Local history: The night the Akron Art Institute burned

Gone. It was all gone.

Nearly everything the Akron arts community had worked so hard to achieve over a 20-year span had disappeared overnight.

A terrible fire gutted the Akron Art Institute on Jan. 2, 1942, wiping out most of its collection, destroying priceless relics and leaving the museum without a permanent home for nearly a decade.

Long after the smoke cleared, the spark of creativity still flickered.

More: The future is now: 100-year-old predictions about 2022

The institute traced its humble beginnings to Feb. 1, 1922, when it opened in two basement rooms of the Akron Public Library at 69 E. Market St. It remained in crowded quarters for a decade until a library expansion forced officials to move the galleries in 1932 to the sixth floor of the M. O’Neil Co.

In 1936, the museum relocated to a rented space at 36 S. Howard St. in the improbably named Wiener Arcade. Workers packed up the institute’s growing collection of artwork with each move.

Mansion on Fir Hill

Weary of the vagabond life, Akron’s art patrons yearned for a permanent location. An anonymous donor gave $7,500 (nearly $139,000 today) toward the purchase of a building. Institute trustees selected the former home of Dr. Jedediah Commins at 135 Fir Hill near the University of Akron. Commins, a pharmacist who founded Glendale Cemetery, built the three-story mansion in 1840.

In 1937, the institute bought the residence from Commins’ descendants for $15,000 and spent another $10,000 on remodeling. The regal home had a grand ballroom, crystal chandeliers, stone fireplaces, walnut woodwork and an ornate staircase.

Architect John F. Suppes drew up plans for two large galleries on the ground floor and smaller galleries on the second level. The third-floor ballroom would hold classrooms and storerooms.

“Not only will we be getting a fine new art institute but we will be preserving one of the city’s most historic homes,” explained patron C.W. Seiberling, co-founder of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. “It is one of the few pre-Civil War structures still standing in Akron and is of such substantial structure it will stand for many, many years.”

University of Akron President Hezzleton E. Simmons was equally enthusiastic about the Fir Hill location.

“The creating of such a center which will permanently house the valuable collections of art owned by various individuals in the city who are seeking a safe place for their treasures will be a valuable asset to the art department of the university,” Simmons noted.

Nearly 2,000 guests attended the formal opening Nov. 22, 1937. Among the VIPs were Gertrude Seiberling, Edwin Shaw, Blanche Hower, Victor Schreckengost, Jane Barnhardt, George W. Crouse, Helen Gault, George Oenslager and Fred Butler III.

The first exhibit featured paintings, ceramics and other treasures owned by Akron residents. Guarding one gallery was a Japanese warlord’s silver and bronze suit of armor that James D. Tew, former president of the B.F. Goodrich Co., had lent to the institute. Also on view was financier William H. Hunt’s collection of 50 canes, including one that had belonged to Napoleon Bonaparte.

The surging crowd broke through the receiving line.

“Officers and trustees with their wives and husbands who stood there to greet arriving guests found themselves the center of many separate groups as friends and acquaintances stopped to praise and comment on the work done in a short time so that the city might have a permanent home for its art institute,” the Beacon Journal reported.

The Fir Hill museum served the community for four years. Its galleries filled with exhibits and its classrooms teemed with students.

In August 1941, officers celebrated their final payment of $7,500 on the building. Four months later, the United States entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Uncertainty gripped the nation as a new year arrived.

Fire at the institute

Akron Art Institute caretaker Alden A. McFarren, 70, and his wife, Mary, 68, were home about 8 p.m. Jan. 2, 1942, in their second-floor quarters when she heard a crackling noise downstairs. A wisp of smoke slithered into their room.

The horrified couple discovered that the ground floor was on fire. They raced to safety down the staircase just as flames engulfed the exit.

The fire had spread to the top floor by the time that firefighters arrived. Intense heat shattered the windows while 20 mph winds whipped the flames into an inferno.

Four engine companies and two truck units battled the blaze well past midnight. By dawn, the building was a charred husk.

A shudder ran through the arts community as institute officials converged on the scene to take an inventory. Most of the precious artwork had been destroyed.

The Charles and Lucy Baird Memorial Collection, a treasure trove of more than 300 Asian artifacts including one of the world’s largest acquisitions of ninth century Siamese porcelain, was the most significant loss.

Akron native Betsy Baird Neville, the wife of Edwin L. Neville, U.S. minister to Siam (now Thailand) and former U.S. envoy to Japan, donated the collection in 1939 to the University of Akron in honor of her parents. The school lent it to the art institute as a permanent display.

The donation included dozens of Chinese vases and other ancient relics from the Han, Sung and Ming dynasties; over 30 glazed pieces of Siamese Sawankhalok pottery from 800 to 900 A.D., and nearly 40 century-old prints from Japanese masters Utagawa Hiroshige, Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamaro.

Salvagers found 20 pieces in the rubble, but only a few were intact. Officials estimated the loss at $150,000 (or $2.7 million today). Insurance covered less than half.

Also destroyed in the fire:

• An inlaid table that had belonged to John R. Buchtel, benefactor and namesake of Buchtel College, forerunner of the University of Akron.

• An exhibit of watercolors by Fred Brucker from the Akron Society of Artists.

• A collection of portraits exhibited by the Women’s Art League.

• A display of 75 national prize-winning photographs.

A $4,000 exhibit of new acquisitions had escaped major damage after institute officials decided to leave it in a wall casement instead of putting it on display. Also spared was a $3,500 exhibit of 47 watercolors that had been removed two days earlier.

Total loss was estimated at $160,000 (nearly $3 million today).

Suspicion of arson

Akron Fire Chief Clarence E. Harris initially suspected faulty wiring as the cause of the blaze, but the case took a twist.

Deputy State Fire Marshal James Galehouse noted that the south gallery walls were destroyed while the floor was undamaged. The flames had spread unusually fast.

“It is extremely possible that the fire was fed by an inflammable liquid thrown on the walls,” Galehouse noted.

Police followed leads that teens had been seen near the institute before the fire. Galehouse indicated “definite circumstantial evidence of incendiarism,” but the investigation was inconclusive. No one was charged.

Institute officials promised the museum would return. They cleaned up a back room of the building and held classes.

Almost immediately, the permanent collection began to replenish. Hermine Z. Hansen, sister-in-law of oatmeal king Ferdinand Schumacher, died Jan. 8 at age 83 and bequeathed a Moorish art cabinet, a collection of brasses and several European paintings to the museum.

Institute director Edgar B. Foltz proposed converting the old library at East Market and High streets into galleries after the library moved in 1942 to the former Beacon Journal building at Market and Summit streets, the present-day Summit Artspace.

“There is a great need for an improvement of this kind,” Foltz said. “When people come here now, we haven’t a thing to show them but factories. We can have an art museum of which we could be proud.”

The war effort delayed plans. The art institute returned to its vagabond ways, sponsoring exhibits at Polsky’s, O’Neil’s and other places before setting up shop in 1944 on the third floor of the library.

Return to prominence

Following $260,000 in remodeling, the institute finally moved back to its original home at 69 E. Market St. in 1950. More than 3,000 people swarmed the five galleries.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” guests exclaimed.

The fire-damaged Fir Hill building was razed. The Chapel broke ground at the site in 1953 for its new church.

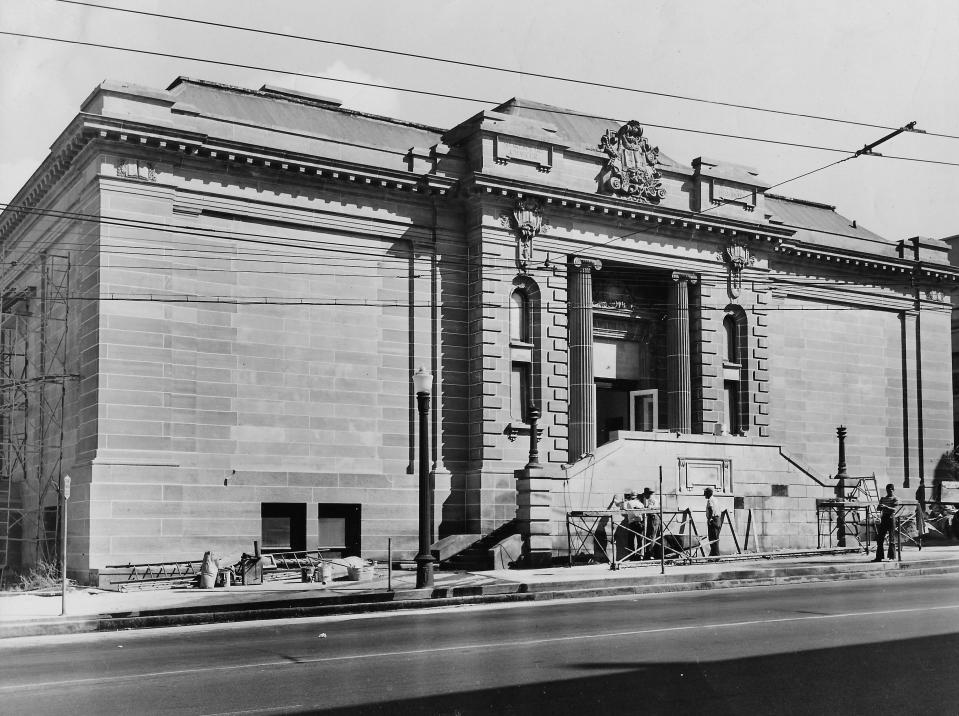

The institute stayed put for 30 years. Renamed the Akron Art Museum, it moved across East Market Street in 1981 to the former post office after a capital campaign raised more than $5 million to renovate the 1899 building.

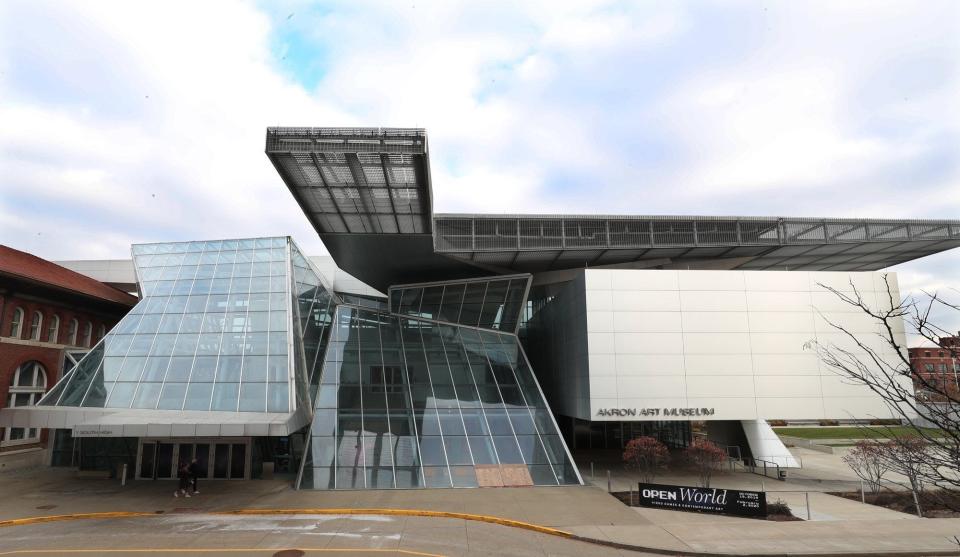

In 2007, the museum dedicated the 63,000-square-foot John S. and James L. Knight Building, an elevated structure of steel and glass. It raised $35 million for the addition and another $9.3 million for its endowment.

Akron Art Museum will observe its 100th anniversary in February, a celebration that will continue for two years.

Today, there are about 7,000 pieces in the permanent collection.

All was lost 80 years ago until the art institute rose from the ashes.

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com.

More: Trash turned treasure: Akron artist hunts for odd artifacts in Little Cuyahoga

More: Local history: Clarkins was king in Akron area before Kmart and Walmart

More: Staff profile: Meet the Beacon Journal’s Mark J. Price

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Local history: Fire destroyed Akron Art Institute in 1942

money

money