Homeless, delusional defendant sent to prison for life shown mercy by Miami judge

Jared Stephens, a homeless and mentally ill man who committed an inexplicable crime, shouldn’t spend the rest of his life in prison, a judge ruled Monday.

Miami-Dade Circuit Judge William Altfield undid a sentence handed down five years earlier by a different judge, who sentenced Stephens to a minimum of 150 years — with 120 days in jail for good measure. Stephens’ delusional behavior, before and during his trial, had stymied his defense.

But the new disposition is not a get-out-of-jail-free card: Under the new sentence, Stephens faces 10 years, with credit for time served, followed by 11 years of probation— on the condition that he spend the first two years of that probation in mental health facilities. By the end of the second year of probation, he will be eligible to move to Arizona, where he can live with his family.

This timetable potentially frees Stephens from prison in July 2025, 140 years sooner than his original release date of July 4, 2166, under the sentence meted out by Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Veronica Diaz, one that shocked defense attorneys, prosecutors and court observers alike.

In court Monday, Altfield signed off on an agreement between Stephens’ attorney and state prosecutors to drastically shorten the 32-year-old’s stay in the Florida prison system.

Stephens was convicted of several counts of a serious crime: having pornographic images of children on his laptop. The strange circumstances of Stephens’ arrest, together with his outlandish behavior in the courtroom, were indicative of a person in the throes of a mental health crisis.

His refusal to cooperative with his lawyers, meantime, made it impossible to document his troubled childhood or bring in family members to speak on his behalf.

In September 2016, Stephens, then 25, attempted to walk out of a Best Buy in Sweetwater with a laptop he hadn’t paid for. When confronted, Stephens pulled his own laptop out of his backpack and declared, “Look, I have child pornography!” He then sat on the floor and perused pornographic images of children until police arrived and arrested him.

The state originally offered him a plea deal of three years in prison, as well as treatment in a program for “mentally disordered sex offenders.”

Estranged from family and uttering gibberish in open court, Stephens refused to cooperate with his attorney and rejected the offer. He was convicted, and the judge sentenced him to 150 years — 129 years longer than the 21-year sentence recommended by the prosecution. It was also significantly greater than the typical sentence for possession of child pornography.

Diaz did not explain the lengthy sentence at the time. However, when she denied a motion to correct the sentencing in May 2019, she stated that the sentence was “legal” and a jury of his peers had found him guilty.

After years of no contact, Stephens wrote his mother a letter, informing her of his legal woes. Stunned, she and other loved ones from around the country came to Stephens’ aide, testifying on his behalf at various hearings to amend his sentence.

Fan Li, a new defense lawyer, became involved in the case shortly thereafter, and, equipped with more information about his client’s background and mental health struggles, argued that Stephens needed treatment rather than a life behind bars.

Previous attempts to amend Stephens’ sentence were unsuccessful. Monday’s hearing was Stephens’ last resort to have a life outside of a prison.

Stephens’ attorney and state prosecutors originally shared the outline of the agreement during a hearing in April. Judge Altfield raised no objections to the shortened sentence but declined to rule on the motion until all the details were finalized.

He did, however, note his concern that Stephens’ mental health might deteriorate further in prison if he does not receive treatment. Both the state and Stephens’ attorney said that although receiving treatment while incarcerated is not a condition of the agreement, the option is available to Stephens.

Miami-Dade County Judge Steven Leifman, instrumental in setting up Miami-Dade’s mental health court, appeared in the case as a witness. He stated that once Stephens is free from prison, he will be able to receive the treatment he needs — and in a safer environment.

Stephens, who did not attend Monday’s hearing or the hearing in April because he requested to be returned to prison, is unlikely to participate in any treatment offered within the prison system due to what his attorney described as past mistreatment.

During the April hearing, Li described what he called one example, which involved the disappearance of all of Stephens’ belongings, including an iPad, and the Florida Department of Corrections’ claim that there is no record of him ever having owned any of it. Li said Stephens used the iPad to listen to meditation tapes, a way to keep occupied while avoiding some of the prison system’s harsher realities.

Stephens’ mental health struggles were clear at the outset of trial. He informed the court, falsely, that he was facing federal treason charges for crimes against humanity in Central America. After four months of treatment and a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the court deemed him competent and the trial resumed.

Hurdles for his defense team didn’t end there. None of Stephens’ family and friends even knew he was on trial because he stopped responding to their messages years before. With no loved ones to speak on his behalf, combined with Stephens’ lack of cooperation, Stephens’ attorney at the time was unable to present any mitigating factors that would demonstrate to the judge why she should show mercy.

She didn’t.

The jury found Stephens guilty of 32 counts of possession of child pornography. In addition to the 150-year sentence, Diaz tacked on an additional 120 days in the county jail for theft and disorderly conduct. Around then, Stephens contacted his mother, who provided an explanation of why Stephens might have fallen into a cycle of mental illness and homelessness.

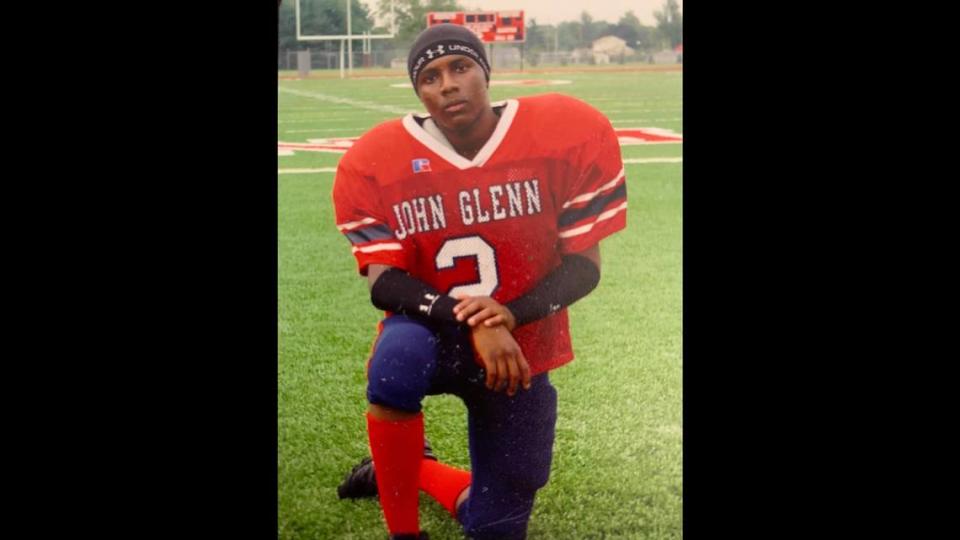

When Stephens was just 9, he survived a fire that claimed the lives of his two younger brothers. The tragedy made the local papers. His loved ones say he blamed himself and never truly processed his shock and grief. A star wrestler in high school in Southfield, Michigan, he began experiencing mental health troubles in late adolescence — derailing his career as a college wrestler at Arizona State University.

His attorneys presented this new information to Judge Diaz during a series of hearings to amend or appeal his sentence. She was unmoved. Only when a new defense attorney and judge became involved was Stephens’ plight reconsidered. After initially resisting a change in the sentence, the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office agreed to the plan that was approved by Judge Altfield during Monday’s hearing.

Judge Altfield noted that, while all parties agreed to mitigate Stephens’ sentence, he still needs to speak with Stephens to inform him of the terms of his probation. Since Stephens is in state prison, this will be done via zoom or telephonically during a status conference on July 12.

He also said that any violation of his probation must be done willfully and knowingly. Thus, if Stephens were to experience a mental health episode during a potential violation, he has faith that the court would take that into account and issue a just resolution.

money

money