Take it from a Russian – the alternative to Western democracy is far, far worse

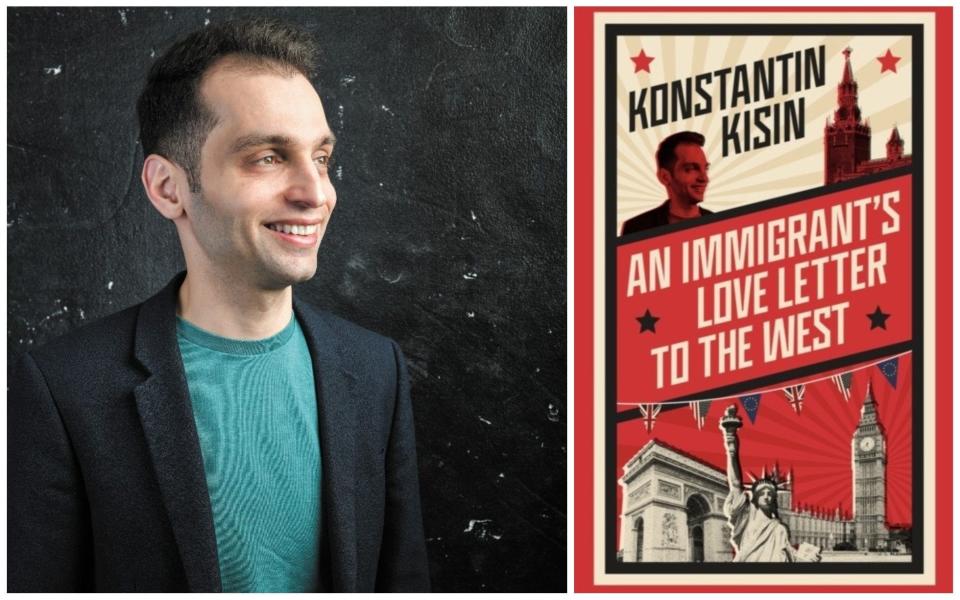

Konstantin Kisin is a young stand-up comedian and co-host of the popular online talk-show Triggernometry. There, with his co-host Francis Foster, he has interviewed scientists, authors, politicians and others, including the present reviewer. I am, I should say at the outset, an admirer of Kisin’s. He is one of an emerging generation of young, non-partisan, non-politically aligned figures who, from a bewildering array of disciplines and backgrounds, are coming together to try to think through the big issues of our time.

It is one of the most positive developments of recent years that such people are emerging. Not least because they are breaking the stranglehold that traditional media used to have on the business of ideas. Episodes of Triggernometry regularly chalk up greater viewer numbers than Newsnight or other political shows on terrestrial TV. And there are reasons for that, not least that when they say “here is an important question that’s central to our future”, they do not then devote a four-and-a-half-minute segment to it where the airtime is divided between four maniacs. They ask experts and give them time to talk.

An Immigrant’s Love Letter to the West is Kisin’s first book, and it has evolved from his career as a comedian and podcast host. Much of it has grown out of discussions he and Foster have had with their guests, and it seems from the book that as he has spoken to other people he has developed his own thinking.

In the forefront is Kisin’s own story. Born in Moscow in 1982, he grew up in the Soviet Union before moving to Britain with his family at the age of 13. His paternal grandmother was born in the Gulag, and it is this and other parts of his family history, outlined here, that have given Kisin an important insight into the society he immigrated into, as well as the one he left. For he has, all his life in the West, seen around him people who are used to their luck, expect it, take it for granted and – in some cases – end up spitting on it.

This attitude is not given to Kisin. Despite being a very funny man, he also has what so many Russians have: what Miguel de Unamuno described as “the tragic sense of life”. It gives him an important perspective on the West at a time when the West would appear to be throwing away so much of what it has achieved. Not least the freedom of speech and thought which Kisin had not experienced in the Soviet Union but had at least expected to find in the West.

Like many other things expected here, he found that precisely such principles were up for grabs. Kisin himself has made headlines in the past when he was asked to sign a form before a comedy gig promising that he wouldn’t say anything that might upset anyone in the crowd: almost a definition of how not to entertain an audience. Groupthink is another of the things which Kisin found in the West without expecting to. As he says at one point, “If there is one thing my Soviet childhood taught me, it’s that subscribing to someone else’s ideology will always inevitably mean having to suspend your own judgment about right and wrong to appease your tribe. I refuse to do so.”

He organises his book around a number of key themes, including chapters on the ways in which language can be used to conceal truth and on why we need journalists, not activists. As he says at one point in a plea to journalists, “The media … is not yours to co-opt or use to spread propaganda. You are merely stewards of the industry.” Kisin gives examples of the heroes of modern journalism, not least Anna Politkovskaya, murdered by the Russians in 2006 for exposing what Putin and his cronies did not want the world to know. Kisin is right to feel a certain sickness of stomach at the way in which so much journalism in the West has ended up wasting the opportunities of freedom.

Towards the end, he wisely quotes the Soviet defector and KGB operative Yuri Bezmenov, who gave a still-famous television interview in the 1980s in which he explained how the Soviets were attempting to subvert the West. It was not just a military campaign, he pointed out. There was a specific effort by the KGB to engage in psychological warfare of a seemingly subtle kind. For instance, he explained the effort to “change the perception of reality for every American to such an extent that despite the abundance of information, no one is able to come to sensible conclusions in the interest of defending themselves, their families, their community and their countries. It takes only between two and five years to destabilise a nation.”

Much of that seems horribly familiar today. And Kisin has practical suggestions not just on how to push back against the destabilisation of Western societies, but on how to try to impart to young people today a sense of perspective, so that in time they may see that whatever the downsides of free, free-market democracies, they are nothing compared with the downsides of all the alternatives.

There are occasional infelicities – such as a habit, which occasionally “triggers” me, of explaining that which either shouldn’t be explained or shouldn’t be cited. So we have “Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy” and “1984’s Winston Smith”. But these are tiny quibbles. Kisin has written a lively and spirited book defending the society he is grateful to have found himself in. If I can return the compliment, we are lucky to have him.

Douglas Murray’s The War on the West is published by HarperCollins. An Immigrant’s Love Letter to the West is published by Constable at £18.99. To order your copy for £16.99 call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books

money

money