How Ruth Bader Ginsburg paved the way for equality in personal finances

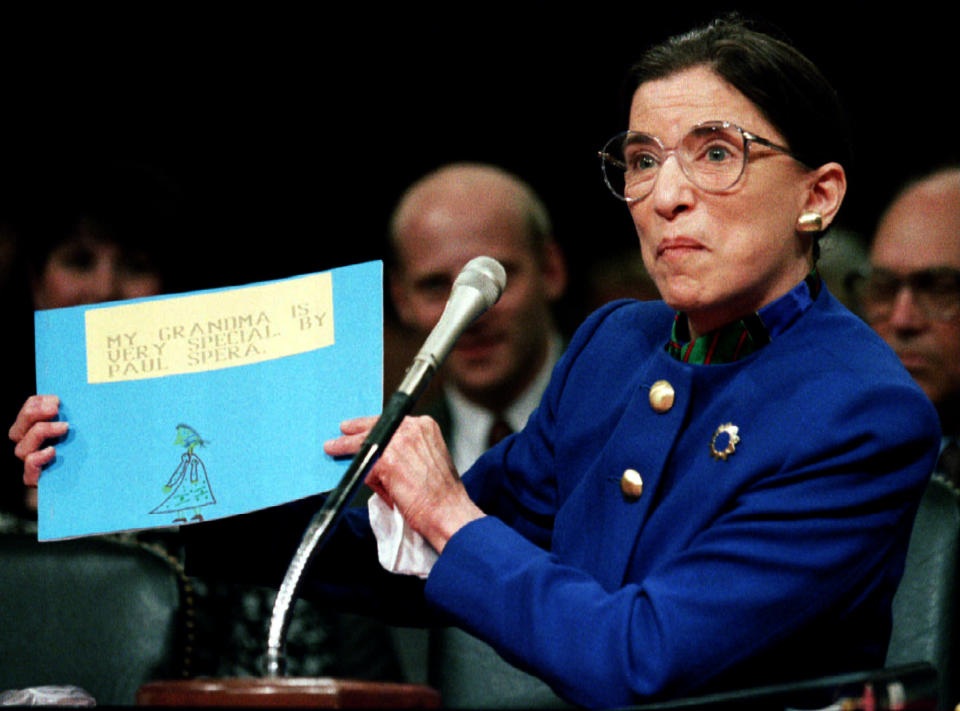

While often seen as a champion for women’s rights, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg also strengthened personal finance opportunities for women and men.

“Justice Ginsburg impacted many aspects of personal finance, not only as a Supreme Court Justice, but perhaps even more so in the earlier phases of her career,” said Nicholas Tzoumas, president of Clearscope HR, an insurance and human resources brokerage firm. “The biggest impact is that she paved the way for everyone to view themselves as an active participant in their financial dealings.”

A cofounder of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, Ginsburg helped to lay the case law foundation for sex discrimination, earning her the nickname: “Thurgood Marshall of gender equality law.”

“She was a lion in the push for equality,” Tzoumas said.

The case that started it all

One of her earliest contributions was the court case, Reed v. Reed in 1971. Sally Reed, whose son had committed suicide, was unable to manage her son’s estate due to Idaho law, which specified that males were preferred over females to administer estates.

Read more: How simply getting a credit card allowed women to eventually build wealth

Ginsburg, working at the American Civil Liberties Union alongside Mel Wulf, helped write a brief on how gender discrimination was at play.

According to the National Women’s Law Center, what made Ruth Bader Ginsburg unique among advocates was that her arguments “marked the first time in history that the Court applied the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to strike down laws that discriminated against women.”

Ginsburg herself noted that in an ACLU statement.

“It represented the first time ever in the history of the country that the Supreme Court had said yes to a woman,” she wrote, “the first time the court recognized women as victims of discrimination.”

After that, other cases — such as Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld and Frontier v. Richardson — drew upon Reed v. Reed. Hundreds of laws were also changed when Congress pored through the provisions of the U.S. Code and changed those that classified on the basis of gender.

‘The champion of the rights of women to sign a mortgage without a man’

Personal finance experts also noted how Ginsburg’s contributions helped women eventually build housing wealth. Ginsburg's work in highlighting how society was impartial to men in regards to personal finance matters, specifically the Reed case, helped build solid ground for the Equal Credit Opportunity Act passed in 1974.

The act made it unlawful for creditors to discriminate against applicants on the basis of their race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status or age. Women, therefore, were able to get credit cards and mortgages without having a male co-signer at their side. They could build credit history of their own, which opened many financial opportunities.

“Ruth Bader Ginsburg will forever be remembered in American history as the champion of the rights of women to sign a mortgage without a man and the right to own a bank account without a male co-signer among many other accomplishments.” Ogechi Igbokwe , founder of OneSavvyDollar, millennial personal finance platform. “We’re already dealing with the gender wage and wealth gap, but it could have been much worse.”

Igbokwe talked about how this affected her own experience as a 21-year-old immigrant in the United States who purchased her first real estate property.

“This is important and very personal to me because today, I'm an unmarried woman and a real estate investor,” Igbokwe said.

Read more: Here's how far women have come in the workplace and how far they need to go

Even the most basic financial transaction — opening a bank account without a man — would be off-limits to women if not for the earliest contributions from Ginsburg.

“This was a game changer,” said Andres Garcia-Amaya, founder and CEO of Zoe Financial, an advisory firm. “As a champion for empowering women’s relationship with their finances, RBG made it possible for women to be financially independent from their male counterparts.”

Paving the way for gender equality in secondary education

Ginsburg also was one of the decisive votes in United States v. Virginia in 1996. In that case, the U.S. had filed a lawsuit against the then all-male Virginia Military Institute for not admitting female students.

She wrote the majority dissenting opinion, stating that gender equality was a constitutional right and that the admissions policy violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which states that those “similarly situated must be similarly treated.”

She wrote in her opinion that “generalizations about ‘the way women are’, estimates of what is appropriate for most women, no longer justify denying opportunity to women whose talent and capacity place them outside the average description.”

Today, about 14% of the student body at VMI is female.

‘No longer are subject to this ripple effect of gender discrimination’

Ginsburg’s own life experiences helped shape her views on equality.

Even though she was tied for first place in her 1959 graduating class at Columbia University, Ginsburg was unable to secure a job at a leading New York law firm or a Supreme Court clerkship. One Supreme Court judge told her he didn’t hire women.

While at the ACLU, she also represented teachers who had to give up their jobs after becoming pregnant. She herself had hidden her second pregnancy while a professor at Rutgers because she worried she could lose her position.

“Because of RBG, women no longer are subject to this ripple effect of gender discrimination for education, getting a job, advancing their career, and fulfilling their full earning potential,” said Katharine Perry, certified financial planner at Fort Pitt Capital Group.

She also presided over cases, dealing with women in the workplace. In the 2007 case Ledbetter v. Goodyear, Lilly Ledbetter sued Goodyear Tire & Rubber company when she discovered her male colleagues were getting paid more than her.

Goodyear had said Ledbetter’s lawsuit was irrelevant as the 180-day window to file a complaint had passed. While the court did not rule in Ledbetter’s favor in a 5-4 decision, Ginsburg wrote the dissent, highlighting the inequities.

“The Court’s insistence on immediate contest overlooks common characteristics of pay discrimination,” Ginsburg wrote. “Pay disparities often occur, as they did in Ledbetter’s case, in small increments; cause to suspect that discrimination is at work only develops over time.”

A voice for men, too

But Ginsburg’s work for equality wasn’t limited to women.

In Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld in 1975, Ginsburg, representing a widower, argued in front of the Supreme Court how men who lost their wives should be entitled to equal Social Security survivors’ benefits as women who lost their husbands. She won that case.

She also represented Charles Moritz in 1972, who was denied claiming a caregiver’s tax deduction for his mother because he was an unmarried male.

The Supreme Court ruled against the Internal Revenue Service and for Moritz, saying the gender classification was "an invidious discrimination and invalid under due process principles. It is not one having a fair and substantial relation to the object of the legislation dealing with the amelioration of burdens on the taxpayer."

The court also cited a previous Ginsburg case — Reed v. Reed.

Dhara is a reporter Yahoo Money and Cashay. Follow her on Twitter at @Dsinghx.

Read more:

‘Gone in 90 minutes:’ Rental Assistance is quickly running out for struggling renters

‘Not a rent holiday’: Trump’s new eviction order leaves renters on hook for back pay

Coronavirus: Trump administration attempts to prevent evictions using CDC quarantine authority

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance and Yahoo Money

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.

money

money