This company's permissive policies are behind high-profile police shootings of Black men in the US

The North Carolina sheriff's deputies who fatally shot Andrew Brown Jr. in April could have avoided taking his life, policing experts say, if they had followed best practices and not opened fire when he fled in a car as they tried to serve warrants.

But the fatal shooting may well have complied with the Pasquotank County Sheriff's Office use-of-force policy, which allows deputies to shoot at a moving vehicle even when best practices say they shouldn't.

That's by design. But the policy wasn't designed by the Sheriff's Office, the county commission or any other government authority.

The Sheriff's Office obtained its use-of-force policy from a company that sells ready-to-use manuals that prioritize law enforcement officers' discretion — policies that hold them to a minimum standard that's defensible in court rather than best practices in policing.

The Texas-based company, Lexipol LLC, markets its policies as a way to protect local governments from frivolous lawsuits. That message has attracted clients all over the country, making Lexipol an influential player in the world of law enforcement.

Lexipol says its policies set appropriate standards for officers while taking into account the challenges of making split-second decisions. Policing experts and civil rights advocates say the company’s guidelines — and the willingness of some agencies to embrace them with little or no alteration — has contributed to a heavy-handed approach that has disproportionately cost the lives of Black men.

They cite Brown’s fatal encounter with police as an example.

Brown, 42, was shot April 21 in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, as he tried to drive away from deputies serving him with drug-related warrants. His car bumper passed close to a deputy, who put his hand on the car to jump out of the way. That's when the first shot rang out.

Within seconds, deputies fired 13 more shots as Brown sped across a grassy lot. An autopsy commissioned by the family determined Brown was hit five times, including a fatal shot to the back of his head.

The car stopped in a neighboring yard after striking a tree. No weapons were found on Brown or in his vehicle.

The Sheriff's Office policy says deputies should shoot at a moving vehicle only if they "reasonably" believe there's no other way to avoid an "imminent threat" to deputies or the public. It defines "imminent" as "impending," not immediate.

The local district attorney said the shooting was justified. Scott Greenwood, a prominent constitutional law attorney, said that shows the shortcomings of the department's policy.

"It's a weak policy, it’s a permissive policy; it doesn’t impose any types of restrictions on officers' use of deadly force beyond the bare, constitutional minimum," Greenwood said.

"As a result, it’s quite easy to justify the use of deadly force in circumstances that most practitioners, most police leaders, would tell you would not merit a use of deadly force," he said.

Lexipol declined to provide a company representative for an interview and did not respond to written questions submitted at its request.

The company's policies are full of qualifiers and hedges, a trademark of sorts for the private equity-owned company, which says it works with 8,100 public safety agencies and municipalities in at least 35 states. It's the country's largest purveyor of law enforcement policies.

Founded in 2003 and based in the Dallas suburb of Frisco, Lexipol has filled a vacuum from the lack of national policing standards. It caters to small and midsize departments that make up the vast majority of the roughly 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S.

The company promises to keep them up to date with evolving standards and case law. Critics say its policies are vague and permissive, and departments are unlikely to customize them for the same reason they turned to Lexipol in the first place: Policymaking is time-consuming and expensive.

Lexipol's website is loaded with arguments against best practices advocated by policing experts, such as mandating de-escalation, banning shooting at moving vehicles, and limiting officers' discretion.

For example, the company says officers can't always de-escalate situations because subjects may show signs of "excited delirium" — a condition in which someone displays aggression and apparent immunity to pain, often tied to drug use and mental illness.

Those arguments are contradicted by experts. The American Psychiatric Association says excited delirium is a vague condition disproportionately used to justify harming Black men in police custody.

Ingrid Eagly, a professor at UCLA School of Law who co-wrote a paper on Lexipol for the Texas Law Review, concluded the company structures its policies in a way that's "designed to give maximum discretion to law enforcement officers."

Lexipol clients have included police departments in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, where Daunte Wright was killed this year, and Pasadena, California, where Anthony McClain was killed in 2020. St. Anthony, Minnesota, adopted Lexipol after Philando Castile was killed in 2016. Sacramento, California, did the same after Stephon Clark was killed in 2018. All were Black men.

Lexipol charges public safety agencies annual fees on a sliding scale depending on their size. Often the purchase is subsidized by municipal risk pools.

The company has become a one-stop shop for law enforcement agencies, providing online training, grant assistance, legal analyses, webinars and media through sites like Police One, whose articles are cited by expert witnesses.

Bruce Praet, one of the founders, is a defense attorney who frequently represents officers and departments that have been sued, many of which have Lexipol policies. Co-founder Gordon Graham is an attorney and portrays himself as a risk-management guru. Both are former California cops.

The company regularly partners with the Force Science Institute, whose founder, psychologist Bill Lewinski, is viewed by many policing experts as biased toward police. An editor for the American Psychology Journal called his work "pseudoscience." The Justice Department said it's unreliable.

An independent law enforcement expert who reviewed Brown's death for the Pasquotank County sheriff cited Lexipol and Force Science Institute language, concluding that the use of deadly force "was in direct response to the imminent threat of serious physical harm to persons caused by Mr. Brown’s wanton and reckless operation of his motor vehicle.”

Sheriff Tommy Wooten did not respond to requests for comment.

"There's a growing public demand for police departments to use less force and to use less pain compliance," Greenwood said. "A use-of-force policy that you get from a vendor that allows you to go ... right up to the absolute limit of what you can get away with constitutionally is completely inconsistent with the growing public sentiment."

‘Nothing in police work is black and white’

In 2016, the influential Washington, D.C.-based Police Executive Research Forum urged law enforcement agencies to raise their use-of-force standards above the constitutional minimum.

The litmus test established by case law is that proper use of force is based on whether a reasonable officer would have done the same thing in the same circumstance, with the same knowledge.

The group's stricter guidance was fought by the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the Fraternal Order of Police, which represents 356,000 law enforcement officers across the country.

Lexipol was on their side. In a series of articles published on its site, the company criticized the forum's report, saying its guidelines sacrificed officer safety and overemphasized the "sanctity of life."

A year later, law enforcement groups put out a "National Consensus Policy on Use of Force" recommending, among other things, that agencies mandate de-escalation tactics and avoid shooting at moving vehicles.

Again, Lexipol pushed back. Calling de-escalation "the latest buzzword," Praet wrote that "agencies must exercise extreme caution" when mandating what officers should do.

In a webinar after the 2019 passage of a California law mandating a higher standard for deadly force, Praet said, "One of our secret sauces, so to speak, is that rarely, if ever, will you see the use of the word 'shall' in our policies because nothing in police work is black and white."

Praet encourages liberal use of the word "reasonably" in policies – as in "reasonably appears necessary" or "reasonably believes." But that makes for murky guidance.

"If there’s any kind of room for extenuating circumstances, officers interpret that as, well, this could be an extenuating circumstance," said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum. "You need to be clear and unambiguous. What these other policies do is allow some kind of wiggle room."

Lexipol staff often use edge cases to make their points. At a May conference, program manager Mike Ranalli, retired chief of the Glenville, New York, police department, discussed shooting at a moving vehicle. He showed a video of officers on foot trying to stop a car in the snow. One of the officers falls and slides in front of the fleeing vehicle. Ranalli said the situation showed why officers may need to fire at a moving vehicle.

That's not a typical situation, Wexler said. Most cases in which officers shoot at a moving car involve those who place themselves in danger, such as by moving in front of a fleeing vehicle, he said.

The New York Police Department has banned shooting at moving vehicles for nearly 50 years –– as long as the threat is solely from the vehicle. That move led to an immediate, sharp reduction in uses of lethal force, Wexler said. Other major police departments have followed suit.

Co-opting the language of reform

Windsor, Virginia, drew national attention after video showed U.S. Army Lt. Caron Nazario being pulled over in uniform by two police officers in December and ordered out of his SUV at gunpoint. With his hands up, the Black and Latino soldier was pepper-sprayed in the face.

In an effort to improve policing and regain community confidence, Windsor Police Chief Rodney Riddle pushed the town's council to outsource the department's policies, training and enforcement strategies to Lexipol.

Officials hoped to use federal coronavirus stimulus funding to pay the roughly $25,000 fee.

Lexipol policies have been implemented in departments facing civil rights investigations, such as New Orleans; Newark, New Jersey; and Oakland, California. More recently, its policies have appeared in departments seeking to reform themselves.

"Everything about the (Lexipol) policies is the exact opposite of what people marched in the streets to secure," said Carl Takei, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU who focuses on police practices. "But Lexipol is very creative at finding new ways to make a buck off of the policies that they sell. And one way is to co-opt the language of reform."

Some of New York's more than 500 law enforcement agencies turned to Lexipol after the governor ordered them to modernize policing based on community input or lose state funding.

"Most agencies don’t have the capacity to keep their policy manuals up to date," said Jim Bueermann, a retired Redlands, California, police chief and former National Police Foundation president. He sits on Lexipol's Law Enforcement Advisory Council.

The smaller the department, the older its policy manual likely is, he said. At one time, his department's manual was 15 years old.

In Minnesota, where lawmakers banned chokeholds after George Floyd was murdered by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, there was discussion of legislation requiring law enforcement agencies to use Lexipol.

Bill Bolt, the police chief for the town of Minneota, wrote his state representative asking him not to move forward. Minnesota is so diverse that a statewide policy would never meet every community's needs, Bolt wrote.

Bolt said that while Lexipol told him he could change its policies to fit his needs, it made him wonder: "Why would I need to get rid of of my current policy and adopt another which I would end up changing so significantly that it would not be in line with the original Lexipol policy."

No time for community input

Berkeley, California, known for its liberal activism, has prided itself on strong civilian oversight of its police department, the result of years of community outreach.

That stopped once the Berkeley Police Department adopted Lexipol's policies, said Andrea Prichett, the founder of Berkeley Copwatch. She resigned from the city's Police Review Commission, an independent civilian oversight agency, in 2018.

A Berkeley resident for more than 35 years, Prichett said she saw decades of community input disappear, replaced with policies all "about liability and not about what's best for our community."

When the department adopted Lexipol, it "would give us batches of 20 policies at a time," she said. "The police chief said, 'We’re going to release these policies; you better hurry up if you want to comment on it. We spent a lot of money on this.'"

Prichett said it was impossible to digest the policies and solicit public input so quickly. Eventually the commission created a committee, which included lawyers, that spent hundreds of hours going through the policies, she said.

In an emailed statement, department spokesman Officer Byron White said "most existing policies were simply converted into Lexipol policy format with no substantive changes."

The department isn't required to receive approval from the commission for its policies, White said, but it allowed "ample time to review and engage with the community."

The commission still hasn't reviewed 50 of some 200 policies provided nearly three years ago, he said.

Policies become embedded in an agency's culture when they are homegrown, said Greenwood, who frequently reviews them for police departments.

"I've had command-level personnel in some agencies tell me very bluntly before that they pay no attention to the policy book because it's not theirs," Greenwood said. "They refer to it as the Lexipol manual."

Still, Lexipol's templated approach has created much-needed consistency among the nation's law enforcement agencies, Bueermann said.

"It's not a perfect system," he said. "You buy the core concepts, then you have to decide if that’s going to work in your city or not."

Upping the legal bar for deadly force

In California, where the company got its start, Lexipol policies have been used by about 95% of public safety agencies.

In 2019, the company worked behind the scenes with a law enforcement lobbying group to weaken legislation that upped the standard for deadly force from "reasonable" to "necessary."

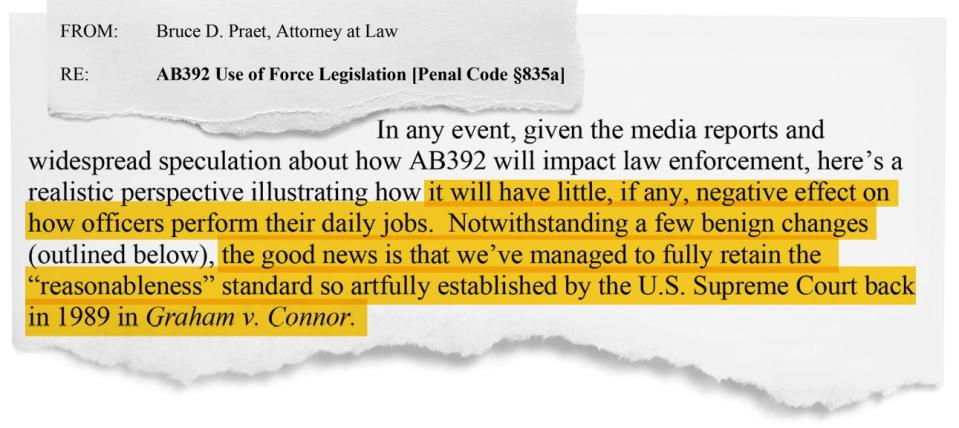

In a 2019 webinar, Lexipol's Praet told clients that, contrary to media reports, the legislation had changed nothing.

The final language of the California Act to Save Lives removed a requirement that officers de-escalate situations. It stripped out the definition of "necessary," which said an officer needed to "conclude that there was no reasonable alternative to the use of deadly force" that would keep someone from being hurt or killed.

"The good news is, they didn't get 'necessary.' We stuck with reasonableness," Praet said in the webinar. "If it had gone 'necessary,' my advice to you would have been (to) retire because you couldn't have done police work anymore."

He continued, "What is the new standard? The new standard is the exact same thing we've had for the last 50 years, and that is the Graham vs. Connor objective reasonableness standard."

After the law was changed, the Peace Officer Research Association of California, the state's largest law enforcement organization and lobbying arm, provided its members with a link to a "legal analysis" on the new law, written by Praet.

Without a definition for "necessary," it will be up to courts to interpret the law, said Samuel Sinyangwe, co-founder of Campaign Zero, a national nonprofit focused on ending police violence.

For now, he said, "the only people who are defining this are the people writing the policy for the police departments, which is Lexipol."

Tuesday, the ACLU of Southern California, the League of Women Voters of California and 23 other organizations sent Lexipol a letter about its "inaccurate instruction" of the state's new standard for deadly force.

They said Lexipol confuses the different standards for force by sprinkling "reasonableness" throughout its policies, even though California law now says deadly force must be necessary.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

They urged the company to adopt clearer language that tells officers to use the "minimal force necessary."

Agencies say they trust Lexipol, said Ashley Raveche, deputy director for social policy for the League of Women Voters of California.

"Folks are being penny-wise and pound-foolish," she said. "They’re relying on Lexipol because it’s cheap, it's easy."

The ACLU has sued the Pomona Police Department for using Lexipol policies and training that conflict with the new law. Its officers have been involved in multiple fatal shootings since the law went into effect last year.

A killing in Pasadena

Pasadena's Police Chief John Perez politely rebuffed the League of Women Voters when he received a letter raising questions about the department's use-of-force policy, said Kris Ockershauser, a longtime Pasadena-area activist and a leader of the local chapter.

Then Floyd was killed. The city revised its policy over the summer to align with state law.

"We police with the consent of our communities, so we have to make sure it fits," Perez said in an interview. He said Lexipol brings many benefits: It saves time and money, emails departments about policy updates and offers online training.

Less than a month after the department updated the policy, a Pasadena police officer fatally shot 32-year-old McClain, a Black man, as he ran away after a traffic stop.

The League of Women Voters and civil liberties groups questioned whether officers properly followed the revised policy.

The Los Angeles County DA's office is reviewing the officer's conduct, a spokesman said. The family, represented by civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump, has filed a federal lawsuit.

The officer who shot Brown is back on duty after mandatory paid leave to get counseling, a requirement of any officer involved in a serious incident, said Pasadena spokeswoman Lisa Derderian. Due to the lawsuit she declined to provide details on the incident.

Officers "don't need to be attorneys" to do their jobs, Raveche said. "They need clear directives on how to do their job."

USA TODAY national correspondent Tami Abdollah covers inequities in the criminal justice system. Send story tips by DM @latams or tami(at)usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Use of force policies written by Lexipol at play in police shootings

money

money