Hall of Famer Larry Doby broke barriers in baseball and left lasting legacy in Montclair

Yogi Berra, called “forgotten” in the new documentary about his Yankees career, isn’t the only iconic-but-overlooked baseball player who called Montclair home.

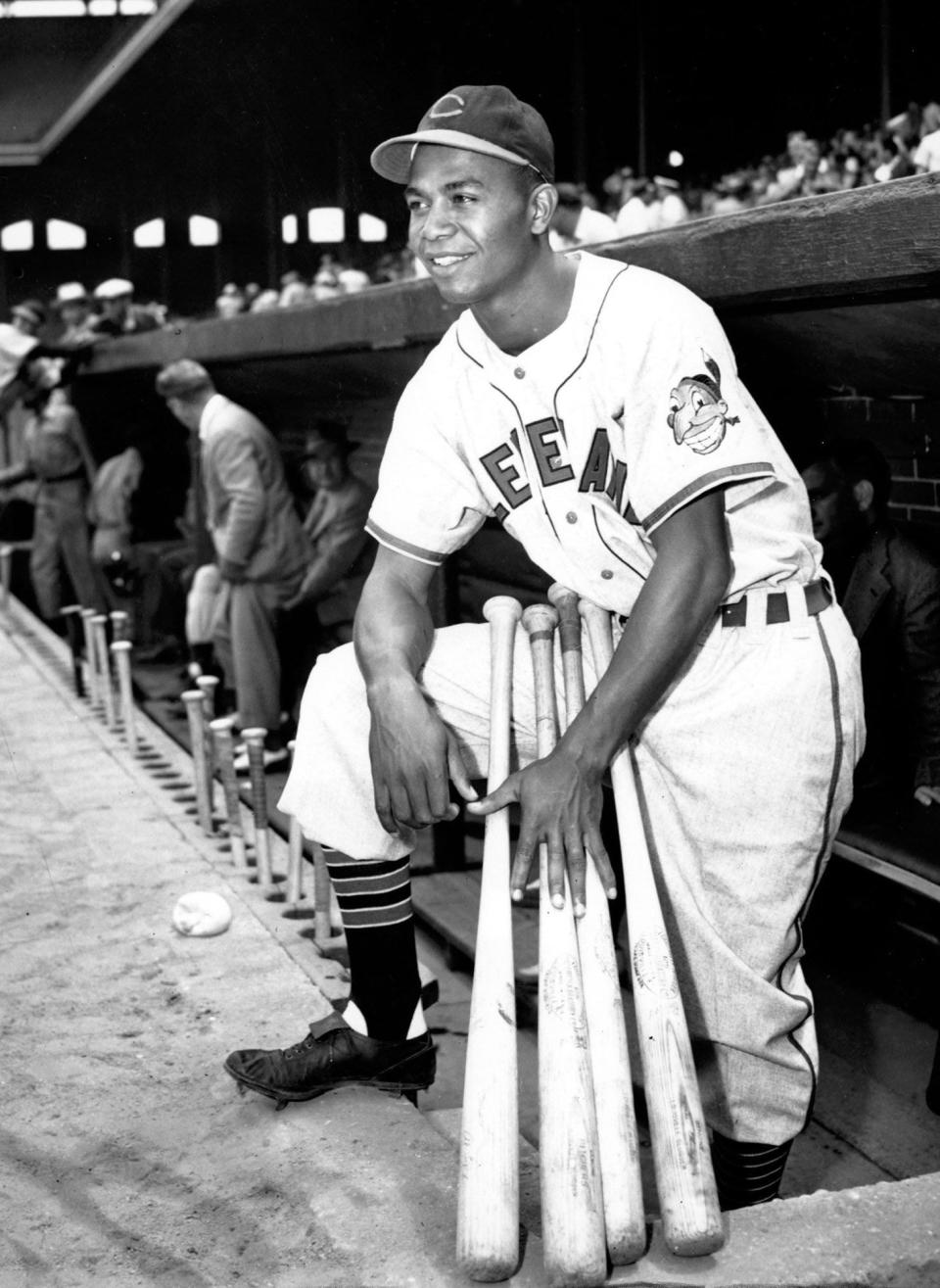

Larry Doby, who broke the color barrier in the American League by joining the Cleveland Indians on July 5, 1947, lived in Montclair from 1960 until his death in 2003. He and his wife, Helyn, raised their five children in a house on Nishuane Road that is still in the family. Son Larry Doby Jr. lives there along with granddaughter Nicole Frasier; daughter Susan Doby Robinson also lives in town and works at Northeast School.

Yet many in Montclair look blank when Doby's name is mentioned — despite the fact that the Brookdale rest stop on the Garden State Parkway was renamed for him last year and despite his accomplishments on the field. He carried the Cleveland Indians to two World Series championships and was a seven-time All-Star and the second Black manager in baseball.

His bravery as a pioneer in integrating baseball has often taken a back seat to that of Jackie Robinson, who joined the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League just 11 weeks before Doby went to Cleveland. Yet Doby's challenge was, in some ways, even more daunting. Unlike Robinson, who had played in the minors, Doby went directly from the Negro Leagues to Major League Baseball, and he had less attention and support while facing the same bigotry, including death threats, that Robinson endured.

Locally, Doby also has taken a back seat to Berra, though his roots here extend deeper. He attended Eastside High School in Paterson, where he was All-State in three sports, and then continued playing at the iconic Hinchliffe Stadium for the Newark Eagles of the Negro baseball league. He lived in the area throughout his career.

Doby’s wife, Helyn Curvy, had even deeper roots in North Jersey. She and her family were part of the Ramapo Mountains community known as the “Jackson Whites,” whose forebears included Native Americans, Black people, and British and German soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War, according to the Larry Doby biography “Pride against Prejudice,” by Joseph Thomas Moore.

The Curvys were one of the most “successful and cohesive” Black families in Paterson, according to Moore. At the time of her marriage, Helyn was the first Black person employed by Bell Telephone in Paterson and possibly the entire Bell System.

Local hero

Last year, Doby finally started getting his due on his home turf. In addition to the new rest stop, Larry Doby Day was held at Paterson’s Hinchliffe Stadium on July 5, 2022, the 75th anniversary of the day in 1947 when he first stepped up to bat in a Cleveland uniform.

Doby came to Paterson and Eastside High School at age 14 from South Carolina, finally joining his mother, who had come north to find work washing clothes after her husband died when Larry was 8. Larry spent most of his childhood in the care of his grandmother and aunt. He and Curvy met and started dating freshman year; they were married for 55 years.

He was a five-sport athlete at Eastside, but football, not baseball, was his favorite sport, said Larry Doby Jr., who works as a Broadway stagehand and whose acting resume includes a stint on "Sex and the City."

“My father would talk about how the whole town [of Paterson] shut down and there would be 10,000 fans at the football games against Passaic and Central,” said Larry Jr. “That was some of his fondest memories. I’d hear those stories till they were coming out my ears.”

After high school, Doby joined the Newark Eagles baseball team and was also the first Black man to play professional basketball in the ABL, a precursor to the NBA.

Doby and Curvy married in 1946 after he returned from three years serving in the Navy in World War II, and they rented an apartment on Paterson's Hamilton Avenue. In 1949, just three months after the Indians won the World Championship and Doby was celebrated with a parade in Paterson’s streets, the Dobys had to call on the mayor to help them buy a home on East 27th Street after brokers refused to sell to them.

Christina, Leslie, Larry Jr. and Kim were born in Paterson, but when their parents again experienced discriminatory tactics in their search for a larger home there, they looked elsewhere.

In 1960, they moved to a newly built home in "an integrated neighborhood in the more enlightened town of Montclair," according to Moore's biography of Doby. Their fifth child, Susan, was born in the Nishuane Road house.

Move to Montclair

Montclair was a good choice, said Larry Doby Jr., since three of his mother’s sisters lived in town and another in Verona; several of her other siblings lived in Paterson. Helyn Doby was one of 10 children, in contrast with her only-child husband.

“My mom and dad loved Montclair. It was a good move,” said Larry Jr. “We lived in a great neighborhood. You could just walk around the block to see family. My mom had her sisters here, and if your mother’s happy, your father’s happy. It was pretty neat. Montclair was an awesome town to grow up in.”

Larry Jr., the only son, played baseball and basketball and was friends with the children of MSU and Rutgers baseball legend Fred Hill, who lived on Cliff Street in Verona near his cousins.

Larry Jr. was in middle school when the town started busing white kids to South End schools, which was “culture shock,” he said. He’d gone to Nishuane for elementary school, which was mostly Black. But the magnet school system that evolved at that time was a “really good thing,” he said.

Attending an integrated high school meant “you grew up to have friends of every color and realized that you were all more alike than different,” he said. “I’d always wanted to go to Eastside, like my parents, but I’m glad I was able to grow up here.”

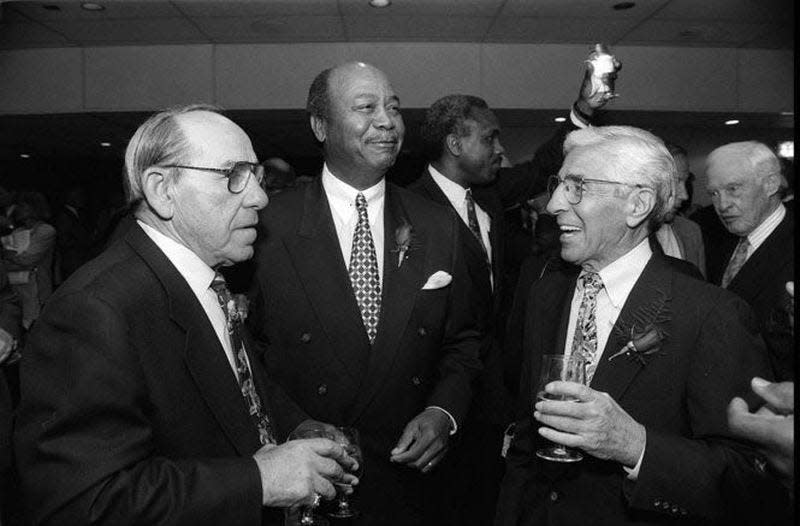

The Doby children were not allowed to throw their weight around because their father was a star baseball player. “There were a lot of rich and famous people in Montclair — Yogi was there, and Buzz [Aldrin], the second man on the moon. My father was a very quiet, understated, humble person, and he kept us grounded and humble,” Larry Jr. said. “You couldn’t say, ‘Do you know who my father is?’"

His father’s humility could be frustrating to young Larry, who would come up short when asking about his father's days in professional sports.

“Getting stories out of him was like pulling teeth,” he said. “I’d say, 'Tell me about playing Yankee Stadium, your home run,' and he’d say, ‘That’s history. I deal in today.’ You didn’t question him. I didn’t find out until he had passed away that he played pro basketball.

“The only time I heard him talking about baseball was when he was on the phone with reporters and I’d hide and listen. Or when he was talking to his friend Don Newcombe, who lived in Madison," Larry Jr. said. (Newcombe, a Black player with the Brooklyn Dodgers, was the first pitcher to win the Rookie of the Year, Most Valuable Player, and Cy Young awards during his career.)

“As I’ve gotten older I’ve formed this theory that his high school years were happier times, before racial prejudice was shoved in his face," Larry Jr. said. "Maybe the memories and stories about the big leagues were too painful to repeat and he shielded us from that.

"But I had to listen all the time to how Eastside had beaten Montclair when he was on the football team," he said with a laugh.

“It was a little frustrating, because there were so many questions I would have loved to have asked, but I respected who he was. He didn’t beat his chest and say, ‘I should have been in the Hall of Fame,’ nothing like that," the son said. "If they recognized him, he was happy; if they didn’t, he was fine with that, too."

Doby was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor posthumously in 2018.

“Strangely enough, my father’s life in Montclair was a pretty good illustration of his life in sports," Larry Jr. said. "You have this famous athlete, a former professional basketball player, a World-Series-champion barrier-breaker, living here. And he’s an afterthought to Yogi Berra, who also lives in town.

“There’s no jealousy or animosity; Yogi and my father were friends since 1947," Larry Jr. said. "Yogi’s legacy is also larger than life. But my father lived in a town where the Yankees rule. No one wanted to hear about the Indians.”

Larry Jr. said his father’s reluctance to talk about his time in Major League Baseball is not unlike the hesitation by members of the Greatest Generation to talk about their wartime service. He recalls his friend Dale Berra, Yogi’s son, telling him that the senior Berra never once talked about his experiences in the war.

“It was too painful," Larry Jr. said. "That was their duty. They did it but felt it was best not to talk about it. They wanted to get on with their lives.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Larry Doby broke barriers in MLB; left lasting legacy in Montclair

money

money