'How are you going to stop the internet?': Online child sex abuse explodes to crisis level

By the time Lex Smith reached puberty, her pedophile abusers had deemed her sexually worthless.

What started when a teenage boy sexually assaulted Smith when she was 8 or 9 years old during visits to her grandmother’s home in the suburbs of Chicago escalated to him recording himself raping her and selling Smith for sex, she said, to men “who wanted to kill me or wanted to harm me."

Smith escaped the harm around age 13, not because she was rescued in a sting operation or by shoe-leather law enforcement but by her own natural development.

“Because I had breasts, people were not interested anymore,” said Smith, 30, an advocate and consultant for victims of abuse and trafficking. “If there’s not a market to sell, they move on.”

The market for child sexual abuse material – or CSAM, the term preferred by law enforcement and advocates over child pornography – has exploded to crisis levels since Smith broke free of her abuse more than 15 years ago, according to law enforcement officials, advocates and survivors.

It's gotten worse in the COVID-19 pandemic: Reports of CSAM spiked 28% – from nearly 17 million in 2019 to 21.8 million in 2020, according to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Those reports do not include livestreams, the many millions of images circulating on the dark web or the unknown amount of material that isn’t reported by companies such as Apple – whose 265 reports in 2020 were among the lowest amounts flagged to the center that year.

One of Joe Biden's signature laws when he was a senator to investigate child abuse has never been fully funded by Congress, leaving law enforcement under-resourced and investigating a fraction of tips. In many cases, experts said, investigators prioritize cases based on the severity of abuse.

Now that he's president, Biden has the power and platform to bring the resources and attention to a problem that's become a global public safety threat that experts said demands a 9/11-style response to locate abusers and rescue children.

“If I were king for a day, I would set up an agency that is dedicated to this crime type because it’s so prolific," said Jim Cole, a Department of Homeland Security agent in Nashville. "I could take every agent in my office and dedicate it to this crime type and still be busy.

“It was a pandemic before we even used the word pandemic."

'We need help'

Biden and other lawmakers recognized the perils to children online before platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter became dominant sources of news and socialization.

The PROTECT Our Children Act of 2008, sponsored by Biden when he was a U.S. senator from Delaware, authorized Congress to spend $60 million a year to support the nation's 61 Internet Crimes Against Children task forces of local and regional law enforcement.

The closest Congress came to fully funding the task forces was when it used economic stimulus money in 2009. The most it's earmarked since then was $36 million in the 2019 fiscal year, according to the Justice Department.

The chasm between funding and reports of sexual abuse has widened over several years.

In 2014, more than a million reports of CSAM were sent for the first time to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. The task forces received $27 million that fiscal year.

Last year, the center took nearly 22 million reports of abusive images or videos, while the government allocated nearly $35 million to the task forces – about $320 per investigation.

The task forces, or ICACs, conducted 109,000 investigations last fiscal year, according to the Justice Department. That's less than 1% of abuse reports.

“All of the ICACs across the country are seeing a rise in referrals and investigations, and we’re not able to keep pace,” said Matthew Joy, director of the Department of Justice in Wisconsin, one of the few states that funds its task force to make up for the lack of federal support.

“It’s a resource issue,” Joy said, “and we need help.”

The federal money is typically used to train investigators and purchase equipment, but rarely do law enforcement agencies have full-time staff dedicated to child abuse investigations. The average law police department in the USA employs fewer than 10 sworn officers, according to the Justice Department.

That means a majority of the country does not have a cybercrimes unit, said Brad Russ, executive director of the National Criminal Justice Training Center in New Hampshire and a former task force commander at the program’s inception in 1998.

“This is a highly specialized area where you need people who not only get the training but are able to focus their time and attention” on it, and most departments "have three, four, five officers" on their entire staff.

In New Jersey, the most densely populated state, the state police have 13 people in their Internet Crimes Against Children task force, and the Division of Criminal Justice has six deputy attorneys general, two detectives and a sergeant specifically to handle CSAM investigations. They work with more than five dozen law enforcement agencies to conduct investigations and carry out sting operations.

A bipartisan group of lawmakers led by Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla., who was a top sponsor of the House’s version of the Biden bill, have written the past several years to leaders of the House Appropriations Committee requesting full funding of the task forces.

To no avail.

Wasserman-Schultz acknowledged that the law she and Biden sponsored has not been fully followed but said she was confident the Biden administration would address shortcomings, such as annually issuing a national strategy and requiring more transparency at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

"We certainly haven't done anywhere near enough, but the good news is we’ve seen a shift," she told the USA TODAY Network.

Why there is hope for change

Advocates and survivors see the Biden presidency as the best chance to harness the government’s resources against the threat to child safety.

Early indications are promising.

A bipartisan bill in Congress, known as the EARN IT Act, would open online platforms to civil lawsuits if they host CSAM and establish a national commission aimed at preventing the sexual exploitation of children online.

The Biden administration proposed adding $26 million to the Department of Justice budget to support the PROTECT Our Children Act of 2008, which funds the nation’s five dozen Internet Crimes Against Children task forces.

“There hasn’t been a president prior to President Biden who’s been in a position to better understand this issue because he wrote the bill and passed it,” said Camille Cooper, vice president of public policy at the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

Because of the extent of the problem, Cooper has pressed the Biden administration to name a czar whose chief responsibility would be to focus on matters of online abuse and work to combat it in coordination with other countries and technology companies.

“It’s time to raise this level to one of national and global priority and urgency, and really the only way to do that in a sustained way is to have someone there at the White House advising the president on a daily basis,” she said.

Reducing the vast amount of CSAM online and tracking down abusers is an incredibly complex proposition. Law enforcement officials said it requires heavy investments in time, money and technology – elements often in short supply or competing with other priorities.

Some victims of abuse harbor skepticism about how much can be done, given how far behind the country has fallen.

Dante, who said he was sexually assaulted by a trusted family friend, said the government has not done enough since the Biden bill became law, and “it’s just too scary” for the public to recognize the severity of the problem.

So many images of his abuse circulated online that he had enough notifications from law enforcement to “start a bonfire,” he said.

“The images and the videos – they’re never stopped,” said Dante, a man in his 30s living in the South whose identity is being protected by the USA TODAY Network. “I mean, how are you going to stop the internet?”

A spokeswoman for the Biden administration did not respond to several messages for comment about the program's underfunding.

Depths of depravity

A cottage industry of violent videos and images has cropped up as the widespread availability of technology – such as iPhones, encryption apps and livestreaming – all but give viewers and abusers free rein to indulge their fetishes with impunity.

There are message boards with instructions to avoid detection and websites devoted to children under the age of 5, according to the Department of Justice. There are niche categories of abuse labeled “hurtcore” and “pedomoms.” For about $15, someone can order child abuse live and on-demand, the department said.

If there are any doubts about the depth of depravity online and the importance of law enforcement investigations, the arrest of the so-called Dark Web Cannibal should dispel them, said Steven Grocki, chief of the child exploitation and obscenities section at the Justice Department.

In the far reaches of the internet in 2018, Alexander Nathan Barter posted his interest in “necrophilia and cannibalism” to “see how it feels to take a life,” according to law enforcement.

When an undercover agent offered whom he said was his 13-year-old daughter, Barter showed up in Joaquin, Texas, with a knife and a trash bag.

Police seized from Barter a cache of electronic devices containing grotesque images, including a prepubescent girl performing oral sex on a man.

Barter pleaded guilty to child exploitation and was sentenced to 40 years in federal prison last year.

“The old notion of child pornography offense is it’s men in their basements trading pictures of kids and that’s where it begins and ends,” Grocki said. “The reality is it’s a whole lot more dangerous and involved.”

Hunting for solutions

In the absence of federal action, private citizens have stepped in to fill the void.

Seeing that “technology was playing a role in extending the crime” but “had yet to play a significant part in its solution,” actors Ashton Kutcher and Demi Moore started the nonprofit Thorn to invest in technological innovations to combat online child sex abuse.

Thorn’s spotlight tool, which is used by some law enforcement agencies, has helped identify 17,092 child victims of human trafficking since 2016, according to the organization’s website.

The lack of federal funding for investigations played a large part in the founding of the nonprofit Operation Light Shine in Tennessee. Its founder, Matt Murphy, is an Army Green Beret whose sister was a victim of human trafficking and was killed in 2019.

In his grief, Murphy researched ways he could get involved to help victims and their families and learned how under-resourced and poorly funded law enforcement is on issues of human trafficking and child abuse investigations.

What he learned was “appalling,” he said, and it's hard for him to fathom how the country has not responded with the resources of war. When he and other Green Berets deploy to combat zones in the Middle East, “we’ve got the full might of the United States military behind us,” Murphy said. Law enforcement does “amazing work,” he said, but its resources are limited.

“To come home and see our own people being tortured and hunted and trafficked, and there not being a United States military-style effort behind stopping it? That is why I'm here,” he said.

Operation Shine Light raises money so law enforcement in middle Tennessee can pay the salaries of investigators, and it provides resources for victims of abuse and trafficking. Murphy plans to provide a building with office space, a digital forensics lab and equipment to assist investigators.

Another consequence of the funding deficit is the reach law enforcement has in its investigations. Except for sting operations in coordination with multiple agencies, most investigations are opened in response to tips passed on from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

The center deals with the open web and often relies on tech platforms to report suspected CSAM to it. With more money and more investigators, law enforcement could be more proactive by searching for locations hosting or exchanging the images.

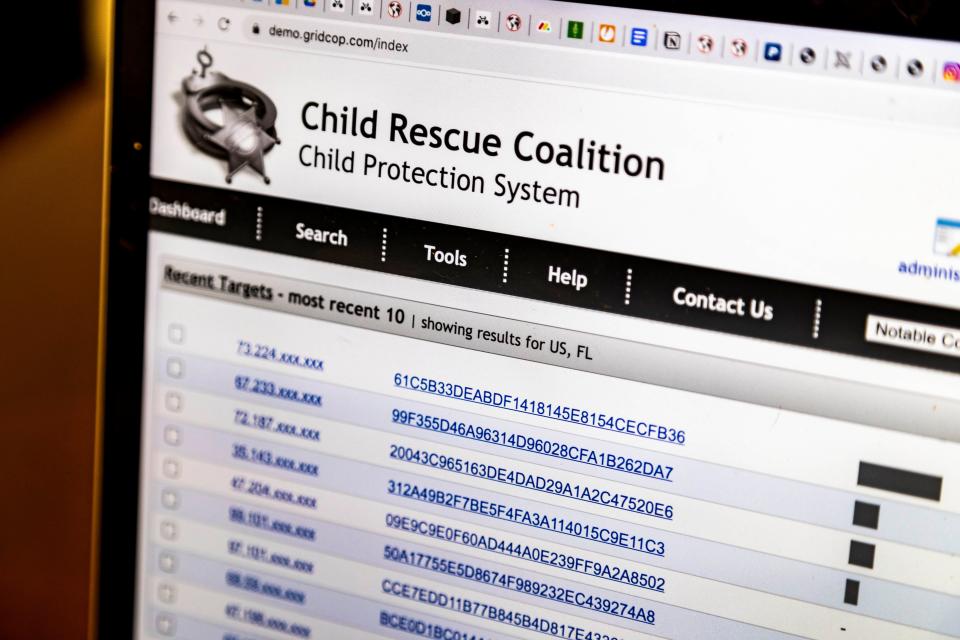

The Child Rescue Coalition, a Florida nonprofit that was formed out of a small team of law enforcement officers, developed technology that searches for networks hosting or trading CSAM. It gives investigators a real-time look, down to a user’s IP address, of illegal activity online.

Virtual tours of the technology offered a glimpse of its benefits to law enforcement. In April in New Jersey, the coalition’s screen showed 1,737 different unidentified individuals in possession and advertising abuse imagery of prepubescent children in the past 365 days. One person had more than 11,000 images.

Each day, the coalition collects and indexes 30 million to 50 million reports of online users trading CSAM, it said.

The coalition trains investigators around the globe for free, and more than 10,000 law enforcement officers use it, but many agencies do not because they lack funding and resources.

“If they’re already inundated with the national center tips, they will never get to our leads,” said William Wiltse, president of the coalition.

Experts and survivors of abuse agreed that the horrific nature of child sexual abuse makes it difficult to discuss publicly and it is easier to dismiss it as a problem that won't affect their lives.

People "should appreciate how rampant this is, how astronomical the numbers are," said Eleanor Gaetan, vice president of public policy at the National Center on Sexual Exploitation.

Lawmakers must act with more urgency, she said.

"What are our laws supposed to do? Deterrence, not eradication," she said. "Criminals will always be criminals. But we don’t even deter this stuff."

Reach reporter Dustin Racioppi via email (racioppi@northjersey.com) and Twitter (@dracioppi).

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Online child sex abuse at a crisis level: Can Biden help solve it?

money

money