The Real Story of the Birth of Fall Out Boy

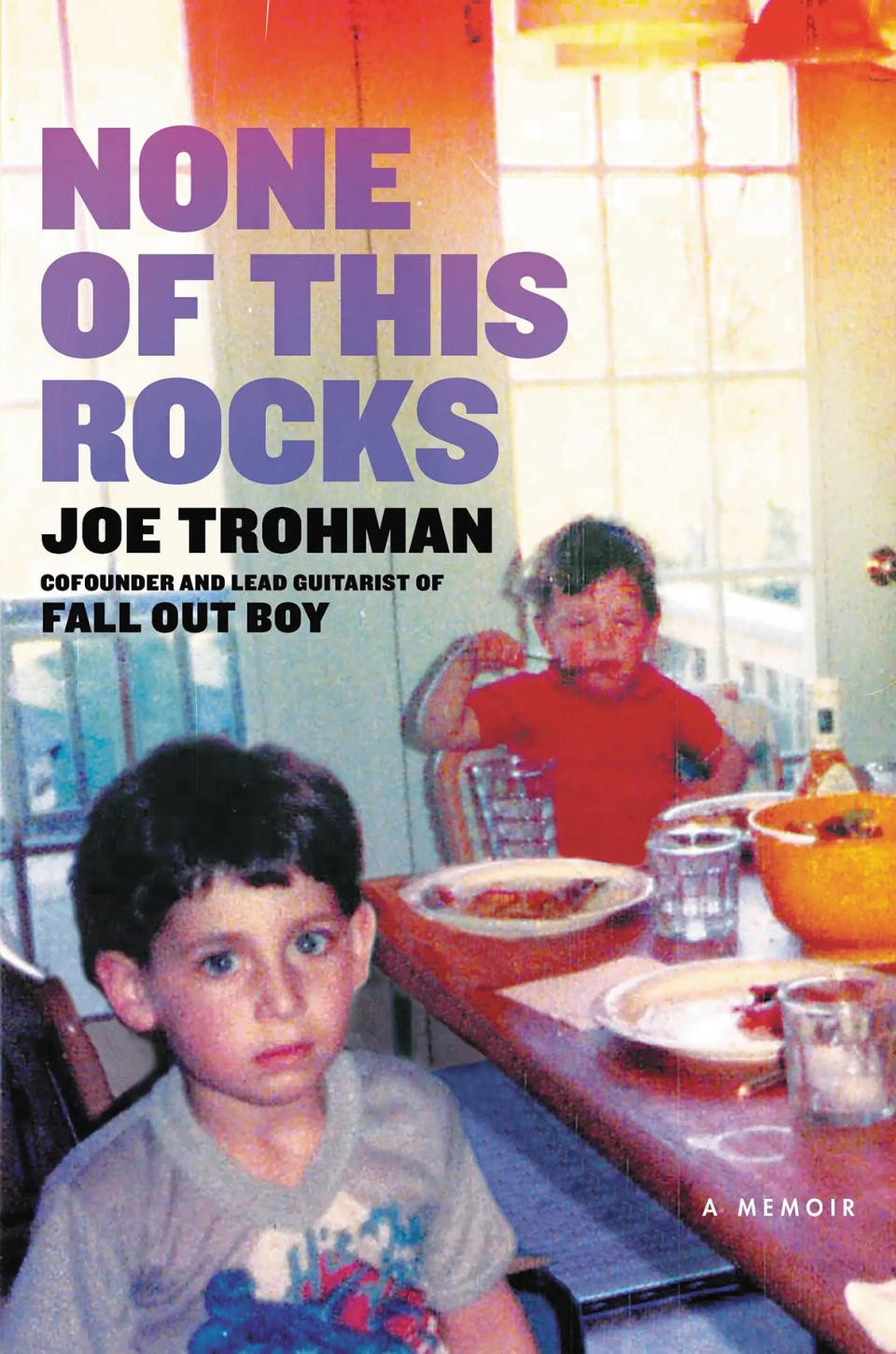

Joe Trohman’s new memoir, None of This Rocks: A Memoir, is a funny, sometimes dark, ultra-honest confessional from Fall Out Boy’s co-founder and lead guitarist. In this excerpt, he gives a detailed account of the formation of his band.

Many people know the story, so I think it’s wise that I tell it with brevity. Pete Wentz and I wanted to start a pop-punk band. Not only were we fans of the genre, but that particular music scene seemed to be budding in its own revitalized fashion, eventually turning into what would be known as the swoop-haired, eyeliner-clad, sad-boy emo movement of the aughts. But until that moment crescendoed, Pete and I only had ourselves, with me making it clear I was the guitarist since it was my formative instrument and him taking the role of bassist since he had performed as such in many local hardcore bands prior. All that was stopping us now was the lack of a drummer and some songs. Oh, and a singer. Neither of us could do that, the sing thing. That’s the hardest part, you know, of starting a band: finding a decent singer. If you don’t have that, you don’t have much at all.

More from Rolling Stone

Fall Out Boy Set Aside a Back-to-Rock Album - and Four More Things We Learned From Joe Trohman

From Fall Out Boy to Counting Crows -- Shows Shutting Down While Delta Surges

Watch Rivers Cuomo Cover Fall Out Boy's 'Sugar, We're Goin Down' in New York

And so, as the lore goes, I met Patrick Stump, by chance, at a Borders bookstore in Wilmette. I was with my friend Arthur, and we were flipping through CDs and came across Neurosis, the famed sludge metal band.

Arthur proceeded to ask, “Who is Neurosis?”

Before I could answer, we were approached by a fair-skinned waif of a teen with thick glasses and enormous sideburns – sideburns that looked like they had time-traveled, on their own, from an orgy in the late ’70s to see what future fucking was all about. And this mutton-chopped urchin, he rolled right into our conversation and, unprompted, began explaining who Neurosis was. And my response to this obvious music nerd was to music nerd right back at him. I knew who Neurosis was. Nobody was going to out-Neurosis me, unless that person was Scott Kelly, the singer of Neurosis. Or other members of Neurosis. Or maybe their parents? I don’t know.

And so, as this hairy, elven man talked on, I talked on back. We both liked to talk, that was evident. We both liked to talk about music too. And we both seemed to like each other. We also both liked to hear ourselves talk. And as Arthur sank into the background, slowly morphing into an inanimate object, of sorts, Patrick and I clicked, phasing out the rest of the world so we could connect.

Within our barrage of musical conversations, or perhaps embattlements, I hipped Mr. Patrick Stump to the fact that I was starting a new band with this guy, Pete Wentz. Now, everyone in the punk and hardcore scene in the Chicago area knew of Pete. So Patrick was instantly delighted by the possibility of bestowing his talents upon this new Pete-helmed band. He offered his skills of drumming, bassing, and guitaring. But we needed a singer, I told him. And while hesitant to offer those services (Patrick has always been a reluctant singer), he nevertheless gave me a link to his MP3.com page (yes, that was a real website, before we knew the likes of Grüngle, Stopiphy, TreeFruit Music, and other cute monikers backed by supervillains). Energized, I immediately went home and listened.

The following day I called Pete over to my house to play him a demo by that pale, fuzzy guy who was going to be our new singer. Pete hated it. I relistened to the demo recently (courtesy of Patrick’s hoarder-like propensity to keep everything), and I don’t know what I heard then. Apparently, something. Enough to drag Pete to Patrick’s house, where we forced him to sing and play guitar for us. In fact, we had Patrick play songs from what was our favorite album at the time, Saves the Day’s Through Being Cool—a record that had a massive influence on Take This to Your Grave. Where MP3.com failed, this live, awkward, uncomfortable on-the-spot “tap-dance for me, monkey!” performance won Pete over. It was clear from the start that we had just met our secret weapon, with an undeniable voice.

From there, using my bar mitzvah money to fund the band, we were off to the races, going through a barrage of drummers and second guitarists. And all throughout this embryonic stage of Fall Out Boy, where the only constant members were myself, Pete, and Patrick, I solidified my role as the glue guy, keeping us together, making us rehearse when no one wanted to, trying to push us forward when all felt hopeless, trying to make our terrible band good through sheer brute force.

But we were abysmal. We made bad demos. We then made an embarrassingly bad pop-punk time capsule of an album, Evening Out With Your Girlfriend. You may vehemently disagree with me, and that’s OK. However, I will always consider it no more than a necessary horror. It’s part of our history, but we hated it so much that we almost called the band quits. Then we pulled it back together, thanks to the fact that I pestered everyone to pull it back together through my superpower: annoyance. My voice can drone through anything, and I’m bad at giving up. I feel like a failure naturally, so I never want to feel like a double failure.

Eventually, upon reexamining some of our weak spots, we landed on two big changes: No more second guitarist; Patrick would be singing and playing rhythm guitar from now on. And we needed a good drummer. One who could keep time, perhaps. Maybe even an Andy Hurley type? He’s the guy we wanted all along — easily one of the best drummers in the Chicago and Milwaukee hardcore scenes combined. Everyone wanted him in their band. I’m not even sure how we landed him in our early incarnation of Fall Out Boy. Did I mention we were abysmal?

Andy made us better. His solid backbone drumming made us want to be a better band. Soon after he joined the fold, we tightened the hell up and wrote new songs. Good songs. Songs we weren’t embarrassed about. In fact, we were thrilled about them. Now that we had a real lineup, we felt like we had discovered our sound too. We just needed help recording said songs in a way that sounded good enough to hopefully land us a record contract. Lucky for us, others felt that same way, and we received some financial aid from a local pal, who I will refer to as Bill Givesalot. Bill received a windfall of cash upon his father’s death and believed in what we were doing, enough to lend us thousands of dollars to record at Smart Studios in Madison, Wisconsin — the same studio where albums like Nevermind and Siamese Dream were made.

This led to three of the songs that eventually went onto first real album, Take This to Your Grave. That record was then, and still is, pretty damn good. And at least one record label thought so too. Soon after tracking a portion of that album, we signed to what was once a little-known but well-regarded indie, Fueled by Ramen; finished the sessions; made the record; and toured the living hell out of it. But despite the quality of the album and the fervency of our touring, no one in the industry, outside of our small label and fledgling management, cared much for what we had going on. Luckily, we had the kids. All our burgeoning success at that time we owe to the fans. And we won those people over through not just that album itself but the consistent, hard touring, coupled with explosive, exciting, albeit very sloppy, live shows.

And as the kids followed, eventually the scene came too, as did the industry. While we were still somewhat outcasts, it was becoming clear that we couldn’t be ignored much longer. The gates were being opened, and Fall Out Boy was welcomed into the music industry, though with some trepidation.

It was around this time when my role as the glue guy, the guy who was at least somewhat in charge, alongside Pete, began to waver. Things were getting a little more serious for our fun pop-punk band, as the inklings of a career began to appear in our future. And the more real these inklings became, the more I found myself getting lost in the tides of change.

Everything kept getting bigger. As the success of Take This to Your Gravepropelled the band’s popularity and upstreamed us from Fueled by Ramen to Island Records, the stakes rose, and the necessity to write new songs and produce an expensive major-label album became the focal point. Up until then, we were a down-and-dirty punk band, for better or worse, no matter how you may perceive us. Until that sea change, we were a united front, a motley crew, all on the same page. But as things began to grow out of the DIY and into the mainstream machine, my role in the band, as the person who kept us together and pushed us forward, was becoming obsolete.

I had helped write a bit of music on Take This to Your Grave – not a lot, but some. Patrick was, and still is, the band’s main songwriter, innately talented at crafting hook-laden songs. Naturally, we lean on him for the bulk of our music. But I wanted to write more, to contribute my part. Problem was, songwriting was not something that came as naturally for me, at first. I had to hone that ability. By the time I caught up, it was clear I was too far behind. As the band’s career moved forward at light speed and the need for new material grew, I found myself lost.

I wanted to contribute music and ideas, but I didn’t know how to present them in a way that made sense. I really needed help. But I was too ashamed to request guidance, mortified that I wasn’t producing songs properly, not the way I can today. I was quite young. I didn’t know how to ask for what I wanted, not like a normal, healthy person. Instead, I asked like a tyrant pissant, pouting, stomping, passive-aggressively sneering, not understanding why me being a total drag wasn’t working for anyone.

Dissecting that abhorrent behavior, I think my problem boiled down to the fact that, at one time, I knew who I was, within the confines of the band. But amid new adjustments, I was vacillating in the cosmos of Fall Out Boy, existing on the precipice between wide-eyed, hopeful excitement — that sort of feeling you get on the first day of attending a new school — and dark, dismal apathy—that sort of feeling you get on the second day of attending a new school. Things were about to go from pro-am to the majors for the group, and I was still stuck in pro-am mode.

The moment that the band progressed to Island Records was a paradigm shift like no other. Everything went into hyperdrive once we started production on what would become our breakthrough album, From Under the Cork Tree. And it was at that time that Patrick and Pete had begun to really solidify their sort of Lennon/McCartney duo, to share in each other’s artistic spoils. This was the first time in our band’s short career — four or five years in — that I started to feel a separation and was left to my own devices. So, flailing about, I began to desperately search for new ways into my own band.

We made From Under the Cork Tree in what would be considered an old-school fashion by today’s standards of modern record production. We sat in a rehearsal space with Neal Avron, our producer, and played through songs that were mostly Patrick’s music set to Pete’s lyrics. However, apparently I wasn’t a total lost cause during these sessions. Patrick recently reminded me that I had helped to craft the verses of “Sugar, We’re Going Down” and brought in riffs that became “7 Minutes in Heaven (Atavan Halen)” — small feats that didn’t seem to register with me or make up for my insecurities at the time. While at this current point in my life I feel content with my role and status within the band, back in 2005, I was beginning to feel both inadequate and worthless. I blame some of these feelings on the mismanagement of my own clinical depression. I allowed it to get the best of me, vomiting emotional bile onto everyone in my path. But age and inexperience play a large role as well. I’ve expressed publicly that I did not have the right tools to process my emotions during the early aughts in Fall Out Boy. While that’s true, I am embarrassed that I felt the need to express it so publicly without having my head fully wrapped around the situation.

My behavior during the making of Cork Tree was rough, but things became even more foul during the making of our follow-up, Infinity on High, where I spent most of that recording process, and the tours themselves, consistently high on a combination of OxyContin and morphine, with heaps of bong rips to fill in the gaps. That was the bottom, an extremely dark moment in my life and career. I became a shell of who I once was, nothing more than a dismal drug dumpster.

Ever since I was a kid, I dreamed of being the lead guitarist in a rock band. And by that point, I had achieved it. But looking back on those occasions, when I allowed my pathetic self-pity to become entwined in every waking moment of my life, I wish I could have overcome my demons to enjoy those moments. I wish I had been more grateful for what I had at the time. There are so many bands that work themselves to the bone and never get one-thousandth of what we had then, or now. We were lucky. We are lucky. That isn’t to say we didn’t work hard to get to where we are, but I wish I could have appreciated things back then, as I do today.

I don’t want to give the impression that I ever felt I deserved anything the band had achieved. On the contrary, I never subscribed to the belief that any of what I have been so lucky to accomplish through the band is deserved, and I never will. But years and years ago, when Fall Out Boy began to grow larger than I could comprehend, it felt that this attained dream, of becoming this lead guitarist of a rock band, maybe wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

Suffice it to say, I wasn’t happy with my new role in Fall Out Boy, whether it be on the creative front or live, where I felt like a fabulous dancing donkey, abusing his body onstage for the pleasure of gawking onlookers. I had envisioned that I’d be this man of stature, with a loud, ripping guitar, an extension of, or really a replacement for, my tiny, insignificant prick. Instead, everything at that moment felt nebulous. I was still defining myself by the band, but I did not know my own definition.

I took a lot of my frustration out on the guys. Not that I hit anyone or called them horrible names, but I was a black cloud through and through. I made sure that when they were around me, I would ooze such a sour mood that it would make them feel what I was feeling. That was beyond unfair. I regret that. I regret acting angry and petulant. My lack of self-esteem and confidence fed into a self-hatred that generated unnecessary turmoil. But this wasn’t all about me; I know that. Relationships and dynamics within the band were getting mucky with or without my contributions to the filth. Drugs, unaddressed mental illness, and over-touring helped push us all to the brink of near destruction.

When we went to create the album that preceded our four-year break, Folie à Deux, I tried to reel myself back in. I showed up to preproduction; I was there every day in the studio. I don’t think I had much to contribute to songwriting (I was still somewhat addled from substances), but I did my best to bring bits and pieces and riffs to the recording process. And I really tried to up my mood. It was somewhat fun making that album; I am proud of that one, despite the fact that the record label handled its release poorly.

Despite the somewhat-pleasant recording process, the damage was done within the band. When it came to touring the album, none of us wanted to share a space with one another or be stuck on the road, living that transient, nonscheduled, come-and-go-as-you-please lifestyle. And the fans revolted against Folie. We had middle fingers thrust toward our faces night after night. Bookending it all were copious backstage fights. What about? I can’t totally recall. It was all fueled by burnout. We were burnt out on ourselves. And the world seemed burnt out on us. So we did what anyone would do when they feel not wanted: we went away.

Time apart from Fall Out Boy was needed. It gave me an opportunity to work with my new band, the heavier, less commercially dependent The Damned Things. I wrote the majority of the music for that first album, Ironiclast, which thrust me into a position of leadership, instilling a fair amount of self-confidence that I was able to bring back to Fall Out Boy, eventually. So nearly four years after announcing the famed hiatus, Fall Out Boy ushered in our return and made SaveRockandRoll. And this time, I brought music. Lots of it. I fought for things, in a communicative, healthy manner — free of anger and hard drugs. I did my best to be a part of the team and reassert myself. On top of that, I tried to stay positive. I had spent the prior four years not just working on my creative self but working on my mental health.

I did a re-up on my SSRI medication, got into regular therapy, and learned how to find an identity for myself that could exist on its own, outside of anything related to work — whether it be music or otherwise. I was intent on finding an inner peace of sorts, not necessarily in a traditionally Buddhist sense, but I wanted to know how I could be happy with me: Joe, the curly-haired, aloof, part–Mel/Albert Brooks, part–Jeff Spicoli guy in the corner. I learned that I felt lost because I lost myself, allowing my personality to be conflated with my band. I am not Fall Out Boy. And Fall Out Boy is certainly not me. Not by a long shot. And by fully realizing and coming to terms with that, I found some freedom.

When Fall Out Boy started making our eighth studio album, Mania, I did my best to assist, but that one sort of went off the rails for me. I feel that it’s not our best effort, and I’m being kind. Don’t get me wrong; there were some good ideas on there, and a song or two of worthwhile note. But in a way, it’s a depiction of the band desperately searching for its own identity. I had become so content with me, with what I had going on, engrossed in making a second The Damned Things album and developing projects for television (not successfully, but having a ball trying), that I was OK with allowing everyone else to take that album in whatever direction it was to go in. I suppose I could’ve worked harder, yelled louder, fought, and done whatever else could have been done to make Maniaturn out in a way I would’ve preferred, but I wasn’t interested in the stress. I could see that if I thrust myself into that particular rat’s nest, the old me, the black-cloud me, would come back out in full force. And I didn’t need that. No one did.

Not everything can be a win. And that’s OK. Some albums are good. Some are shit. Some art is art. Some art is trash, even if you thought it was a Monet sandwiched between a Pollock and a Renoir. And one must learn that, especially within a collaborative creative environment, you don’t get to do everything. You must find your lane, what works for you and those around you. And in Fall Out Boy, I’m OK helping when I can, where I can, and getting out of the way when need be. Nineteen-year-old me would have retched at that idea, being a selfish, entitled blowhard who wanted to show the world how great he was. Well, you know what, teen me? Fuck you. You’re the fucking worst. I’m glad I’m not you anymore. I’ve got a beard now and thick man skin. Fear me. Come get some, bitch! I’d kill you if you weren’t already dead!

As I jot these thoughts down, I feel a sense of overwhelming serenity. I mean, who the hell gets to do what I do? I’m so lucky. I play guitar for a job. And I can support my family doing so. Plus, being able to bring happiness, in the form of song, to thousands of people a night, it feels like a public service. I’m not self-aggrandizing here; I realize people spend their hard-earned money to be served. But it’s that exchange of energy, that life-affirming social experiment of playing live for a crowd, giving your all while they give the same back—what a wonderful thing.

For the first time in my short life, I can reflect upon my two-decade career in my band with pride: the good, the bad, the disgusting, and the abysmal. The embarrassing outfits. The unfathomable haircuts. The songs that have become classics for some. The ridiculous kissy-face photos for teen rags. The interviews where I completely let my guard down and talked about being a pathetic, spineless twerp. That time we played SNL and, instead of trying to sound good, thrashed around like morons. Those times we got to play Letterman a bunch. And that one time when Jay-Z introduced us onstage. That time I vomited inside our van, all over everyone, because I thought drinking an entire bottle of Bushmills was safe to do. I’m proud of it. All of it. Except that awful cover of the original Ghostbusters theme. Sorry!

Excerpted from NONE OF THIS ROCKS: A Memoir by Joe Trohman. Copyright © 2022. Reprinted by permission of Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc., New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Best of Rolling Stone

money

money