Inside ‘Misty,’ the Play That Puts Gentrification on Trial

Can a discussion about gentrification be entertaining? That was a question Arinzé Kene wrestled with in creating Misty. The play within a play features a sparse set, spoken word, song, and more to explore a changing London through the lens of two characters.

While one grapples with his neighborhood evolving, the other, a playwright, puts pen to pen paper detailing the laundromat turned into a “swanky” coffee shop to seeing neighbors getting displaced and more. In each character the audience sees—and can perhaps identity with—the fight to stay true to who you and find your footing as the world around you changes. Making its stateside debut at The Shed through April 2, Kene sought to create a “dynamic” work that would prompt people to “come and learn something about each other.”

‘Residue’ Shows the Human Toll of White Gentrifiers Invading Black Neighborhoods

“The play isn’t saying ‘You’re good,’ ‘You’re bad’— it’s just shedding light on what gentrification does to a place,” Kene told The Daily Beast. “I don’t want anyone to feel judged, that’s not the point of the play.”

In a Q&A, Kene and director Omar Elerian discuss the impact of COVID, bringing Misty to the United States and more. The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Omar Elerian: One of the biggest metaphors in the play is the virus, which was there way before COVID. I’m quite curious to see whether people now hear that word in a different way. Without changing anything the play has changed because it already taps into a shared knowledge and experience.

Arinzé Kene: The only thing he [one of the main characters] could describe [gentrification] as was a virus—something that is unstoppable that you can have no answer to. There was a moment in 2020 where I wanted to perform it in the midst of it all because if anything COVID has made it even more relevant.

The Daily Beast: Gentrification, like COVID, can have a disproportionate impact on a community. The story is through the lens of the specific experiences of these characters—in one case the fight to belong, in the other a fight to tell your art as you see fit. Yet, it feels universal and not necessarily pegged to a place.

Kene: Gentrification isn’t unique to London, it was happening in Brooklyn before it started happening in Hackney where I live, and this is the area that inspired me to write Misty. I remember the backlash to the Barclays Center being built and I caught wind of that from here and what that did. [That said] the play happens in the here and now and will always respond to the place it's being performed, in the time it's being performed in and who it’s being performed for.

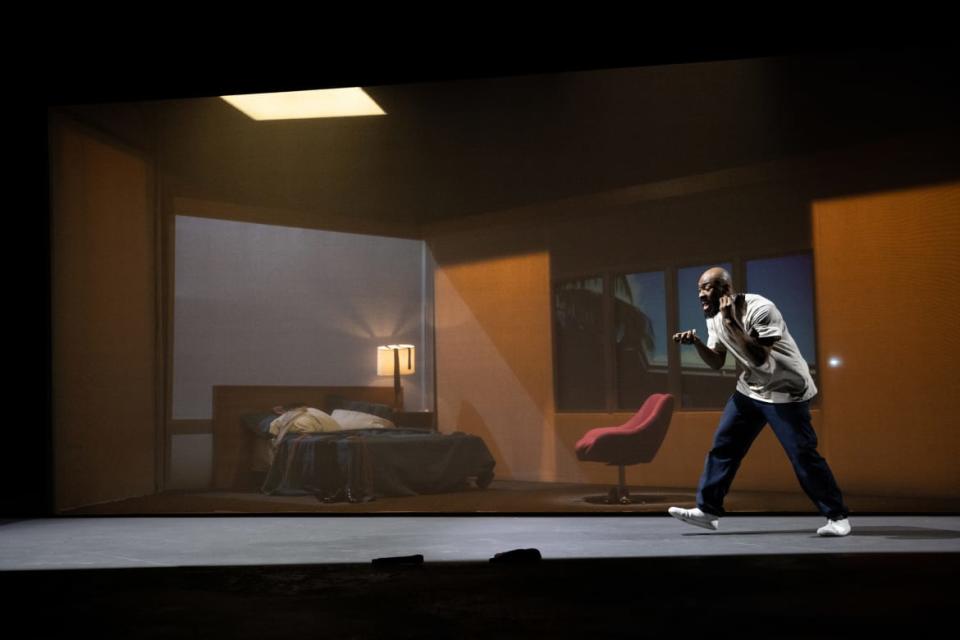

Arinzé Kene in Misty.

TDB: In terms of responding to place, as “Misty” arrives in the U.S. what were some of the key considerations, if any, in adapting the work?

Elerian: One of the big questions is will people in New York come down this rabbit hole with us? I’m less worried about the big themes like gentrification or race relations. But then there’s other little things—the humor, the taste, the music. One of the really interesting initial questions was, ‘How much do we need to make it accessible to an American audience?’ The conclusion we came to is, well, we can’t dilute it too much otherwise it will become some weird transatlantic hemorrhage. We incorporate the voices of Obama and Angelou, as well as [made] simple tweaks to the writing to make the play more aware of it being performed in front of an American audience.

Kene: Regardless of the relationship to gentrification you have, I think this story will be very familiar because everybody knows someone/family who’s either been pushed out of the neighborhood, or, who’s moved into a neighborhood that became trendy.

TDB: Speaking of things that are incorporated in the show, balloons show up periodically as a prop and depending on how you see it, subtle and yet poignant metaphor.

Kene: We walk past balloons everyday and we don’t think they’re very magical. But every now and then you pat one and you go “that was kind of cool.” For me, it represents a few things— mostly the resistance that I experience as an artist. Sometimes being a writer of color [there are] all these potholes about what you can and can’t write about. The balloon is related to the stress of trying to stay on the road because it’s really thin. The anxiety is blown into the balloon. [What the balloon means to me] depends on the night.

Elerian: As simple and mundane as a balloon is, it can be unpredictable. It could pop at any moment, it could deflate. It’s one of those things that allows you to see many things in it, people invest in it and find their own interpretations. The balloon was the artistic translation of something really boring but important. It was also fun which was inherent in the spirit of the play. I think that’s also what life is all about. It’s not one note, it’s a much more fractured, cacophonous symphony.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

money

money