in place, students could be at risk of getting held back.

Learning to read during COVID-19: Students struggled. Expectations didn't change.

‘The reading year’

First grade – “the reading year,” as Miller calls it – is pivotal for elementary students. Kindergarten focuses on easing children from a variety of educational backgrounds – or none at all – into formal schooling. First grade concentrates on moving students from pre-reading skills and simple math, such as counting, to more complex skills, such as reading and writing sentences and adding and subtracting numbers.

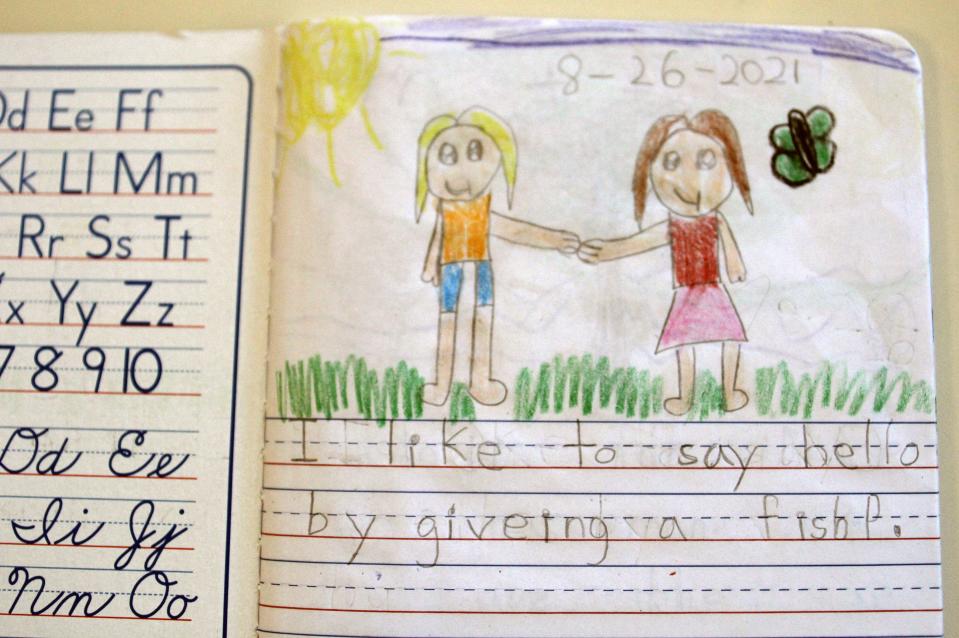

By the end of first grade in Texas, students are expected to be able to mentally add or subtract 10 from any given two-digit number, retell stories using key details and write narratives that sequence events. The benchmarks are similar to those used in the more than 40 states that, along with the District of Columbia, adopted the national Common Core standards a decade ago.

“They really grow as readers in first grade and writers,” Miller said. “It’s where they build their confidence in their fluency.”

About half of Miller’s class of first graders at Doss Elementary, a spacious, bright, newly built school in northwest Austin, spent kindergarten online. Some were among the tens of thousands of children who sat out kindergarten entirely last year.

More than a month into this school year, Miller found she was spending extensive time on social lessons she used to teach in kindergarten, such as sharing and problem solving. She stopped class repeatedly to mediate disagreements. Finally, she resorted to an activity she used to do in kindergarten: role-playing social scenarios, such as what to do if someone accidentally trips you.

2021: A wild ride. Let’s get through it together with Keeping It Together, a newsletter of tips, memories and small pieces of joy amid this crazy world.

“So many kids are missing that piece from last year because they were, you know, virtual or on an iPad for most of the time,” Miller said.

Her students were not as independent as they had been in previous years. Used to working on tablets or laptops for much of their day, many students were behind in fine motor skills, struggling to use scissors and correctly write numbers.

Instead of working on first grade standards, Miller was devoting time on this Friday morning in early September to forming upper- and lowercase letters, a kindergarten standard in Texas and the majority of other states. As students finished practicing the letter H, they moved on to the assignment at the bottom of the page: Draw a picture and write a word describing something that starts with an H.

“H-r-o-s” one student wrote next to a picture of a horse standing on green grass in front of a light blue sky. “H-e-a-r-s” another student wrote next to a picture of a strip of brown hair, floating in the white picture box. “You should draw a face there,” his tablemate suggested, pointing at the blank space under the hair.

Miller’s first graders are a case study in the depth of learning loss during the pandemic. One report by Amplify Education, which creates curriculum, assessment and intervention products, found children in first and second grade experienced dramatic drops in grade-level reading scores compared with those in previous years.

In 2020, 40% of first grade students and 35% of second grade students scored “well below grade level” on a reading assessment, compared with 27% and 29% the previous year. .

Data analyzed late last year by McKinsey, a management consulting firm, concluded children have lost at least one and a half months of reading. Other data shows low-income, Black and Hispanic students are falling further behind than their white peers, worsening achievement gaps.

Which students missed class during COVID-19? We asked, and schools don’t know

“Higher-income parents, higher-educated parents, are likely to have worked with their children to teach them to read and basic numbers, and some of those really basic, early foundational skills that kids generally get in pre-K, kindergarten and first grade,” said Melissa Clearfield, a professor of psychology who focuses on young children and poverty at Whitman College. “Families who were not able to, either because their parents were essential workers or children whose parents are significantly low-income or not educated, they’re going to be really far behind.”

‘Diversity in skills’

What Miller observed in the first few weeks of the school year is probably taking place in classrooms nationwide, experts said. In April, researchers with the nonprofit NWEA, which develops school assessments, predicted how the pandemic’s disruptions would manifest among the kindergarten class of 2021: a wider range of ability levels; large class sizes with more diverse ages because some parents held children back a grade; and students unfamiliar with in-person classroom routines.

“We predicted that there would be a lot of diversity in skills,” said Brooke Mabry, strategic content design coordinator for NWEA Professional Learning. That includes academics, social-emotional skills and executive functioning – which includes self-control, following directions and thinking flexibly.

Though switching to remote learning was hard on many students, younger students were generally unable to log themselves on to a computer independently and focus on virtual lessons for extended periods of time. Teachers, who usually rely on small, in-person groups for early literacy skills, had to teach letters, sounds and sight words via online platforms.

Miller had the unwieldy task of teaching kids both in person and online, spending her year pivoting between students in front of her and students on her computer screen, using her projector to display books to students at home and teaching reading skills via virtual groups.

Once students were in front of her again, Miller found that online lessons weren’t as useful as many had hoped.

Teachers are exhausted, 'stretched too thin': Schools cancel class or return to remote learning

Miller, 30, is a calm, confident teacher who is in her eighth year of teaching and her second at Doss. She usually has students with a wide range of ability levels at the beginning of the year. Nearly 62% of students at the school are white, and fewer than 20% are economically disadvantaged, compared with the district average of nearly 53%. In 2019, 95% of Doss’ students passed the state reading assessment.

This year, Miller saw larger gaps in reading skills than ever before. Usually, her first graders would start with reading levels ranging from mid-kindergarten to second grade. This year, the levels spanned early kindergarten up to fourth grade.

“My kids are so spread out in their needs,” Miller said. “I just feel like – and I’m sure every teacher feels like this – there’s so much to teach, and somehow there’s not enough time.”

She’s seen higher literacy levels for kids who went to school in person last year. To her, it speaks to the immense benefits kids get from all aspects of in-person learning. “It just shows how important it is for these kids to be around their peers and just have normalcy,” she said.

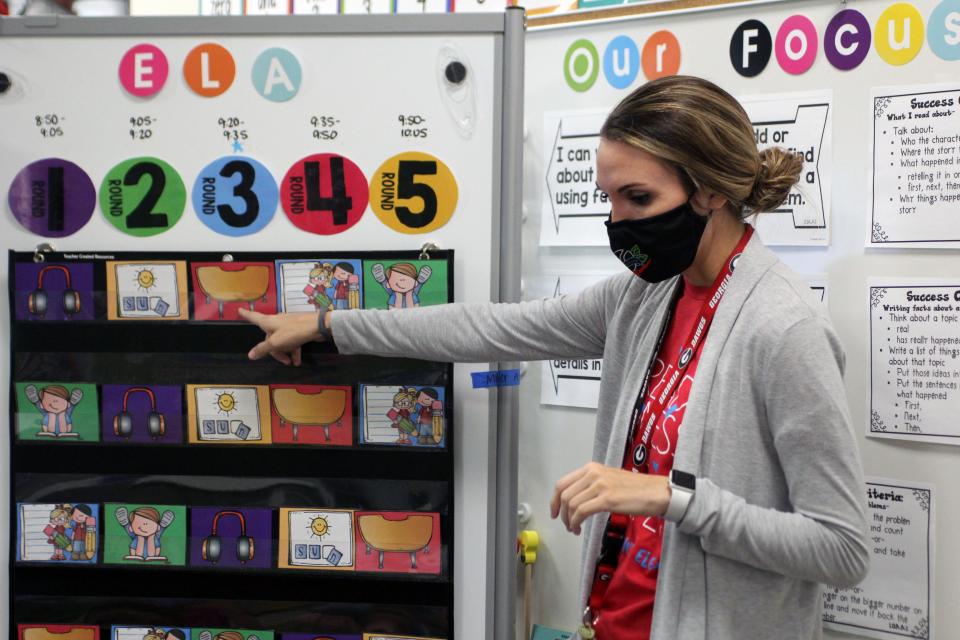

To catch kids up, Miller relies on, among other things, one of the staples of the early elementary classroom: center time. For two hours a day, she works with small groups of students on the specific math and reading skills they lack.

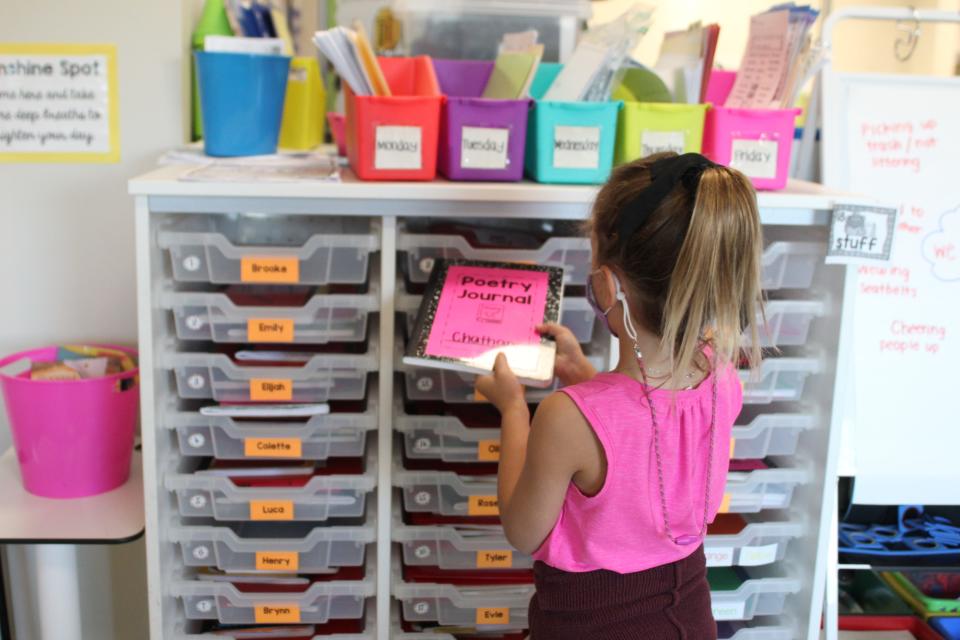

In October, Miller divided her class into five groups to rotate through activities around her room. She gave her students a few minutes to finish a writing assignment as she pulled out several sets of small books at various reading levels; colorful plastic, hollow phones so her students could hear themselves read; and for a group of struggling readers, a matching game featuring cards showing letters and pictures.

“I feel like I’m teaching four grades,” Miller said as she arranged the materials on her desk.

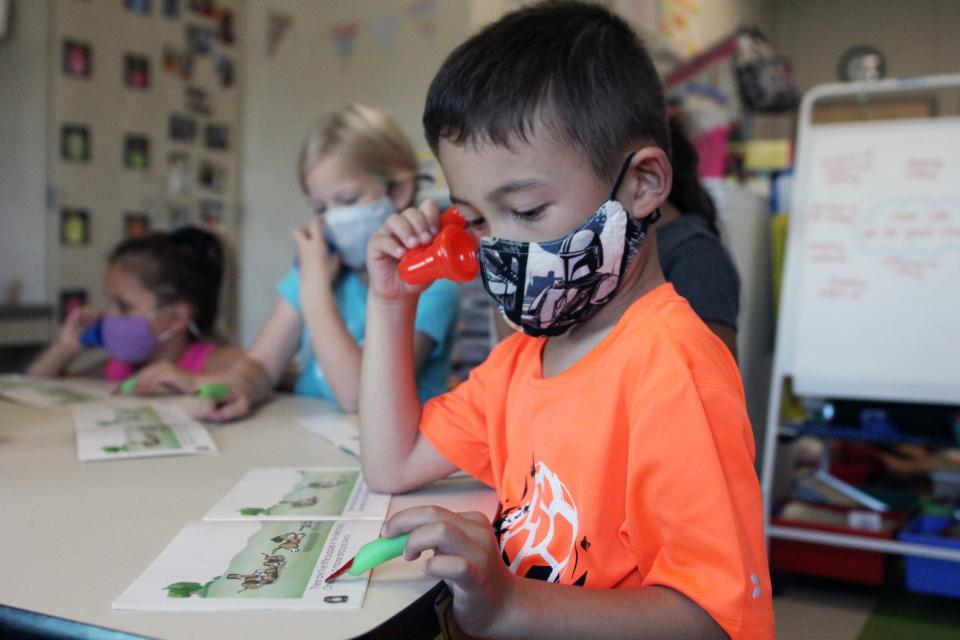

Several minutes later, seated at a table in the back of the room with five of her students who read at a first grade level, Miller handed them each a phone, a small book and a green witch’s finger to help them point at the words in the book. “Today we’re going to talk about our reading tools,” Miller said, holding up a blue plastic phone. “These are called whisper phones. You whisper so you can hear yourself sound out the words. Do these go on our heads?”

“No!” the students said, giggling.

“You know what these are for?” she said, holding up a rubber finger.

“Um, they’re for reading,” one student said. “’Cause I had them in kindergarten.”

“Very good. Are these for picking your nose?” Miller asked.

“No!” the students said, laughing.

She placed a book in front of each child and walked them through a series of exercises, including looking at the cover and predicting what the book would be about.

They opened their books and began to read in a whisper, pointing at each word with their green rubber fingers.

Don’t be ‘frantic’

Miller’s next group, all of whom were reading far below first grade level, required a different activity. Miller pulled out the letter-matching game, left over from her days as a kindergarten teacher. She placed two small laminated cards on the table, one showing the letter D and a picture of a dog and one with the letter B and a picture of a ball.

“We’re going to do your letters today,” Miller told the group. “What letter is this?” she asked, pointing to the B.

“Ball!” one student responded.

“What letter?” Miller asked again. There was a pause.

“B!” another student responded.

“What sound does it make?”

“Buh,” a third student said.

Despite the need to catch kids up, Miller has been mindful of not coming on too strong with remediation efforts. “I don’t want to push them so hard where they get burned out,” she said. “They’ve been through so much.”

Society needs to view the recovery process as a multiyear effort, said Mabry of NWEA. “In previous years, when looking at unfinished learning ... we never expected that we would get students who need support to meet those accelerated goals in one year. … Now, we’re so frantic.”

It's a daunting task, but experts said there is hope.

“Kids will catch up eventually,” said Clearfield from Whitman College. But to get there, society may need to reevaluate expectations.

Schools got record money under COVID-19 relief: Will it help kids who need it most?

“If most children in our community are behind by, like, a year or two, then our expectations for what is typical, it’s going to have to match where they are,” Clearfield said. “Otherwise, we are going to be constantly frustrated. … We’re going to have expectations that don’t match their skills or abilities.”

By mid-autumn, Miller was heartened by what she saw in her classroom. Students became more confident and independent. Their writing was stronger. There were fewer conflicts.

One morning, Miller stood by her desk as students effortlessly transitioned from one activity to the next during center time. They quietly buzzed around, cleaning up activities and putting their notebooks away in cubbies as she prepared to work with a new group of students.

“It kind of gives me hope that we’ll be OK,” she said. “Even after last year, we’ll be OK.”

This story about reading skills was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Pandemic disrupted how kids learn to read, teachers say

money

money