COVID Monoclonal Antibody Therapy: Everything You Need To Know

When we think of targeting COVID-19, vaccines and face masks are the first line of defense. But if you happen to get or be exposed to the coronavirus and you are at high risk of severe disease, there is an overlooked medicine that can help: monoclonal antibodies.

For people who are at high risk of getting severe COVID, “the game isn’t over. There is still this back-up plan available that can help them to better protect themselves from the virus,” said Deborah Fuller, a microbiologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine who is working on coronavirus vaccines.

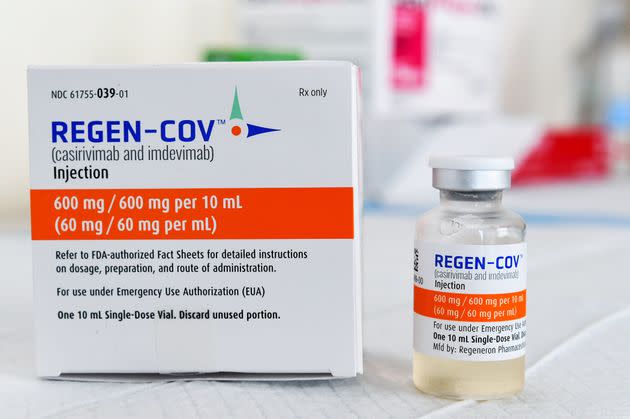

Monoclonal antibody treatments are infusions of lab-made proteins that mimic the immune system’s ability to fight off COVID. Although the Food and Drug Administration gave these treatments — like Regeneron — emergency use authorization in 2020, the criteria for who is eligible to receive them has expanded.

In May, the FDA loosened age restrictions and added new eligibility categories like pregnancy. In August, people who have “post-exposure prophylaxis” ― meaning they were exposed to COVID and are at high risk of getting severe COVID ― became eligible to receive Regeneron. In September, pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly’s monoclonal antibody cocktail also got approved by the FDA as a preventative treatment for people who were exposed to COVID and are at high risk for severe disease.

Millions of Americans are now eligible to receive this COVID therapy that can make a dramatic positive difference for patients, but a lot of people remain unaware of it.

“Most people that test positive for symptomatic COVID-19 are actually eligible for this treatment because they have one or more risk factors for severe disease, but the vast majority of them do not even know about this treatment,” said Adit Ginde, an epidemiologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and an emergency department physician at UCHealth, a Colorado-based health system.

Here’s everything you need to know about what the treatment can and cannot do, and the critical difference between getting a treatment and getting a vaccine.

What exactly is in a monoclonal antibody treatment and how do they work?

In the United States, there are three monoclonal antibody treatments with FDA emergency use authorization for the treatment of COVID-19: bamlanivimab plus etesevimab, developed by Eli Lilly; casirivimab plus imdevimab, made by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and sotrovimab, which is manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline.

In November, the main treatment in use in America was Regeneron’s antibody cocktail, which is what former President Donald Trump got when he was hospitalized with COVID-19 in October 2020. Regeneron’s and Eli Lilly’s drugs are both effective against the delta variant, but in December, Regeneron said its antibodies had “diminished potency” against the omicron variant. Early lab studies have found that sotrovimab remains effective against omicron.

After entering your body, monoclonal antibodies find and bind to the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19. Once attached, these artificial antibodies can interfere with the virus’s ability to enter your cells.

To get the treatment administered, you’ll get antibodies either by four subcutaneous injections in areas like your arms and belly in quick succession, or the treatment will be given to you through a vein intravenously that can take between 20 minutes to an hour or longer. You will then be observed by a health care provider for at least an hour for side effects.

While subcutaneous injections can feel less invasive, “intravenous delivery of monoclonal antibodies [is] by far the most efficient way to get monoclonal antibodies in your body very quickly,” Fuller said.

That’s why in severe situations, providers are more likely to go the IV route because “they are going to want to pump that directly into your veins to get it distributed through your body much more quickly,” she said.

Who is eligible for monoclonal antibody treatment?

If you believe you are at high risk for progression of severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death, you may be eligible for the the COVID-19 antibody cocktails.

Under the FDA’s emergency use authorization, those conditions include:

Being above 65 years of age

Obesity or being overweight

Pregnancy

Chronic kidney disease

Diabetes

Immunosuppressive disease or immunosuppressive treatment

Cardiovascular disease

Chronic lung diseases

Sickle cell disease

Neurodevelopmental disorders such as cerebral palsy

Having a medical-related technological dependence such as tracheostomy or gastrostomy

Factors like race or ethnicity that could place people at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19

If you are in one of these high-risk categories, you can get monoclonal antibody treatment even if you’re fully vaccinated.

Additionally, you could be eligible to get it as a preventative treatment if you are at high risk of getting severe COVID and you have been exposed to COVID.

How effective is it?

Ginde said it can be a life-saving treatment when administered in time. Numerous trials have shown that the treatment can be effective at reducing the risk of hospitalization and death for people at risk of severe COVID.

“Patients feel very sick, they feel like they are really struggling to breathe ... [Then] they get this treatment,” he said. “You’ll hear not infrequently reports of people that are that sick ― that within even six to 12 hours ― feeling like they’ve taken a dramatic turn to the better.”

One study on Regeneron’s antibody cocktail (that has not been peer-reviewed) found that it shortened COVID symptoms by four days and more rapidly reduced viral load compared to people who got a placebo.

Taking the monoclonal antibodies can also reduce the chance of spreading COVID to the rest of the people living in close contact with you. One study showed that it reduced the risk of getting a symptomatic infection from someone in your household who has COVID by 81%.

When do I need to get the treatment in order for it to work?

The monoclonal antibody treatments are meant for mild to moderate COVID cases in adults and children over 12 to prevent the progression of severe COVID.

“The earlier, the better,” Ginde said. “Once you are hospitalized, it’s too late.”

There is a 10-day window to get the treatment after symptom onset, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. If you wait longer, “by then the virus has ravaged the body. And there’s not a whole lot the infusion of monoclonal antibodies is going to do to be able to reverse the course of the disease,” Fuller said. As soon as you know you have been exposed to or have COVID-19, if you are in a high-risk group, you should get it.

How can I get a monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19?

The ease of access varies state by state, as the Department of Health and Human Services determines how much of the national supply gets distributed on a weekly basis. Then, different state and territorial health departments decide which areas receive it and how much.

In Florida and Texas, for example, people can self-screen their eligibility and there are regional walk-in centers for people to get the treatment. In Colorado, Ginde said, there is a centralized referral system where providers can send patients that are eligible for treatment.

The Department of Health and Human Services maintains a national database of where you can access to the treatments.

“Part of it is demonstrating demand as well, the more people ― the community, the public, the providers that really want this treatment ― the more that will help move the needle on expanding access,” Ginde said.

Are there side effects?

It’s rare but possible to have side effects. At least 1% of subjects receiving Regeneron’s antibody cocktail in a Phase 3 trial got skin redness and itchiness at the injection site, according to the FDA.

Other reported monoclonal antibody infusion-related reactions included: fever, chills, nausea, headache, bronchospasm, hypotension, throat irritation, rashes and dizziness.

How much does it cost?

The federal government is covering the cost of the monoclonal antibody therapies, so it is free to get, but there might be an administration cost billed to your insurance if you have one.

How is the treatment different than getting the COVID-19 vaccine?

Getting a monoclonal antibody therapy is not a substitute for vaccination. Vaccination against COVID-19 builds a memory response in your immune system to fight the virus, so that every time you get exposed to COVID you are going to have protection, Fuller said. Meanwhile, the monoclonal antibody therapy builds no memory and “protects you for that moment but then it goes away,” she said.

Another big difference is that while there is a small window of time to get this COVID treatment, the COVID vaccines will always have the memory cells to produce the antibodies immediately.

“Vaccines are so much better because they are there waiting and ready to shut down the virus before it can even get going, whereas with monoclonal antibodies, you don’t take those until the virus has a head start and you are going to have to chase it,” Fuller said.

Could you get antibody treatment more than once?

While COVID-19 vaccines give you lasting protection, a monoclonal antibody infusion “is really maybe good only once or twice,” Fuller said. “You cannot rely on it repeatedly to protect you from COVID.”

If you get it more than once, “your body is going to respond to that therapy differently than it did the first time because it has seen it before,” Fuller said. “It’s going to potentially dampen its potency, you may potentially develop an immune response against that first infusion.”

Why do you have to wait 90 days after receiving monoclonal antibodies to get a COVID-19 vaccine?

Because a monoclonal antibody treatment may interfere with a vaccine-induced immune response, the CDC recommends waiting at least 90 days before getting a COVID vaccine after you receive treatment.

But don’t expect to have the protection of monoclonal antibodies for those full 90 days in your body.

“At some point, it does hit a threshold where you would not be protected, and it’s a very short window of time ― weeks,” Fuller said, noting that every body is different but in about two to three weeks, the amount of monoclonal antibodies circulating in you can dip down to a level that would allow a COVID-19 infection.

“That’s in contrast of course with vaccines where you get a much more sustained level of antibodies,” she said.

Experts are still learning about COVID-19. The information in this story is what was known or available as of publication, but guidance can change as scientists discover more about the virus. Please check the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the most updated recommendations.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.

money

money