'It's just like: Where are you?' Jeff Stambaugh simply vanished in the Arizona mountains

He left his cell phone charging at the campground.

He got into his Subaru Forester and drove a few minutes along a mountain road. He stopped to go hiking.

Could this have been a new life start, this impromptu trip in the Arizona wilds?

Jeff Stambaugh was 63 and seemingly free at last to immerse himself in nature whenever possible, a love he discovered growing up in York County. He was recently retired from psychology work. A bad ankle was finally on the mend.

And he didn't appear to be going out too far or long on this particular blue-sky, early-fall day.

He'd have to return for his charging phone. He left most of his belongings, including his water purifier and frame backpack, in his Subaru. He left his laptop in his tent.

He hoped to meet up with a longtime friend later.

He parked at a familiar trailhead on Granite Mountain. It was mid-morning, Sept. 28, 2022. Temperatures were nearly perfect, rising through the 70s.

He changed shoes and got out of his car. He decided which way to go.

He began walking among the evergreen juniper bushes, oaks and Ponderosa pines. Along the granite boulders and endless scrub.

He walked somewhere.

And vanished.

York County, Pa. native sought Arizona wilds

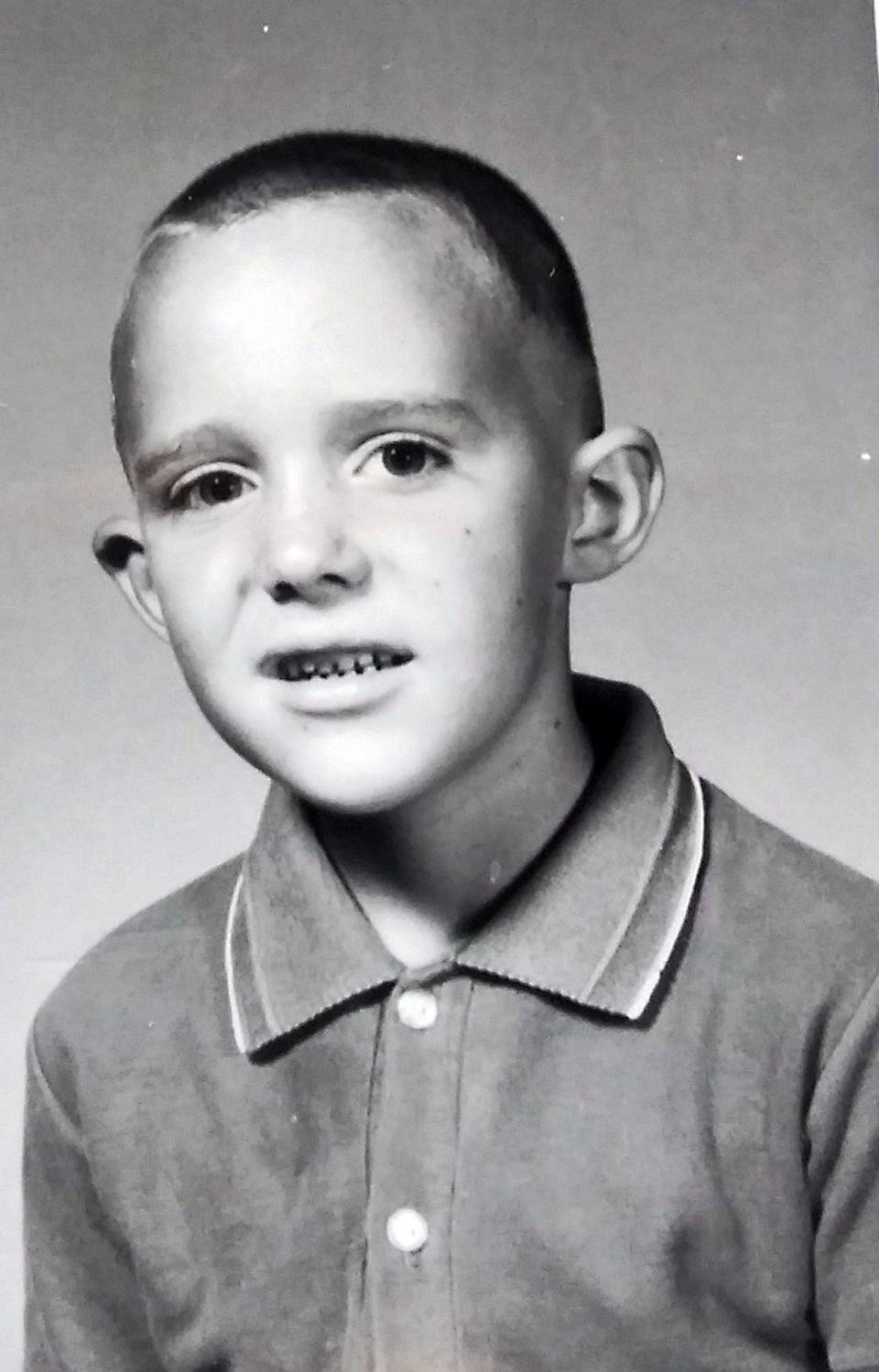

Jeff Stambaugh grew up in the Emigsville area of small-town York County, Pennsylvania. He played on the high school golf team and read voraciously. He graduated from Central York High School in 1976.

He studied at York College and earned a master's degree in psychology from the University of West Georgia. He worked in that field most of his life.

Maybe most important about Stambaugh: He learned to fish and walk the woods as a kid and seemed to live for his time exploring nature − often preferring to do it alone.

Fitting, then, that he would pack up and boldly move to Arizona some 25 years ago. The red and brown landscapes, the stark rises and falls between desert and mountain, were so magically different from everything he grew up around.

He worked at veterans' hospitals in Tucson and Prescott and enjoyed hiking the land near both. He was experienced in survival skills and gear − and enjoyed pushing limits, according to longtime friend Lucy Hall-Berry.

He'd often explore off-trail, not hesitating to cross large streams, walk ledges or even pick his way up a rock face. He carried a machete in the back of his car to cut down brush.

It only charged him more, it seemed, how Arizona can be unexpectedly dangerous to novices and experts, alike. From the debilitating heat to shifting, sliding trail rock to even the wildlife, such as snakes and bees, bears and mountain lions. The isolation of it all magnifies missteps.

"He would take that kind of risk on slippery rocks, whatever it was, just to go where regular people wouldn't go," said Hall-Berry, who lives around Prescott. "I pushed myself along with it (at times). ... There’s people who just don’t like to go on paved trails."

Her hike of a lifetime: 'It's like a part of your soul has a hole in it.' She hiked for her son and found herself

It's not uncommon for hikers in Arizona to become disoriented by the surroundings, especially if they leave a main trail. Things often spiral quickly. Dehydration, heat exhaustion and heat stroke can disable in just a few hours. The higher, rugged terrain can make footing perilous and falls potentially deadly − and complicate matters for would-be rescuers.

A 60-year-old female hiker died during a solo trek, about 30 miles north of Phoenix, a day before Stambaugh went missing. Not long before that, three Arizona hikers died in separate incidents during one tragic week − all after apparently running out of water.

In May of last year, a 74-year-old man died in the same national forest where Stambaugh hiked. He had phoned authorities to say he was lost. His body was found six days later, his dog alive and well by his side.

Stambaugh's September trip from Tucson to the Prescott area did surprise his longtime friend. He hadn't told Hall-Berry about it before phoning her from the mountain on the evening of Sept. 27. He left a voicemail message, urging her to meet him at his camp site. She said she returned the call later but did not get through.

The following day − hours after Stambaugh left his phone charging at the Yavapai Campground ranger station − she left him a note at his tent. Maybe he had decided to drive somewhere else to hike without telling anyone? That would have been like Jeff.

It was only after two more days of return visits, without contact, that she began to worry. Park officials were forced to clear out his camp site. They found his car.

He was reported missing.

The search

It didn't matter that Desirae Riggs had never met him.

She happened to be in the national forest when her friend, Hall-Berry, called in a panic. She said searchers were mobilizing quickly to look for Stambaugh. Storms were threatening that evening. Frigid air would be settling in a few days after. Time was precious.

Riggs, 43, is an avid hiker, as well. She's also a certified nursing assistant who said she can't help but care for others she doesn't know. So she immediately drove to the Metate Trailhead, where Stambaugh's Subaru was parked. She convinced a canine search group to let her tag along.

They walked a trail heading east around the mountain, continually calling out his name as they went. At one point the dogs seemed to latch onto something, a clue, possibly. But it quickly disappeared.

Meanwhile, others searched the vast area in helicopters, using infrared technology. Some rappelled from the top of Granite Mountain to look in caves and crevices and around giant boulders.

Riggs' group walked for more than two hours that first day, forced to turn back as evening fell. So many thoughts flew: how two juvenile bears in the area were blamed for killing a horse and other animals; about the unsearched, steep ravine below them; about a good friend of hers who disappeared on another Arizona mountain a few years before − to take her own life.

There are so many directions and places Stambaugh could have gone.

"I was just really thinking" Riggs said, "that he's not on this trail. ... People don’t realize how crazy-big this place is."

Over the following three weeks more than 300 volunteers and multiple law enforcement agencies searched for Stambaugh, covering an estimated 10,000 miles of terrain, according to officials with the Yavapai County sheriff's office.

Rescue teams searched with drones and on horseback and in all-terrain vehicles. They scoured a nearby lake.

Some volunteers continue to look on their own. They handed out missing-person fliers around the Granite Basin Recreation Area and downtown Prescott.

And yet, nearly four months later, not a trace of Stambaugh has been found, according to authorities and his relatives.

At first, family members wondered if he could have been abducted from the area. Law enforcement officials, however, told them they could not open an investigation without evidence of potential foul play. (Yavapai Sheriff Office officials declined to speak about the case beyond basic search-and-rescue data.)

Could Stambaugh have suffered from some medical trauma or an accident, such as a disabling fall?

Or could he have even intentionally harmed himself somewhere in the wilderness? Family members, at least, don't believe in that theory. Rather, they think the national forest may have been just the first stop on a larger trip through the West. His car was packed with clothes, jugs of water and outdoors gear. His most recent laptop searches were related to camping and weather in Colorado, Utah and other parts of Arizona.

"It was like E.T. came by and sucked him up," said Stambaugh's brother-in-law, Scott Chambers. "They've found nothing. Not a button, not a piece of clothing, not a scent."

From Delaware to the Arizona wilds

They needed to be on that same mountain 2,200 miles away.

In early December, Stambaugh's older sister, Pam Chambers, and husband Scott, flew to Arizona. They spent a week there to gather up his belongings and finalize his estate as best as they could − even without any official word of what happened to him.

They searched for something, any kind of clue, that everyone else could have missed.

The Chamberses, who live in Newark, Delaware, felt compelled to drive to the trailhead area where Stambaugh's car was found. Pam and her husband walked and prayed and tried to talk to Jeff.

Their sadness and frustration, even anger, was overwhelmed by the unknowing.

"You're standing where he was last supposed to be...," Scott Chambers said. "You look in all directions, and it's just like: Where are you? ... You stand there and shake your head and don’t know what happened."

No eyewitnesses have come forward saying they saw Stambaugh after he left the ranger station.

His sister said she does believe that he died somewhere on that mountain, most likely after an accident. Still, the lack of answers, to any kind of closure, haunts searchers, friends, family. Officials have told them that the remains of missing persons in these areas may never be found.

"It's a possibility that he just got swallowed up by nature," Scott Chambers said. "You could get lost in a heartbeat ..."

Riggs, Hall-Berry and other volunteers are planning to search again for Stambaugh on Jan. 28 − in areas of the vast mountain country they believe have been neglected so far.

"He’s not dead in my mind," Hall-Berry said. "I know the reality. But it’s a bizarre feeling. How do you determine someone is dead when you don’t have proof?"

Pam and Scott Chambers try to take some solace in recovering his belongings, saving whatever they deem important. Stambaugh was not married and had no children.

She wanted to make sure "his memories and stuff were not just thrown away. Because he would have just vanished then."

Riggs said she cannot shake thoughts of Stambaugh, day and night. He would have turned 64 on Oct. 25 − about the time searches were called off.

The unknowing haunts.

It also inspires her, she said, to become trained in search and rescue.

"I'm not going to stop until I find him because he needs to be laid rest," Riggs said. "This man had a life. He had a life he left behind. And I know he’s out there ..."

Frank Bodani covers sports and outdoor stories for the York Daily Record and USA Today Network. Contact him at fbodani@ydr.com and follow him on Twitter @YDRPennState.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: York man vanishes hiking in Prescott National Forest, Arizona

money

money