Lisa Taddeo Went All in on Depravity and Hollywood Came Knocking

“I signed up to be a writer, you know? Like a mole in a hole—I like being in total darkness—and now I’m doing this TV show stuff and it’s lots of meetings, lots of not-writing. You know? We already wrote the scripts. Don’t get me wrong, I’m totally grateful, I’m totally excited about all of the opportunities, it’s just—personality-wise—I’d rather be in a hole.”

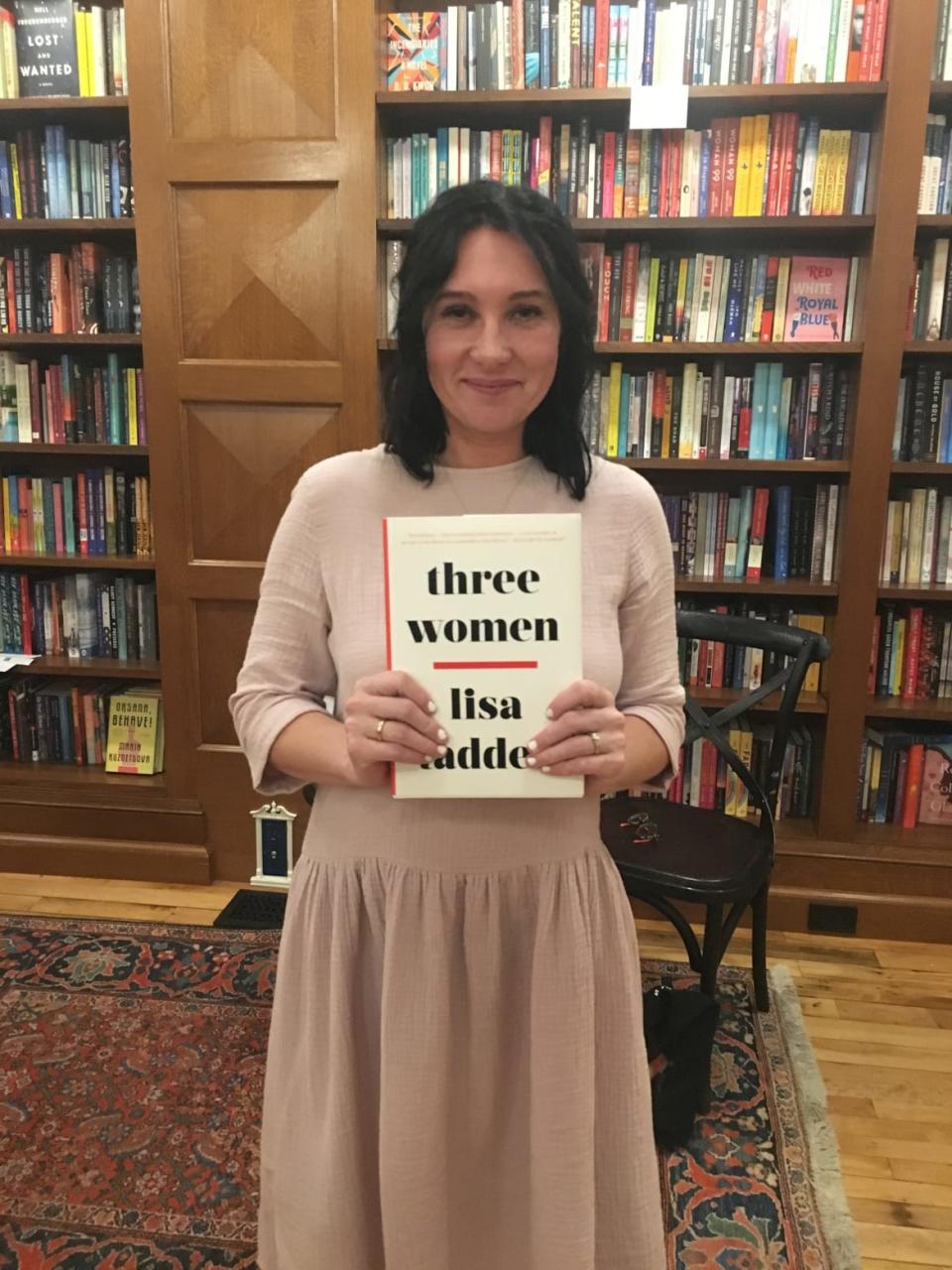

Lisa Taddeo laughs often as she speaks, gesticulating and brushing her thick, raven-colored hair from her face which is framed via Zoom against a backdrop so white and sterile that it has the look of a rubber-room in a mental asylum. I assume this is her office. Unlike her writing—concise, declarative—her spoken words tumble out in gushing run-on sentences.

“It’s hard for me because I have crippling, major anxiety. I like talking to people, I’m not agoraphobic exactly, but I am a little bit to the extent that knowing I have to be somewhere paralyzes me for the day. Now my entire day is scheduled, so I've been sort of reverse engineering my panic attacks where I'm like trying to schedule them, you know, in between, so it's been really, I mean, it's been great in the sense that I have a team of really great people working with me. It's mostly all women.”

She’s talking about her imminent jump from the page to the screen. Her last book—the nonfiction Three Women—garnered major acclaim for its intimate look at female desire and the depth of her reporting (Taddeo spent nearly a decade shadowing her subjects all over the country), and it was recently picked up for a series on Showtime. Now her follow-up—a beautifully brutal work of fiction called Animal—was just optioned for a film that will be produced by MGM and Plan B.

Animal has all the makings of a modern thriller flick. A femme fatale protagonist who some will champion and others will revile. Sex and violence. Surprise twists. Relentless critique of patriarchy.

The aforementioned protagonist is Joan, a woman who—following a series of traumas inflicted by men—lives in a somewhat perpetual crisis mode. We meet Joan just as she’s moved from New York to Los Angeles, where we join her as she mulls over a lifetime of hurt and horror and attempts to connect with a mysterious, beautiful woman called Alice. Things spiral from there.

Inside the front flap of the hardcover edition, you’ll find a phrase that could be considered something of a motto for Joan: I am depraved. I hope you like me. It isn’t difficult to see why some would think her depraved. She vacillates between being thrilled by the potential for debauchery and disgusted by her own willingness—or sometimes even eagerness—to wallow in it. Some readers will empathize with Joan’s actions while others will condemn them. But part of what makes her so compelling is that almost all will recognize some part of themselves in her. We tend to either admire or decry those who are brave enough—or exhausted enough—to say what we’re all thinking.

“I think very few people are actually depraved,” says Taddeo. “I think people who present depravity are most often just more honest. We all have crazy thoughts and crazy ideas and angers and jealousies, but we’ve been muzzled by our society. I mean, especially in America, you know, we've been living in this puritanical society that hasn't really—sure it's changed and things are changing—but at the end of the day it's always do as I say not as I do. I think if we were all more honest, we would all sound a little bit more crazy.”

Part of what made Joan a bit more crazy was the gruesome death of her parents, a plot point informed by Taddeo’s real-life losses: first the loss of her father to a car accident, then her mother to cancer. Much has been said by reviewers about Joan’s rage, but—while that rage is certainly present—as someone who has also lost a parent, Joan’s behavior didn’t read like anger to me: it seemed more like grieving.

I put the question to the author, “Do you think Joan is experiencing rage or grief?”

“For me, grief. You can go a lot of ways with it, you know, and I think one of the easiest ways is rage. Oh yes, Joan is grieving. In essence she’s been grieving since she was a little girl. It makes someone act really angry.

“You are one of probably like six or seven people who have brought it up. I tend to bring it up on my own, but I find that when people like you read it like that, it's like we can get into the conversation much easier. The hard part about explaining to people what grief is is that most people have not lost someone valuable. It's difficult to understand.

“I talk to my husband about it all the time. I'm totally traumatized by my history and my losses, and he has not really lost anyone who has had too much significance, and so when we talk about it, it's a surreal sort of dividing line between the way that we exist in the world and think about things. And I think that for people who haven't, it's hard, and you read Animal and you don’t know, you know, even though the grief is all in there, and it's quite obvious—it’s not like it's hidden, it's very much a big part of everything—but you can easily skate over it, and you can kind of hang onto the rage and the depravity just because it feels like stuff everyone has seen before.”

Goop Chief Content Officer Elise Loehnen and Lisa Taddeo speak onstage at Rolling Greens Nursery on May 18, 2019.

I know what she means, and if you’ve ever lost someone close, you probably do too. Grief is like swimming—you only really get it once you’ve been in the water.

“You know I did lose both my parents but not in the way that Joan did,” Taddeo continues, “but a lot of Joan's portrayal of loss is like the way that it felt for me. Like I was getting mauled to death by a tiger. But no one saw that on the outside, you know, ’cause I wasn’t… I've always been a pleaser, and I've always wanted people to feel like if they hugged me, that would make me feel a little better, you know? When in fact, nothing made me feel better at all. Being around people was not a balm, but I let people think that it was because it was, you know, societally approved to be around and to get back into the swing of things. That's something people always push when they're on the other side of it.

“I'll never forget one of my best friends—who I adore but who had not lost anyone at that time yet—several weeks after my mom died was trying to get me to go to her family reunion. And I was like, That is the last place in the world that I want to be right now. Watching happy mommies and daughters hug each other. I thought, I would want to sink into a hole.

“So for me Animal was definitely an exercise in describing how bad grief feels. And ditto for the miscarriage. I mean I've had a miscarriage, um, you know, and again, I didn't, you know, do what Joan does in the in the book, but it actually felt like that to me, you know? And that's the thing—how do you describe how something feels? You can use fiction to do that, and yet people are like, Oh, that's crazy. But it's not crazy! It’s how it feels. These things have happened to people. One of the things that I'm always so cognizant of is people do not… I say it in the book and Joan says it very pointedly—that people don't want to hear about a certain amount of pain. And they almost are angry at the person who's in pain for being in pain and we do the same thing when people are… when my mother was sick with cancer, I was enraged at her for dying, and for taking a long time to die or for dying at all, you know? All of those feelings are so brutal, and we often blame the person who's in pain because they're kind of taking us away from the illusion of what normal life is.”

There is a revelatory element that is key to Taddeo’s work. With Three Women, she was hailed—and in some cases disparaged—for exposing the typically hidden, often socially unacceptable aspects of female desire. Now with Animal, she is doing it again with grief, female rage, and misogyny. The outpour of praise from readers and reviewers alike indicates that these revelations have struck a chord.

At this point in our conversation, I tell her about how while in college my girlfriend and I had gone through a pregnancy and abortion, and how even though we were both pro-choice and had no moral opposition to the matter, we still felt a strange pressure to keep it a secret. It wasn’t until we later began discussing it with friends that we discovered seemingly all the couples had gone through the same thing. We’d all been carrying the secret, and it relieved a huge burden to share it around. To put it down.

“Totally,” Taddeo nods emphatically. “And you know with miscarriages one-hundred percent, that's what I've heard from so many people. We are the reason something feels so awful. Like you said, when you were going through that, it was like this big secret that makes it so much worse, you know? It just makes it so much worse. We’re so worried about what people are gonna think about us, right, and in the end it really doesn't matter because people are going to, you know, think whatever they want. They're going to find something else to nag you about, you know?

“One of my goals with Animal—one of my goals with writing in general, and anything I ever do, that I put out into the world—is to tell people to find the people who have been through a lot of grief or pain, loss, you know, whatever. To say to them, Look, I've been there or I've met many people who have been there. You know sometimes it just feels really great to hear someone describe something you've been through and to know that there's another side to it. It feels terrible to feel lonely. We just don't know the people who have been there.”

If the recipe for Taddeo’s writing includes one part revelation, then it’s also got two parts transgression. She dives deep into depravity, which is where much of the revelatory nature of her work resides: a willingness to illuminate the profane, agitating, sometimes outright horrible bits of life that we normally consign to the shadows. There terrible things people do to each other. There is a flavor to it that brings to mind the transgressive writers of the ’90s like Chuck Palahniuk or Brett Easton Ellis. I tell her that while preparing for the interview I found that there was only a single woman’s name mentioned on the “transgressive fiction” Wikipedia page amidst dozens of men.

“Why,” I wonder, “do women writing transgressive fiction get so little recognition?”

Taddeo scoffs. “We want our women writers to write narrators who have pluck and wit and are a little bit self-effacing and a little self-aggrandizing and, you know, have all these little knocks but are not really crazy—you gotta want to be friends with them, you know. You've got to want to invite them over and hang out with them. It's just such a load of bullshit. It really makes me angry, and I will tell you that I do not think that men are the culprits. I think that it's other women. I don’t know exactly what the statistics are, but there are more female readers than male readers in general, or book buyers rather. And when I talk to men, male readers that like, you know, go to readings and whatever—back when we used to do that stuff—they don’t say anything like, Oh, you can’t do that, you're a woman. Women do. I think it’s a method of keeping the lid on, keeping the secrets, an oh no don't tell our secrets kind of a thing. And not even like don't tell our secrets because we're all openly sharing them within our gender—don't tell our secrets because I don't want anyone to know me.

“I find genuinely that working with men, for me, has been easier than working with women in terms of doing things that are transgressive. I'm always more held back by females. Men do not do that. They're like, yeah that's cool.

“I remember what my editor at Esquire said to me—and it’s advice that I've, you know, taken throughout all of my writing—he said, don’t hold back. I will pull you back editing-wise. Just go completely crazy. Just be yourself.

“That’s something I say to my daughter too when she does stuff. I’m like, don’t inhibit your brain going into something. We can pull it back if we need to.

“One of my female friends—a very celebrated author, like wildly; she's just like stratospherically successful—told me that the one of her books that did not do that well was the one in which the mother was—not a bad mother—but not perfect.

“If you look at Elena Ferrante’s The Last Daughter—which I think is one of the most beautiful books—the mother leaves her two kids for like two years when they're young, and it's like… I have a daughter, and that idea is terrifying to me, but it's not horrifying to me to read the book. I’m not going to sit there and go this book is evil. That to me is basically book burning of a different kind—book burning without the fire. And I think that it is such unequivocal bullshit that we do that to each other as women.”

We continue talking about censorship, and I bring up that I’d just spent the night at Henry Miller’s house in Big Sur.

“I don’t think he could have existed today,” I muse. “The liberals who were supporting him back then would be calling to censor him today. Today he’d be censored by the liberals and the conservatives.”

Taddeo—who actually name-checked Miller in Animal, putting his name into the mouths of one of her most despicable characters—nods, saying, “I find this idea of purity—especially artistic purity—to be such a strange concept. I was cognizant of it while writing Animal, the idea that you really need to—especially as a female writer—exist in a finely calibrated world where you make sure that you're not upsetting anyone, make sure your characters are not upsetting anyone.

“I've always liked the transgressive. For example, Barry Hannah—who's one of my favorite writers—reading some of his stuff, it is misogynistic. It’s also not, sometimes. I think he talks about women and writes as female characters that even though it's obviously a man who wrote it, it still feels so true and real. I think that we get into this place where we just, you know, we're so gendered or so partisan… We live in the time now when you’re not allowed… when you must choose a side, you must be this extreme or this extreme, you cannot be in the middle, about anything. Otherwise, these people will disavow you while these people will destroy you. And I find that to be absolutely moronic.”

Taddeo’s work tends to straddle lines with unusual comfort. It is raw and transgressive yet poetic and vulnerable. It somehow manages to lay blame without pointing fingers—her characters know that terrible things have been done to them, and they also recognize when they are complicit in their circumstance. And she seems equally at ease in both fiction and nonfiction.

“Oh, fiction’s been what I've done my whole life,” she explains. “My first story for Esquire was a short story, then they started asking me to do nonfiction and I was like, Oh, so you get paid more for nonfiction. Whenever I'm reading about Shirley Jackson making a living on her short stories, I'm like, Oh, yeah, that was what was going on back then—it's not what's going on now. For me it was two things. For one a financial thing. I was like, Oh, so I can make money by writing? Okay, I kind of didn't know that. But I had always intended to write fiction… My next book is a collection of stories coming out next summer. But following that, I just signed a contract for kind of reported memoir about grief. I still like writing nonfiction, I just like writing both, so I will probably always do both.

“Whenever I talk to younger people, I never want to discourage them from short fiction. Honestly if it were up to me, probably my ideal thing to do would be writing short stories. That's probably all I really want to do. It just feels so contained. But it's a shame. It's really not something that is, you know, it's not it's like my agent and editor are like, Great! We're gonna release her collection! That's fine. I mean, you know, it's fine. I get it. I get what the marketplace is. I'm just sad about it.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

money

money