First gen students are missing from the nation's top colleges. Here's how virtual advising could help.

Lisbette Acosta thought Yale was out of reach.

Now a junior at the Ivy League institution in Connecticut, she wasn’t sure if it was worth her effort to apply to a place that rejects most applicants. She spent her free time caring for her two younger siblings in high school, one that didn’t offer clubs like Model United Nations. She didn’t have the time to start a nonprofit, travel the world or engage in other activities well-off students might pursue to pad their college applications.

Her counselors encouraged her to aim for a state institution in Connecticut, and Acosta was prepared to attend one.

Applying for college? What admission officers, Common App CEO say not to worry about

Then she talked with a Yale sophomore about what life was like at the university and the variety of students who called it home.

“I found that there was so much value in having someone who had the lived experience of being in college,” said Acosta, then 17. “It really gave me a good sense of like, ‘Do I see myself in this environment? Is it too much for me?’”

How likely are first-generation students to attend selective colleges?

That sophomore worked for Matriculate, a college advising group seeking to help high-achieving students from low- to middle-income families attend the nation’s top colleges. The group pairs high schoolers from these backgrounds with mentors at elite schools.

The service is free, too, though students have to apply and it's limited to families making less than $80,000 annually. Matriculate, which launched in 2014, is one of many organizations working to address a stubborn problem in American education: helping students from nontraditional backgrounds obtain a higher education.

Fraught and costly: More Latino students aim for a degree, but they face hurdles

Students from low-income backgrounds or whose parents didn’t attend college are less likely to pursue higher education themselves. When first-generation students do enroll, they typically attend open-access institutions at higher rates than their peers. These institutions, which include community colleges, tend to have lower graduation rates than more selective colleges but serve students who may need more academic support. They also generally have less money to provide for student aid and support.

What about high school college counselors?

Students’ access to college advising varies widely depending on the high school they attend. Private schools and public institutions in wealthier districts are far more likely to have robust college counseling services. A review of federal data for the 2021-22 academic year by the American School Counselor Association found that the average ratio of school counselors to students is 408 students to one adviser.

What happened to Biden's free college plan: Cutting cost of higher ed out of feds' reach

What is peer-to-peer advising?

Many independent college consulting companies rely on young people at or recent graduates of selective institutions for advice and support for high schoolers looking to attend these institutions. However, these services can cost thousands of dollars, usually a barrier for low-income students.

Some groups provide free or discounted services to low-income students, but many high school students are left to navigate the college application process with just their families or entirely on their own.

Making millions on international students: This Harvard grad's business is U.S. college admissions

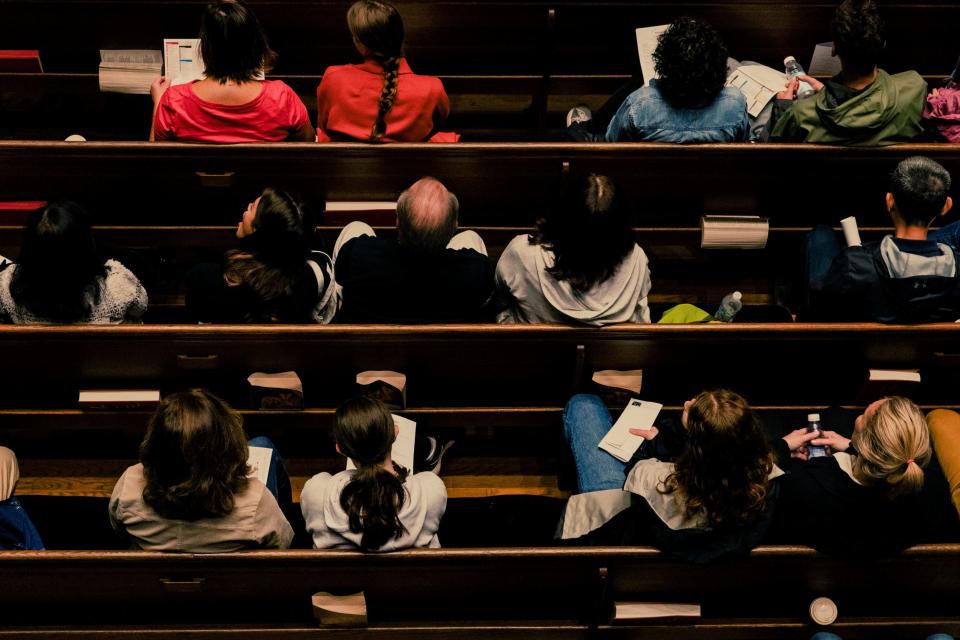

Students generally find Matriculate through word-of-mouth, social media and partner groups including the College Board. The organization pairs college students with high schoolers across the country, and they connect virtually to discuss which colleges they might want to attend or crafting a college application essay.

The company will receive about $15 million over the next three years from Bloomberg Philanthropies and investment firm Citadel and Citadel Securities. Matriculate already works with thousands of students and hopes to reach 10,000 students per class by 2030.

“We look forward to empowering students through virtual, near-peer advising, and in doing so, increasing access and equity in higher education,” said Madeleine Kerner, the CEO of Matriculate.

Does peer-to-peer advising work?

Ben Castleman, a professor of education at the University of Virginia, studies college access and the barriers students face in obtaining a higher education. In a recent paper, he and his coauthors found high schoolers who receive Matriculate's virtual advising are about 25 percent more likely to attend one of the nation’s top colleges than those who didn’t receive any support.

Lifechanging investment: How volunteer counselors can help guide more students to college

It’s the human element that proves most helpful, in contrast to once popular approaches to guiding students via text messages or similar digital reminders. This method, known in college-access circles as nudges, are popular because they’re cheap and easy to set up. However, Castleman said there’s little evidence they’re effective.

“Affluent families are not paying for a text messaging service,” he said. “They’re paying tens of thousands of dollars for someone who is going to meet with their kid every week.”

Can every student go to a top college?

Matriculate focuses on helping high-achieving students, those with a 3.5 GPA or higher, attend colleges that match them academically rather than less-selective institutions.

These colleges do tend to have higher graduation rates, higher returns on investment and greater financial aid for the neediest students. Attending one may grant students access to a robust social network. And most college degrees, regardless of the institution, are associated with higher earnings over an individual’s lifetime.

Ticket to ride: Princeton to offer full rides to students whose families make less than $100K a year

But there’s a limit on how many students the nation’s elite colleges can serve, which means some will inevitably be left out. At Yale, for example, about 20% of students qualify for the Pell Grant, a federal award geared toward low-income students. At nearby Gateway Community College, that share is roughly 65%.

Castleman said Matriculate's model could be replicated. High schools could connect students with recent graduates via Zoom calls or in-person meetups. Colleges could invest in programs to pair current students with applicants from underrepresented backgrounds. And families and high schoolers could seek out college students at institutions they’re curious about.

Students interviewed by USA TODAY for this story were advised by Matriculate advisers and now work as advisers themselves.

They’re unequivocal about the benefits.

Acosta, now 20, found the experience life-changing, so much so the junior became an adviser herself in the hope of making “higher education more accessible for students like me.”

Contact Chris Quintana at (202) 308-9021 or cquintana@usatoday.com. Follow him on Twitter at @CQuintanadc

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How virtual advisors offer college admissions assistance to peers

money

money