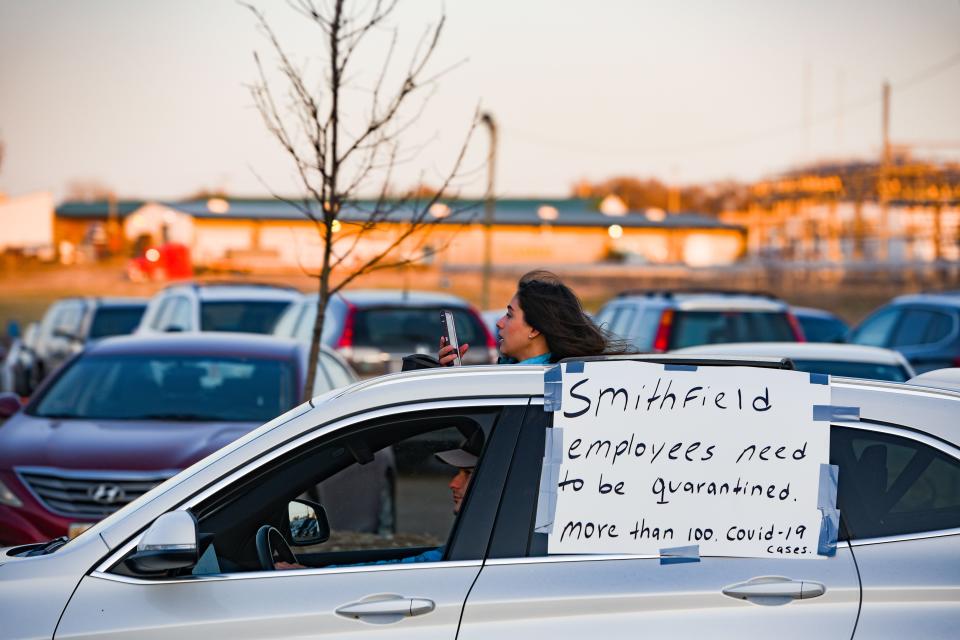

Unfounded shortage panic led to 'unsafe conditions' for meatpacking workers, report says

When federal health officials drafted their first recommendations in response to a COVID-19 outbreak at a meatpacking plant, Smithfield Foods CEO Ken Sullivan grabbed his pencil.

It was late April 2020, and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention staff had just toured Smithfield's Sioux Falls, South Dakota, pork processing plant, where 900 employees had contracted the virus. Two had died.

The staff created a list of recommendations. They wrote that the company should spread out dining hall tables, give employees face masks and designate paths where workers would only move one direction.

More: Family of Marshalltown meatpacking worker who died of COVID-19 sues JBS

Sullivan marked up the proposal, scribbling stars next to recommendations that the company couldn't implement in its aging plant. He scanned the document and emailed it to Department of Agriculture Undersecretary Greg Ibach, according to internal communications published in a U.S. House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis report released Thursday morning.

"The best we can do in these environments is aggressively mitigate risk, not eliminate it," Sullivan wrote.

"We are on it," Ibach responded an hour later.

The report, written by the staff of the 12-member, Democratic-controlled subcommittee, found that Sullivan's lobbying, with the administration's help, resulted in "watered-down" guidance from the CDC, setting the stage for weak regulations on all meatpacking plants in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The report argues that meatpacking CEOs — led by Sullivan — convinced President Donald Trump's agriculture department appointees that the country was heading for a food shortage if the plants didn't continue running as usual.

At the same time, according to emails obtained by the committee, industry data showed that the country had enough meat in storage to fulfill demand for more than a year. In one email, an industry lobbyist accused Sullivan — her group's client — of "stoking fear."

The subcommittee staff report also argues that local officials' attempts to regulate Tyson Foods' Waterloo factory in Iowa helped motivate an executive order from Trump, declaring that plants needed to stay in operation.

"Meatpacking companies knew the risk posed by the coronavirus to their workers and knew it wasn’t a risk that the country needed them to take," the authors of the report wrote. "They nonetheless lobbied aggressively — successfully enlisting USDA as a close collaborator in their efforts — to keep workers on the job in unsafe conditions."

In a statement after the report's release Thursday, Smithfield spokesperson Jim Monroe said the company's concerns about a food crisis "were very real." He added that the company spent $900 million on safety improvements, exceeded federal regulations and let workers stay home.

"Did we make every effort to share with government officials our perspectives on the pandemic and how it was impacting the food production system? Absolutely," Monroe said.

Tyson Foods spokesperson Gary Mickelson added in an email that his company's communications with federal agencies helped the company better handle the challenges of the pandemic.

"This collaboration is crucial to ensuring the essential work of the U.S. food supply chain and our continued efforts to keep team members safe," he said.

National American Meat Institute CEO Julie Anna Potts, in a statement, said the subcommittee report ignored some facts. She said companies spent billions of dollars to protect workers "while keeping food on Americans' tables."

The North American Meat Institute is the lobbying firm for industry giants, including Smithfield, Tyson and JBS.

“The House Select Committee has done the nation a disservice," Potts said. "The Committee could have tried to learn what the industry did to stop the spread of COVID among meat and poultry workers, reducing positive cases associated with the industry while cases were surging across the country. Instead, the Committee uses 20/20 hindsight and cherry picks data to support a narrative that is completely unrepresentative of the early days of an unprecedented national emergency.”

USDA analysis: Iowa meatpacking towns among nation's hardest hit

A spokesperson for Republican U.S. Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks, the only Iowan on the subcommittee, did not respond to a call or email seeking comment Thursday.

Meatpacking is a particularly important industry in Iowa, the nation's leading pork producer and among the top 10 states for cattle, lamb and turkey production. Tyson Foods and JBS have large factories dotted throughout the state. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 33,000 Iowans worked in the animal slaughtering and processing industry in 2020.

Plants like these became some of the biggest hotspots for the virus as the pandemic reached the United States two years ago, largely because they their workers stand shoulder to shoulder on lines where they cut and debone carcasses, according a September 2021 USDA Economic Research Service paper.

More: 'They'll watch Iowans get sick': Union chief criticizes Iowa proposal to ban vaccine mandates

In May 2020, Iowa counties with meatpacking plants had some of the highest infection rates of any U.S. rural counties.

The Food & Environmental Reporting Network, which independently tracked COVID-19 cases, estimated that 6,600 Iowa meatpacking employees contracted the virus and 22 died.

U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn, the chair of the subcommittee, said in a statement Thursday that federal officials could have decreased the number of illnesses and deaths had they enforced stricter rules on the plants.

"The shameful conduct of corporate executives pursuing profit at any cost during a crisis and government officials eager to do their bidding regardless of resulting harm to the public must never be repeated," said Clyburn, D-South Carolina.

Sonny Perdue convinced CDC director that regulations would create 'protein shortage'

In mid-April 2020, after objections from Smithfield's CEO, the CDC issued its recommendations for the Sioux Falls plant. The agency injected several qualifiers into the final edition, including a statement that the recommendations "are discretionary and not required," according to the subcommittee report.

Some career staffers at the CDC objected to the changes.

"It really muddies the guidance, when we start putting these waffle words into it," Henry Walke, who was the CDC's incident manager for COVID-19 response, told the subcommittee.

Robert Redfield, the CDC director at the time, told the subcommittee that meatpacking industry leaders convinced him that stricter recommendations would "shut (Smithfield's Sioux Falls) plant down." He added that then-U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue made a "very, very passionate presentation."

"I became convinced that the Secretary of Agriculture's concerns were right, that if this thing goes on too long, that we are going to have a protein shortage," Redfield told the subcommittee.

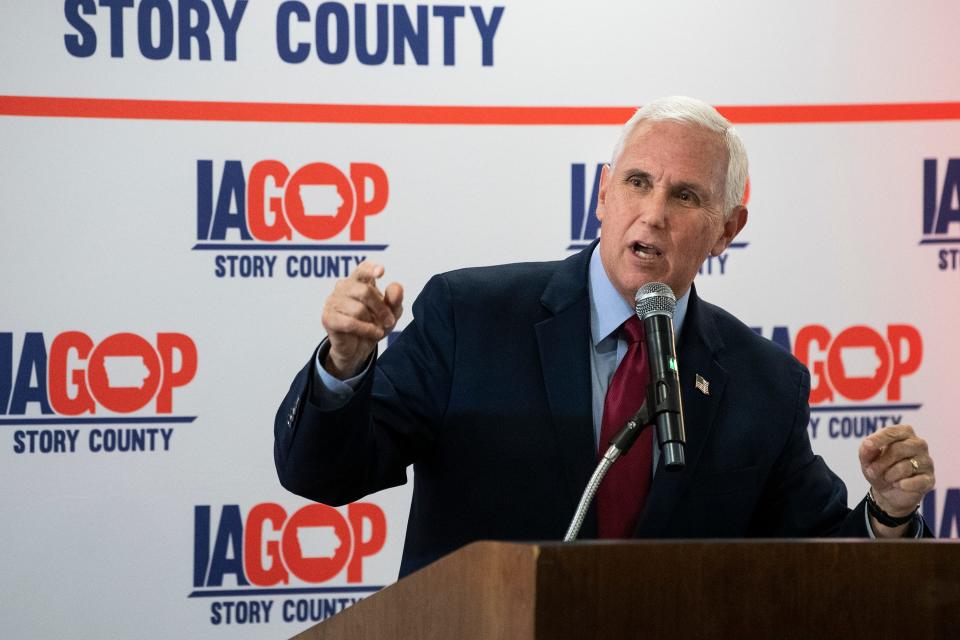

After call with meatpacking CEOs, Mike Pence urged employees to work

Before the Sioux Falls outbreak, meatpacking executives coordinated several calls with high-level White House officials, emails released by the subcommittee show.

Potts, the head of the North American Meat Institute, sent an email to CEOs of Tyson, Smithfield, JBS and other meatpackers on April 2, 2020, to discuss what points they wanted to make in a call with Perdue the next day.

"Our overriding message is how dire a situation we are in if we can't stem workforce absenteeism during the next few week," she wrote.

Potts added that they should tell Perdue they were keeping workers safe and were trying to "incentive" employees to continue showing up.

"We need the Administration's help in assuring those workers they are valued, protected by appropriate (protective equipment) and sanitation and should not be entitled to unemployment benefits if they are otherwise able to work through the pandemic," Potts wrote.

More: COVID infections among meatpacking workers much higher than previously reported, new report says

Sullivan, the Smithfield CEO, responded to the group that they didn't need to talk to Perdue about protective equipment.

'We're not asking for N-95 masks or anything like that," he said. "The ask is for the President, as well as all levels of government, to make more explicitly clear that food and agriculture workers are front line workers fighting the pandemic. The industry needs help, straight from the bully pulpit, to reinforce our patriotic duty to produce food for the country. All our plants are seeing cases. In the absence of positive messaging about their special role, workers are getting scared."

He added: "The meatpacking industry, and the entire agricultural complex along with it, are at risk of collapse. We're seeing it develop before our eyes. We need help with the message!!!"

Five days later, as the group prepped for a call with Perdue and Vice President Mike Pence, Potts urged the CEOs to ask for help convincing their employees to return to the plants. She said that slowing processing lines and shutting down plants was "potentially catastrophic."

"Fear among your workforce is the greatest enemy we have now," she wrote.

At a news conference after the call, Pence addressed food industry employees "at every level across the country."

"You are vital," the subcommittee report quoted him as saying. "You are giving a great service to the people of the United States of America. And we need you to continue, as a part of what we call our critical infrastructure, to show up and do your job."

Meat lobby spokesperson: Smithfield Foods is 'directing the panic'

The subcommittee report, however, said the country in fact did not show signs of a food shortage. It said that according to the agriculture department, the U.S. exported about 640 million pounds of pork in April 2020, 22% more than it did the same month a year earlier.

As of March 31, 2020, it had 622 million pounds of frozen pork in cold storage, according to the department. Institute for Agriculture & Trade Policy researcher Steve Suppan estimated that the supply was sufficient for 14 to 18 months, the subcommittee said.

Yet on April 12, 2020, when Smithfield announced it would temporarily close its Sioux Falls plant as COVID-19 cases climbed, Sullivan said in a statement that the country was "perilously close to the edge in terms of our meat supply," it found.

That same month, it said, Tyson took out an ad in the New York Times, Washington Post and Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, declaring that "the food supply chain is breaking."

Internally, despite the fact that they represent Smithfield and Tyson, employees at the National American Meat Institute were scratching their heads, according to emails the subcommittee released.

Sullivan "is intentionally scaring people," the firm's spokesperson, Sarah Little, wrote to another employee on April 15, 2020.

"Smithfield has whipped everyone into a frenzy and (North American Meat Institute CEO) Julie Anna has to clean up (their) mess," Little wrote the next day. "The industry and Ag interests are furious."

She added that Smithfield had earlier that month asked the lobbying firm to produce an advertisement encouraging workers to continue coming to work, something the group declined to do, according to the emails.

"They demanded national TV," she wrote. "Then when the (South Dakota) plant was closed, they freaked out about shortages. Then last night they wanted us to issue a statement that there was plenty of meat, enough that it was for them to export. You can NOT make it up."

"Oh. My. Goodness," responded Robin Troy, the lobbying firm's director of conference services and marketing. "Their comm team is a mess."

"It comes from Ken Sullivan the CEO," Little wrote. "He is directing the panic."

"Ugh," Troy responded. "You can't mess with people's bacon — all hell breaks loose."

In an email to the Des Moines Register on Thursday, Little wrote that U.S. grocery stores continued to have a supply of meat available to customers throughout the pandemic.

"However," she said, if plants had continued to shut down "at the pace and varying nature that was occurring in the early spring of 2020, the food supply would have faced greater challenges."

Subcommittee: attempts at oversight in Waterloo lead to Donald Trump's executive order

After executives' conversations with Perdue and Pence, Potts wrote that public attention on employee infections could lead to local regulations. She was particularly concerned about Waterloo, where local officials visited Tyson Foods' pork plant.

"Health departments are showing up unannounced at plants (Waterloo IA), and the media reporting is going to create more attention from health departments and governors in other communities (in my opinion)," Potts wrote on April 11, 2020, according to emails released by the subcommittee. "It seems to be cascading and our friends at USDA and the VP's office are not able to stop it."

In its report, the subcommittee contended that attempts at oversight like those in Waterloo motivated meatpacking executives to lobby for an executive order to override state or local regulations.

Sullivan, the Smithfield CEO, asked Tyson CEO Noel White in an April 11 email to discuss "COVID and a possible Executive Order from the President."

Two days later, according to another email, a Tyson attorney sent the North American Meat Institute a proposal for an executive order. According to the subcommittee, the lobbyists later said in emails that the order would override any local regulations on packing plants.

Trump signed the executive order "to keep meat and poultry processing facilities open" on April 28, 2020. According to the subcommittee report, the order did not have any direct sway because the agriculture department didn't write the required rules for implementing it.

The executive order also included language that lobbyists and meatpacking CEOs believed gave them exemption from COVID-19-related lawsuits, according to the subcommittee.

That night, after Trump signed the executive order, an American Farm Bureau Federation spokesperson, in an email the subcommittee cited, asked a North American Meat Institute spokesperson if the action protected companies from legal liability.

"It is subtle, but it does," Little, the meatpacking lobby's spokesperson responded. "We are avoiding mentioning that at all costs. It is a terrible fact, but it is what it is."

A federal judge in Iowa ultimately ruled in December 2020 that Trump's executive order did not shield Tyson from a lawsuit filed by the family of a Waterloo employee who died of COVID-19. Families of at least seven workers who died with the virus are suing the company in pending cases.

In one lawsuit, lawyers accused Tyson's Waterloo managers of betting on how many workers would contract the virus, leading to an internal investigation and the firing of seven employees.

Black Hawk County Sheriff Tony Thompson would later tell ProPublica that 1,500-1,800 of the factory's 2,800 workers contracted the virus in 2020.

In December 2020, Tyler Jett covers jobs and the economy for the Des Moines Register. Reach him at tjett@registermedia.com, 515-284-8215, or on Twitter at @LetsJett.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Meatpacking companies got Trump administration to limit COVID rules

money

money