A manhole cover launched into space with a nuclear test is the fastest human-made object. A scientist on Operation Plumbbob told us the unbelievable story.

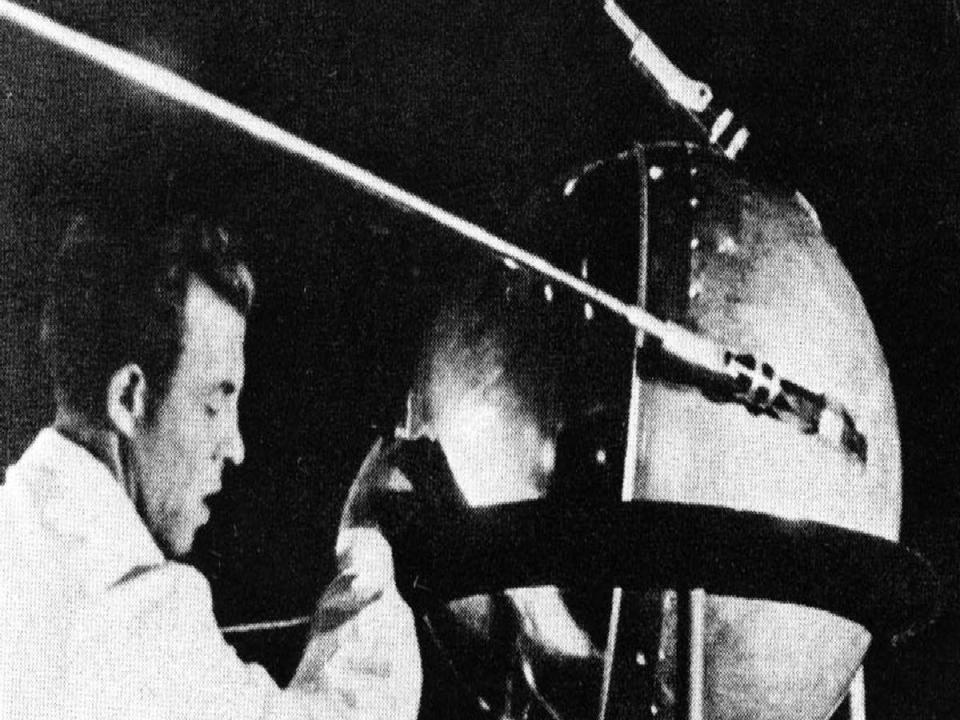

Robert Brownlee was on the Operation Plumbbob team that launched an object in space before Sputnik.

They put a manhole cover above a nuke underground, and the explosion shot the iron cap into space.

The fastest human-made object was part of the US government's nuclear testing in the 1950s.

When I first saw this story on an old Quora thread, I didn't believe it.

How could an iron manhole cover be the fastest human-made object ever launched?

I honestly pictured something akin to the exploding manhole covers that terrify NYC residents:

It wasn't like that. This manhole cover was shot into space with a nuclear bomb.

Robert Brownlee, an astrophysicist who designed the nuclear test in question, told Insider the unbelievable story in 2016, before he died at the age of 94 in 2018.

Brownlee refuted the non-believers and asserted that yes, it likely was the fastest object that humankind ever launched.

Here's how Brownlee says history was made.

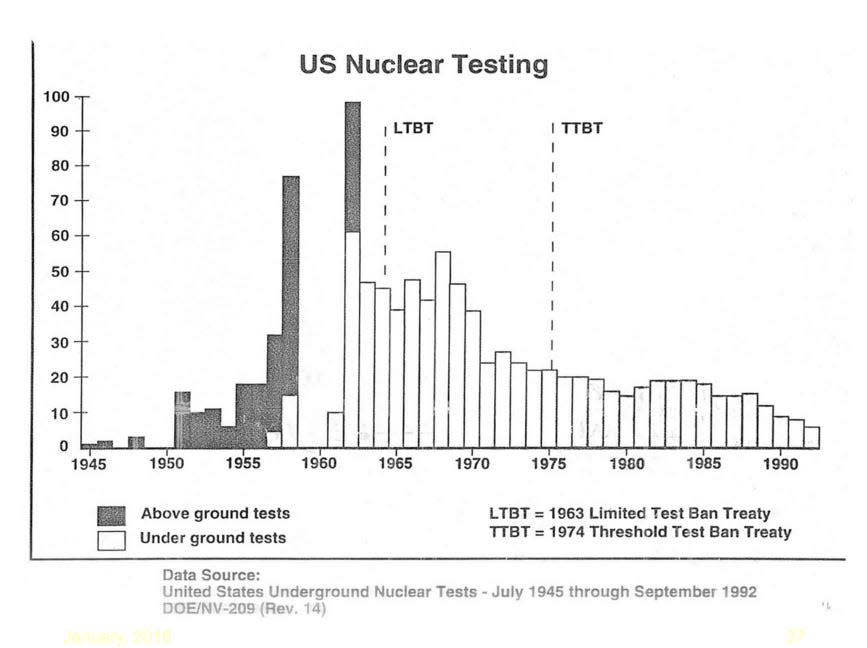

From 1945 until 1992, the US detonated 1,054 nuclear bombs in tests.

By the 1950s, the US government and the public were concerned with the radiation that nuclear bombs could release into the atmosphere.

By 1962, the US was conducting every nuclear test underground.

But the very first underground nuclear tests were a bit of an experiment — nobody knew exactly what might happen.

The first one, nicknamed "Uncle," exploded beneath the Nevada Test Site on November 29, 1951.

Uncle was a code for "underground."

It was only buried 17 feet, but the top of the bomb's mushroom cloud exploded 11,500 feet into the sky.

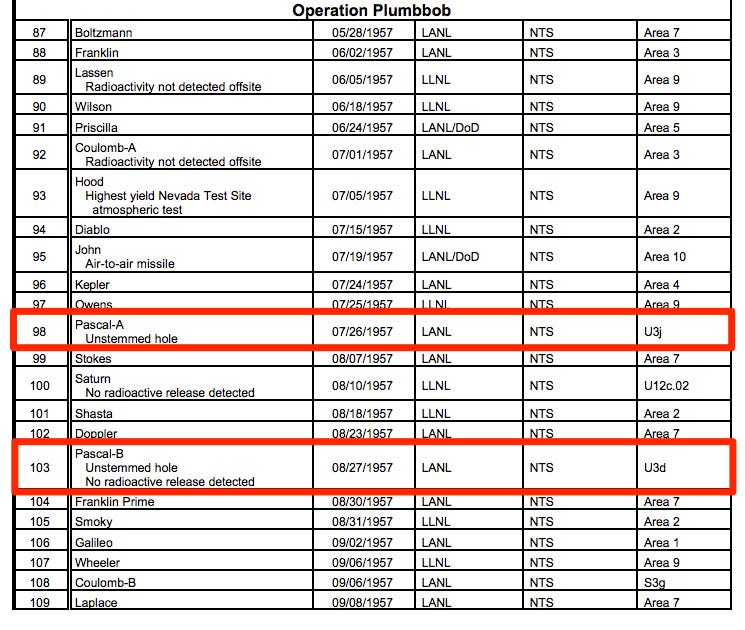

The underground nuclear tests we're interested in were nicknamed "Pascal," during Operation Plumbbob in 1957.

Brownlee said he designed the Pascal-A test as the first that aimed to contain nuclear fallout. The bomb was placed at the bottom of a hollow column — 3 feet wide and 485 feet deep — with a 4-inch-thick iron cap on top.

The test was conducted on the night of July 26, 1957, so the explosion coming out of the column looked like a Roman candle.

Brownlee said the iron cap in Pascal-A exploded off the top of the tube "like a bat much hotter than hell."

Brownlee wanted to measure how fast the iron cap flew off the column, so he designed a second experiment, Pascal-B, and got an incredible calculation.

Brownlee replicated the first experiment, but the column in Pascal-B was deeper at 500 feet. They also recorded the experiment with a camera that shot one frame per millisecond.

On August 27, 1957, the "manhole cover" cap flew off the column with the force of the nuclear explosion. The iron cover was only partially visible in one frame, Brownlee said.

When he used this information to find out how fast the cap was going, Brownlee calculated it was traveling at five times the escape velocity of the Earth — or about 125,000 miles per hour.

"The pressure at the top of that pipe was enormous," he told Insider in 2016. "The first thing that you get is a flash of light coming from the device at the bottom of the empty pipe, and that flash is tremendously hot. That flash that comes is more than 1 million times brighter than the sun. So for it to blow off was, if I may say so, inevitable."

Pascal-B's estimated iron cover speed dwarfs the 36,373 mph that the New Horizons spacecraft — which many have called the fastest object launched by humankind — eventually reached while traveling toward Pluto.

Brownlee said he expected the manhole cover to fall back to Earth, but they never found it. He concluded it was going too fast to burn up before reaching outer space.

"After I was in the business and did my own missile launches," he told Insider in 2016, "I realized that that piece of iron didn't have time to burn all the way up [in the atmosphere]."

Mere months after the Pascal tests, October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world's first artificial satellite. While the USSR was the first to launch a satellite, Brownlee was probably the first to launch an object into space.

Since it was going so fast, Brownlee said he thinks the cap likely didn't get caught in the Earth's orbit as a satellite like Sputnik and instead shot off into outer space.

Some people have doubted the incredible manhole cover story over the years. But Brownlee, with first-hand knowledge of the test, said he knows the truth.

"From my point," he told Insider in 2016, "it sure happened."

So the next time you look up at the stars, remember Brownlee's story. Somewhere out there, a manhole cover launched by a nuclear bomb is probably speeding away from Earth at about 125,000 mph.

This story has been updated.

Read the original article on Business Insider

money

money