Native Americans in Chicago have high opioid death rates. So why won't they get tribal settlement money?

CHICAGO – Sarina DiMaso, a citizen of the Chiricahua Apache and Taino Nations, stumbled into her Chicago home seven years ago after a drug and alcohol binge to find her 24-year-old daughter, Nicole, dead by suicide in DiMaso’s bedroom.

Riddled with guilt and trapped in a decades-long battle with an opioid addiction, DiMaso carried her daughter’s ashes in the passenger seat of her truck for two years, until a near-fatal crash into a tree convinced her to seek treatment.

“I woke with bruises, bumps and my daughter’s ashes all over me,” DiMaso said. “I really felt like, wow, my daughter saved my life. That’s when I crawled out onto the ground, still inebriated at the time, and I asked my Creator to please help me with my drinking and drugging, my opioid addiction.”

DiMaso, 50, is one of many Native American Chicagoans ensnared in the opioid epidemic, which has led to disproportionately high addiction and death rates in Native communities nationwide.

More than 400 tribes and tribal organizations agreed to a tentative $590 million settlement with Johnson & Johnson and the country’s three largest drug distributors – McKesson, AmerisourceBergen and Cardinal Health – in early February after they accused the companies of overwhelming their communities with highly addictive opioids.

But Indigenous leaders in Chicago – home to the third-largest urban Native American population in the country, with more than 65,000 people representing 175 tribes – do not expect to receive any of that money because of the absence of tribal land in Illinois. It's part of a larger problem that keeps urban Natives from receiving support for issues just as pervasive in cities as on reservations.

“Nope, we'll probably never see it,” Melodi Serna, executive director of the American Indian Center of Chicago, said of the settlement money. “Do we still face the same opioid crisis that Indian Country does? Absolutely.”

Urban Natives struggle to obtain funding

Serna, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and the Oneida Nation, said because neither Chicago nor Illinois is home to any tribes or reservations, the city’s Native community has long struggled to tap into the limited federal funding for American Indians.

“Tribal funding doesn't come to us even though we serve (a population) sometimes larger than most tribal nations,” Serna said. “The federal government isn't really recognizing urban Natives and the work that we do, so, you know, financially, that puts us in a really, really tricky place.”

Voting: For some Native Americans, casting a ballot means an 'absurd' trip to the polling site

Chicago is located on the ancestral homelands of the Council of the Three Fires: the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi Nations. Today, the city is home to citizens of nearly 200 tribes, many of whom were incentivized by the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 to leave their lands and assimilate into U.S. society.

About 70% of American Indians and Alaska Natives now reside in urban or suburban areas, according to the Indian Health Service, but just over 1% of the $8.5 billion IHS budget goes to urban Indian health care organizations, known as UIOs.

According to the National Council of Urban Indian Health, which represents the 41 UIOs across the country, most rely on grants and other supplemental funding sources to provide essential care.

Generational trauma

Now nearly three years into her recovery, DiMaso is a behavioral health counselor who provides relapse, recovery and suicide prevention treatment at the American Indian Health Service of Chicago, the city’s only UIO.

U.S. opioid overdose deaths soared to a record high of 75,000 in 2021, with the rate of deaths among American Indians and Alaska Natives exceeding the national average every year since 2000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

American Indians and Alaska Natives had the highest drug overdose death rates of any racial or ethnic group in 2020: 42.5 deaths per 100,000 people, compared with 28.3 deaths per 100,000 people for the overall U.S. population.

The CDC notes that Native Americans are often misclassified as a different ethnicity, which likely means their death rate is underestimated.

More: Native Americans die younger, CDC study shows. They say it's proof of 'ongoing systemic harm.'

“What I tell my clients is, we carry intergenerational trauma from three generations before,” DiMaso said. “So your great, great, great, great grandmother, whatever was going on with her, you carry that now because blood remembers.”

Epigenetic trauma – the idea that trauma can permanently alter DNA across multiple generations – is pervasive in groups with a history of oppression or genocide, including Native Americans, said Dr. Albert Mensah, medical director of the American Indian Health Service of Chicago.

While trauma does not damage or mutate genes, it has been found to leave a chemical mark that can change a gene’s expression.

Though he rarely prescribes opioids, Mensah regularly treats patients with chronic pain conditions, some of whom use opioids for pain management. He said at least 30% of AIHSC patients seek treatment for substance abuse issues.

“Some of these pain syndromes, quite literally, are more of an epigenetic nature,” Mensah said. “They are inherited susceptibilities to trauma, emotional or otherwise, and many people are on these medications for numbing purposes to deal with emotional turmoil.”

Such problems, he said, are often exacerbated by the stressors of an urban setting like Chicago, where more than 1,800 residents died of drug overdoses in 2020, according to the Cook County Department of Public Health.

'Still killing us': The federal government underfunded health care for Indigenous people for centuries. Now they're dying of COVID-19

“They've got a new environmental stress that's present 24/7, and the natural proclivity is to try to appease that by manipulating the environment around them [through] food or drugs or alcohol,” Mensah said.

Today, DiMaso is walking what the Native community calls the “Red Road,” a healthy balance between the mental, physical, emotional and spiritual self. But she is one of the few Indigenous counselors leading her community down that same path with culturally competent care.

“They're doing it on such a minute level,” Serna said of urban Native American counselors like DiMaso, “because we're being left out of a larger conversation and the larger funding to provide that resource for our community.”

Settlement allocations still to come

Each of the 574 federally recognized tribes will be eligible to sign onto the opioid settlement deal, even if they did not participate in the lawsuit. Tribes and appointed tribal leaders will then decide how to disburse the money they receive over seven years, said Lloyd Miller, a lawyer who represented the tribes in the lawsuit.

“The dollars are big, but the need is so much bigger,” Miller told USA TODAY. “Standing alone, the money is not sufficient, not close to sufficient.”

University of Chicago law professor Todd Henderson, who led the school’s first Native American law program, said urban organizations often get overlooked when the federal government or other entities disburse funds. He expects a similar outcome with the settlement money.

“You end up with this kind of paradox where you might actually have more Native people living in Chicago, by a large amount, than living on a small reservation in Wisconsin,” he said. “Yet, that small reservation in Wisconsin is getting the money, and the Native people here in Chicago, who may have been impacted by the opioid crisis, are not seeing it.”

More: Tribes were often overlooked in COVID-19 vaccine trials, frustrating Indigenous leaders

Extending resources to all

Heather Tanana, a law professor at the University of Utah and citizen of the Navajo Nation, anticipates most tribes will use their settlement money to improve addiction treatment programs on reservations.

Recent expansions in telehealth amid the COVID-19 pandemic could extend access to those living off-reservation as well, she said.

“When these tribes get this settlement money and they're putting it into their opioid treatment programs … it could reach all of their tribal members, regardless of where they live,” Tanana said, “if they plan the program in that way, incorporating telehealth components.”

But Chicago’s Native American leaders say their funding struggles extend far beyond the money they could receive from the opioid settlement.

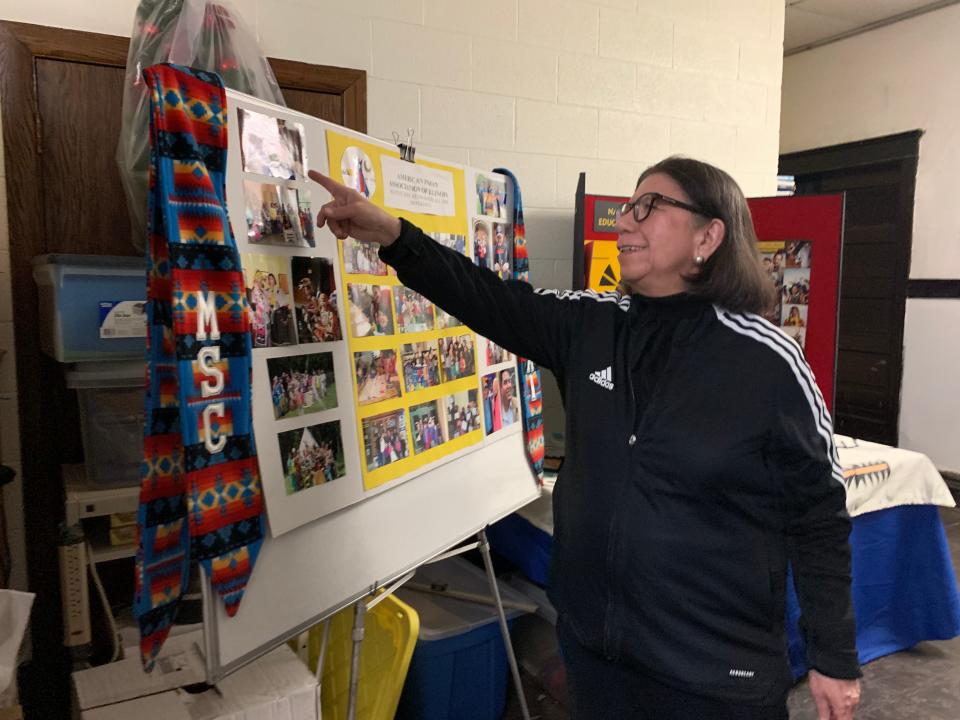

Dorene Wiese, president of the Chicago-based American Indian Association of Illinois, said the fundamental issue is a lack of awareness that their community even exists in the city – part of a nationwide problem with federal data collection that often undercounts or mislabels Native Americans.

The Native community nicknamed itself the “Asterisk Nation,” she said, because an asterisk is sometimes used in place of a data point to explain inaccuracies in their ethnicity data. At face value, the asterisk is a caveat for small sample size and large margins of error, but Wiese said she sees it as a symbol of her community’s invisibility in the eyes of lawmakers.

“The language everywhere has to include the word ‘urban’ – urban Indian or urban Native,” said Wiese, a citizen of the Minnesota White Earth band of Ojibwe Indians. “They have to say it, they have to write it and then it'll reach a critical mass, eventually. Because they don't get it, you know. We’re just invisible.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Opioids: Native Americans in Chicago lost out on funding

money

money