Faded black and white photo inspired park ranger to explore hidden history of the Buffalo Soldiers

Activist Marcus Garvey once said, "A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots." It's why Shelton Johnson, often called "the National Park Service's best-known ranger," has devoted his life to uncovering the hidden history of the Buffalo Soldiers.

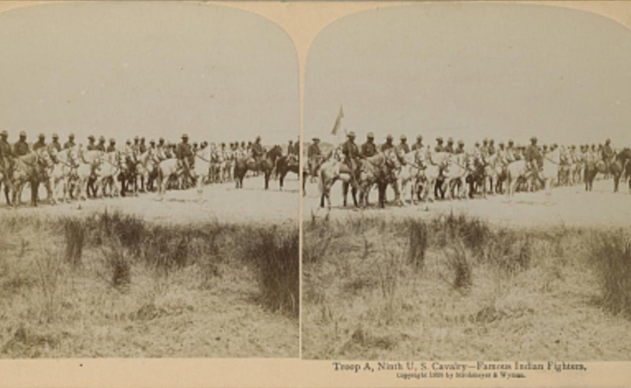

He told AccuWeather it all started with an old photograph he found in the archives at Yosemite National Park where he has worked as a park ranger for almost three decades. The faded black and white photo shows five Black men sitting astride horses in the park.

It was the earliest photo of African Americans in Yosemite Park in an official capacity and was taken in 1899. "This right here is the image that changed my life," Johnson explained in a PBS special on the Buffalo Soldiers in 2009. Before discovering that photo, he hadn't realized that African Americans had anything to do with the history of the national parks.

"It's like, you know, Lewis Carroll, Alice In Wonderland," Johnson explained to AccuWeather of his quest for more information after discovering the photo. "You know you go through the little rabbit hole, the deeper you get into the history, the more profound the history actually becomes."

Johnson, an African-American man who was born in Detroit, experienced a deep connection to the men who, like him as he would discover in his research, made the journey across America, ending up in an incredible wilderness which, in his community, was -- and remains -- a rarity.

|

"No one that I knew growing up in Detroit had ever been to a national park, had ever been to even a rural state park for that matter, it was all an urban experience."

Johnson first saw the national parks as a child flipping through issues of National Geographic, but it wasn't until 1984, when he was a graduate student in poetry at the University of Michigan, that Johnson applied for the job that would change his entire life trajectory: He signed up to be a dishwasher at Yellowstone's Old Faithful Inn.

"I remember having the thought that I couldn't think of any African-American writer or artist that was associated with the American Frontier," he recalled. "And so I thought, 'Boy, there aren't very many African Americans who write about the experience of wilderness, and I know about the idea of wilderness because I was a lit major so I had to read [Henry David] Thoreau, I had to read [Ralph Waldo] Emerson, I had to read the Lake District poets, so I'm already well-versed in that,'" he recalled. "But from an Afro-centric perspective, it was kind of a blank canvas in terms of the whole idea of wilderness."

Literature is one thing, but Johnson was wholly unprepared for the intense physical confrontation with nature when he stepped off the bus into the vast wilderness of the American west. It was an awakening.

"I was home," he said. "I fell in love with being in the wilderness."

He experienced an intimate connection to the vastness of the sky, the wind, towering mountain ranges, trees, rivers, and animals. It was then, he said, that he realized that although Detroit was where his family was, the wilderness was his true home.

It's a feeling he is passionate about and has endeavored to impart to other African Americans during his long tenure as a park ranger, first at Yellowstone, then at Grand Teton. Eventually, he landed at Yosemite where he has been working for the past 27 years.

"There's all these African Americans who feel that national parks are not a Black thing. National parks," he said, can be thought of as "not something that we do."

Surveys of national parks show that people of color represent a tiny fraction of visitors. Less than 2 percent of visitors are Black. Less than 5 percent are Hispanic, and 5 percent are Asian. Additionally, NPS employees are about 83% white, according to National Geographic.

Johnson says that despite some major strides forward in civil rights, visiting a national park isn't necessarily viewed as a "safe thing to do" because there hasn't been enough space and time from the days where people of color were not allowed in many public spaces.

"We are still living in the past, when it was unsafe, up until the '50s, into the '60s. Many of those 'sundown towns' had those signs up saying, 'Don't come in here,' up until the '70s," Johnson said. "And in that time, you just could not convince African Americans to be on the road because even if you have the thought of, 'Oh, I would love to see a glacier, I would love to walk along the edge of the Grand Canyon,' the next thought would be: 'What states do I have to pass through to get there?' It's that the journey itself was so filled with dangers that African Americans perceive, that Euro-Americans are oblivious to because those dangers are not specific to them."

It's for this reason that Johnson delights in the surprised reactions of African Americans who visit Yosemite when he shares not only his own story of being one of the very few Black park rangers, but the incredible role of the Buffalo Soldiers that has largely been forgotten. "When you're in front of a group of African Americans and you're saying that some of the first rangers in the world were African American -- their eyes, just ... They're like this."

Johnson widened his eyes, enacting surprise and rapt attention. The man can hold attention. He's been speaking passionately about the Buffalo Soldiers for decades. He's even written a book about their incredible lives.

|

His determination to keep the story of the Buffalo Soldiers alive has garnered attention from the likes of Barack and Michelle Obama, who visited Yosemite in 2016. He was featured in the Ken Burns documentary National Parks, America's Best Idea and Johnson even convinced Oprah Winfrey and Gayle King to camp at the park in 2010 and listen to him tell the story of the Buffalo Soldiers. Often he impersonates Sgt. Elizy Boman, bringing life to, in vivid detail, an actual soldier who served in Yosemite National Park in 1903 and 1904.

Although more than 100,000 African Americans fought for the Union in a segregated military during the Civil War, the Buffalo Soldier regiments weren't formed until 1866. More than a thousand young, African American men, mostly inexperienced and uneducated in their teens and early twenties, headed west to serve in the U.S. Army.

"So, when I started, I didn't have a single name to associate with any specific buffalo soldier. Now I have over 500 names ... This storyline is just, it's replete with drama. From the time they were born to the time they died, every day there was not a certainty that they were going to survive. Just because of the virulent racism that existed at that time."

The Buffalo Soldiers mainly came from the Deep South. Hundreds of young African-American men who would rather leave their homes in the South and take their chances amid the deadly weather on the Plains during a time when the American government was engaged in ongoing conflicts against various Native American and First Nation tribes; numerous battles that occurred in North America from the time of the earliest colonial settlements in the 17th century until the early 20th century.

|

Although it was a time filled with great expectations and hope, Reconstruction in the South was also an era of voter suppression, Jim Crow segregation, and the explosion of white supremacist ideology with the rise of organizations like the Ku Klux Klan.

"It was just a dangerous proposition. I mean things had to be incredibly bad for you to even risk that undertaking, but it's just that things were that bad," Johnson told AccuWeather, explaining the decision of hundreds of young African-American men to enlist in the army of a government that still did not acknowledge their humanity.

"So they did risk that undertaking because they would say, 'What could be worse than where I am right now, where someone could kill me just for being me? I've done nothing, but they could end me on a whim.'"

There are several stories about how the men acquired their famous name, but most historians agree it was the Plains Native Americans who ultimately dubbed them Buffalo Soldiers.

|

"The Kiowa, the Comanche, the Apache, their antagonists or the Native peoples that they were fighting, when they were in close-quarter combat saw that the hair on the heads of the soldiers was just like the cushion between the horns of the buffalo. So they began to call them Buffalo Soldiers," Johnson told AccuWeather.

Another theory holds that it was so cold on the Western frontier in places like Nebraska that they would wear these massive coats made of buffalo fur. "Because of their dark skin and their wooly hair you couldn't tell sometimes where the buffalo ended and the man began," Johnson said.

Whatever the reason, the name stuck and the African-American regiments formed in 1866 became known as Buffalo Soldiers.

|

The soldiers were tasked with capturing cattle rustlers and thieves, protecting settlers, stagecoaches, wagon trains, and railroad crews along the Western front. Mainly, they were assigned to help control the Native Americans of the Plains who were frustrated by being forced onto reservations after broken promises by the federal government.

The irony of one minority group aiding in the removal of another minority group isn't lost on Johnson. "The two groups that have the most [in] common were exactly the two groups that were at war with each other. Black people were aiding and abetting the genocide of indigenous people."

Although historians have documented the time the Buffalo Soldiers spent on the Western frontier, their service in the nation's first national parks has nearly been forgotten.

|

As David Schechter notes for ABC 8, "When parks only promote the stories of whites, we erase the contributions of minorities."

James Mills, a journalist and activist, echoes the sentiment. In an article for National Geographic about what the National Park Service is doing to combat racism he wrote that the contributions of many pioneering minorities have been left out of history.

Men like Charles Young who, despite being born into slavery, became the third African-American to graduate West Point. He was the first Black national park superintendent and led the Buffalo Soldiers in helping to establish Yosemite Park.

"I'd been to Yosemite dozens, if not hundreds, of times and here I am in my mid-40s hearing this story for the first time," Mills told Schechter. "And it kind of occurred to me that if I hadn't heard the story, based on my background that means that millions of people hadn't heard this story either."

|

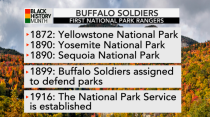

It's why Shelton Johnson says he isn't ready to retire. He told AccuWeather that after the creation of Yellowstone in 1872 and Yosemite and Sequoia in 1890, the U.S. government realized a police force of some kind was needed to defend the national parks from poachers and timber thieves. And so it was, that the Buffalo Soldiers became some of America's first park rangers even before the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916.

"Over a decade before the National Park Service was created and during the height of Jim Crow, the sons and grandsons of enslaved people forced to work lands they could never own under slavery found themselves the official guardians of sacred lands held in common to all Americans for all time."

Johnson says their groundbreaking accomplishments have all but been forgotten. They battled wildfires, stopped poachers and timber thieves, completed construction of the first usable road into Giant Forest, and built the first trail to the top of Mt. Whitney, the tallest peak in the contiguous United States, in Sequoia National Park.

They also built an arboretum in Yosemite National Park near the south fork of the Merced River in 1904. The NPS notes the arboretum is considered by some to contain the first marked nature trail in the national park system.

|

Many young men lost their lives as a result of the extreme weather conditions they endured.

"I mean you're out there and it's zero degrees or five degrees above zero, you're on horseback, it's the middle of a blizzard and you're trying to track someone," Johnson marveled. "It's just less than ideal circumstances."

Despite facing blatant racism and enduring brutal weather conditions, the men earned a reputation for serving courageously. According to history.com, "Buffalo soldiers had the lowest military desertion and court-martial rates of their time. Many won the Congressional Medal of Honor, an award presented in recognition of combat valor that goes above and beyond the call of duty."

|

Johnson says African Americans were there at the very beginning of what would eventually become a global park movement. From the creation of Yellowstone, Sequoia and Yosemite in the late 1800s, there are now more than 4,000 national parks around the world.

"We were there at the beginning," Johnson emphasized and, invoking the first book of the Bible, added, "We're not a latter-day edition, we are a Genesis. So, imagine reading the Bible waiting for your section to come out, you're waiting for you to be mentioned in the Bible, and then suddenly you tell people, 'We were there in Genesis!' We're at the beginning of the park movement."

The park ranger says there's a prevalent misperception that the Civil Rights Movement began with Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. He says it began long before that pivotal moment.

"The Civil Rights Movement began the first time an African American wore the uniform of his country and risked his life in service to a nation that did not acknowledge his humanity."

money

money