NASA's DART spacecraft crashing into an asteroid could one day save humanity

More than 6.5 million miles away from Earth, a cosmic collision is imminent.

In a first-of-its-kind maneuver, a NASA spacecraft is set to intentionally smash into an asteroid to test whether deflecting a space rock could one day protect Earth from a potentially catastrophic impact.

The crash is planned for 7:14 p.m. ET Monday. Live coverage will air on NASA TV beginning at 6 p.m. ET.

The mission, known as DART, or the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, will attempt a method of planetary defense that could save Earth from an asteroid on a potential collision course with the planet. It's a rare opportunity to conduct a real-world experiment on an asteroid that doesn't pose a threat to Earth, said Bruce Betts, the chief scientist at the Planetary Society, a nonprofit organization that conducts research, advocacy and outreach to promote space exploration.

Betts called the DART mission "a big step forward for humanity," saying it will not only help scientists assess one of the most popular ideas for planetary defense but also provide an exciting way to raise awareness about the need to plan ahead for such circumstances.

"The thing that makes this natural disaster different is that if we do our homework, we can actually prevent it," he said. "That's a huge difference compared to a lot of other large-scale natural disasters."

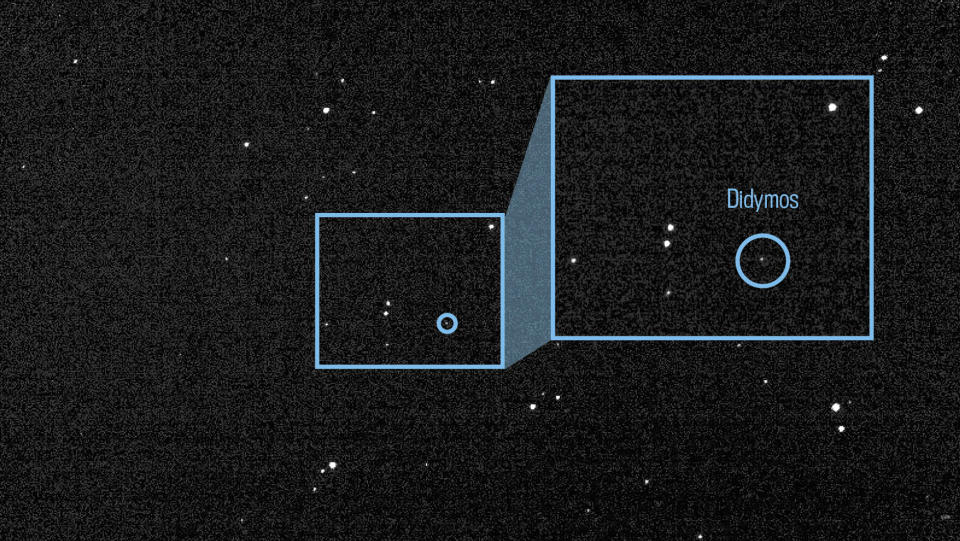

The DART probe's target is a space rock called Dimorphos, which measures 525 feet across and orbits a much larger, 2,500-foot-wide asteroid named Didymos.

On Monday, the spacecraft will crash into Dimorphos at a blistering speed of around 4 miles per second, or 15,000 mph. The goal isn't to obliterate the asteroid but rather to see whether the collision can alter the space rock's nearly 12-hour orbit.

In a real-life planetary defense situation, even a relatively small nudge could change an asteroid's orbit enough to keep Earth in the clear, Betts said.

"It depends on the size of the object and how much warning time you have, but you do, indeed, just need to change the orbit a little bit," he said.

The DART probe, which is about the size of a small car, will be destroyed in the maneuver, but a small, Italian-built cubesat that was deployed as part of the mission will be able to assess the immediate aftermath.

The tiny satellite, known as LICIACube, will fly within 25 to 50 miles of Dimorphos a few minutes after the crash, Dan Lubey, the LICIACube navigation lead at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement — "close enough to get good images of the impact and ejecta plume, but not so close LICIACube could be hit by ejecta."

Ground-based telescopes will be used to time Dimorphos' orbit and determine whether the mission was a success. A follow-up expedition developed by the European Space Agency will study the impact crater on Dimorphos and conduct more detailed investigations of the asteroid system. That mission, known as Hera, is scheduled to launch in 2024.

"We want to know what happened to Dimorphos, but more important, we want to understand what that means for potentially applying this technique in the future," Nancy Chabot, the DART coordination lead at Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory, said in a news briefing this month. The Applied Physics Lab built and manages the $325 million DART mission for NASA.

No known asteroid larger than 450 feet across has a significant chance of smashing into the planet in the next 100 years, according to NASA, but the agency has said only a fraction of smaller near-Earth objects have been found.

The agency's Planetary Defense Coordination Office is involved with searching for near-Earth objects that could be hazardous to the planet, including those that venture within 5 million miles of Earth's orbit, and objects large enough to cause significant damage if they hit the surface.

Even if the DART mission fails, scientists will learn a lot from the experiment, said Andrea Riley, a program executive in NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

"If it misses, it still provides a lot of data," Riley said in the news briefing. "This is why we test. We want to do it now rather than when there is an actual need."

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

money

money