Foul play or suicide? 30 years after a body was found in a pulp vat, questions linger in Green Bay

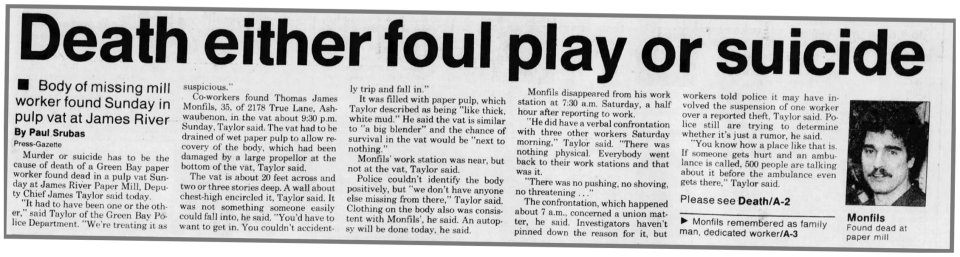

On a Sunday night in November 1992, employees at a Green Bay paper mill worked with police investigators to drain a massive vat of toxic pulp, where they made a horrific discovery.

There at the bottom was the James River Corp. employee they had been looking for since he went missing the previous day.

Tom Monfils, who was 35, failed to show up at his work station the morning of Nov. 21, and the search for him had taken nearly two full days. A supervisor ordered mill employees to drain the pulp vat around 8 p.m. Nov. 22 as it became evident Monfils had never left the mill. His car remained in the parking lot, his street clothes hung in his locker, and he never showed up at his home or other locations he frequented.

The vat was a two-story tank that contained a mud-like mixture of water, chemicals and paper pulp. Its large propellers at the bottom constantly stirred the mixture. Monfils' body was floating, anchored to the bottom of the vat with a jump rope around his neck tied to a 49-pound weight.

The tragic death of a mill worker was appalling enough to the Green Bay community. But soon, more troubling details surrounding Monfils' death emerged — including that he had made repeated phone calls over multiple days telling Green Bay police he feared for his life, desperate pleas that failed to protect him.

An autopsy determined Monfils was murdered. But more than two years passed before any arrests were made. In September 1995, six of Monfils' fellow paper mill workers — Keith Kutska, Mike Piaskowski, Michael Johnson, Michael Hirn, Dale Basten and Rey Moore — were convicted of first-degree intentional homicide as party to the crime after a joint trial and sentenced to life in prison.

Thirty years after Monfils' death, only Kutska remains in prison. The other five men have been released — one exonerated, the others on parole. One man has died.

To this day, all of the "Monfils Six" have maintained their innocence, and they've attracted a following of people who believe the men were wrongfully convicted. Two books have been published, claiming they were innocent. Among their defenders is Monfils' younger brother, Cal Monfils.

Their belief stems from a slew of developments over the last three decades, including a key witness' claims that he lied at the trial, allegations that the lead detective's aggressive investigative tactics led to false information presented as evidence, and family anecdotes that point to suicide as the possible true cause of Monfils' death.

A fatal mistake

The James River paper mill, as it was called in 1992, is located at 500 Day St. just north of downtown Green Bay, along the Fox River. It's a 121-year-old mill and — now owned by Georgia-Pacific — is in the process of being shut down for good. The mill has one working line of machines, which will cease operations next fall.

A drive past the property today will reveal vast, mostly empty parking lots. But in the early 1990s, the Day Street Mill was bustling with more than 1,000 workers running multiple paper machines from shift to shift. It supported generations of family members, many of whom worked alongside each other.

Workers at the mill were represented by two local branches of the United Paperworkers International Union: Local 327 and Local 213.

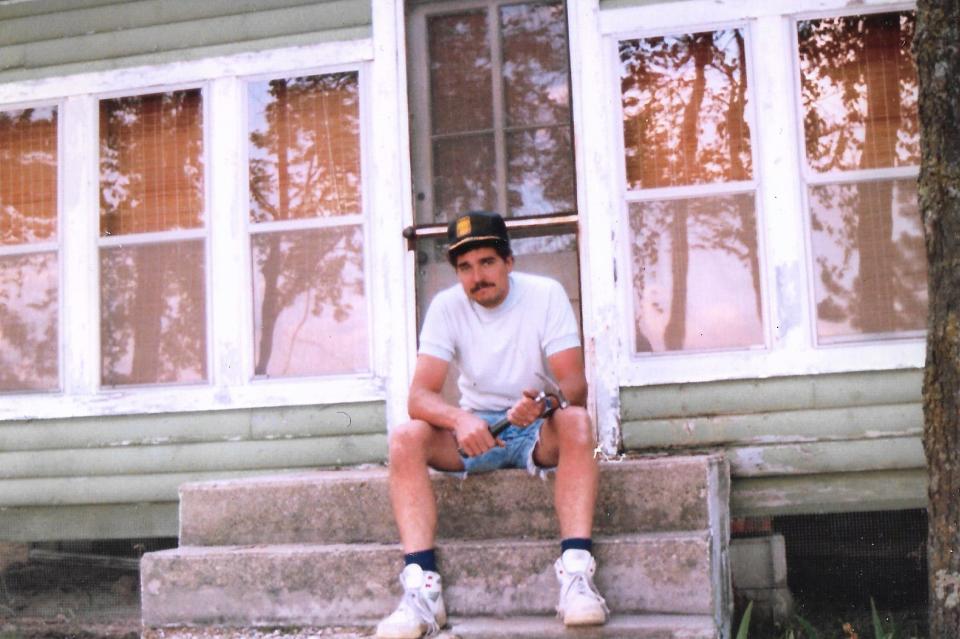

Monfils had worked at the mill since 1983. Before that, he served in the U.S. Coast Guard and worked a job in construction. His father, Ed, and uncle also worked at mill. Ed Monfils retired in January 1992, 10 months before his son's death.

Tom Monfils knew lots of people at the mill and was a bit of a "social butterfly," Cal Monfils, his younger brother, told the Green Bay Press-Gazette in an interview this month.

Cal Monfils no longer believes his brother was murdered, but prosecutors convinced a jury that some of those coworkers turned on him and took matters to a tragic end.

On Nov. 10, 1992, Kutska, who worked alongside Monfils for nearly a decade, took about 10 to 15 feet of electrical cable from the mill.

At 4:45 a.m. that day, Monfils called the Green Bay Police Department and reported that a theft was happening at the paper mill. He asked to be kept anonymous and expressed concern that Kutska was "known to be violent."

It wasn't abnormal for workers to take waste items from the mill, as long as they had an approved "scrap pass," Cal Monfils said. Likely, he said, his brother Tom was trying to get Kutska in trouble because there was a union vote approaching on the possibility of having 12-hour work days that would shorten the work week, and Kutska, a union representative, was expected to oppose the change.

Monfils call to the police to report the potential theft

The police department operator called the paper mill security guards to alert them about the potential theft. Because no officers were dispatched to the mill, the operator did not make a written report of the call. The call was, however, recorded per police department policy.

At the end of Kutska's shift, security at the James River mill stopped him on his way out the door and asked to search his bag. Kutska refused to allow it and was suspended from work for five days without pay.

Monfils called the police again two days later, on Nov. 12. He spoke with Detective Denise Servais, to whom he relayed the story and expressed fear of what might happen to him if Kutska found out he was the one who made the call. Monfils told the detective Kutska was "crazy and a biker type," and the detective reassured Monfils there was "no way in hell" the recording of his call would be released, according to court records.

Servais, however, made no written report of this call until after Monfils' body was found.

During his time off work, Kutska spoke with Marlyn Charles, president of United Paperworkers Local 327, the union representing Monfils, Kutska and other workers in the paper machine department, to discuss how Kutska could identify the informant and potentially file union charges against that person.

Kutska returned to work Nov. 17 after his unpaid suspension. That day, he called the police department and asked who had reported him to James River security. Lt. Michael Mason informed Kutska that he would need to know what time the phone call came in, and told Kutska he could call a different officer who might remember. Kutska learned of the time the phone call was made, and told a group of workers, including Monfils, that he was going to get ahold of the tape and find out who reported him to police.

That night, after 10 p.m., a frightened Monfils called the police department again and asked to speak to the "highest guy up." He was forwarded to acting shift commander Lt. Kenneth LaTour, and again relayed the story and said he feared Kutska would one day "take (him) out" and Monfils would not return home. LaTour said he was "not one hundred percent sure" the tape could not be released as public record, but told Monfils to call James Lampkin, who worked in the police department's communication department, to "put (his) fears to rest."

Monfils responded, "I definitely haven't got much sleep in the last couple of days."

LaTour did not refer the information from his call with Monfils to anyone in the police department and made no written report of the conversation, according to documents in a lawsuit the Monfils family filed against the police department. A U.S. Court of Appeals found the department negligent and awarded the family $2 million in 1997.

On Nov. 18, the day after he talked to LaTour, Monfils made a phone call to Lampkin, who told him the tape would not be released because it would have to cross Lampkin's desk first. Lampkin did not make a written record of this call until a week after Monfils' death.

On Nov. 19, Kutska called Mason, who located the recording and listened to it. Mason found no written report about Monfils' calls, because no one had at that point written any. Still uncertain whether he could release the tape to Kutska, Mason spoke with both an office worker and an assistant city attorney. From the recording itself, Mason did not hear any promise that the caller would be kept anonymous, and he did not know about the other calls Monfils made to the department. Although he was not the person at the department who typically releases records, Mason called Kutska that afternoon and said he could have a copy of the call if he brought in $5 and a blank cassette tape. At the mill, Kutska told workers he would be picking up the tape.

This seemed to further frighten Monfils. Around 10 a.m. Nov. 20, Monfils again called Lampkin, who told him the tape would not be released. Lampkin transferred the call to Deputy Chief of Detectives James Taylor, who also spoke to Monfils and assured him the tape would not be released.

But Taylor took no actions to ensure the tape did not get released. According to court documents, the tape was in fact sitting on a desk in the records office about 30 feet from Taylor, awaiting release, at the time he assured Monfils that Kutska would not get a hold of the recording.

The lawsuit against the police department and city of Green Bay was classified by courts as "Monfils v. Taylor," naming the detective individually. The suit was filed on behalf of Monfils' widow and two children.

Monfils also called the Brown County District Attorney's Office and spoke to Assistant District Attorney Pat Hitt, who believed there were grounds to refuse release of the tape under Wisconsin's open records law. Hitt called Taylor to tell him not to release the tape. Taylor replied that he knew about the situation. Hitt offered to also call Lampkin to ensure the tape did not get released, but Taylor assured Hitt it would not be released. Taylor checked the computer system only for reports of Monfils' Nov. 10 phone call. Finding no report he "just let it go," according to the Monfils v. Taylor decision.

Investigators would later say this was a mistake that cost Monfils his life.

That evening after work, Kutska obtained the tape and called Piaskowski, playing it for him over the phone. Kutska explained to Piaskowski that he had spoken to the union and that to file union charges against Monfils, Kutska needed two or three witnesses to identify Monfils' voice on the recording, since Monfils did not say his name in the call. Piaskowski agreed to be one of those witnesses.

On the morning of Nov. 21, Kutska showed up to work with a copy of the tape with Monfils' voice on it. Around 7 a.m., Kutska and another millworker, Randy LePak, entered "coop 7," paper machine No. 7's control room, where Piaskowski and Monfils were stationed. Kutska played the recording and asked Piaskowski to "name this tune."

Monfils, who was sitting in the corner of the room reading a newspaper at the time, admitted to Kutska that he had made the call.

Kutska played the tape for approximately 20 mill workers that morning, stirring up anger. Shortly after 7 a.m., he played the tape for a group that included Piaskowski, Hirn, Moore, Basten and Johnson at "coop 9," the control room for paper machine No. 9. Kutska implied Monfils' accusation of theft was false, and he told Moore and Hirn to "give Monfils some shit" for snitching on his fellow union member, according to court records.

Monfils left his post at coop 7 to perform a "turnover," which was a periodic task that involved taking a roll of paper off a machine and replacing it with a new one, scheduled for 7:34 a.m. Around this time, a confrontation allegedly took place at a water fountain between coops 7 and 9. The prosecution argued at trial that, during this confrontation, Monfils was attacked and left unconscious and severely injured.

Piaskowski declined to be interviewed for this story, but he told the Press-Gazette in a written statement that the "bubbler confrontation" theorized by investigators never occurred.

At 7:45 a.m., Kutska and Moore entered coop 7 and were followed shortly afterward by Piaskowski, according to court documents. Kutska told Piaskowski to alert a supervisor that Monfils was missing from his work station.

Piaskowski told a supervisor and said there was "some shit going down."

A search for Monfils ensued.

Sometime after 8 p.m. Nov. 22 — 36 hours later — workers found Monfils' body at the bottom of the pulp vat. The jump rope tied around his neck was attached to two PVC pipes, constructed by Monfils for exercise breaks during his workday.

His body was partially decomposed as a result of the chemicals and propeller in the vat.

Police initially considered both suicide and foul play as possible causes of Monfils' death. It wasn't until Dec. 9 that police announced at a news conference that Monfils had been murdered and a homicide investigation was under way.

An autopsy found Monfils had injuries that occurred before he went into the vat — that he had been beaten to the point of unconsciousness, then thrown into the pulp pit. His cause of death was ruled to be suffocation after ingesting paper pulp and strangulation from the rope around his neck.

The investigation began immediately. But no one was arrested until almost 2½ years later.

Investigation

That weekend was the start of deer hunting season. Cal Monfils had been up north hunting all weekend. He didn't find out his brother was missing until he returned home around 8 p.m. Nov. 22.

He received word of Tom's death hours later, in the early hours of the morning.

Tom was the third child of six kids born and raised in Green Bay. Cal, the youngest child in the family, was 25 years old when his brother died.

"Growing up, me and my brother were very close, even though he was 10 years older than me and he went off to the Coast Guard," Cal Monfils said. "But when he came back, we did a lot of things together."

Tom would buy and remodel rental properties, some of which Cal helped with. They also liked to water ski together. In interviews with the Green Bay Press-Gazette shortly after Tom's death, his family remembered him as a resourceful self-starter who loved to joke around. Tom also enjoyed roller skating — which was what he was doing when he met his wife, Susan, while stationed in New Jersey.

Monfils left behind his wife, an 11-year-old daughter, Theresa, and a 9-year-old son, John.

The investigation into Monfils' murder proved difficult. Police could find no blood stains, a murder weapon or concrete evidence that a struggle had taken place the day Monfils died. Instead, they had to rely heavily on interviews with people who were at the mill that day.

Investigators followed mill workers closely, monitoring movements and conducting interviews. Police parked outside their homes, dug through their trash and recorded phone conversations.

In December 1992, Kutska, Piaskowski and LePak were suspended from work without pay for about three months for their unauthorized meeting with Monfils the morning he went missing, according to Press-Gazette reporting from June 1995. James River fired Kutska in March 1993, while the other two men returned to work.

It wasn't unusual for James River to allow union members to take disputes into their own hands, managers for the company said during an April 1993 hearing to determine if Kutska, Piaskowski and LePak were entitled to unemployment benefits for their time off work. (The judge ruled they were not.) In June 1993, the Press-Gazette published that an executive assistant to the union's international president in Nashville, Tennessee, said the union encouraged its workers to report its problems to union leaders rather than company management — and that going directly to management causes "hard feelings."

James River's human resources manager released a statement that summer saying: "Not only do we have policies forbidding harassment or intimidation, we have been proactive over the years in helping our employees both understand and develop higher levels of awareness to such unacceptable behavior."

In a letter firing Kutska, James River Corp. Vice President Charles Warren wrote: "Organizing and engaging in such an intimidating, vindictive unauthorized confrontation with a fellow employee at work is intolerable and cannot be condoned."

As the investigation continued to unfold, members of the unions at the James River mill expressed frustration that police and the news media were making them look bad. In August 1993, the regional office of the United Paperworkers International Union issued a news release stating that the Green Bay Police Department and local media sensationalized "the misconception that union brothers standing together have hindered this investigation." Part of their concern came from reports from Detective Sgt. Randy Winkler that Charles, the president of United Paperworkers Local 327, lied to police about Kutska's theft.

In May 1993, Susan Monfils, with her attorney, Bruce Bachhuber, filed a lawsuit against Kutska, Piaskowski, Johnson, Hirn, Basten and Moore, as well as LePak, alleging that they were involved in intimidation and conspiracy that led to Tom Monfils' death. Action on the civil lawsuit stopped when the "Monfils Six" were criminally charged.

In August 1993, the James River Corp. offered a $25,000 reward for anyone who came forward with details about how Monfils was killed. The reward was increased to $35,000 that November, through contributions of businesses and individuals.

In January 1994, Winkler, who had been one of multiple investigators throughout, stepped in as lead investigator on the case, which had up to that point had few developments.

Kutska was the obvious main suspect from the beginning, given Monfils' fearful phone calls about him. But a group of men all had alibis for Kutska, that they had been with him that morning when he played the tape.

Winkler said he conducted more than 500 interviews. He and the other investigators came to the conclusion that the six men must have worked together to kill Monfils and hide the evidence.

Some of the biggest pieces of evidence for this theory hinged on testimonies from two millworkers: David Wiener and Brian Kellner, although each of those men became subjected to scrutiny about their credibility.

Six months after Monfils' death, Wiener contacted police after he recalled a memory from the morning Monfils went missing: Basten and Johnson walking toward a pulp vat connecting the No. 7 and No. 9 coops, about 6 feet apart, hunched over and seemingly carrying something between them.

Wiener said he remembered this "repressed memory" while at a wedding reception in May 1993, after hearing someone at the reception mention the name "Rodell." However, Wiener was one of about 12 people who testified at a secret John Doe hearing that March, and at that time said nothing about seeing Basten and Johnson.

Then, on Nov. 28, 1993, Wiener shot and killed his younger brother after an argument. He was charged and convicted of second-degree reckless homicide.

According to the Press-Gazette's coverage at the time, Wiener, then 31, was "under a great deal of personal stress" when he shot and killed his 28-year-old brother, Tim, at Wiener's home in Allouez. Wiener's coworkers said Wiener had taken time off work because of stress related to the Monfils case, although neither police nor James River confirmed if that was the case. Wiener's neighbors said police had his house under heavy surveillance following Monfils' death, and Wiener started using an unlisted phone number. And before settling their differences earlier in the fall of 1993, Wiener and his wife had filed for divorce and listed their house for sale.

Wiener told police Tim had been violent toward him in the past, and Wiener said he believed his brother was going beat him to death, according to court documents.

The other major piece of the puzzle for the prosecution's theory was testimony from Kellner, a good friend of Kutska who also worked at the mill.

After an hours-long interrogation by Winkler in November 1994, Kellner signed a statement saying that one night that summer, while he was out drinking with Kutska at the Fox Den Bar in the town of Morgan in Oconto County, Kutska drunkenly performed a reenactment of Monfils' beating, using the bar owners and others in attendance as actors. Kellner claimed he had consumed around 12 beers, while Kutska had drank close to 40.

The statement also mentioned that another time, Kutska accidentally dropped a tool on Kellner's head while they were working and made a joke about Kellner having a "Monfils lump." That was before the autopsy revealed Monfils had a wound on his head.

But as the 1995 trial approached, Kellner told Kutska's attorney that the police statement he signed was not entirely correct. He said Kutska had only tossed out theories about what might have happened to Monfils during the bar reenactment and the tool incident. Kellner also told the prosecution he was not comfortable with the entire police statement.

"His statement at that time was true to the best of his knowledge, I believe," Winkler told the Press-Gazette in an interview this month. "I'm sure after, (when) he was confronted by some of the suspects and other people that he worked with, yeah, he wanted to change the truth ... but, you know, it wasn't possible anymore."

On April 12, 1995, police arrested Kutska, Piaskowski, Johnson, Hirn, Basten and Moore — as well as LePak and Charles — at the paper mill. LePak and Charles did not face criminal charges.

The joint trial of the "Monfils Six" began Sept. 27 of that year.

Six defendants, one trial

After nearly three years of news related to Monfils' murder, the six defendants finally went to trial.

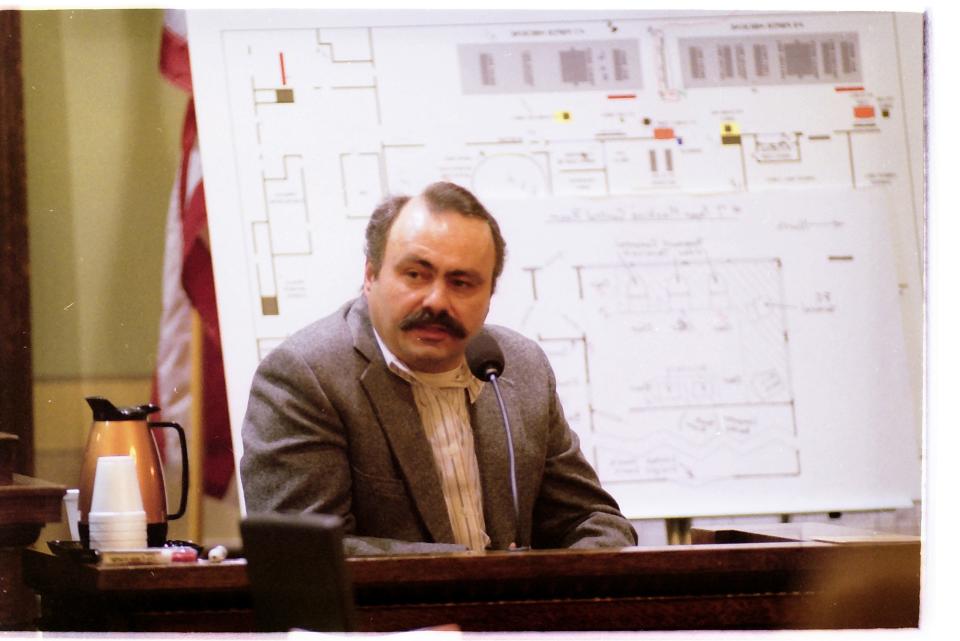

Leading the prosecution was Brown County District Attorney John Zakowski, with Assistant District Attorney Larry Lasee. The six defendants were each represented by one or two defense attorneys. Outagamie County Judge James Bayorgeon presided over the case.

Because of so much publicity surrounding the case, the Green Bay community carried strong opinions. To ensure impartiality, a jury was brought in from Racine County.

The entire trial lasted six weeks. The jury was sequestered in a Brown County hotel.

In the state's opening statements, Lasee told the jury: "If details are extremely important to you, you're going to be disappointed. There are gaps."

During three weeks of arguments, the prosecution painted a picture of an angry mob of union brothers who beat Monfils to unconsciousness and covered up that crime by tossing him to his death in the vat. But, as Lasee promised, the state lacked any single pieces of undoubtedly incriminating evidence. There was no physical evidence that a beating took place, no witnesses who saw the beating, no witnesses who saw any of the men appearing bloody or disheveled after the beating allegedly took place, and no one who saw a body — except possibly Wiener's recollection of what may have been a body, if his memory was accurate.

The state instead had to rely on testimonies from witnesses and the defendants themselves. Among testimonies the state presented as evidence:

Wiener testified about his recalled memory seeing Basten and Johnson carry something heavy between them that appeared to be Monfils' body around 7:30 a.m. the morning he went missing. Wiener also told the jury about his fear of Basten, and that he would not use the paper mill's restroom unless someone stood guard with a knife. When asked by Zakowski why Wiener had said nothing of his memory at the John Doe hearing in March 1993, Wiener said he "had a mental block or something."

Kellner testified about the Oconto County bar reenactment but stated Kutska's statements about attacking Monfils were hypothetical — how it may have happened.

James Gilliam, who shared a jail cell with Moore, testified that Moore said he beat Monfils but didn't kill him. Gilliam said Moore told him that during the confrontation, Kutska "popped" Monfils in the face, and Moore stood over Monfils "like everybody else" and punched at him. Gilliam testified that he asked Moore who killed Monfils, and Moore allegedly pointed to a newspaper with the six defendants on it and said "pick your choice." (In 2001, Gilliam was sentenced to life in prison for stabbing his wife to death).

James Charleson, an inmate who stayed in the same cell block as Dale Basten, testified hearing Basten make a telephone call allegedly saying he knew who killed Monfils and that he "should have left town when the police were questioning everyone."

A woman named Dodie Verstrate, who befriended Kutska when he helped her husband pour concrete in 1994, testified at a preliminary hearing that Kutska told her he had killed Monfils, and that the killers' only mistake was putting his body in the wrong vat — the correct vat would have destroyed his body.

Multiple millworkers testified to being afraid of Basten. One worker, Alan Kiley, wrote a letter to prosecutors asking them not to call him as a witness at the trial after Basten asked him not to tell anyone what they talked about in regard to the Monfils case. Kiley, who helped drain the pulp vat when Monfils' body was discovered, testified to seeing Basten in the area at least five times that day. Another, David Webster, testified that he felt worried at the mill because of Wiener's "paranoia" and Basten asking many questions, including what Wiener knew about the murder.

Another millworker, John Abts, told the jury that a month after Monfils died, he heard Johnson say, "Monfils got what he had coming."

When it came time for the defense arguments, each of the six men's lawyers argued that their clients were innocent and that someone else must have murdered Monfils. According to Press-Gazette trial coverage at the time:

Kutska argued that he had thought playing the tape for the other workers would lead them to ostracize Monfils, not cause any physical harm. He denied harming Monfils or knowing who did.

Hirn admitted to confronting Monfils about the tapes, but only verbally. He said Kutska had encouraged him to say something to Monfils, and he did because he "wanted to be one of the boys," Hirn said at trial. Hirn's attorney hinted that Kutska and Moore may have been involved in Monfils' disappearance.

Piaskowski claimed he reported Monfils missing from his work station shortly before 8 a.m. the day he disappeared not because he believed something had happened to Monfils, but because he wanted Monfils to get in trouble with management. His attorney hinted that Kutska, Moore and Hirn may have been responsible.

Moore's attorney argued that Moore did not know who Monfils was, and did not even arrive in the area until after Monfils had already been harmed. Part of a different union than the others, Moore was asking other workers to identify who Monfils was up until the point when the state believed Monfils was already dead. His attorney argued that people claiming they saw Moore in the area mistook him for a different Black employee.

Basten and Johnson suggested that the wrong people were on trial, and that the real killer may have been Wiener.

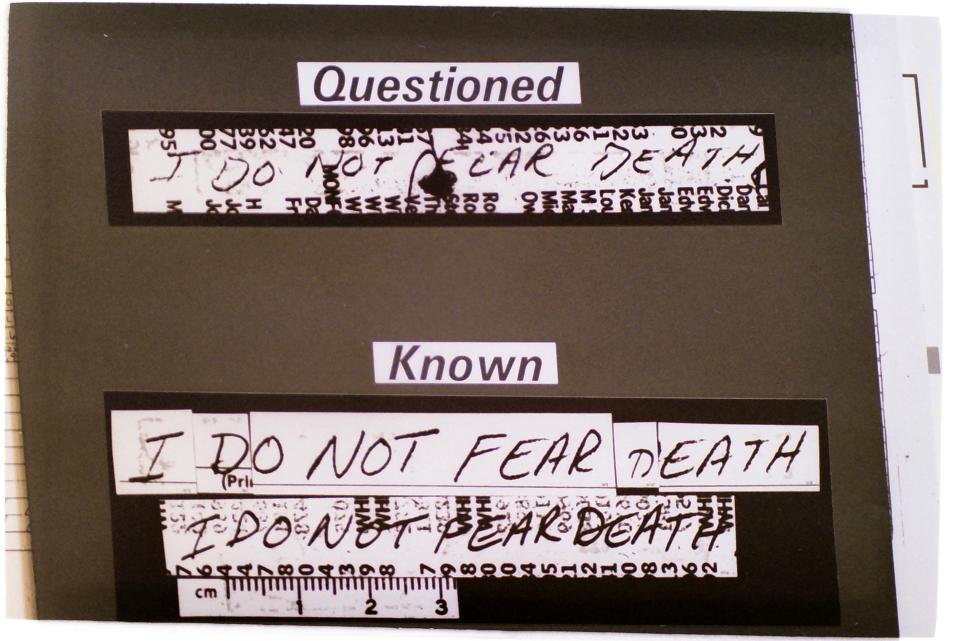

The theory that Wiener could have been the real killer was based on a few things: the fact that he had proven he was capable of killing someone when he murdered his own brother, the suspicious nature of his recalled memory, and a religious message that was found in a phone book that defense attorneys argued might have been a fake suicide note written by Wiener.

The note, written in pencil on the page of the phone book that contained Monfils' name and number, said "I do not fear death for in death we seek life eternal." Although Wiener said he did not write the message, two handwriting experts testified that the handwriting did not belong to Monfils and was likely Wiener's. Basten's attorney also argued that the heavy object Wiener claimed to see Basten and Johnson carry could not have been Monfils' body, because Wiener claimed to have seen them at 7:30 a.m., and Monfils was reportedly seen alive after that.

Basten's attorneys also brought in a psychology professor as an expert witness to testify about the reliability of memories, who said that memories can change when new information is brought in, and people can fill in gaps in their memories and be unable to distinguish what actually happened from something they "constructed." The professor testified that it's possible an interviewer's insisting that someone remembers something could cause that person to unconsciously create a false memory. Multiple witnesses testified that Winkler continued to aggressively question people after they already said they did not remember — and that some of those people ended up recalling events later, according to the Press-Gazette's coverage of the trial.

Defense lawyers also questioned if Wiener had ulterior motives for testifying, so he could get a reduction in his prison sentence. Both Wiener and the prosecution denied Wiener was offered any deal for testifying at the Monfils trial. However, his sentence was shortened from 10 years to eight years in May 1996, and that September, he was paroled after serving three years of his prison sentence.

Sgt. Allen VanHaute, one of the lead detectives on the case, told defense attorneys during questioning that there was likely no physical evidence because police did not know a crime had been committed until about 36 hours after it allegedly took place, and the mill was regularly sprayed down to clean pulp residue.

After hearing closing arguments, the jury's deliberation took just 10 hours. The verdicts were delivered around 6:25 p.m. Oct. 28, 1995. It was a Saturday evening. Monfils had been dead for nearly three years by then.

The front page of the Green Bay Press-Gazette the following morning said it all: "Guilty, guilty, guilty, guilty, guilty, guilty."

Aftermath and appeals

Community members had mixed responses upon hearing the verdict. The Press-Gazette reported multiple people's comparisons to the guilty verdicts in the Monfils trial, for which evidence was primarily circumstantial, to the not guilty verdict in O.J. Simpson's trial, for which significantly more physical evidence was presented. The O.J. Simpson verdict came out Oct. 3, 1995, in the midst of the Monfils trial.

To this day, none of the "Monfils Six" has confessed to killing Monfils or knowing anything about how he died.

The Press-Gazette tried to reach each of the five men convicted (Dale Basten, the sixth man, died in 2018). Piaskowski declined to be interviewed but provided a written statement and responded to emails. Hirn told a reporter he would consider an interview but later did not respond to follow-up calls. Johnson and Moore could not be reached. Kutska has not responded to a letter a reporter mailed to the Prairie Du Chien Correctional Institution seeking an interview.

Zakowski and Winkler, in interviews for this story, said they remain confident that the right men were brought to justice for Monfils' death.

"I think with time, that's only solidified the belief that the jury made the absolute right verdict, that they reached the only logical conclusion from the evidence," Zakowski, who is now a Brown County Circuit Court judge, told the Press-Gazette.

Cal Monfils said he feels the opposite.

“Every day that goes by, it makes less sense," he said. "I don't blame the jury. They heard some questionable evidence, and there's also things that they should have heard that they didn't hear."

In 1997, the same year Susan Monfils and her two kids were awarded $2 million in their lawsuit against the police, Detective Winkler was placed on leave for several months while the department conducted an internal investigation. He told the Press-Gazette that leaving the department was directly related to stress from the case, but he declined to elaborate. He retired in November 1998.

In 1997, at a post-conviction hearing requesting a new trial for Basten and Johnson, Kellner testified that he lied at the 1995 trial when he said Kutska told him Basten and Johnson were part of the group that confronted Monfils about the tapes. He also testified that all of Kutska's comments about Monfils' death were hypothetical and preceded by "what if" statements.

Kellner said he lied because Winkler had threatened he'd lose his job and custody of his children if he didn't provide what was needed.

All six men worked with their lawyers to file appeals.

After exhausting his appeals, Piaskowski petitioned the federal district court for a writ of habeas corpus, which is a request to be brought before a judge to challenge unlawful custody. U.S. District Court Judge Myron Gordon granted the writ and ruled that there had been insufficient evidence to convict Piaskowski. The state appealed that decision, and in July 2001, the district court's decision was upheld by the U.S. Seventh Court of Appeals — meaning Piaskowski was in effect acquitted, and unable to be tried again.

Connecting the evidence available to the conclusion that Piaskowski knew about and was involved in killing Monfils "requires a leap of logic that no reasonable jury should have been permitted to take," the Court of Appeals' decision read.

The decision also stated, "the record is devoid of any direct evidence that Piaskowski participated in the beating of Monfils, and the available circumstantial evidence at most casts suspicion on him. This is a far cry from guilt beyond a reasonable doubt."

After six years behind bars, Piaskowski was a free man. He walked out of the Dodge Correctional Institution to awaiting family members on April 3, 2001.

The other five men had reason to feel hopeful after hearing Piaskowski was exonerated. In a Press-Gazette article from July 2001, Basten's lawyer, Bob Byman, was quoted as saying Piaskowski's successful appeal was "good news for all of the other defendants," because it seemed to point to the possibility that if the state did not meet the "legal standard" to convict Piaskowski, the same might be true for the other men.

But the others remained in prison, despite attempts to get their convictions overturned or sentences reduced.

Each of the men was repeatedly denied parole for years. Hirn, Moore and Johnson were first eligible for parole in April 2010. Johnson was first eligible for parole in April 2011. Kutska was first eligible for parole in 2015.

Kutska, who had been unsuccessful filing a motion for postconviction relief in September 1997 and a habeas petition in April 2002, tried a new tactic in 2014.

In October 2014, Kutska filed an instant post-conviction motion. It resulted in multiple motion submissions and an evidentiary hearing.

While the original hearing and previous appeals took the defense argument that Monfils was killed by someone else, Kutska's new defense team at his 2015 evidentiary hearing argued that Monfils' death was a suicide, and the whole case had been built on an incorrect conclusion from the autopsy — that Monfils' injuries could not have occurred in the vat, and thus he had to have been beaten up and murdered.

Retired Minnesota lawyer Steven Kaplan, who worked with the Innocence Project in Minnesota, was instrumental in getting the evidentiary hearing for Kutska. Kutska's attorneys got a group of experts in the pathology department at the University of North Dakota's medical school to review the autopsy. They believed that the autopsy did not unequivocally show that the cause of death was homicide; it could have been suicide, with wounds to Monfils' body occurring from his body hitting the walls of the vat or getting hit by the vat's propeller-like blades.

Helen Young, the medical examiner who conducted Monfils' autopsy, died in 2007, eight years before the hearing.

The new hearing for Kutska also aimed to discredit Kellner's testimony from the 1995 trial. But Kellner died in 2014 before he could sign an affidavit swearing to recanting his testimony. However, days before his death, Kellner told one of Kutska's lawyers that the Fox Den Bar role-playing incident never occurred at all and that Kutska never discussed Monfils' death at all that evening, according to the motion for postconviction relief.

At the 2015 evidentiary hearing, Kutska's defense team had 14 witnesses testify, according to court records. Those witnesses included a forensic pathologist, Kutska's trial and appellate counsel, Winkler and multiple friends and family members of Kutska, Kellner and Monfils, including Cal Monfils. The hearing was overseen by Bayorgeon, who came out of retirement to revisit the case he presided over in 1995. Leading the prosecution was Brown County District Attorney David Lasee, whose father helped prosecute the original trial.

Kellner's daughter, Amanda Williams, testified that in 1994 and 1995, when she was around 13 years old, Winkler once interviewed her without her parents' permission or knowledge. Williams also testified that once at school, she was called to the principal's office, where a woman questioned her about her home life and the Monfils case. Williams said the woman then brought her to the Oconto Falls police station, where she was not questioned further, according to court documents.

Zakowski told the Press-Gazette he believes Kellner's original testimony was accurate, and he likely backtracked on his statements due to pressure.

"The way the original information came in from Mr. Kellner, it was very credible. I think he was a very credible witness. And then the subsequent appeals involved some walking back on that statement, but I think the courts realized the pressure that some of these witnesses were under," Zakowski said.

Winkler has denied making threats to Kellner. At the evidentiary hearing, he claimed he did not know Kellner had children.

Cal Monfils testified at the evidentiary hearing about evidence he heard through his family that Tom may have died by suicide. Cal Monfils told the court that Susan Monfils told his family shortly after Tom's death that she believed he had killed himself, and that Susan had found notes in their bedroom ceiling that seemed to indicate Tom's death was a suicide.

Further, Cal said, the knot that was used to tie the jump rope to the weight around Tom's neck was a type of nautical knot that Tom tied often.

In an interview with the Press-Gazette, Cal recalled going to Tom's house shortly after his death. There, in the screened porch, Cal found string tied to nails in the ceiling, as if Tom had been spray painting something and hung it up, then cut the ropes, leaving just the knots. Cal pulled the nails down and inspected the knots — they were the same knot found on the rope tied to the weight on Tom's neck.

"It wasn’t that uncommon, but it’s not a knot everybody’s going to tie. And then, if you look at the accuracy of the way it’s tied ... that’s the knot he always tied," Cal Monfils said in an interview. "I used to cut down trees with him, and we went boating ... that was one of his knots.”

Further, a fellow mill worker, Steven Stein, testified at the 2015 hearing that Monfils used to speak about recovering the bodies of people who died by drowning themselves during his four-year stint in the Coast Guard. Stein also said Kellner, a good friend of his, mentioned to Stein on five or six occasions that he had lied to police out of fear of losing his job or family.

But the state argued that there was no new argument, and the theory of suicide had already been brought up in court and dismissed by the jury. A trial court denied Kutska's motion in January 2016. Kutska filed an appeal that same month, which was also denied.

"It's ridiculous to think that that was a suicide," Zakowski told the Press-Gazette for this story. "There were too many injuries to too many different parts of his body, including injuries to his groin and to his neck, which were consistent with being attacked."

Winkler echoed similar thoughts.

"That is so ridiculous. If you just look at the evidence — the fact that he had a weight tied around his neck, he was dumped in the bottom of the vat. He was knocked unconscious before he went into the vat. It'd be an impossibility for him to commit suicide."

Cal Monfils said he believes his brother may have been dealing with undiagnosed mental health issues and was having marital problems at home at the time of his death. Further, Tom feared losing his job at the mill when people found out he had reported a problem outside of the union, Cal said.

"Work, that was kind of his life ... and that was never going to be the same, because he was always going to be the guy that got Kutska in trouble," Cal Monfils said. "Can you imagine what was going through his head at the time?”

Cal Monfils said he volunteered to testify at the evidentiary hearing and has been vocal in his beliefs not in any effort to "dishonor" his brother, but in hopes of simply uncovering the truth.

"The only reason I'm disclosing everything I know and everything I've heard through the years is in all fairness to everyone." Cal Monfils said. "The truth is the truth, and everything should be out on the table."

But Cal was disappointed with Kutska's evidentiary hearing. He said he felt that the court did not genuinely consider Kutska's defense team's arguments.

"All they seemed interested in was protecting their verdict," he said.

In September 2017, Basten was dying in prison. He was released on parole for health reasons and died the following June, at age 77.

Hirn was released from prison on parole in June 2018. Michael Johnson was released in June 2019, followed by Moore in July 2019. Kutska remains in prison, and has been repeatedly denied parole. He will be eligible again on May 1, when he is 72 years old.

Impacts

The Monfils case not only dominated news and conversations in Green Bay, but caught state and national attention and led to new legal policies.

In October 1993, the state Legislature passed the "Monfils Law," which tightened security for releasing records that may lead to a person being put in harm's way. And the federal court ruling from Monfils' family's lawsuit set a precedent that police may be forced to pay damages for endangering the life of an anonymous informer.

Nov. 10, 1992: Tom Monfils makes a call to the Green Bay Police Department to report that coworker Keith Kutska was planning to steal scrap electric wire from the mill. Kutska is then suspended from work for a week.

Nov. 10-20, 1992: Monfils makes three calls to police officers, including the deputy chief, pleading that his tip be kept anonymous. He also calls the Brown County District Attorney's Office.

Nov. 20, 1992: Kutska acquires a cassette tape of Monfils' police call reporting his theft.

Nov. 21, 1992: Kutska returns to work and confronts Monfils about calling the police. Kutska plays the recording for other employees, making them angry. At 7:45 a.m., Monfils is reported missing.

Nov. 22, 1992: Monfils is found dead at the bottom of a pulp vat at the James River paper mill in Green Bay. He had a 49-pound weight around his neck.

Oct. 19, 1993: Wisconsin passes the "Monfils Law," tightening security on records that could be dangerous to someone if released.

January 1994: Randy Winkler of the Green Bay Police Department becomes lead investigator on the case.

April 12, 1995: The "Monfils Six" – Keith Kutska, Mike Piaskowski, Michael Johnson, Michael Hirn, Dale Basten and Rey Moore – are arrested.

September-December 1995: The "Monfils Six" face trial together, a jury finds all six men guilty and each is sentenced to life in prison.

June 1997: Police are found negligent in Monfils' death, and his family is awarded more than $2 million in a lawsuit.

February 1998: The Wisconsin 3rd District Court of Appeals upholds Basten's, Johnson's and Moore's convictions.

June 1998: The Wisconsin 3rd District Court of Appeals upholds Hirn's conviction.

September 1998: The Wisconsin 3rd District Court of Appeals upholds Kutska's and Piaskowski's convictions.

April 3, 2001: Piaskowski is released from prison after U.S. District Court Judge Myron Gordon ruled there was insufficient evidence to convict him.

August 2009: The book "The Monfils Conspiracy: The Conviction of Six Innocent Men" is published. Authors Denis Gullickson and John Gaie had been working on the book for close to a decade.

January 2010: Judge Bayorgeon denies a motion for a new trial for Rey Moore.

Oct. 28, 2010: Family and friends of the "Monfils Six" hold the first annual "Walk for Truth and Justice" in Green Bay.

July 2015: Kutska appears for an evidentiary hearing, where he presents new evidence to argue he should get a new trial. After the hearing, he is denied a new trial.

June 12, 2016: An episode of "Deadline: Crime with Tamron Hall" about the case, titled "Alibis or Accomplices," airs on national television.

June 2017: The book "Reclaiming Lives: Pursuing Justice for Six Innocent Men" is published. Author Joan Treppa published a second edition with updates in June 2021.

September 2017: Basten is released from prison due to his failing health.

June 2018: Basten dies while living at a community care facility.

December 2018: Hirn is released from prison on parole.

June 2019: Johnson is released from prison on parole.

July 2019: Moore is released from prison on parole.

In 2009, two men, Denis Gullickson and John Gaie, published the book "The Monfils Conspiracy: The Conviction of Six Innocent Men," which argues that none of the "Monfils Six" killed Monfils. Gullickson is a Green Bay writer and Gaie is Piaskowski's former brother-in-law. In 2017, a Minnesota woman, Joan Treppa, wrote another book related to the case and advocating for the men's innocence, titled "Reclaiming Lives: Pursuing Justice for Six Innocent Men."

Zakowski said he read "The Monfils Conspiracy: The Conviction of Six Innocent Men." He calls it "historical fiction."

"Most of that was just a rehash of the arguments that the jury heard," Zakowski said. "There's no new evidence or revelation in anything that I've found, or anything that I've read since."

Winkler called the book "a big joke."

"Didn't even bother to waste my time with that," he said.

Treppa, Gullickson and Gaie declined requests to interview for this story, but encouraged reading of their books for their stance on the case.

The story has continued to capture people's attention. In 2016, the case was featured on an episode of the TV show "Deadline: Crime with Tamron Hall." The episode is titled "Alibis or Accomplices," and features interviews from a variety of people connected to the case. A documentary titled "Beyond Human Nature" was in the works for years but has not yet been released.

For years beginning in 2010, a crowd of people who advocate for the innocence of the "Monfils Six" held an annual "Walk for Truth and Justice" on the anniversary of when the six men were convicted. It was organized by the authors of the two books.

Thirty years later, Cal Monfils said his brother's death and conviction of six men afterward are on his mind often.

“There hasn’t been a day since it’s happened that I haven’t thought about it," he said.

In recent years, Cal Monfils has become close with Piaskowski and Hirn. They continue to help with efforts to prove the six men's innocence and try to get Kutska released to his family.

Family, friends and neighbors of the six convicted men began meeting up periodically around the end of 2009 and early 2010 to support each other and brainstorm ways to help prove the innocence of their loved ones. This group became known as the "Family and Friends of Six Innocent Men" or "FAF." The group's meetings continued until the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, Piaskowski said.

Cal Monfils said he attended multiple FAF meetings and got to know many of the six men's family members. He, along with others who attend the meetings, has written multiple letters in support of Kutska's parole over the years, each time Kutska becomes eligible again.

“I’ve written so many nice letters," Cal Monfils said. “I’ve been to Innocence Project things with his family and driven in the same vehicles. I said he has a great family waiting for him at home, which is where he should be.”

Cal Monfils said he questions why Kutska remains in prison for a crime that no one witnessed. Winkler said he believes other workers at the James River mill witnessed Monfils' murder but have remained silent for the last three decades.

“If there were 20 witnesses there that saw him shoot somebody 30 years ago, he’d be out. He’d be out. … And this was questionable and he’s still in," Cal Monfils said.

Statement from Mike Piaskowski

It’s well past the time of being misled by the results of the Monfils investigation and trial. Those results were both wrong. I/we did not kill Tom Monfils.

I have always been truthful; I do not know what happened to Tom.

What I do know is that we did not conspire to assault Tom or to end Tom’s life in any way. I also know that the Green Bay Police Department’s theory of a “bubbler confrontation” is wrong; that never happened. Whatever it was that happened to Tom, had to have happened to him somewhere else in some other way.

Their theory was based on circumstantial evidence, speculation, and hearsay; and it is completely wrong. The only thing that their theory achieved, besides causing six wrongful convictions, was getting the GBPD off the hotseat for failing Tom when Tom called them for help. (Just think about that for a minute)

For almost 30 years now the authorities have continued to claim that they got it right: But they didn’t. The reality is that they completely failed. They failed Tom, they failed Tom’s family, they failed the six of us and our families, and they failed their oath.

The former Brown County DA may have been right when he argued at trial that sometimes-circumstantial evidence can be stronger than their lack of any physical evidence of guilt. Ironically, using that logic, the last 30 years sounds a lot like circumstantial evidence of our innocence.

As a footnote: I would like to add how extremely grateful I am that we have a Federal Appellate Court system in place in order to correct the State’s failures. At least for me, that system worked and I got my life back. (Piaskowski v. Bett 256 F.3d 687 - 7th Circuit Court 2001)

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: The Tom Monfils case still cuts deep in Green Bay

money

money