Dishing up history: Chicago woman donates 'priceless' collection of cookbooks to culinary program

Bouillabaisse is a dish best made for a crowd, so maybe it's no surprise that after decades of cooking, the Provençal fish stew remains Sandra McWorter Marsh's favorite recipe, a testimony to the lifelong Chicago resident's passion for feeding others.

“It was always so pleasing to the palate,” Marsh said. “And it never seemed to fail.”

Marsh, a retired graphic designer who turns 82 in June, found joy in the cookbooks she collected through the decades, taking recipes and molding them to her whims.

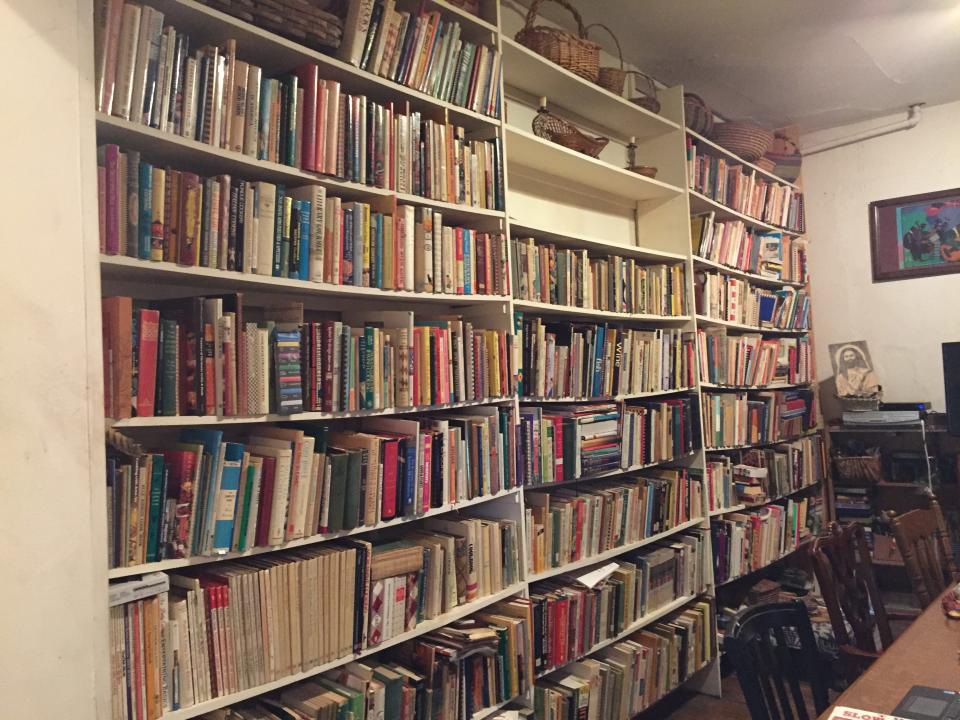

But health problems, namely a debilitating brain tumor, would finally render her beloved cookbooks unusable. Earlier this year, she and her brother, Abdul Alkalimat, donated the collection – nearly 1,800 in all – to the Washburne Culinary & Hospitality Institute at Chicago’s Kennedy-King College, one of the nation’s oldest culinary schools.

More than a collection of recipes, the books are a reflection of history, dating from the early 1930s to the late 2000s and showcasing the knowledge, technique and ingredients of bygone eras.

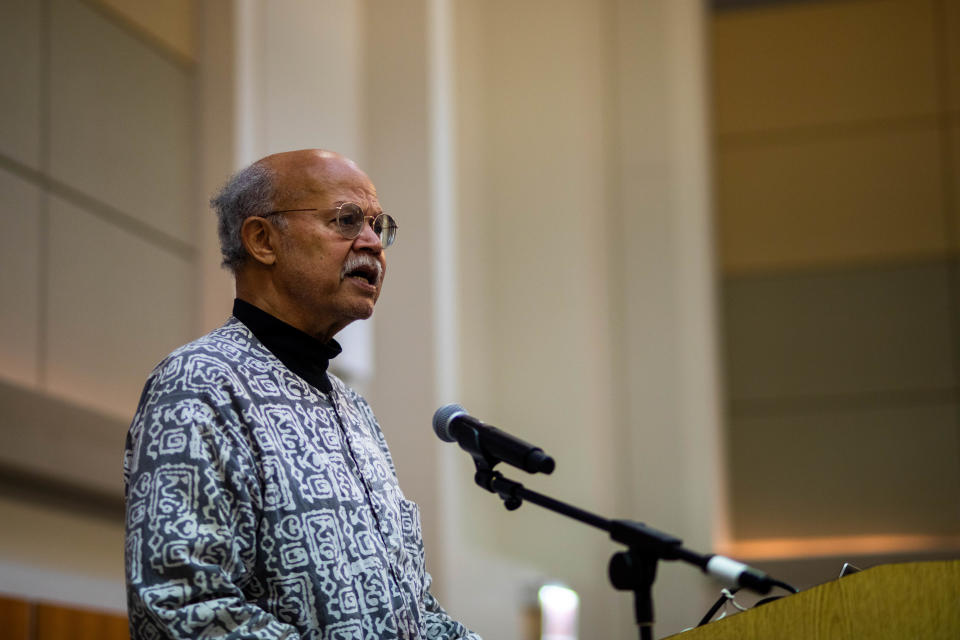

"Cookbooks are really cultural artifacts," said Alkalimat, professor emeritus of African American studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The books range from classic titles and multivolume sets to regional recipes and homespun pamphlets foraged on Marsh’s many travels.

“It’s an encompassing of culinary traditions from the last 70-plus years,” said Adam Carey, who chairs Kennedy-King’s library department. “That’s why this collection is so incredible.”

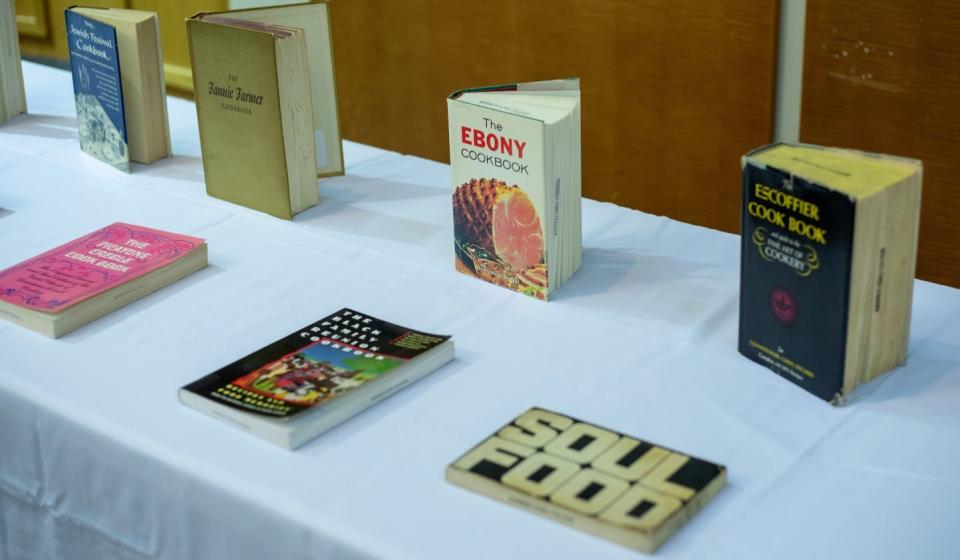

A healthy portion of the collection, Carey noted, spells a narrative of 20th-century Black America through dishes, methods and nods to community celebrations such as George Washington Carver Commemoration Day. Some of those titles include “A Date with a Dish: A Cook Book of American Negro Recipes” (1948); “Soul Food” (1969); “The Black Gourmet: Favorite Afro-American Recipes from Coast to Coast” (1984); and “The Black Family Dinner Quilt Cookbook” (1993).

The siblings said they chose Washburne for its Chicago South Side location and multiethnic, working-class population. Black students have comprised 53% of students at the school over the past several years; Latinos represent another 34%, according to City College of Chicago data.

“We were interested in giving back to people we identified with,” Alkalimat said.

Historic family connection

The two come from one of Illinois’ most storied families: Marsh and Alkalimat are great-great-grandchildren of Free Frank McWorter, a former Kentucky enslaved person who purchased freedom for himself and 15 family members and in 1836 founded New Philadelphia, Illinois, the first known municipality to be established and platted by an African American.

The town, which lives on only in archival documents, artifacts and oral histories, was designated a National Park Service site last year.

“The McWorter family is, from a historic perspective, one of the most incredible families in Illinois,” said City Colleges of Chicago Vice Chancellor Rhonda Brown, who oversaw the donation.

At an event in February to honor the siblings’ gift, attendees enjoyed a meal gleaned from the cookbooks and prepared by the school’s culinary students. Along with jambalaya and barbecued grilled chicken, the luncheon featured two dishes from the National Council of Negro Women’s “The Black Family Reunion Cookbook," including a strawberries and mint appetizer contributed by U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters and a vegetarian black-eyed peas and rice recipe from Susan L. Taylor, Essence magazine’s then-editor-in-chief.

By next year, the school hopes to tap Marsh’s cookbooks for use in community cooking classes.

“Value-wise, it’s almost priceless,” said Carey, the library director. “To make sure they are accessible to the greater campus community for generations to come is really an awesome honor.”

'A diva in the kitchen'

While bouillabaisse can be fancied up with the finest seafood, it evolved as a simple Mediterranean fisherman’s soup, as culinary legend Julia Child reminded in her 1961 book, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.”

Marsh varied hers according to the freshest seafood she could find at Chicago's Market Fisheries on State Street, dressed with parsley or basil pulled from the raised garden in her back yard.

“It was a like a tune she could play all these different ways,” Alkalimat said. “And like a lot of cooks, she was a diva in the kitchen.”

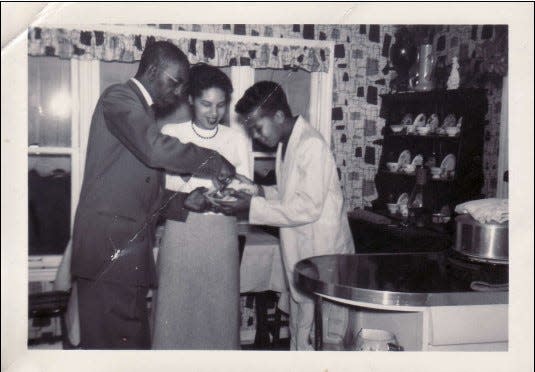

The two grew up in Chicago’s Francis Cabrini Homes public housing project, absorbing their parents’ global tastes and interests. Their backyard, Alkalimat recalled, abutted that of future jazz great Ramsey Lewis, and “we’d be on the corner singing doo-wops to the older kids. We were eating snails before we knew it was escargot.”

Their father, he said, was “the barbecue king of the neighborhood,” and as kids, they remember him tending one of the estimated 20 million World War II “victory gardens” that citizens were urged to cultivate to combat produce shortages. Later, they learned canning from their Aunt Ellen in Kansas City.

Those experiences “really taught us tremendous lessons: the ability to define your quality of life through your own efforts,” Alkalimat said.

It was the 1931 classic “Joy of Cooking” that had lit Marsh’s spark for culinary arts. “That was the first book I remember collecting,” she said, and she would ultimately count four editions among her collection.

When she and Alkalimat studied at the University of Chicago, they shunned happy-hour invites in favor of hosting friends at Marsh’s apartment over spicy fried gizzards and gin and tonics. As her cookbook collection grew, so too did her spirit for entertaining and her fascination with the commonalities that bound other culinary traditions to her own.

Marsh enjoyed making the macaroni and cheese recipe her niece always demanded, excelled at reinventing leftovers, and was forever on the lookout for good recipes for peanut brittle, one of Alkalimat’s favorite treats. But one of her favorite creations was a roast rabbit with mushrooms and shallots from a book dedicated to nose-to-tail cooking – the now-trendy concept of using every edible portion of an animal that was at the foundation, by necessity, of Indigenous, soul food, Southern and other cuisines.

“Every part of the animal is used,” Marsh said. “The focus is on using it all to the advantage of the dish. There’s nothing more exciting than knowing how our food developed.”

Her collection ranged from African, European, Mediterranean and Latin American traditions to Jewish, Caribbean, Hawaiian and vegetarian cooking. Some books focused on specific foods – bread, corn, potatoes and wild game, while others highlighted the latest gadget of the time.

“I was an easy person to give gifts to,” she said.

Those books sat on Marsh’s shelves alongside more revered titles – "The Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook" (1982); a 1965 copy of “The Fannie Farmer Cookbook,” and a 1941 edition of a cookbook by renowned French chef Auguste Escoffier.

But all of it revolved around feeding family and friends. As Alkalimat remembers: “Her usual comment when someone came to the house was ‘Do you want something to eat?’”

A beloved collection finds a new home

In Child’s version of the dish, the bouillabaisse broth is brought to a boil, then in go any firm-fleshed fish, followed by quicker-cooking tender-fleshed fish and shellfish. “Bring rapidly to the boil again and boil 5 minutes more or until the fish are just tender when pierced with a fork. Do not overcook.”

In other words, you have to know when it’s time to stop, and for Marsh, the time to lay down her saucepans and ladles gradually set in as her tumor pressed harder on her optic nerve, hampering her vision. When the cookbooks were plucked from their places and packed up for donation, they filled 75 boxes in all.

Living in a Chicago-area senior living facility where meals are served at the same time every day, Marsh longs for those days of creation and spontaneity.

“That’s one thing I really miss doing is cooking,” she said. “And sharing things with other cooks when you’ve discovered something new.”

She hopes the collection will endure in Kennedy-King's culinary program and the local community.

"It just seemed like a place where they could find a happy home."

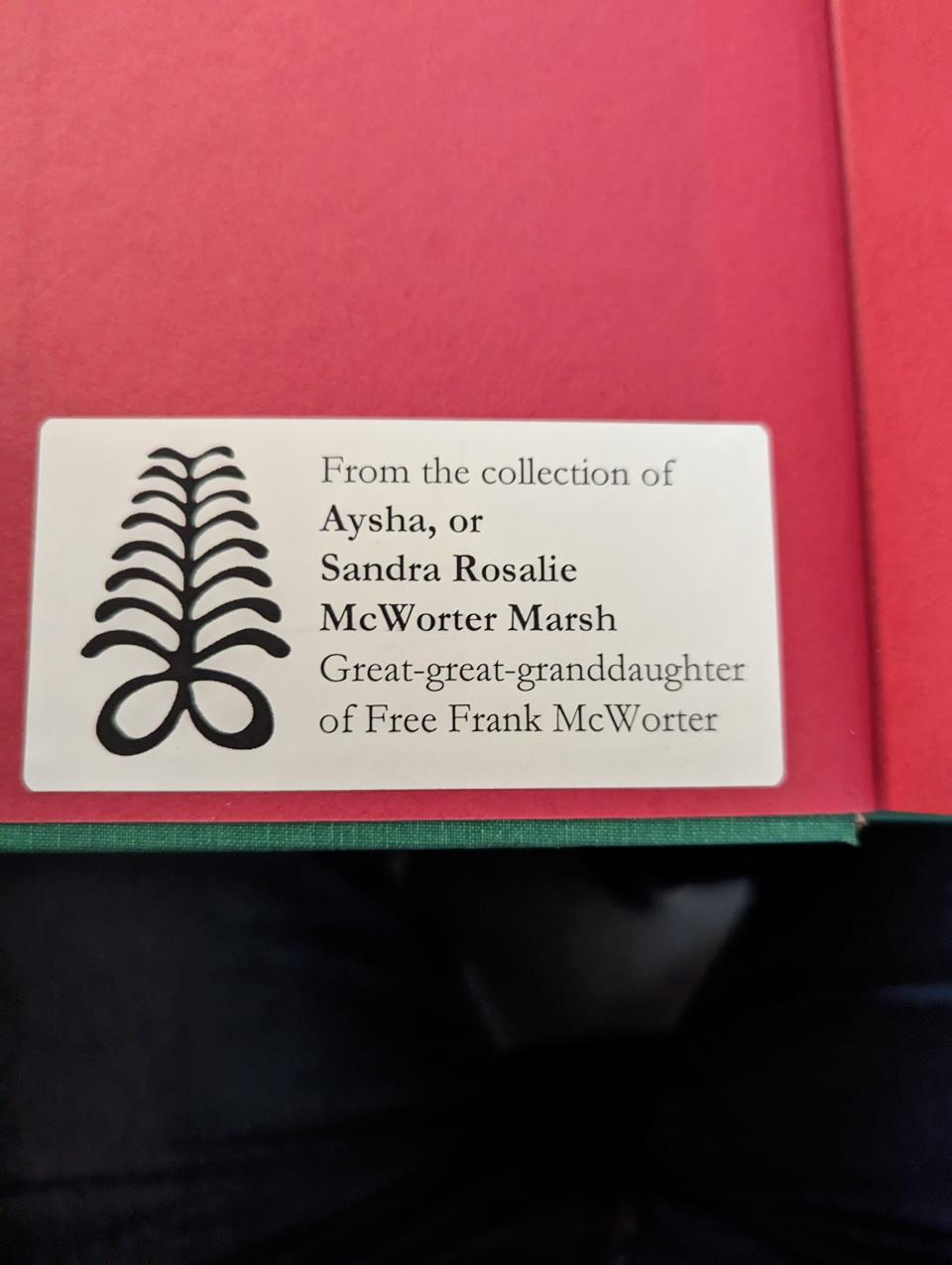

The books are being integrated into the culinary arts section of Kennedy-King’s library, fitted with custom book plates detailing their origins as part of Marsh’s donation, and Alkalimat said he has been heartened to hear from students who have made time to stop by and peruse the collection.

Carey, the librarian, said that while some books border on mint condition, others among Marsh’s trusty core show the spatters, scribbles and dog-eared pages of faithful use.

“There’s very definitely some marginalia, notes and things that are difficult to decipher,” he said. “These books were very well loved. That is what we as librarians like to see: A used copy is the greatest reflection of a book’s life. They weren’t just stored on a shelf. They were handled and loved.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Chicago woman donates 1,700 cookbooks to urban culinary program

money

money