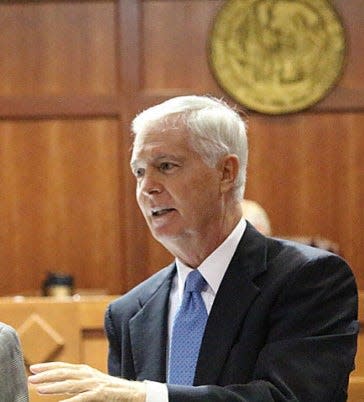

'My legacy is I don't want one': Former governor Mike Easley finds Southport as safe spot

On a foggy Wednesday morning in Southport, Mike Easley stands by his kitchen table — a piece of furniture he carved himself from the wood of a sunken ship — and gazes out the window toward the Cape Fear River.

His face lights up as a behemoth cargo ship slides out of a thick blanket of fog, heading to the Port in Wilmington. He crosses the room in two giant steps to reach the switch that operates his back porch light and flips it several times. He often does this to see if the river pilots will sound the ship’s horn.

On this day, no horn blows. He returns to the table and has a seat, still looking out toward the river. A few minutes pass and then the horn sounds. Easley stops to listen.

“Just one,” he said. “He’s just letting everybody know he’s around. If it’s five, then you know somebody’s getting ready to get hit.”

Easley’s knowledge of Southport and comfort on the water give the impression of someone who grew up on the coast. But like many who have since discovered the area, he got here as quick as he could.

When he arrived in Brunswick County in 1976, it was very different than it is today. Back then, there weren’t million-dollar homes on the beach strand. There was no booming tourist industry bringing in millions of dollars for the economy.

But what the area lacked in money, it more than made up for in community. Southport was the type of place where a 26-year-old farm boy from Nash County could learn about friendships, law and life.

More:What's really getting done in Southport? Here's a list of stalled projects.

Those lessons helped Easley grow into a leader, first as a prosecutor, then as North Carolina’s attorney general, and finally North Carolina’s governor.

Southport has also served as his safe spot through the ups and downs that have come with the state's highest political jobs.

A sense of community

The road to Southport started on a tobacco farm near Rocky Mount where he was one of seven children. At that time in his life, the words “party line” meant one telephone line shared between several families.

He described life on the farm as sometimes isolated.

“Your friends were whoever lived on the farm,” he said.

A conversation with his law school classmate Bubba Greer led him to Brunswick County, a place that was, at that time, as rural as his hometown. Bubba’s father, Lee Greer, was the district attorney for Columbus, Brunswick and Bladen counties. Greer offered Easley the position as assistant district attorney, a job he eagerly accepted.

“I ended up getting thrown right into superior court and trying jury cases right away,” Easley explained. “It was a baptism by fire.”

When Easley first moved to the area, he lived in a house on Oak Island that didn’t have heat or air and was in a state of disrepair.

“It was torn all to pieces,” Easley explained. “The sheetrock was torn out of it, and they said I could stay there for free if I’d fix it up.”

It took about a year, but he was able to make the repairs. Soon after, he moved to a home on Frink Drive in Southport and quickly became part of the community.

“There wasn’t any class structure here,” Easley recalled. “It was kind of like growing up on the farm where the rules were if you were nice, people liked you and you had friends. If you weren’t, you didn’t have friends.”

More:From maverick to outcast, the rise and fall of Julia Olson-Boseman in New Hanover politics

One of those eager to see Easley succeed was Norman Holden. At the time, Holden worked in the probation office and was frequently inside the courtroom. He befriended Easley, offered him advice and introduced him to sailing. Easley can still recall that first day on the water.

“We put that sail up, the boat started moving, and I thought, ‘It really does work,’ and I got hooked on it,” he recalled.

From that time on, whenever court ended early, Easley and Holden would head for boat harbor.

The Southport of the 1970s and 1980s offered few options for entertainment. Days were spent on the water, collecting clams, visiting your neighbors, and sharing meals. At the time, there were only a few restaurants. Easley recalled at Oliver’s Grill, owner Ed Oliver always knew what his customers were going to have for lunch.

“A lot of times, it wasn’t what you wanted, but that’s what he was going to give you,” Easley said, with a chuckle. “I’d go in there and say make me something, and he’d give me what he thought I ought to have.”

He also ate lunch at the Sand Fiddler quite a bit where he ordered the child’s fried seafood plate because at the time, the state per diem for lunch was only $3.25.

“If you’d tell them to hold the fries, they’d feel kinda bad about it, so they’d give you extra shrimp to make the plate look better,” he said.

Because Southport was a small village, people relied on each other. Easley found himself in need of rescue a few times. When he purchased a sailboat, he would take off on his own. He had a motor to help when the tide was against him, but it didn’t always start. Leroy Potter owned a fish house and often saved the day.

More:What happened to Wilmington's Confederate statues? City officials aren't saying much

“I’d have to wait for some boat to come by that had a radio to call Leroy’s Fish House, and he and his dog Wendy would come out there and get me,” he recalled.

Leroy, with Wendy perched on the bow of the boat, came to his rescue several times, and once suggested Easley purchase a cabin cruiser for his rides upriver.

In 1978, Easley met another young assistant district attorney named Mary Pipines, who served New Hanover and Pender counties. Friends kept introducing the two, hoping they would hit it off, and the matchmaking worked. The couple married 18 months after they met and made their home on Frink Drive in Southport. The duo became as famous for their community Hee-Haw performances, which were fundraisers for the city’s annual Fourth of July Festival, as they were for their work in the courtroom. The match would also become a powerful force on the campaign trail.

Serving his community

As a young man, when Easley thought about his future, it never included holding a political office.

“I never intended to run for anything,” he said.

But as assistant district attorney, he was passionate about bringing an end to the drug trafficking that plagued the area, and when Lee Greer decided not to run again, he encouraged Easley to give it a try.

He ran as a Democrat, he and Mary hit the campaign trail, and he was elected to the office in 1982.

As district attorney, Easley worked to cut down on political corruption, which led to several law enforcement officers and public officials being charged in connection to drug trafficking. He also saw many good, hard-working people, particularly those in the shrimping industry who had been forced to park their boat due to rising fuel costs, get caught up in crime.

“A lot of those people were offered money they’d never seen before just to offload,” Easley explained.

Prosecuting the drug traffickers was not for the faint of heart. Bill Gore, a law school classmate of Easley's who worked as a district attorney and later as chief district court judge for Brunswick, Bladen and Columbus counties, respected Easley, calling him "fearless."

More:This area near Leland’s Walmart was zoned for more housing. Why is the town changing that?

"It was like the Wild West," Gore said of the area back then. "Even when he was under threat, he continued to prosecute without any thought for himself."

As district attorney, Easley also saw a lot of rape, domestic and child abuse cases. He recalled one case where a woman had been raped, and her attacker was convicted and sentenced. Two years after his conviction, Easley received a frantic call from the woman because she had just seen her rapist at a grocery store in Leland.

At the time, the state was in crisis with its prison system, and people were getting released from their sentences early due to overcrowding. This prompted Easley to run for Attorney General, a seat he won in 1992.

Leaving Southport

As attorney general, Easley had to leave Southport and head to Raleigh.

During his two terms as attorney general, Easley was instrumental in securing a more than $200 billion settlement with the tobacco companies. The funds from the settlement created the Golden Leaf Foundation, a nonprofit organization that received a portion of the state’s funding from the settlement, which supports economic development opportunities within the state. A portion of those funds has come back to Brunswick County over the years, funding community college programs and helping cities rebuild damaged infrastructure.

As he wrapped up his time as Attorney General, Easley’s passions once again led him to seek higher office.

He knew someone was going to have to go in and raise taxes to help the state get through the budget shortfall it was facing and decided to run.

“Political ambivalence, not having to have the office, gives you a lot of power in that you don’t feel like you have to do whatever it takes to win; you can do what you think is right,” Easley explained.

His work paid off, and he was elected to his first term as governor in 2000. True to his word, Easley did raise taxes, but he didn't cut education.

In addition to a passion for education, Easley also became known for using his power of veto. He was the first governor to do so, and the first veto was signed inside the historic Brunswick County Courthouse, which was then serving as Southport’s City Hall. He would use the power of veto a total of nine times during his terms as governor.

After Easley’s second term came to end, he became the subject of an investigation for failing to report campaign contributions. The investigation began in 2009, and after a years-long court battle, Easley entered an Alford plea on a single campaign finance violation. With an Alford plea, a defendant pleads guilty but does not admit to the criminal act.

Gore said while he doesn't have any inside knowledge of what was going on with the investigation, he believes Easley made the plea just to put it all behind him.

"My impression was that he got tired of spending money on defense and wanted to get on with his life," Gore said. "I was surprised though. I thought had he continued his defense, he would have come out all right."

In the last few years, the court reviewed the matter and expunged the conviction.

Coming home

In the years since he served as the state's governor, Easley has found his way back to the courtroom. Earlier this summer, he argued a medical malpractice case, winning a large settlement for the victims.

He’s also returned to Southport, spending much of his time in his garage woodworking. For him, Southport is home.

“You’ve got to have a sense of place in your life, and you’ve got to relate to place in the form of an environment — not just the river, but the people in that environment, the sense of community,” he said.

While Easley still lends his voice to politics when needed, he doesn’t want to weigh in on the actions of any governors who’ve held the seat since him.

“Two things governors don’t like very much are a predecessor and a successor if they start doing too much talking and don’t know what’s going on,” he said. “So, any conversations I have with other governors just stay with me, and it’s important that they have that access.”

When someone spends his life in public service, people are eager to talk about leaving a legacy. But that's not something Easley thinks about or wants to discuss.

"My legacy is I don't want one," he said.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Former N.C. governor Mike Easley leans on Southport as a safe haven

money

money