DOJ watchdog: Prison staff failures preceded inmate murder of Whitey Bulger

WASHINGTON – Like most of his prior victims, James "Whitey" Bulger never had a chance.

Days before his transfer to a violent federal penitentiary in West Virginia, inmates were already buzzing about the impending arrival of the ruthless one-time leader of Boston's Winter Hill Gang whose dual role as an FBI informant made him an instant target.

In telephone calls and in emails, inmates talked openly about the celebrity prisoner about to join their ranks at the U.S. Penitentiary at Hazelton.

One inmate, noting Bulger's reputation as an informant, told federal investigators that fellow prisoners were "betting money" on how long the 89-year-old gangster would survive in the same place inhabited by rival organized crime offenders.

Less than 12 hours after his arrival, the man whose own reign of terror included gun trafficking and murder was dead. His battered body was found in a bunk, rolled up in bed covers.

Prison system problems: Top officials at troubled federal prison system recommended for more than $3M in bonuses

Four years later, details of the botched handling of Bulger's October 2018 transfer from a Florida federal prison to West Virginia were revealed Wednesday by the Justice Department's inspector general in a damning rebuke of the federal Bureau of Prisons.

"Our investigation revealed serious BOP staff and management performance failures at multiple levels," the inspector general's report concluded, citing "bureaucratic incompetence and flawed, confusing and insufficient BOP policies and procedures."

Although investigators did not find evidence to support criminal charges, at least six federal prison staffers could face disciplinary action in connection with the case.

"In our view, no BOP inmate's transfer, whether they are a notorious offender or a non-violent offender, should be handled like Bulger's transfer was in this instance," the inspector general concluded.

The Justice review comes four months after three men, including a Mafia enforcer, were indicted in Bulger's beating death in an attack that highlighted rampant violence and stunning security failures across the vast federal prison system.

More: 3 men, including Mafia hitman, charged in 2018 prison killing of Boston crime boss Whitey Bulger

More: Gangster James 'Whitey' Bulger's life and death defined by brutality

Fotios "Freddy" Geas, 55; Paul "Pauly" DeCologero, 48; and Sean McKinnon, 36, were charged with conspiracy to commit first-degree murder.

Geas and DeCologero were accused of striking Bulger in the head multiple times. The two were also were charged with aiding and abetting first-degree murder, along with assault resulting in serious bodily injury.

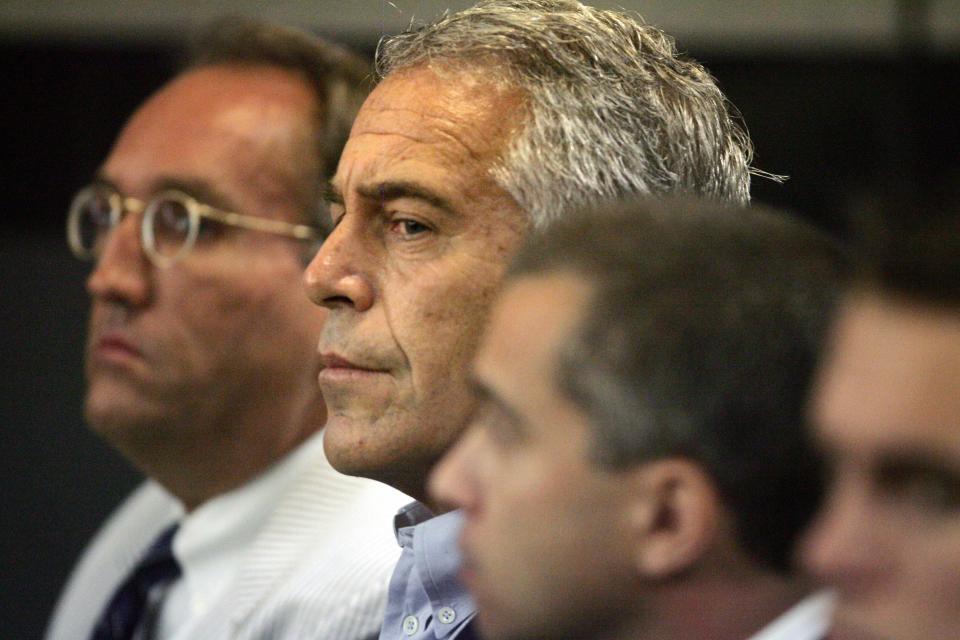

Known as one of the nation's most notorious criminals and fugitives, Bulger – nicknamed “Whitey” for his bright platinum hair – was the head of a violent South Boston crime ring known as the Winter Hill Gang from the 1970s into the 1990s.

Until his capture in 2011, Bulger also ranked as one of the country's most-pursued criminals, having managed to elude federal authorities for 16 years. At the time of his death, the one-time crime boss had grown frail and used a wheelchair while serving a life sentence for 11 murders and other crimes.

The inspector general's 65-page report highlighted Bulger's declining health in detail, concluding that prison officials also disregarded the inmate's "complex cardiac history" that required multiple hospital visits when he was ultimately moved to Hazelton, a facility that didn't offer the necessary level of medical care to deal with Bulger's condition.

Prior to his transfer to West Virginia, Bulger had been housed in the nation's largest federal prison complex in Coleman, Florida, where he had been serving a fairly uneventful term. The aging gangster was widely known to staffers there, though his risk of violence as a longtime mob boss had largely faded with his increasing frailty.

In early 2018, however, he was sanctioned for threatening a nurse, according to prison records. A staffer familiar with the incident said Bulger referred to a "day of reckoning."

The incident set in motion a prolonged effort by Coleman officials to move Bulger out of their custody, a period in which the inmate was placed in solitary confinement for eight months.

The lengthy term in solitary, according to the inspector general's report, appeared to have contributed to a decline in the inmate's mental health. During a suicide risk assessment, conducted nearly a month before his transfer, Bulger told a psychologist that he had "lost the will to live."

Yet, prison staffers persisted with Bulger's transfer.

"We were particularly concerned that the final transfer paperwork was contrary to and did not even acknowledge the clear direction" of the agency's health programs chief that Bulger was in need of a higher level of medical care than available at the West Virginia prison, the inspector general concluded.

Contrary to the security concerns shrouding the movements of other prisoners, especially high-profile inmates, Bulger's transfer and ultimate destination had become an open secret across the prison system.

The inspector general's review found that more than 100 agency officials were made aware of Bulger's transfer and that "Hazelton personnel openly spoke about Bulger's upcoming arrival in the presence of Hazelton inmates," contrary to agency policy.

"The widespread knowledge of Bulger's transfer among BOP officials made it impossible for us to determine the particular BOP employees responsible for these improper disclosures, which resulted in numerous Hazelton inmates being aware of Bulger's transfer to Hazelton days before it occurred," the report concluded.

"This knowledge among Hazelton inmates subjected Bulger, due to his history, to enhanced risk of imminent harm upon his arrival at Hazelton," according to the report.

Indeed, one prison staffer told investigators that one of two "associates of organized crime families" – Geas – was housed in the same unit where Bulger was ultimately assigned.

"The (staffer) told us that he knew in advance that Bulger was going to the unit where one of the organized crime associates was housed and 'thought' about it," the report stated. "However the (staffer) stated there was no intelligence that indicated that the two associates of organized crime posed a threat to Bulger."

The Bureau of Prisons, in a written statement, said it has been implementing "several improvements to its medical transfer system including enhanced communication between employees involved in the process, multiple trainings for personnel, and technological advancements."

"It is the mission of the BOP to operate facilities that are safe, secure, and humane," the agency said. "The BOP takes seriously the duty to protect the individuals entrusted in their custody, as well as maintaining the safety of correctional staff and the community."

Immediately after Bulger's death, federal prosecutors acknowledged they were investigating the case as a homicide.

At that time, Geas was abruptly moved to segregation pending the outcome of the inquiry. Geas was a known Mafia operative who, like Bulger, was serving a life sentence for a spate of violent crimes, including murder.

More: Attorney General ousts head of federal prison system in aftermath of Jeffrey Epstein's death

Geas and his brother were implicated in the 2003 murder of then-Springfield, Massachusetts, crime boss Adolfo "Big Al" Bruno. Geas' conviction was won largely on the testimony of informants, a role that Bulger had once embraced for federal authorities to avoid prosecution for his own violent crimes.

Bulger was found in his cell by two officers after it was noted that he had not arrived for breakfast.

More: Federal prison officials get bonuses as staffing shortages, management problems persist

More: James 'Whitey' Bulger, notorious Boston gangster, found dead in prison; homicide suspected

Finding Bulger in his bunk wrapped in covers, the officers initially believed he was sleeping. When Bulger did not respond to their presence, the officers removed his bed wrap to reveal a bloodied and severely beaten face and upper body.

"It was a beat-down," said one of the staffers who viewed the body. "It could have been done with fists or it could have been done with a lock in a sock."

The staffer referred to a popular makeshift weapon in prison in which ordinary padlocks are placed in socks and swung with force to strike designated targets.

Video surveillance showed at least two inmates going in and later exiting the cell before the body was discovered by the officers, the staffers said.

The unit was accessible, the staffers said, because cell doors are opened early in the morning in preparation for breakfast, and remain open until late afternoon, just before the evening inmate count.

Bulger's killing drew increasing attention to widespread problems within the federal Bureau of Prisons and was closely followed by the 2019 suicide of accused sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein.

Beset by persistent security, violence and staffing problems, the Justice Department in July named the longtime chief of the Oregon Department of Corrections, Colette Peters, to lead the sprawling federal prisons system.

"Hazelton's staffing during that timeframe was at an abysmal level and officers were being forced to work mandatory overtime almost every day of the week," said Justin Tarovisky, the prison union president in Hazelton, adding that local officials increasingly tapped kitchen staffers, teachers and other non-law enforcement positions to cover officer shifts. The practice, known as augmentation, "reduces supervision, and hampers the emergency response at the institutions," Tarovisky said.

Bulger’s family had previously filed a lawsuit against the Federal Bureau of Prisons and 30 unnamed employees of the prison system, alleging they failed to protect him. Bulger was the third inmate killed in six months at USP Hazelton, where workers and advocates had long been warning about dangerous conditions.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Whitey Bulger: Inmates knew of Boston mob boss' transfer before murder

money

money