'Forgot you were there': Film projectionists are being lost in the digital age

“My dad used to say we could do time on a murder rap because it was just like a jail cell,” Joe Rivierzo, a third-generation projectionist, told Yahoo Finance (video above).

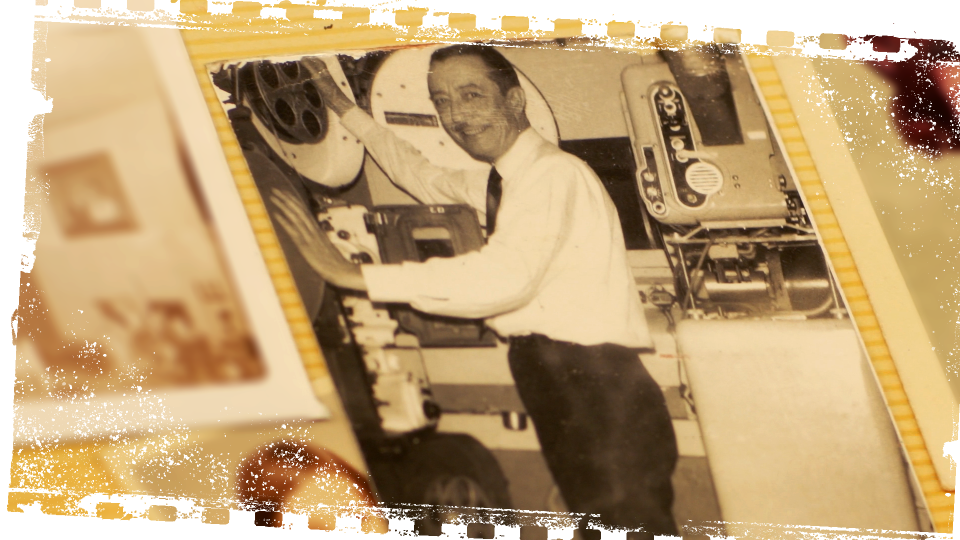

Rivierzo spent his earlier days putting movies on the big screen. He and his fellow film projectionists made sure the actual film material ran smoothly in the tiny room stuck behind the plush, red seats filled with popcorn-eating cinema-fans.

“If everything ran well, you didn't have to come downstairs for anything,” he added.

Once Rivierzo was even forgotten in the projection booth when the entire theater cleared out due to a bomb scare.

“You had to be a certain type,” says Rivierzo, referring to the solitary nature of the profession. “We were the last guy to touch the film after all that talent was assembled, right? Light guys, sound guys, actors, screenwriters… so I could ruin a blockbuster or a classic.”

‘My grandfather cranked all day’

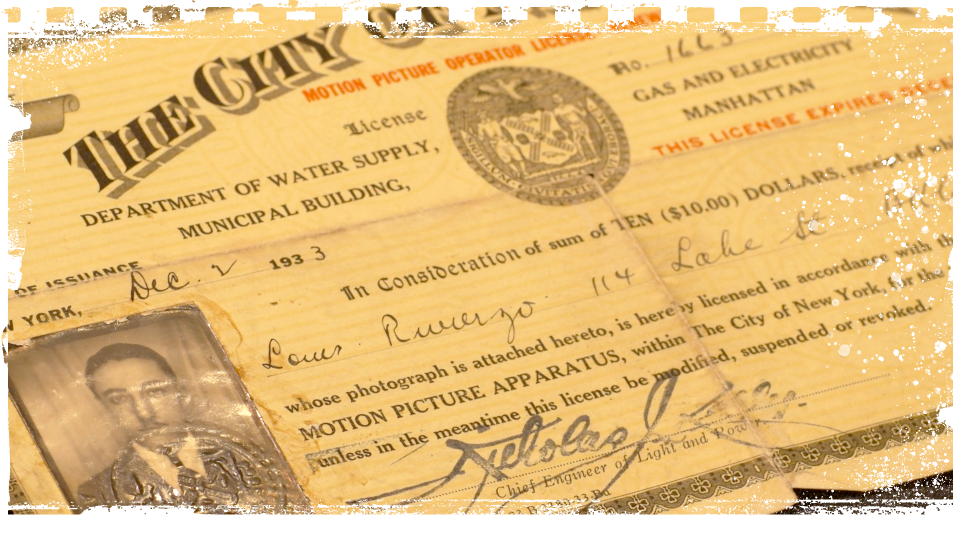

Rivierzo — who learned film from his father, Lou, who also learned from his father, Dominick, before him — saw cinema grow up in front of his pilot-glasses covered eyes. An Italian immigrant, Rivierzo’s grandfather operated a projector — with piano accompaniment because sound for film hadn’t been invented yet — in a Vaudeville theater in New York.

“The piano players changed twice a day, and my grandfather cranked all day. Even though they were synchronous gears, he would be slower than the fresh piano player. So my dad would bring my grandfather's dinner and crank the balance of the night after school,” Rivierzo said.

And so Rivierzo knows the history of the film projector operator and experienced the art form as his career developed. Now, after more than three decades, he has witnessed the fall of the film projector and the projectionist with the rise of digital media.

“The transition to digital. That's where my career in the projection booth pretty much came to an end — 37 years,” says Rivierzo. “Somebody's up in that booth right now. It's a lot of younger guys working computers and you know set up a whole week's worth of movies, but they're not union.”

Experts aren’t surprised by what’s happening.

“Art forms come and go, and styles of art forms come and go,” Richard Peña, professor of film studies at Columbia University, told Yahoo Finance. Peña also served as the director of the New York Film Festival from 1988 to 2012, and saw first hand the digital revolution in cinema. “I sometimes use the example with my students of something like the Blues. I lived in Chicago for eight years and I was always a great fan of Blues and became a bigger one when I was there. I mean, does anyone really think the Blues is still really a living form?”

He added: “All the forces of history are sort of in the digital direction and I don't think it's going to go back.”

‘He was fast, man.’

To become a licensed projectionist, New York required passing a test that had both a written and practical components. After passing the exam on the first try, Rivierzo recalled his father’s enthusiastic reaction: “You’d think I got into Harvard.”

Rivierzo’s father worked in screening rooms for dailies — footage shot in the morning that was shown later that night — and speed was the key. In addition to speed threading a projector, the job also required individuals to be mechanically inclined to triage inevitable malfunctions.

“He was fast, man. His fingers would fly through those heads,” Rivierzo recalled of his father’s adeptness. “Best projectionist I ever knew, and not because he was my father. But because he could fix anything given enough time.”

Rivierzo’s grandfather was a charter member of the Local 306 and his father was also a member. “He followed what his dad did, and that was fairly common even as I joined up in the '80s,” he explained. “You know you followed what your dad did.”

Rivierzo estimated a wage somewhere between $25 and $33 an hour for a projectionist in the union.

“A guy made a living,” he said. “He could afford a Buick and a house and put kids through college. He wasn't making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.”

Rivierzo’s union credentials speak for themselves: He is the longest continuously serving executive board member of the Local 306, Delegate to the IATSE 10th District, and Delegate to the New York City Central Labor Council. In its heyday membership in the Local 306 — which covered New York City’s five boroughs — was 3,500 strong. Today, that number has dwindled to around 150 operators in the union, and most of those have branched out to A/V production to make ends meet.

“It's certainly a very niche market, to just show film. But it comes down to the content, it comes down to are these films that people want to see?" Jesse LoCascio, a 28 year-old projectionist at the Jacob Burns Film Center in Westchester, NY, told Yahoo Finance. “I do think that there's still a place for projectionists. I still think that even in 2019, after the death of celluloid as people like to say, it's not dead. People still can do this for a living successfully.”

LoCascio, who also moonlights as a cameraman for digital film productions, is of a different generation and mindset.

“I think projection can still be a full-time career. I mean, the industry though for projectionists is certainly changing far as doing this for a living. I currently divvy it up between projection and film production, but I do know plenty of people that do this for a living full-time and do very well at it, and take it very seriously.”

In 2017, The Bureau of Labor Statistics put the number of projectionists at abound 5,700, and that number very likely includes individuals like LoCascio who have additional sources of income.

“What did I enjoy about it the most? I used to get a kick out of the kids,” Rivierzo said. “When the good guy would win, and you could hear ... that place would roar. You didn't even have to look up. You could just tell what part of the movie they were in.”

WATCH MORE:

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn,YouTube, and reddit.

money

money