How a 'narco-plane' expert headed off a major cartel drug shipment into the US

ORLANDO, Fla. ― A Mexican cartel associate sneaked into the U.S. and headed to Florida to buy a private jet intended to haul more than $75 million worth of cocaine out of the South American jungle.

The plan was for the drugs to be divided up in Mexico and sent across the border, largely on semi trucks destined for several U.S. cities.

But something unexpected happened in Sanford, Florida ― 43 miles northeast of Disney World.

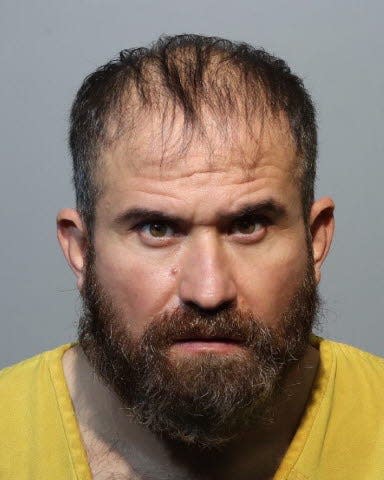

The cartel associate, Jesus Emanuel Pimentel Enriquez, 41, and his partner in crime, a Texas-based airplane mechanic, were ensnared by a federal probe led by U.S. Homeland Security Investigations, or HSI.

The Gulfstream GIII private jet they sought happened to be parked on a tarmac frequently used by multimillionaires at the Sanford Orlando International Airport ― where it was being watched by one of nation's few specialists targeting "narco planes" used for drug smuggling.

So, instead of netting quick cash, Pimentel and Dallas resident Tomas Borjas Mendez, 38, landed prison stints for forking over $600,000 to illegally buy a plane meant for smuggling cocaine. They paid for the plane after collecting cartel drug profits from large cities and small towns throughout the Midwest and Southeast, including Chicago, Atlanta and Nashville.

The case, which landed in federal court in Orlando, has some strange twists including a rattled Uber driver, a delayed kidney transplant, a plan to bribe a U.S. Customs official, a West Palm Beach takedown and a grisly threat.

The case illustrates how Mexican cartels exploit rarely policed secondary airports and private plane tarmacs throughout the U.S. It also shows how a dogged task force based out of the HSI's Tampa field office outsmarted them.

Details about the cartel's plan, provided during agents' interviews with Pimentel, reveal the complicated route and many stops the plane would have taken to haul 2,500 kilos of cocaine sourced from Colombia to Venezuela before the drugs were transferred into smaller shipments bound for Mexico and eventually the U.S.

Pimentel, a plane mechanic in Mexico, said the cartel was testing him and Borjas to see if they could successfully acquire a plane. The specific cartel, which Pimentel didn't name, planned to destroy the jet after one use to avoid detection by investigators, reasoning that drug dogs could sniff the cocaine residue if police ever stopped the plane on a subsequent trip.

Cartel leaders wanted to buy a new jet every month from the Orlando area. Before realizing they were on agents' radar, they preordered 10 planes.

They didn't plan on interference by Ryan Gorman, a veteran HSI special agent who has spent years honing a rare expertise detecting drug planes. His secret weapons included an Orlando plane broker, who worked as a criminal informant, and an undercover agent.

"We figure if we can stop one of these airplanes from ever being purchased, then we can stop a huge flow of drugs on that day," Gorman told The Courier Journal. "If we can disrupt their transportation, we can disrupt their whole game."

The Courier Journal reviewed court documents and transcripts and traveled to Florida to meet with Gorman, touring two private jet airports visited by the cartel associates in Sanford, a 30-minute drive north of downtown Orlando, and DeLand, a 30-minute drive southwest of Daytona Beach.

"It's really a nice niche Ryan's been able to carve out to target planes," said Assistant U.S. Attorney Shawn Napier, who prosecuted the case against Pimentel and Borjas.

Also, Gorman and his fellow agents found a way to seize planes from cartels and other criminals even without evidence to build a criminal case. They used asset forfeiture laws and sometimes convinced judges they had probable cause because the plane buyers falsified their identities, hiding the aircrafts' true owners. The planes' new owners could have fought to get the aircraft back, but typically no one shows up in court, where a judge would scrutinize their identity and what they were doing with the plane.

During the past decade, Gorman's team, including HSI task force officer Kyle Coffman, and investigators with other area federal agencies, have confiscated 77 planes ― including some capable of carrying 3.5 metric tons of cocaine.

"He's taking chess pieces off the board one piece at a time," Napier said.

Cartel "big people" hatch a plan

A request by a relative imploded Pimentel's modest family life in Mexico.

He claims his father left when he was age 3, leaving his mother to struggle to raise him and his four siblings. At the end of school days, Pimentel cared for cattle, learning early on the value of hard work. He put himself through trade school, becoming an aircraft mechanic years ago.

He and his wife were raising their daughter, age 6, and son, age 2, in a $30,000 home.

A relative from his father's side, higher up in a cartel, contacted Pimentel with a request after years of estrangement. Investigators aren't sure if Pimentel was motivated by family obligation or a fear to resist the cartel. Pimentel told the judge during his sentencing hearing he was afraid, knowing the brutality of cartels.

"There was someone who was leading me to do this," he told the Orlando judge. "They were threatening me directly."

He didn't elaborate on the threats or the cartel. Gorman told the judge he consulted with U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agents, who confirmed it was Pimentel's relative who was a cartel member, not Pimentel. Details about the location where Pimentel lived, worked and was approached by the cartel remain hidden in HSI files and sealed court records.

Cartel supervisors, or "big people," met with Pimentel at a table in a Mexican restaurant to discuss a multimillion-dollar plan involving several countries and several felonies.

He suspected others at the table were corrupt Mexican government officials on the cartel payroll. Pimentel, born with undersized kidneys, was very ill and waiting for a kidney transplant.

Still, when he was given orders, he didn't ask questions.

Instead, he headed to Dallas to meet with Borjas, a family man and an expert in repairing planes.

Borjas' attorney, Robert Zlatkin, said he couldn't discuss why Borjas got involved in the scheme.

"I have to be very, very careful because of confidentiality and the nature of the case," he said. "He’s an exceptionally nice guy. He was a very respected mechanic with the best of training, a self-made man."

Pimentel knew Borjas because years ago he asked Borjas to repair a plane in Dallas. In the U.S., Borjas had easier access to more airplane parts and a reputation as a go-to mechanic. This time, Pimentel offered to pay Borjas, who was more fluent in English, to tag along on the search for a Gulfstream and to inspect the aircraft for the cartel.

Agents and prosecutors say Borjas ended up getting more involved, traveling to other cities and states to gather stacks of cash from cartel drug sales. They also claim Borjas planned to buy many more on behalf of the cartel.

His attorney argued that Pimentel played the bigger role in dealing with the cartel.

"I think his role was a lot smaller than portrayed by the government," Zlatkin told The Courier Journal.

To pay for the first plane from Florida, Borjas tried to arrange for cartel associates to collect cash from drug sales in several states and drive them to the Orlando area. He grew irritated after realizing most were too scared of being pulled over by police because they were in the country illegally and didn't have valid U.S. driver's licenses.

Borjas headed out of town to pick up the money himself, an endeavor that took months. Borjas once complained about lack of sleep after a three-day drive to Nashville and Atlanta. He also discussed collecting drug money in Charlotte, North Carolina, and the orange-grove-dotted Clewiston, Florida, billed as "America's sweetest town" for its production of raw and refined cane sugar. For the cartel, it was a sweet spot for a stash house, used as a transshipment point to collect drug profits from the Miami area.

After his arrest, Borjas told investigators how he walked into the Clewiston house and found Hispanic women hurriedly counting and sorting mass amounts of cash in bundles.

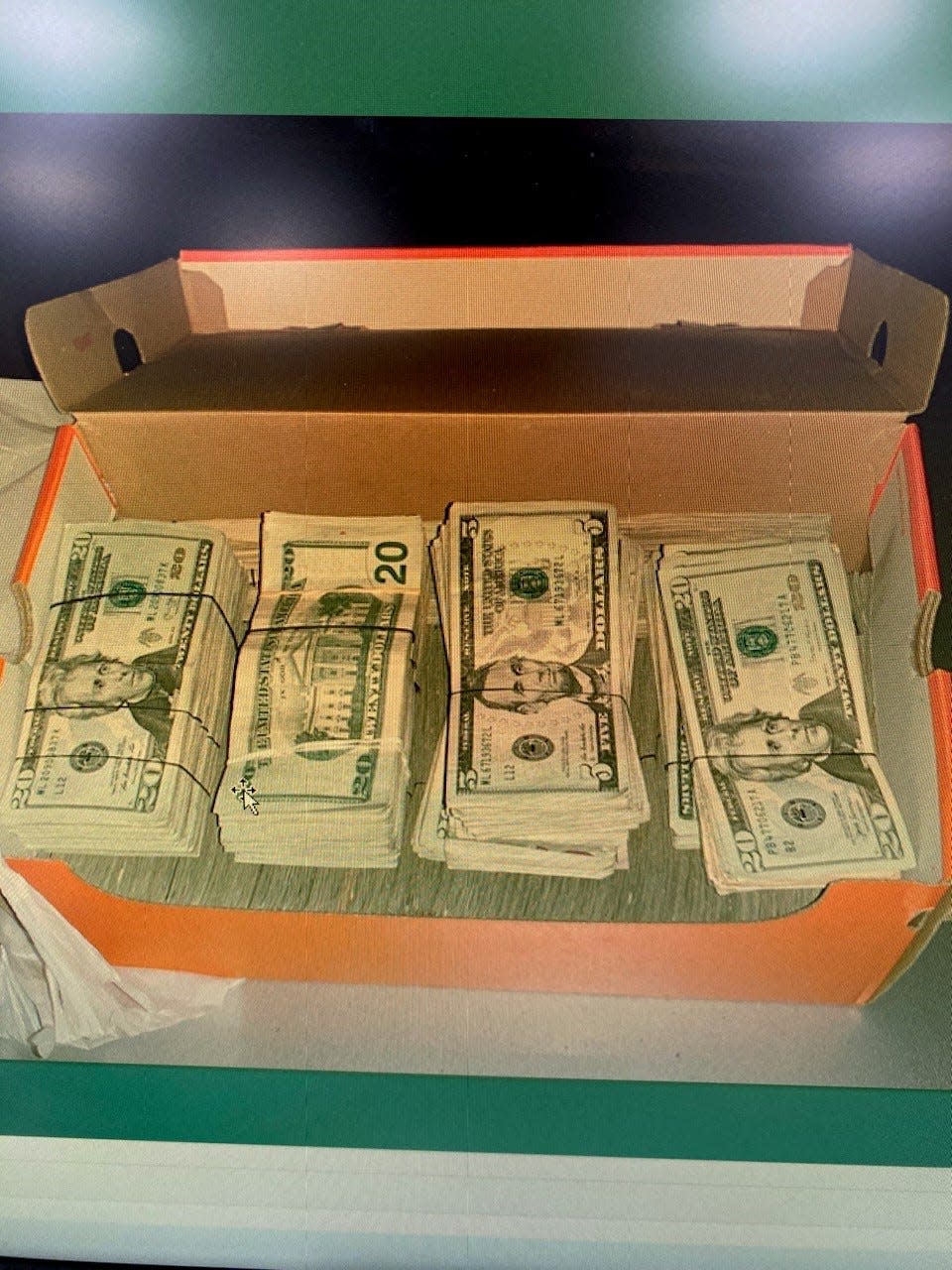

Borjas and Pimentel delivered one payment, totaling $80,000, to the Orlando-based plane broker in a Nike shoe box.

In June 2021, Borjas paid a driver to take him back to Florida, where he and Pimentel stuffed a brown duffle bag with $363,000 bundled in rubber bands into the trunk of the plane broker's car as final payment for the plane. Agents seized the plane, but waited to charge Borjas and Pimentel.

Gorman, the lead agent on the case, knew if he wanted to charge them, he would have had to convince a judge to sign off on an arrest warrant based on probable cause. For this, Gorman would have had to file an affidavit, or sworn statement, revealing the identity of his confidential source, the plane broker. He felt it would be safer to wait until prosecutors secured a grand jury indictment, giving them more time to prepare their star witness.

The plane broker received a text with the image of a skull superimposed on his wife's face, something he and agents viewed as a cartel threat, Gorman said.

When agents finally arrested Pimentel, he had flown from Mexico to West Palm Beach on a Gulfstream GIV. Agents moved it to arrest him after he got inside an Uber to head to breakfast with an associate. The Uber drive was stunned.

Pimentel stayed calm, but asked a lot of questions, paranoid that the agents were actually criminals in disguise trying to rip him off. The agents wore "HSI" marked bullet-resistant vests and flashed gold badges, but in Mexico, the larger cartels often wear police or military tactical gear.

Gorman and others took Pimentel to their office and show him their badges for closer inspection. Then, their suspect began to talk.

Pimentel previously told the plane broker that one of his relatives sold cocaine for the cartel in Canada, where he could fetch as much as $100,000 per kilo, compared to about $30,000 in Florida. He said it was difficult to get the drug profits back to Mexico, with a lag time from relying on ocean vessels. Another complication was that his relative was stuck in Central America, unable to fly to the U.S. to tend to cartel business because he feared he was a target of a DEA investigation.

In Florida, Pimentel met with a man he thought was a corrupt U.S. Customs Border Protection official ― an undercover agent ― in June 2021 and offered a recurring bribe of $10,000 a month to help get large amounts of cash on planes headed out of the Orlando area bound for Mexico. He said cartel couriers were concerned about driving around with lots of cash because they could get caught by state troopers.

After his arrest, Pimentel didn't reveal any information that would help agents determine if he was just boasting or if this Canadian drug ring really existed.

Agents arrested Pimentel in December 2021, a month before his scheduled kidney transplant in Mexico.

'Noisy and dangerous'

There's a reason Mexican cartels wanted older Gulfstreams when many American plane owners didn't.

"The Gulfstream model the traffickers really love are the GIIs and GIIIs," Gorman said "They have massive range, flying thousands of miles without having to get gas. They can haul a significant load and they're hardy.

"I once had a pilot tell me, if a Gulfstream will start, a Gulfstream will fly."

However, they don't always reach their destination. Some have not been properly maintained, others run out of gas or fail to land on crude dirt airstrips, crashing into mountains, jungles or the ocean. Some "narco pilots' who fly for the cartels don't make it out alive.

Steven Tochterman, a retired special agent with the Federal Aviation Administration, said he wouldn't fly in one.

"They're throw-away aircraft," he said, describing many as old and often in need of maintenance. "They're taking a risk."

Older Gulfstreams also are incredibly noisy, leading to their inclusion on a ban in the U.S. by the FAA unless they were modified. Aviation International News reports on the 2013 regulations noted that some "hush kits" to lessen noise cost between $800,000 to $1 million. Many plane owners didn't want to pay that much, Tochterman and Gorman said, flooding the market with planes for sale at a lower price.

More: Cartel-backed pot grows linked to human trafficking, inhumane working conditions

While the American plane owners saw it as a problem, cartel bosses in Mexico ― where there were no noise restrictions ― saw it as an opportunity.

Occasionally losing a pilot and a load to a crash is considered the cost of doing business by the wealthy cartels, especially the world's top two dominant super cartels, the Sinaloa Cartel, once headed by infamous drug lord "El Chapo," and the lesser known but equally powerful Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación, knowns as CJNG. National Drug Threat Assessment reports by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration list those two Mexican cartels as the top exporters of illegal drugs into the U.S., including cocaine and deadly fentanyl.

Mexican cartel members sent Pimentel on a mission to buy the 12-seat jet, which was supposed to be flown from the Sanford airport to Toluca, the capital of the state of México that's a 90-minute drive west of Mexico City. Here, the interior would have been gutted to remove the seats and make room for 2,500 kilograms of cocaine.

A "narco pilot" hired by the cartel would turn off the plane's transponder to fly off-radar to the jungle in Venezuela. Here, cartel members would load the cocaine, likely sourced from Colombia, onto the plane to head to a Central American transshipment point, a temporary destination. Then the drugs likely would be driven into Mexico to avoid the attention that comes with a private jet.

From Mexico, the drugs would be divided up into smaller shipments and loaded onto semi-trucks, some likely hidden amid avocados and other legitimate exports, bound for the U.S. and possibly Canada.

The cartel couldn't simply fly the plane full of drugs directly from Venezuela or Mexico to the U.S. because they feared detection by the military, U.S. Customs or other federal agents.

Suspicious flight patterns are flagged by HSI's Air and Marine Operations Center in Riverside, California, which helps detect and track boats and planes and provide intelligence to agents like Gorman.

In the case against Pimentel and Borjas, Gorman put together a strong case bolstered by secret recordings and surveillance footage, so both defendants pleaded guilty last year to conspiracy to trafficking cocaine internationally for their roles in buying a plane on behalf of a drug cartel.

Pimentel is serving a sentence of five years and six months in federal prison, where parole is not an option. Borjas is serving a sentence of four years and six months.

And Gorman is looking skyward for his next targets.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Mexican drug cartels seek private jets near Orlando to ship cocaine

money

money