What They Didn't Teach You In School: The Assassination Of Medgar Evers And The Murderer Who Walked Free For Three Decades

To continue with BuzzFeed's Black History Month True Crime Series, I chose to dive into the life, activism, and death, of Medgar Evers.

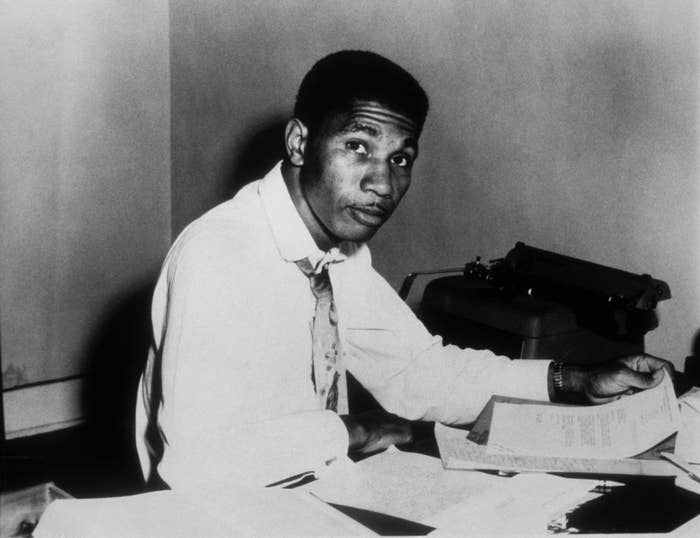

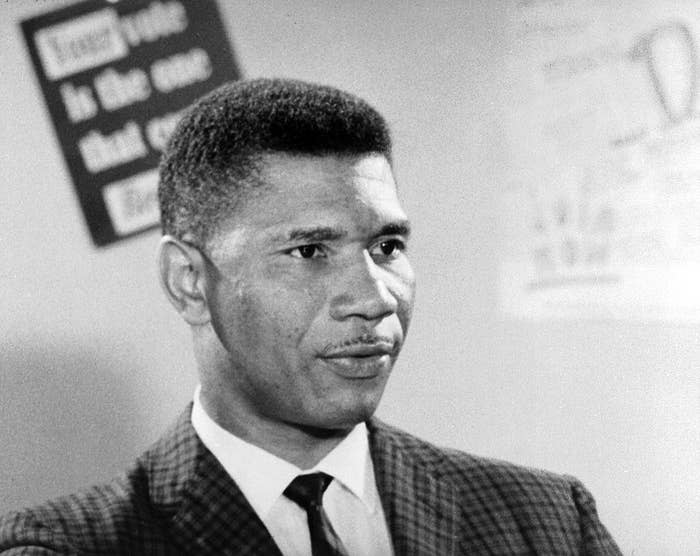

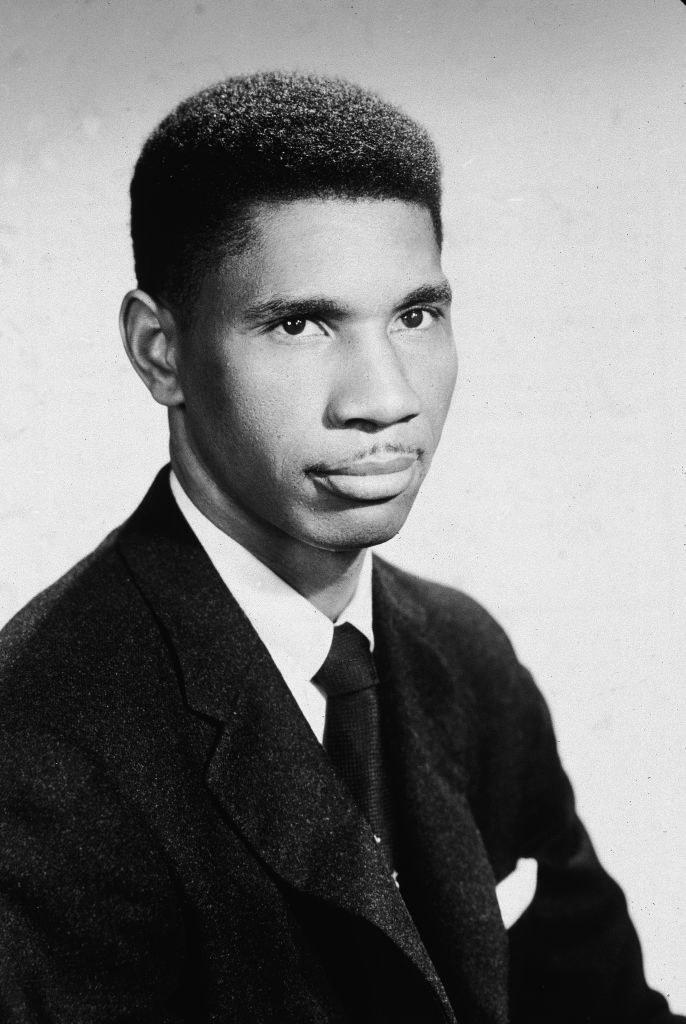

Medgar Evers is one of the most important Civil Rights activists in American history. He fought against Jim Crow, was the NAACP's first field officer in Mississippi, and spearheaded investigations into some of America's most egregious racial crimes, including the murder of Emmett Till.

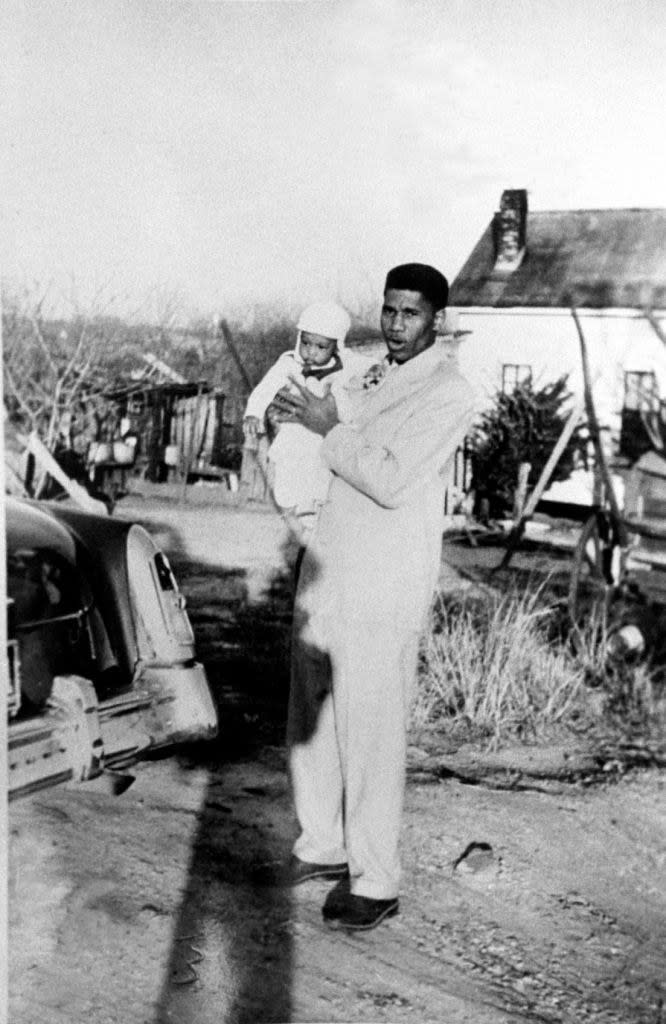

Medgar was born July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi to James and Jesse Evers. He was one of four children, but he formed a close bond with his older brother Charles. James found work in a sawmill, while Jesse was a laundress.

Jesse and James hammered home the importance of education, while Charles taught young Medgar skills such as hunting, boxing, swimming, and fishing.

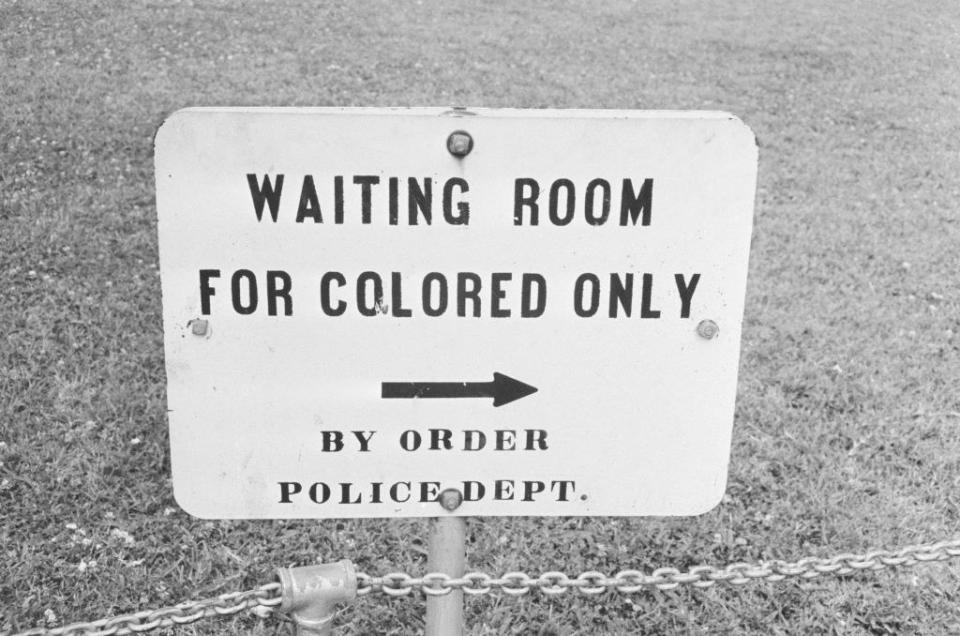

Medgar and his brother would walk several miles to their segregated school, as they were not allowed to attend school with white children. In The Martyrs: Sixteen Who Gave Their Lives for Racial Justice, Jack Mendelsohn quoted Evers on his childhood. "I was born in Decatur here in Mississippi, and when we were walking to school in the first grade white kids in their school buses would throw things at us and yell filthy things," Evers stated. "This was a mild start. If you're a kid in Mississippi this is the elementary course."

And unfortunately, he was right. Growing up in a segregated Mississippi forced Evers to witness some of the most brutal forms of racism.

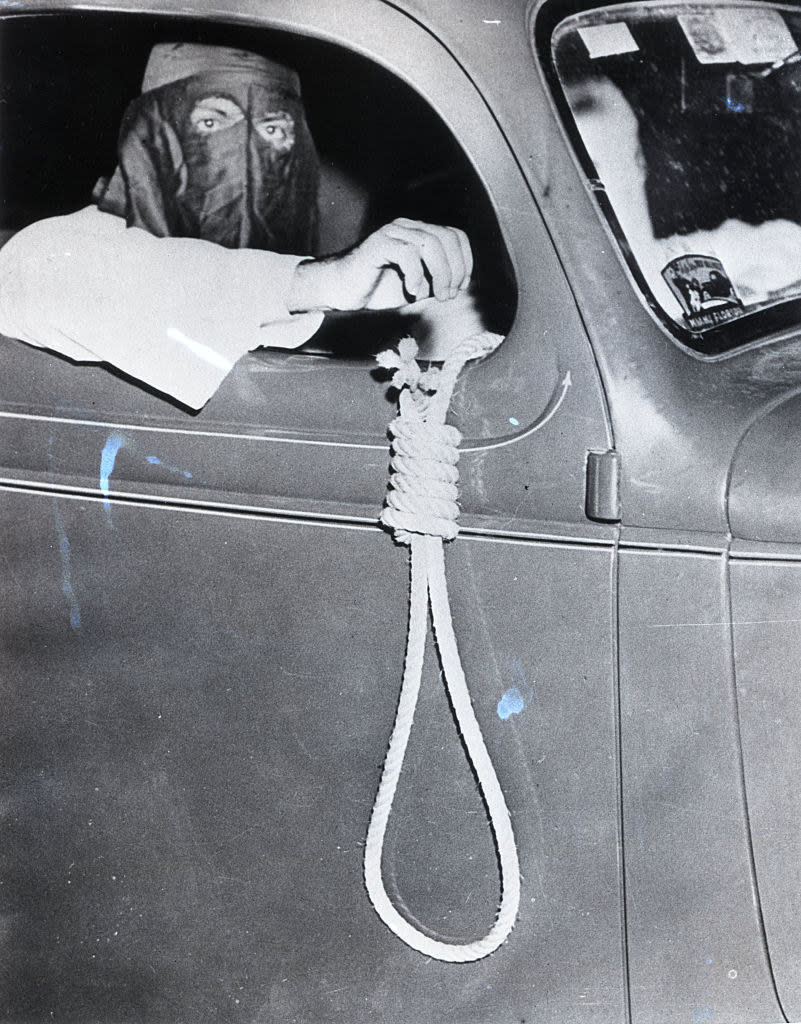

"I graduated pretty quickly," Evers continued. "When I was eleven or twelve a close friend of the family got lynched. I guess he was about forty years old, married, and we used to play with his kids. I remember the Saturday night a bunch of white men beat him to death at the Decatur fairgrounds because he sassed back a white woman. They just left him dead on the ground. Everyone in town knew it but never [said] a word in public."

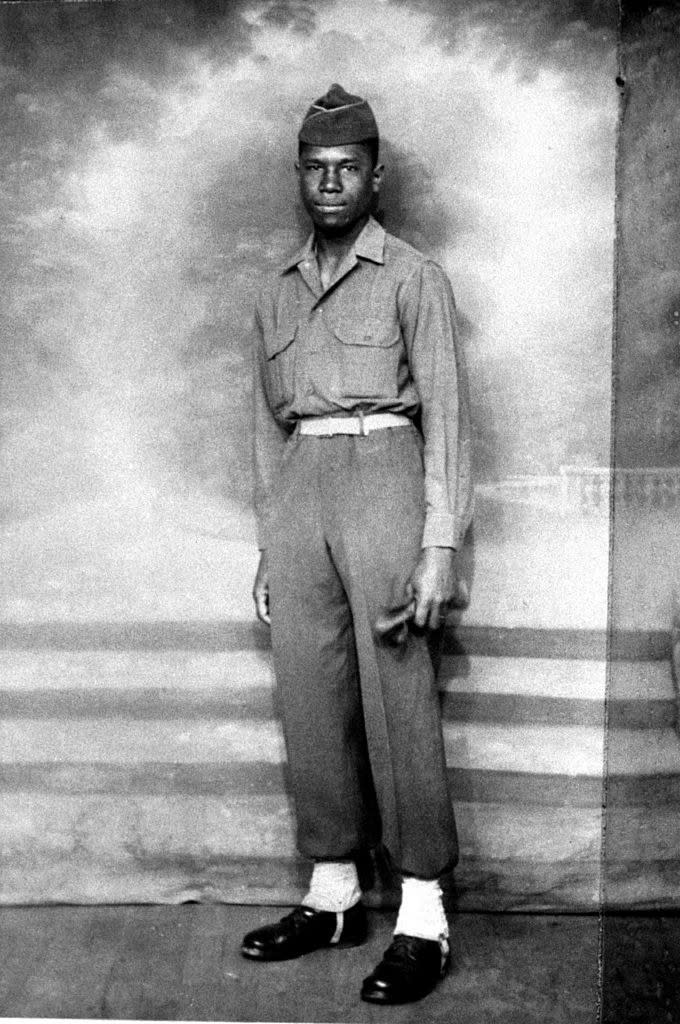

Medgar was drafted into the Army in 1943, which would make him a ripe young 18-year-old at the time. He was inducted at Camp Shelby, in Mississippi, and fought in World War II. Medgar was placed in a segregated portion of the Quartermaster Corps, which further exasperated him.

Medgar, a Technician Fifth Grade, served in both England and France but became disillusioned with the military due to the racist treatment the segregated Black soldiers were subject to while fighting for their country. He was honorably discharged in 1946, and returned home to fight a war he felt was more pertinent to himself: the war against systemic and institutional racism.

After returning from World War II, Medgar found that he would not be treated with the same respect as white veterans back home either. Medgar registered to vote, but found resistance when he and his brother tried to exercise their right. Medgar, his brother, and a handful of their friends were threatened at gunpoint when attempting to vote in a local election by over 200 white men. Often, racist whites would try to intimidate Blacks who went to vote, and it would get violent quite frequently.

"All we wanted to be was ordinary citizens," he stated in Martyrs. "We fought during the war for America and Mississippi was included. Now after the Germans and the Japanese hadn't killed us, it looked as though the white Mississippians would."

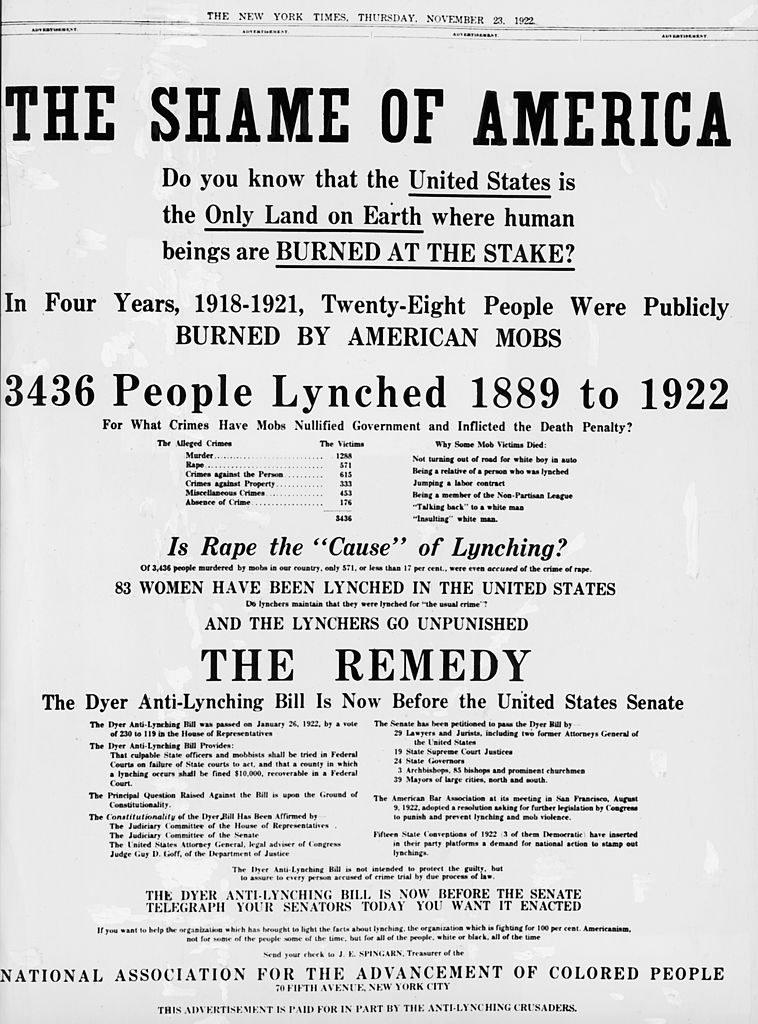

Although Medgar was blocked from voting, this only set the fire in his chest ablaze with more determination than ever. He and his brother Charles would register for the NAACP with the motivation to help disenfranchised Black citizens gain proper access to voting. The NAACP had already garnered a reputation for pushing back against lynchings and other acts of racial violence, and Medgar found himself drawn to their passionate and genuine fight for equality.

Medgar knew that his education would also play a huge role in helping Black Americans secure better rights. So, he attended the HBCU Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, which is now called Alcorn State University. It was here that he met Myrlie Beasley, and fell in love.

"I was very curious about him," Myrlie said of Medgar. "We saw each other in passing at school, particularly at the gymnasium, which was also our food service area. One day he asked me to sit with him, saying, I just want to talk. I thought, 'Fine, there’s no harm in talking.' He proceeded to tell me — and I quote — 'You will be the mother of my children.' I was 17 years old and had barely even dated."

Myrlie and Medgar would get married in 1951 and the following year, after he graduated, the two would move to Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Medgar worked selling life insurance, but quickly became entrenched in activism. He witnessed an attempting lynching in 1954 that would further encourage him to work on securing rights for Black Americans.

At the time, Medgar's father was very ill and in the hospital. While visiting his dad, Medgar ran into a mob of angry racist white people outside. "On that very night a Negro had fought with a white man in Union [Mississippi] and a white mob had shot the Negro in the leg," Medgar stated in The Martyrs. "The police brought the Negro to the hospital but the mob was outside… armed with pistols and rifles, yelling for the Negro. I walked out into the middle of it.… It seemed that this would never change."

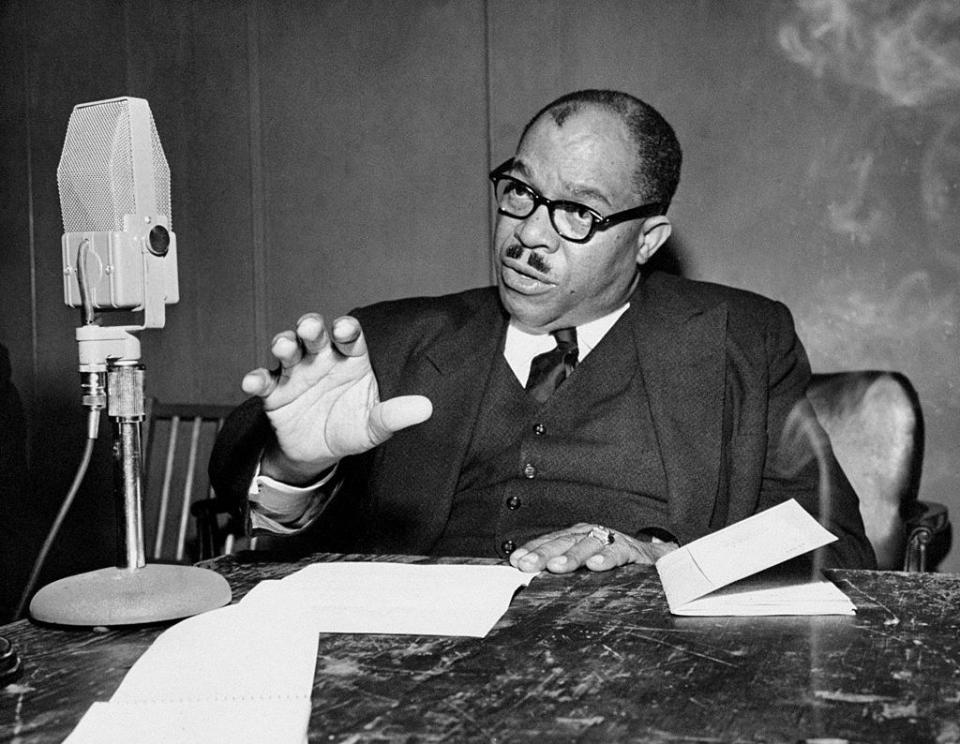

Medgar ended up becoming involved with The Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL) in Mound Bayou, a predominantly Black town that was created by former slaves. The RCNL was founded in 1951 by Theodore Roosevelt Mason Howard, an intelligent and wealthy businessman. The Civil Rights organization attracted the attention of Medgar, as he worked alongside Howard in the insurance business.

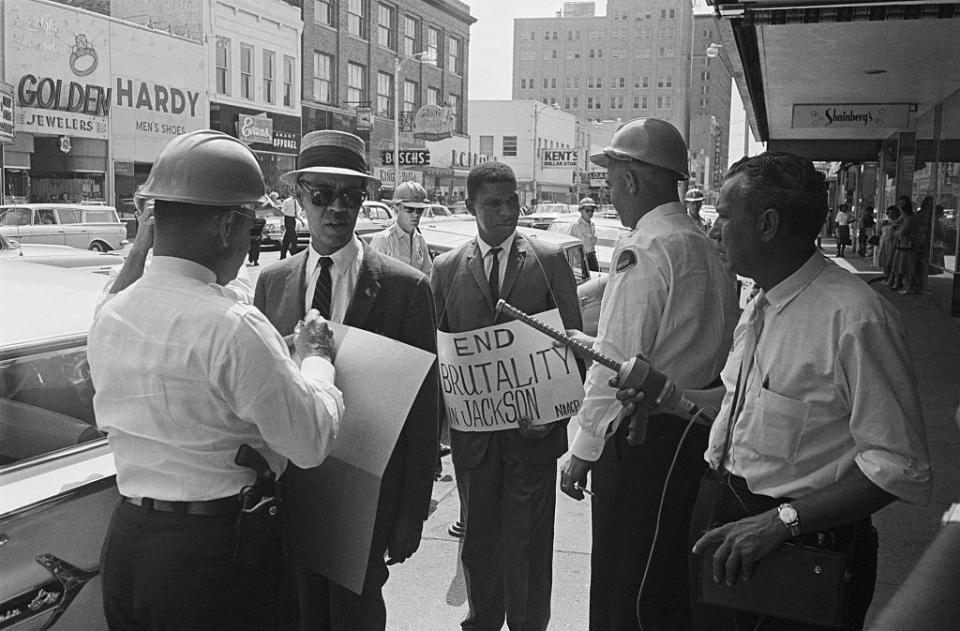

The RCNL staged boycotts against gas stations that banned Black people, organized protests against police brutality, and also orchestrated several drives to encourage Black Americans to register to vote. Working within the RCNL gave Medgar his first real experience at organizing large events in the name of Civil Rights.

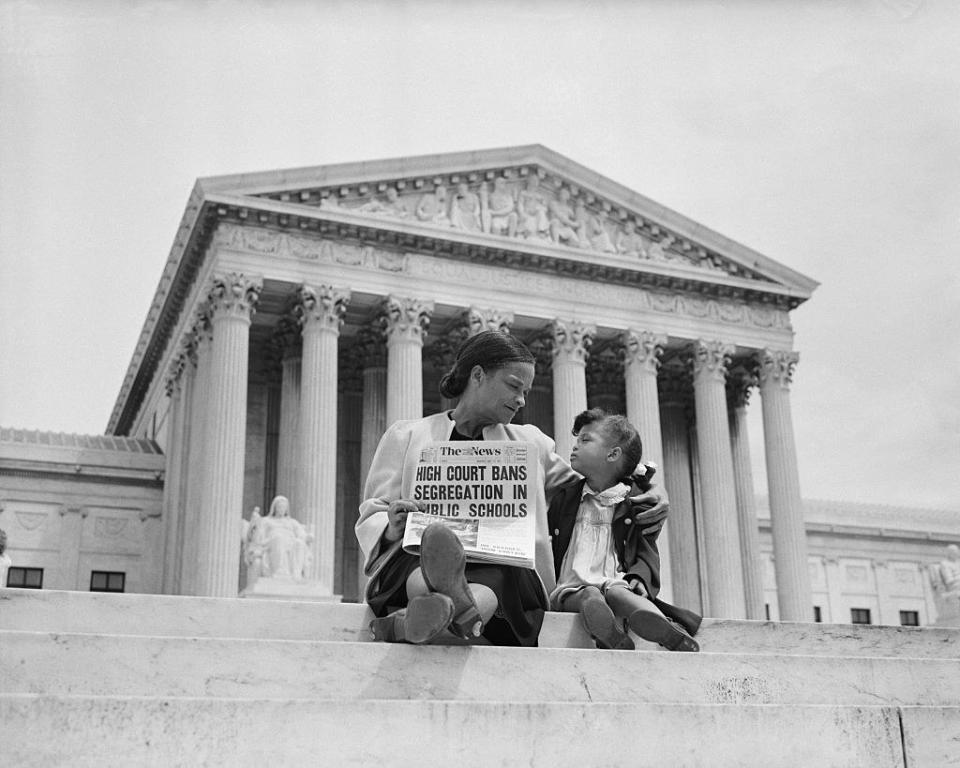

In May 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court made the landmark decision in the famous Brown v. Board of Education case. This legally desegregated schools, although the decision was on paper, and the real-life process of desegregation was a much bigger battle to be fought. Of course, schools across the nation were VERY resistant to the Supreme Court's decision.

In response to the Brown vs. The Board of Education decision, white supremacists in the south created the White Citizens’ Council (WCC). It was a violent "political" body that would use its influence to make sure Blacks stayed segregated.

Medgar applied to the University of Mississippi Law School, however, he was rejected because he was Black. Undeterred, he would continue his work with the NAACP by filing a suit against the school. Although the lawsuit failed, he would later help another Black student fight his way into the University.

When Medgar and Myrlie moved to Jackson, Mississippi, the couple's activism would take another leap forward. Medgar was appointed as the NAACP's first field officer in Mississippi in 1954. In this role, Medgar was involved in a few very high-profile cases.

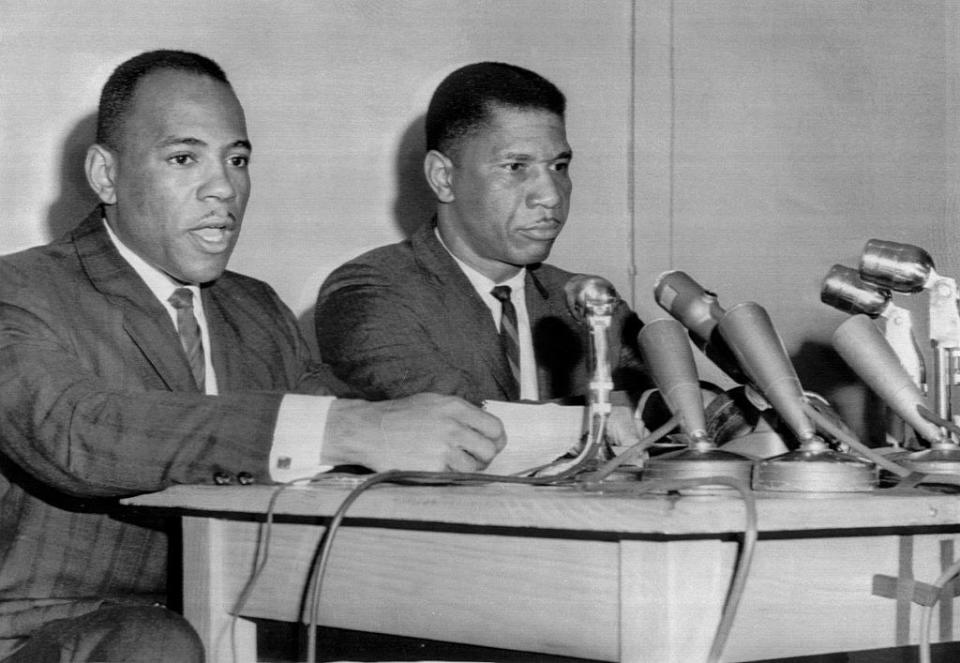

One such case was that of James Meredith, who became the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, the same college that denied Medgar entry.

In 1961, James applied to the University of Mississippi, and although he was at first accepted, his admission was rescinded after the school learned of his race. James filed a lawsuit for discrimination, which failed in the state courts. However, Medgar was able to bring the NAACP's legal team into the battle, which was headed by Thurgood Marshall. Thurgood was the chief attorney for the plaintiffs in the Brown vs Board of Education, so he already had expertise dealing with cases of this magnitude.

James' case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in his favor. However, when James went back to the University to enroll in classes, he was met with blockades and riots, which left two people dead. Angry mobs of racist whites flew Confederate Flags as they destroyed property and attacked anyone supporting James. Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent U.S. Marshals, while President John F. Kennedy dispatched the military to assist with the deadly situation. 160 of the U.S. Marshals were wounded, 28 of them shot. Finally, the military was able to get a handle on the situation and James was able to enroll in 1962.

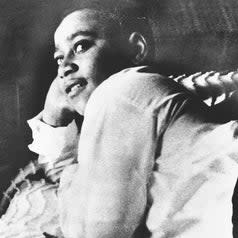

Another prominent case that Medgar was monumental in was the investigation into the murder of Emmett Till.

In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett was visiting relatives in Mississippi and stopped in a shop along with his cousins. A white woman, Carolyn Bryant, claimed that Emmett whistled at her, grabbed her, and was sexually menacing. Several decades later, Bryant would admit that she lied about those claims. However, at the time, she stuck with her story. Her husband, Roy Bryant, and brother-in-law, J.W. Milam, abducted, tortured, and murdered Emmett. They tied a 75-pound cotton gin fan around his neck and tossed him into a river. His body was recovered, bloated and beaten, and his mother, Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley, held an open casket funeral to alert the world to the brutality of racism in the south.

Medgar opened an investigation into the murder, urging any Black witnesses to come forward despite the danger they would be in by speaking out. After securing Black witnesses, Medgar and T. R. M. Howard helped protect them throughout the trial, even assisting them in escaping the town after things had concluded. Despite all this work, J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant were acquitted, and Howard was placed on the KKK's death list... he was forced to flee Mississippi.

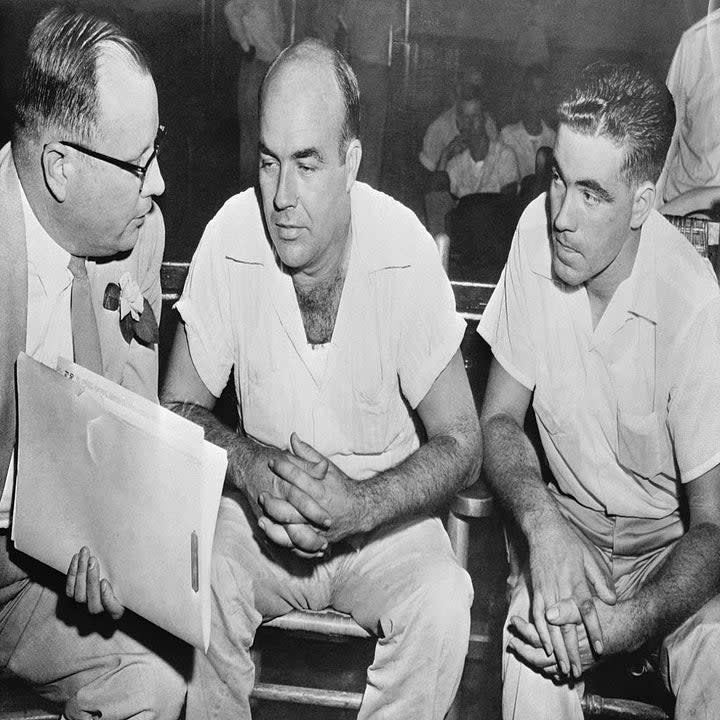

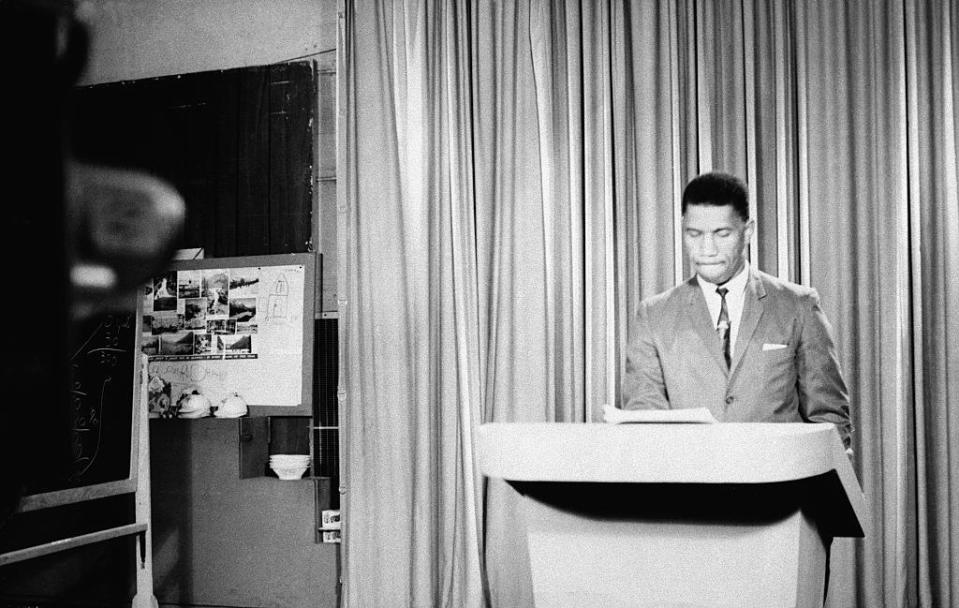

In the first image above, J.W. Milam (center) and Roy Bryant speak with their attorney during the trial. In the second image, you can see T.R.M. Howard with the witnesses he and Medgar secured. No one was punished for this horrific murder.

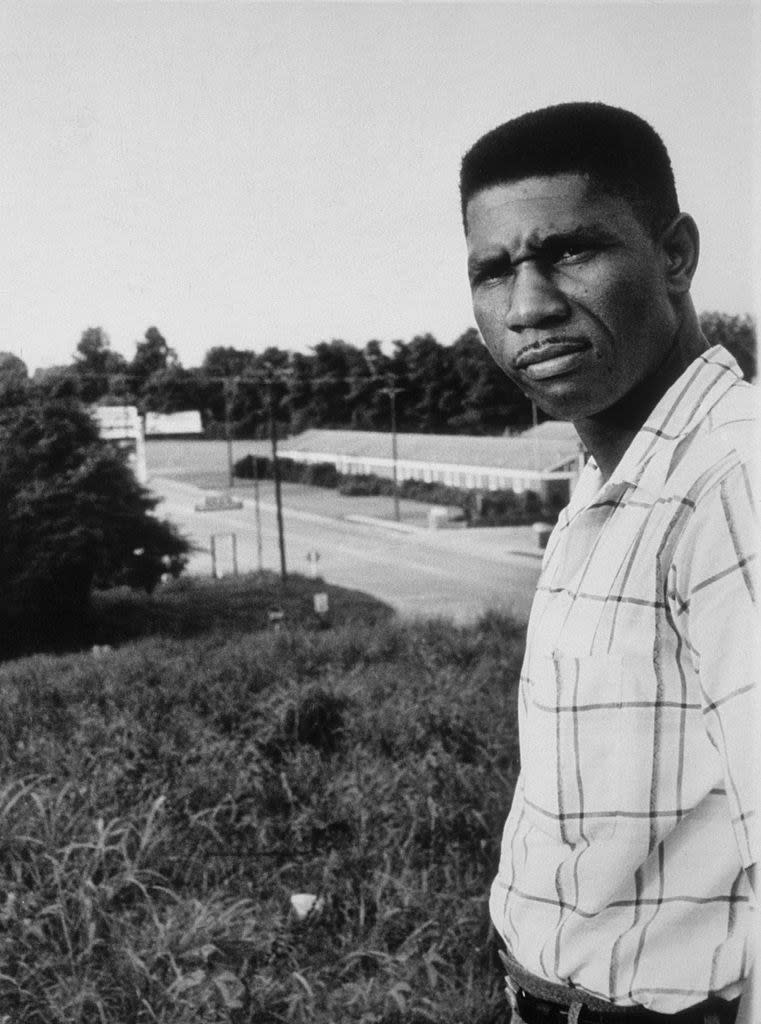

Medgar also fought to clear the name of Civil Rights activist Clyde Kennard. Kennard was another activist who tried to push back against segregation in the south, by applying to become the first Black person to attend Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi). Instead of admitting him, in 1960 the state framed him for petty crime, and sentenced him to seven years in jail. An all-white jury convicted him in ten minutes.

While in jail, Kennard was diagnosed with colon cancer, and Medgar (along with other activists) pushed for his release. So, in 1963 Kennard received clemency on medical grounds and was released, although he died just a few months later. “Despite the overwhelming evidence in Clyde Kennard’s favor, … the greatest mockery of justice took place …. In a courtroom of segregationists apparently resolved to put Kennard 'legally away,' the all-white jury found Kennard guilty as charged in only 10 minutes," said Medgar at the time. In the early 90s, the University of Southern Mississippi owned up to its part in the racist tragedy.

Medgar's involvement in such high-profile cases put him in the crosshairs of the KKK. White supremacists attempted to kill him many times. His home was firebombed in May 1963, and his family was threatened on several occasions. On June 12, 1963, white supremacists made good on their threats and murdered him.

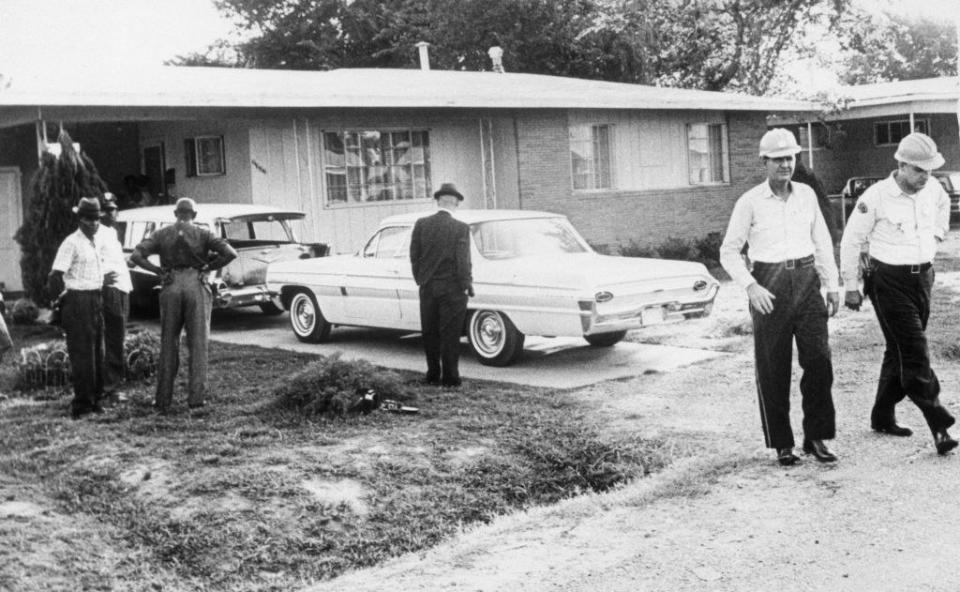

On that fateful night, Medgar had just gotten home. After parking his car and walking up to his home, he was shot in the back. His family, who was home, heard the gunshot and found Medgar in the front yard. He was taken to a hospital but died within the hour. Just moments before his murder, President Kennedy had addressed the nation on the importance of the Civil Rights movement.

Medgar was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Medgar was often escorted home by FBI and police officers for his own safety, however, on the day of his assassination he arrived home without the escort.

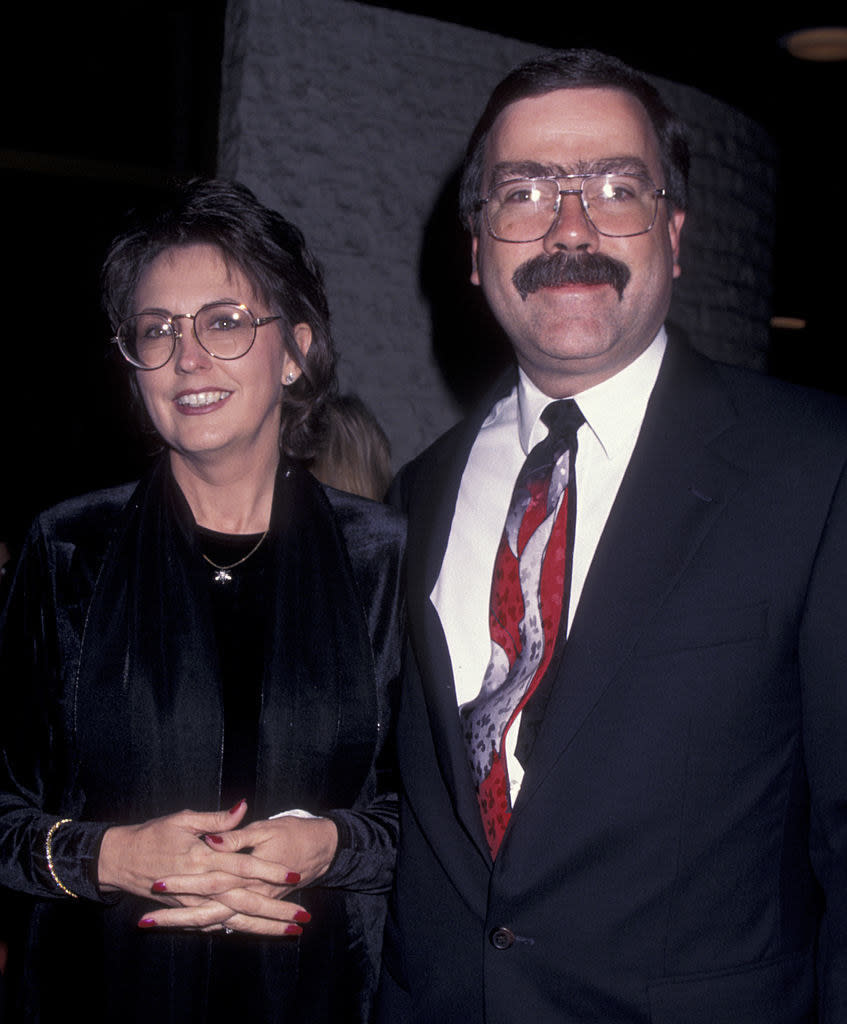

Byron De La Beckwith, a founding member of the White Citizens Council in Mississippi, was soon named the prime suspect in the assassination. Local police found the rifle used in the murder near Medgar's home, and also discerned that it had recently been fired. Fingerprints on the rifled were immediately connected back to Byron, based on his military prints on record. Witnesses had also claimed Byron had been asking around about Medgar's address. He was arrested several days after the murder, and had an injury around his eye consistent with the recoil of shooting a rifle while looking down the scope.

Three trials were held in an attempt to convict Byron. Before the first one, Byron was sent letters of support and money for his defense. During the first trial in 1964, two police officers claimed to have seen Byron in Greenwood, which is roughly 90 miles from Medgar's home, on the night of the assassination. Byron also claimed his gun was "stolen" before the murder. An all-white jury was unable to reach a verdict. A retrial was slated for later that year, but also resulted in a deadlock. Once again, an all-white jury could not come to a decision and Byron was set free.

Myrlie was determined to get justice for her husband though. She moved the family to Claremont, California, and earned a degree from Pomona College. All the while, she continued to dig for evidence.

“They were awake that terrible night, and heard the thunderous roar of the death shot," wrote Myrlie of her husband's assassination. "They saw their father lying in a scarlet pool of blood as his life ebbed away… So it was that in the spring of 1964, while on a speaking engagement in California, I asked friends to ‘look around’ for a house for me.”

Myrlie soon found the evidence she needed. In 1989, The Clarion-Ledger, a newspaper in Jackson, documented how in 1964 a legal state agency that supported segregation assisted Byron's defense team in screening jurors for both trials against him.

Further investigation determined there was no jury tampering. "So far, there is absolutely no evidence to indicate jury tampering," assistant district attorney Bobby DeLaughter stated at the time. "None were contacted. None were even aware that any contact had been made with their employers until after the fact."

However, the investigation was able to uncover new witnesses that claimed Byron bragged to them about the murder. He was indicted for the murder for the third time in December of 1990.

Byron tried to fight this indictment for years by claiming it violated his rights to a speedy trial, due process, and security from double jeopardy. He asked for all charges to be dropped, but was denied in 1993. Since his first two trials were mistrials, and not acquittals, he could not use the double jeopardy argument. The third trial was set for January of 1994.

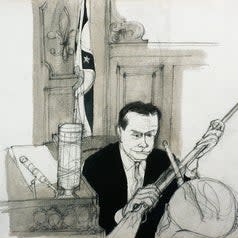

Medgar's body was exhumed and secretly re-examined before the third trial. The murder weapon was also re-examined. During the trial, Byron once again claimed the gun was stolen and complained of his current health issues (he was 73 at this time) as an excuse for why he shouldn't be back in court. The trial was held in the same court that the first two were held.

However, his arguments would fail and no all-white jury could save him. This time, a jury split evenly, with eight Black people and four white people, convicted him of murder. He was sentenced to life in prison.

In his closing argument, Assistant District Attorney Bobby DeLaughter stated of Medgar,″What he did was have the gall, the 'uppityness,' to want for his people - what? To be called by a name instead of ‘Boy?’ ... To go into a restaurant? To go into a department store, to vote, and for your children to get a decent education in a decent school?″

Byron would die 7 years later, in 2001, at the Mississippi Medical Center. He was moved from prison to the medical center just hours before he passed away.

Byron spent three decades walking around as a free man, boasting about a murder that he thought he got away with. And in a way, he almost did. He wasn't convicted until he was in his 70s, meaning he lived the majority of his life as a white supremacist free to go about his business until the early 90s.

Medgar Evers legacy will never be forgotten though. He was buried with full military honors in front of more than 3,000 people at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1963, Medgar was awarded the NAACP's Spingarn Medal, the highest honor. Bob Dylan would write the famous song "Only a Pawn in Their Game" in response to the murder.

Medgar showed us that even in the face of adversity, we must continue to fight on. Although he knew he was placing himself in harm's way, he never stopped fighting for equality and equity.

Make sure to head right here for more of BuzzFeed's Black History Month coverage.

money

money