Jimmy Carter's influence in Green Bay highlighted by work after his presidency

GREEN BAY - June 7, 2002, was the last day of construction in Durban, South Africa, and Chryssy Joski, tired and coated in sweat and building dust, watched a gleeful 6-year-old boy run from room to room of his new two-bedroom house.

It was also her 19th birthday, she was more than 9,000 miles away from her Green Bay home — and approaching her to shake her hand and help celebrate the day was none other than former U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

At 77, Carter hardly looked the part of a former president. He was casually dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, his hands dirty, and he was flanked not by security detail but skilled tradesmen. They were visiting each of the 100 sites of newly constructed homes, built up from the hands of 1,500 volunteers in what Carter called a "blitz build."

"Jimmy Carter came over and shook my hand and said something to the effect of, 'We need more young people who are choosing to spend their birthdays giving to other people instead of expecting people to give to them,'" Joski said. "It's something that, even now that I'm pushing 40, I still try to do."

After serving as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981, Carter and former first lady Rosalynn began championing the work of Habitat for Humanity with the Carter Work Project, which began in September 1984. Three years later, former Schreiber Foods CEO Jack and Engrid Meng formed the Greater Green Bay Habitat for Humanity, a result of Carter putting a national spotlight on the organization.

On Feb. 18, the longest living president opted to enter hospice care at the age of 98.

With nearly a century of life under his belt, it's no surprise that the former president and Nobel Peace Prize recipient paid many visits to Green Bay, inspiring a handful of its citizens along the way and helping to break down stigmas surrounding affordable housing and charity projects.

"Former President Jimmy Carter demonstrated true compassion for humanity and sparked great dialog across the nation to take actionable steps toward addressing affordable housing insecurities that are widespread in the U.S. and internationally," said Jessica Diederich, CEO and executive director of Greater Green Bay Habitat for Humanity. "And still today, President Carter’s impact with Habitat for Humanity International has rippled through all of the affiliates."

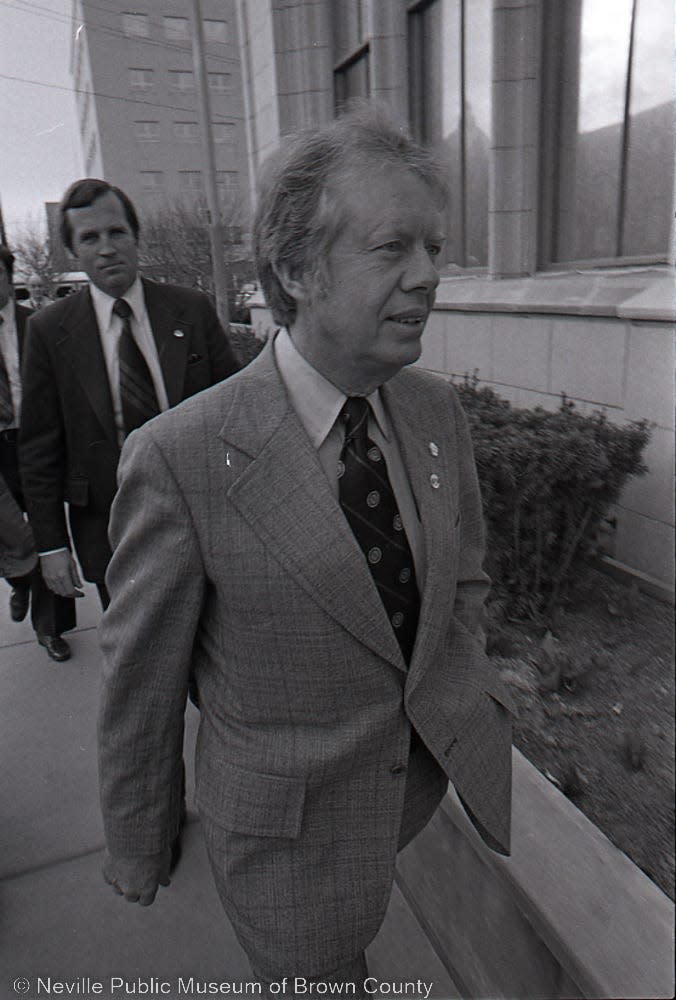

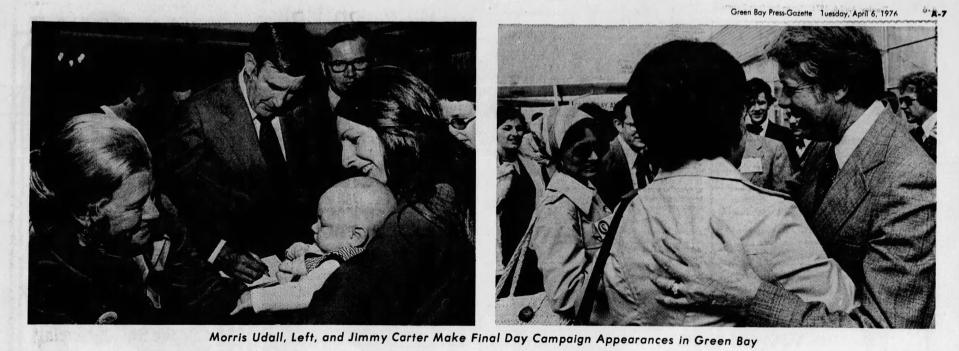

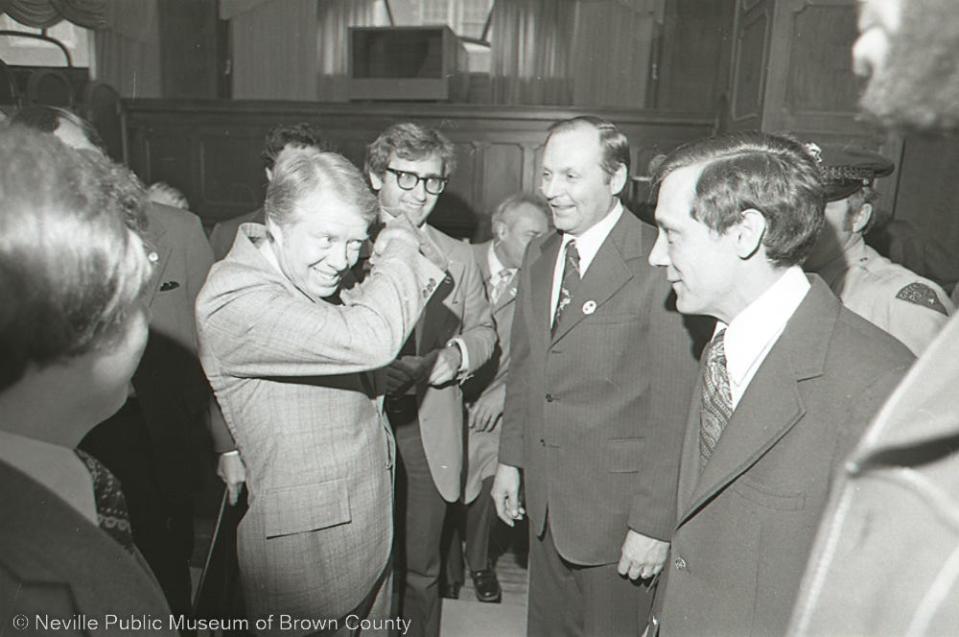

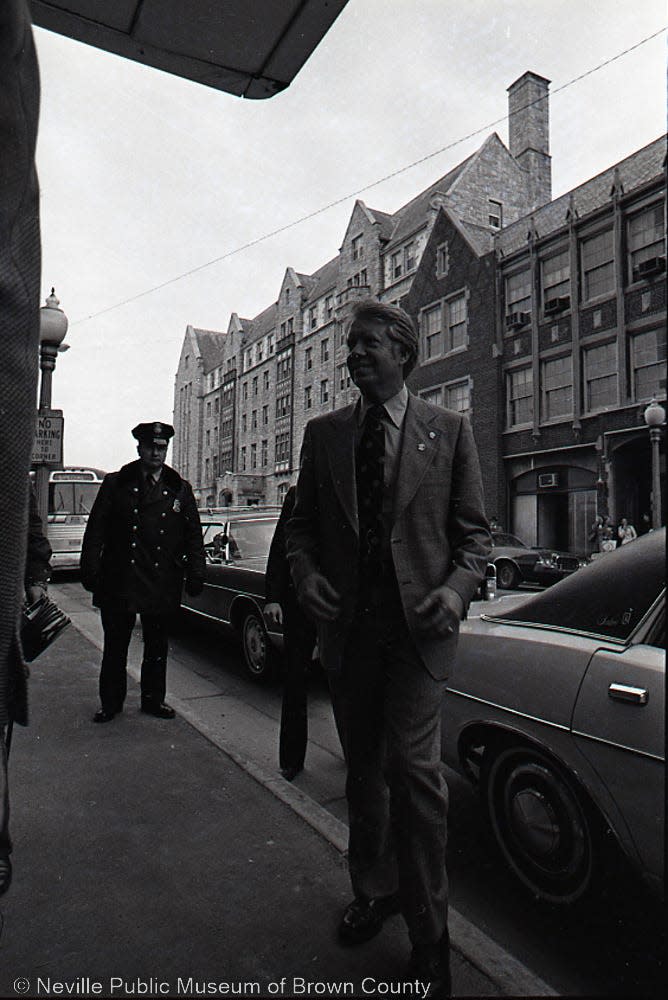

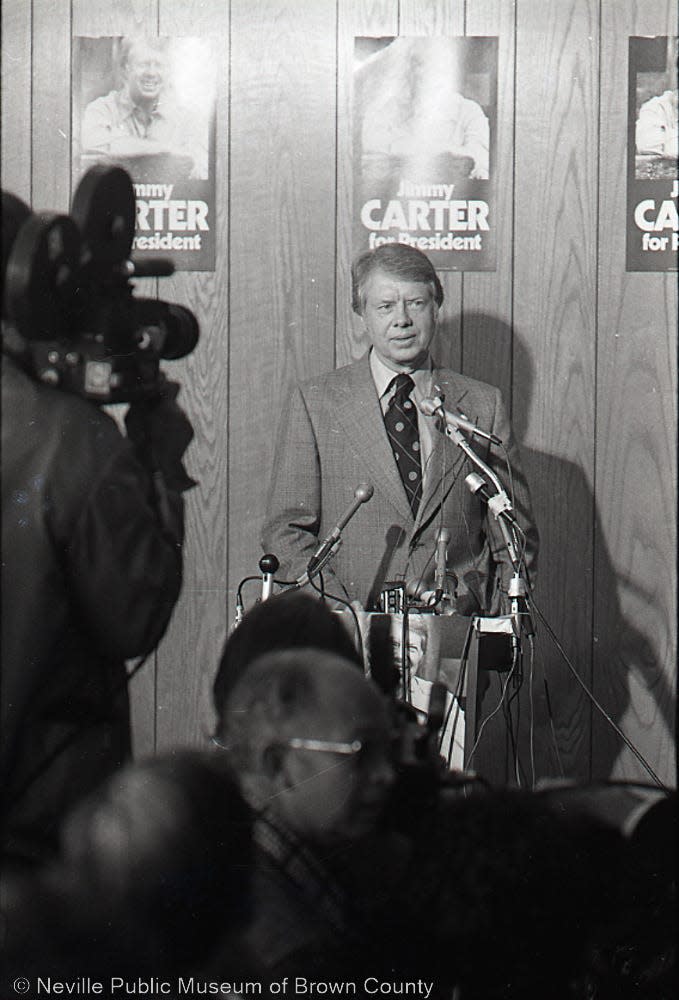

Carter on the campaign trail in Green Bay

Newspaper archives offer Carter's colorful development as a public figure in Wisconsin.

The former Georgia governor was heckled in Madison by students ahead of the spring primaries of 1976 when they flung peanuts at him, their way of refuting his liberal status. (The use of peanuts was a nod to his being a former peanut farmer and processor.) More than a decade later, Carter would take on Milwaukee's inner city, building six new homes from the site of the city's deadliest fire at the time of the article's writing in 1984.

Carter spoke at Green Bay-Austin Straubel International Airport on March 26, 1976, ahead of winning the primary less than a month later and he was captured strolling down a blustery East Walnut Street to "visit the Press-Gazette to talk with newsmen" on March 26, 1976, according to an article by then-staff writer Dale Gross.

He would visit Green Bay twice before his Wisconsin primary victory, enjoying the ornate banquet hall of Hotel Northland and shaking hands with residents oscillating between him and U.S. Rep. Morris Udall for the Democratic ticket.

On June 30, 1976, former Green Bay Mayor Michael Monfils nodded approvingly of Carter's promise to accelerate a public works employment program during the 44th annual session of the U.S. Conference of Mayors at the Milwaukee Convention Center, although Monfils pointed proudly months before to the Udall button he donned.

"Needless to say, I am very pleased with what Gov. Carter said," Monfils told the Press-Gazette then.

Visiting Carter in Plains, Georgia

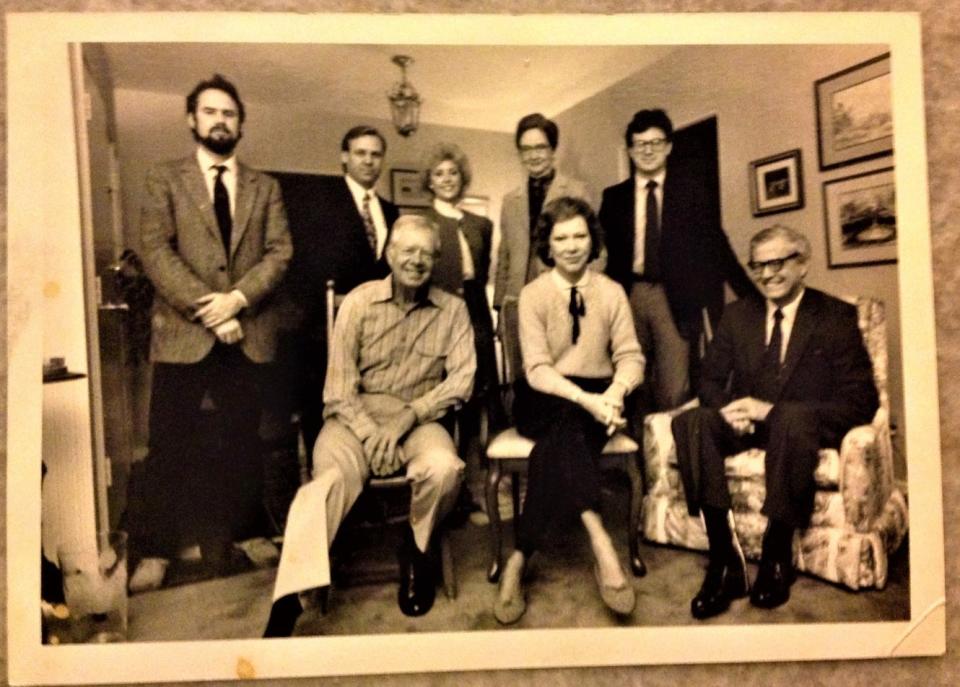

Tom Kunkel, interim president of St. Norbert College in De Pere, had a chance encounter with Carter when he was editor of the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer in Georgia a few years after Carter's presidency. The Ledger-Enquirer office was only 30 miles from Carter's home in Plains, Georgia, and Kunkel wrote him a letter asking if the staff could meet him.

Less than a week later, the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer editorial staff were on their way to Plains, a town of fewer than 1,000 people in southwestern Georgia.

"He got back to us right away, and he said, 'Yeah, come on, down.' So, half a dozen of us got dressed up one day and drove down," Kunkel said.

Kunkel described the Carters home as modest and very comfortable, "like going to your aunt and uncle's house." They sipped coffee and drank sweet tea for a few hours, talking about "everything under the sun," he said.

That experience has always stayed with Kunkel, and it showed him that, politics aside, Carter was a model statesman.

"It's always kind of neat when you find out that people you've always admired are as down to earth and authentic as you hoped they would be," Kunkel said, who had first seen Carter 10 years prior on the campaign trail.

Carter's life is 'a textbook on how to be an American statesman'

The Carter Work Project has led to 4,390 homes being built, renovated or repaired across 14 countries, motivating 104,000 volunteers like Joski to make use of their hands in far-flung regions of the world.

Brown County, although not part of Carter Work Project directly, has benefited from Carter's leadership: Habitat for Humanity's volunteers have built 131 houses for 214 adults and 384 children.

"We are so proud that we get to do the work of Habitat for Humanity in our community and strive to emulate the passion that President Carter has for lifting up our fellow neighbors, getting our hands a little dirty, and giving a family in our community strength and stability for their future by providing them the ability to purchase a truly affordable house," said Diederich, of the Greater Green Bay Habitat of Humanity.

Kunkel, reflecting on Carter's life, considers it a triumph that the peacemaking around the world, the human rights work, the voting rights he championed, and the better life conditions for low-income people, the emphasis on equity, all came after his presidency.

"It's just, well gosh, an unbelievable life well-spent," Kunkel said. "The fact of the matter is that by the time he finished being the president, Jimmy Carter's life turned out to be only half over. He basically spent the second half of his life building a textbook on how to be an American statesman."

Joski said her brief exchange with Carter over 20 years ago changed her as a person. She took to heart what he said about giving to others on her birthday. Every time her birthday rolls around, Joski donates birthday cake mix, frosting and birthday candles to a local food pantry because birthday cakes aren't in large supply, if at all, for many who rely on pantries.

In the days she painted and drilled with 1,500 others in Durban, South Africa, she could still bear witness to the ugly shadow of apartheid. Even a decade after apartheid, the houses she helped build sprang from an uninhabited mile-long strip outside the city where white South Africans lived. A majority of Black South Africans still lived on the other side of that strip, in one-room tin shacks.

She painted alongside the eventual owner of the home, a professional painter in his own right. They didn't speak the same language, Joski said, but "joy like that doesn't need a language." The spectacle of meeting Carter could happen only after Joski she could see this man's son squeal in excitement over the prospect of a multi-bedroom home.

"I'm only one person, but my contributions to that house are changing this little boy's life forever," Joski said. "I may not have changed the world, but I changed the world of that family and that little boy, and that mom and dad."

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Central Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Jimmy Carter's influence in Green Bay goes beyond politics

money

money