As Florida braces for Hurricane Ian, a Fiona victim warns of storm surge 'coming with a vengeance'

Hurricane Ian’s forecast path northward near the Florida coast threatens millions, especially its potentially deadly and devastating storm surge that could push into bays and streams, flooding homes and businesses miles inland.

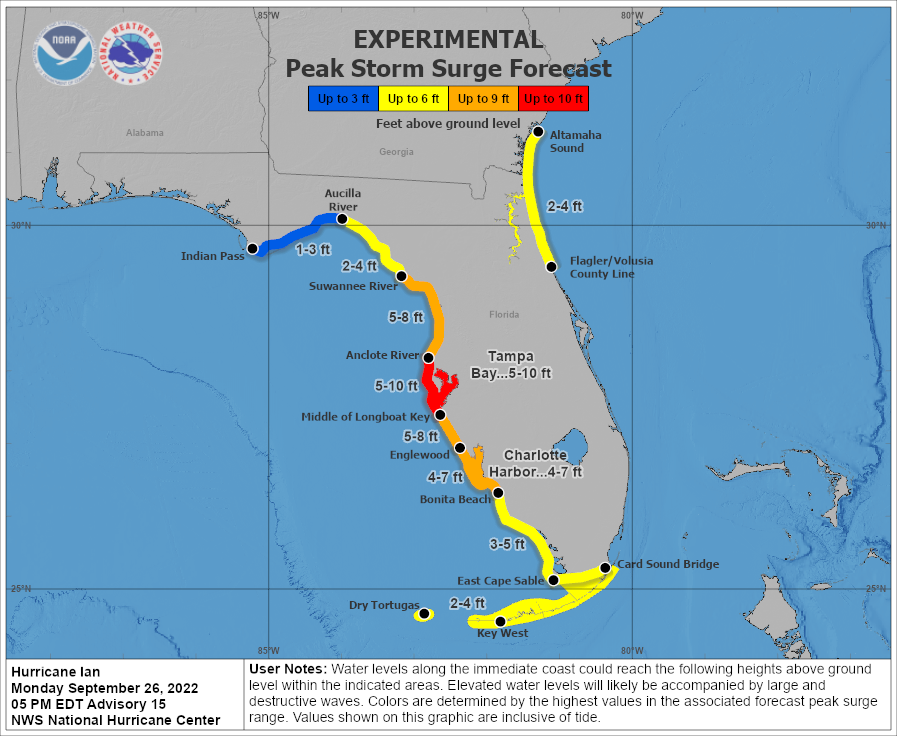

Uncertainty in the forecast Tuesday left much of the state's densely populated west coast facing the risk of a massive storm surge, from Naples north to the Big Bend.

A landfall in Tampa Bay is a nightmare weather scenario officials have feared for years for one of the nation’s largest and fastest-growing metropolitan areas.

"This would be the kind of life-threatening storm surge that would be kind of our worst-case scenario for the Tampa Bay area,” Keily Delerme, a National Weather Service meteorologist, told USA TODAY on Monday.

Far to the north, in Port Aux Basques, Newfoundland, on Monday, one woman who experienced Hurricane Fiona's storm surge firsthand, spent the day reflecting on her newfound respect for its dangers.

Videos over the weekend showed Fiona's surge ripping into the town and dragging homes into the sea, even after it was downgraded from a hurricane to a post-tropical cyclone. Storm surge claimed the life of one woman.

What is storm surge?: Explaining a hurricane's deadliest and most destructive threat

Hurricane categories, explained: How does the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind speed scale classify storms?

Jocelyn Gillam was standing in her yard talking to her brother-in-law when the initial surge arrived.

“I looked up and saw the water coming with a vengeance,” Gillam told USA TODAY. "It knocked me off my feet."

Muddied in shades of browns and beiges, the moving water pushed her under a Jeep, she said, where she quickly thought to grab onto a bar and hold on as water rushed over her.

The water held her under for what her brother-in-law estimated was two to four minutes before he and several men could pry up the vehicle and pull her out, ripping off her coat that was caught and holding her down, she said. "I’m lucky to be here.”

Storm surge – the rapid increase in water levels that push inland, topped by large and battering waves – has historically been one of the most deadly aspects of a hurricane, said Cody Fritz, a storm surge specialist with the National Hurricane Center. In recent years, extreme rainfall, fueled by climate change, claimed more lives.

Extreme rainfall: How a summer of extreme weather reveals a stunning shift in the way rain falls in America.

Risky living: Climate change makes living at the coast riskier. But more people keep coming.

Sea level rise, also driven by the warming climate, multiplies the hazards, especially along the north shore of the Gulf of Mexico, where the land is sinking as water levels are rising, federal officials said. Water temperatures in the Gulf are rising by about a third of a degree per decade, and warmer water expands.

“If you raise the sea level, it makes (storm surge) worse,” Fritz said. “Not only does it increase the depth of the water, it also increases the height of the water above ground.”

In Florida this week, storm surge and extreme rainfall are expected to ramp up the risks along more than 200 miles of the state’s west coast. Storm surge watches and warnings were in place along portions of both coasts Monday.

Rainfall could reach up to 24 inches wherever the center of Ian makes landfall later in the week, forecasters said. Up to 12 inches is forecast in other regions of central and north Florida.

Track the storm: Hurricane tracker: Where is Ian headed?

In any storm, the larger the storm, the more surge it can produce, former National Hurricane Center director Ken Graham, now head of the National Weather Service, told USA TODAY in April. A slower storm approaching an enclosed bay can also send the storm surge higher.

Ian was forecast to slow off the coast of Florida, and its wind field could expand. That sent storm surge estimates soaring to up to 12 feet, depending on the area.

The weather service warned “large areas of deep inundation are possible, accentuated by battering waves. Structural damage to buildings with several washing away.”

Storm surge from a major landfalling hurricane has been a serious concern for the Tampa Bay region for decades. The region is relatively flat, and a satellite view shows a wide shallow shelf offshore that stretches far west into the Gulf and allows water to pile up with a storm surge.

"The geological makeup of Tampa Bay makes it extremely vulnerable to flooding," said Matthew Eby, founder and chief executive of First Street Foundation. The nonprofit has launched a series of products to help the average homeowner understand their increasing risks from natural disasters supercharged by climate change.

"Even small amounts of sea level rise have an exponential increase on the risks to properties in that region," Eby said.

The depth of Ian's surge and the distance it pushes inland into rivers and streams will depend on how close the storm gets to shore, whether it arrives at high tide and how much rain falls, Delerme said.

"It’s very important that people know what evacuation zone they are in," she said. That's true whether you're inland or at the beach. Many rivers are at flood stage or just below and could rise rapidly as a result of the surge and rain. Much uncertainty remained with the Ian forecast Monday, and when it comes to storm surge, wobbles matter.

For example, a shift 15 miles to the west in Hurricane Laura’s landfall on the coast of Louisiana in 2020 would have significantly increased the storm surge in the town of Lake Charles, Fritz said.

Because the power of moving water in a storm surge is often underestimated, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has worked for more than a decade to raise awareness of the hazards, launching new graphics to try to help get the point across.

The agency has “made great strides in developing graphics that communicate the power and danger of the increase in water levels that occurs when a storm surge pushes water higher,” Fritz said. The hurricane center highlights three of those on its page for Hurricane Ian.

The new experimental peak storm surge graphics uses bold, bright colors to get its message across, and the inundation graphic shows the surge in height above ground level, Fritz said.

People can see their vulnerability right away, he said. It's all part of an effort to detach storm surge estimates from the wind speeds because they don't always match.

Weather officials also hope to correct the misconception that storm surge is not just a coastal issue, he said. “The hazard is much farther inland sometimes than people realize.”

Before she was released from the hospital after a night of observation, Gillam, in Canada, said the doctor told her she arrived with a face full of seaweed. “I didn’t care how I looked,” she said. She was happy to be able to go home and relieved that her family’s home and the homes of her neighbors survived.

Gillam didn’t understand the risks of storm surge before, but has now learned her lesson after a few minutes under the roiling cold and salty water, she said. “When they say there’s a storm coming, stay in the house.”

Dinah Voyles Pulver covers climate and environment issues for USA TODAY. She can be reached at dpulver@gannett.com or at @dinahvp on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Hurricane Ian storm surge may reach 10-feet, swamp parts of Tampa Bay

money

money