How the Brooklyn Bridge went from being a 'wild experiment' in architecture to becoming designated a historical landmark 140 years later

The history of the Brooklyn Bridge is filled with death, disease, and controversy.

The main architect died before the bridge was even built, and several workers died in the process.

Tools and techniques used to build the bridge — then thought to be a "wild experiment" — are commonly used today.

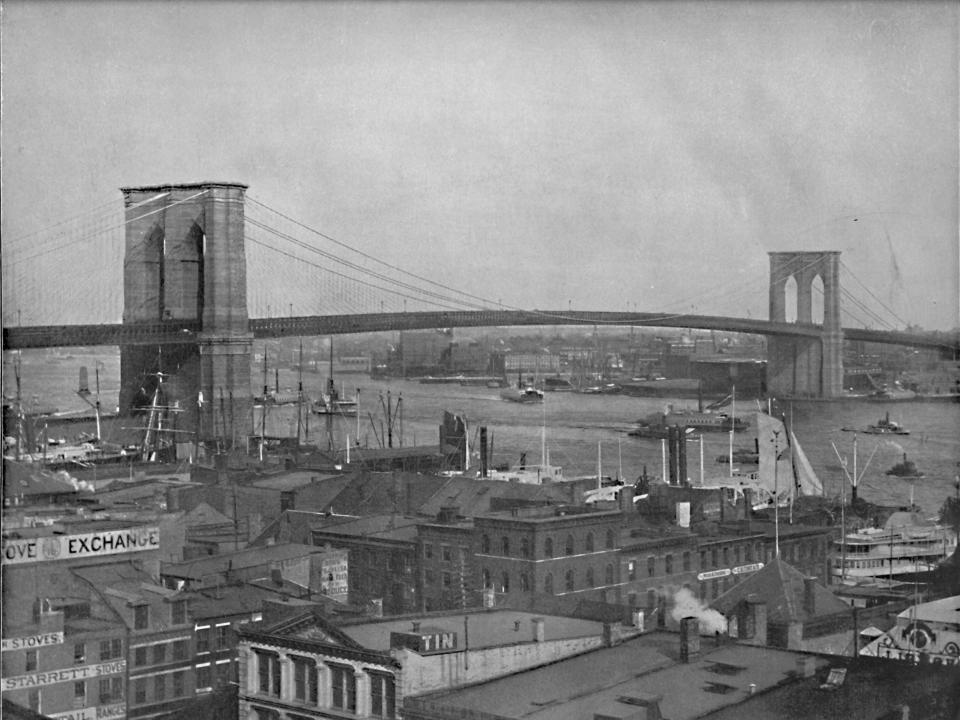

The Brooklyn Bridge, one of New York City's famous landmarks, turned 140 this year, and its history has been wrought with death, disease, and controversy.

During the bridge's construction, over a dozen people died, while countless others were bedridden with a then mysterious illness, including the bridge's architect Washington Roebling.

Most deaths involved with the Brooklyn Bridge happened during its construction, except for Roebling's father, John Augustus Roebling, the man behind the bridge's design who died from an illness weeks before construction was supposed to start.

The bridge was made to connect Brooklyn and Manhattan in place of regularly scheduled ferries. It is estimated that over 70 million crossings were made across the river separating the two cities yearly before the construction of the bridge.

But after a crash between two ferries in 1868 injured 20 people and killed a young boy, public support for the bridge to be built was on the rise, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Washington Roebling took up the task of completing what was the longest bridge in the world at the time, and he had to do it with only the notes left by his late father. If the bridge were a success, the world would remember the Roeblings' ingenuity and engineering prowess. But if it failed, the sole responsibility would be put on him.

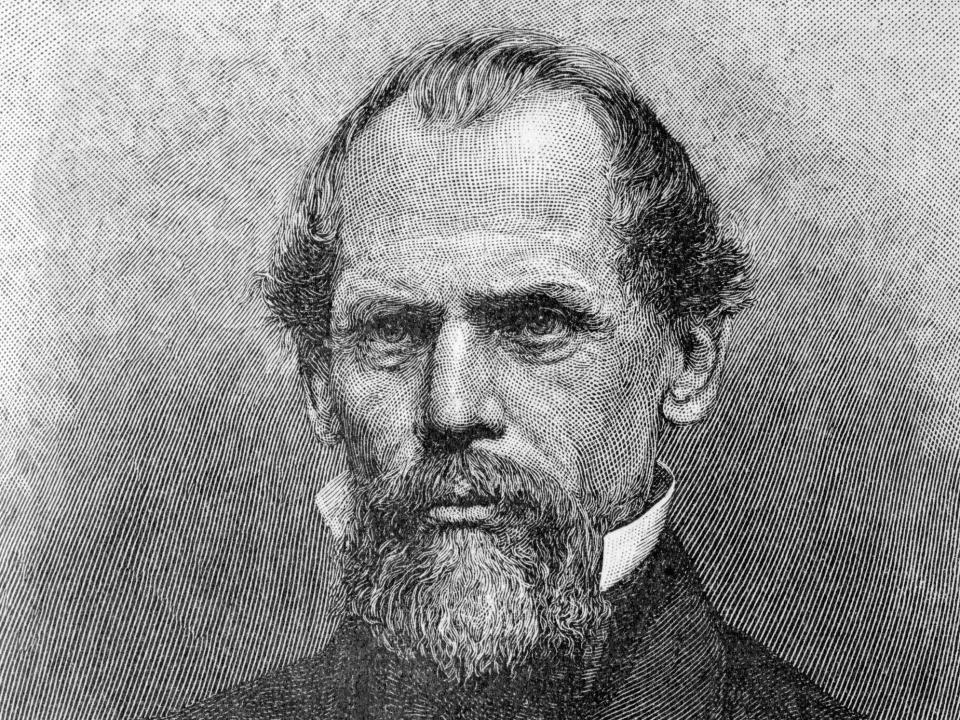

John A. Roebling was a German immigrant who became a brilliant and important architect for the United States.

Roebling was a prolific engineer pioneering new techniques that eventually led him to design the suspension bridge.

Roebling noticed that the hemp rope companies used to move train cars was susceptible to frays and tears and had a better idea. Instead of using hemp rope, why not use more durable iron cables?

Roebling began working on prototypes of iron cables wound together that he would use on railways. He patented his invention in 1842.

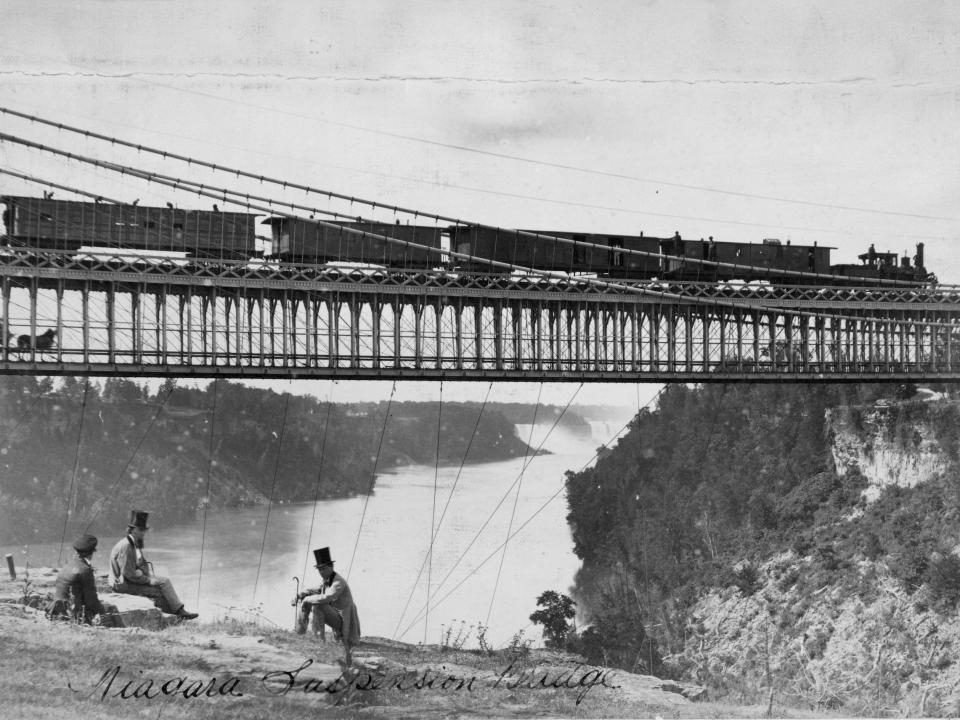

Roebling would take on jobs and build suspension bridges in Ohio and Pennsylvania. He also worked on a bridge over the Niagara River, connecting New York to Ontario. In 1866, he built what was then the longest bridge in the world, the Cincinnati-Covington Bridge.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, American Society of Civil Engineers, Washington Post

His success across the nation eventually led him to his final project: the Brooklyn Bridge.

Roebling began working on plans for the Brooklyn Bridge in 1867. He had planned out the big stone structures and how the cables for the suspension of the bridge would be laid out and connected.

"The completed work, when constructed in accordance with my designs, will not only be the greatest bridge in existence, but it will be the greatest engineering work of the continent, and of the age," Roebling said of his design.

Unfortunately, he would never get to see his dream come true. In June 1869, right after city and federal approval for the bridge passed, Roebling's foot was crushed by a passing ferry while scouting the location for the bridge foundation.

He died of tetanus 24 days later and never saw construction start on the bridge.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History.com, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

John Roebling's son Washington Roebling took over the construction.

Washington studied engineering and went into business with his father, helping him build bridges across America.

After the bridge was completed, Washington Roebling joked that "many people think I died in 1869," implying that he would often get confused for his father, as well as the credit he was due.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

The bridge started construction and was hailed by engineers as a "wild experiment."

It used two new technologies of the era: steel wires and pneumatic caissons.

Sources: American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

One of the biggest anomalies of the bridge was its use of steel cables instead of traditional iron cables.

The practice is widely used today, but the Brooklyn Bridge was the first to attempt it.

Before they built the Brooklyn Bridge, Roebling and his father would use iron wires for their suspension bridges. But because this bridge was significantly larger in size, the iron would make suspension cords too much of a hassle.

Using iron would "necessitate a cable of such weight and size that it would become unmanageable and involve the greatest difficulties in making it," Roebling said.

Sources: American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers, Erica Wagner

Each of the bridge's four main cables of the bridge is comprised of 5,434 continuous steel wires.

The wires for the bridge were provided by a "corrupt manufacturer." He submitted wire that passed initial inspection tests but later provided faulty wire for the rest of the bridge. The scheme went undiscovered for months, and the faulty wires are still a part of the bridge today.

Luckily, the Roeblings built the bridge to be eight times stronger than it needed to be — a nod to the importance and strength of using steel wires.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

Using steel wires later became common practice.

Roebling's steel wire innovation was used on famous bridges like the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

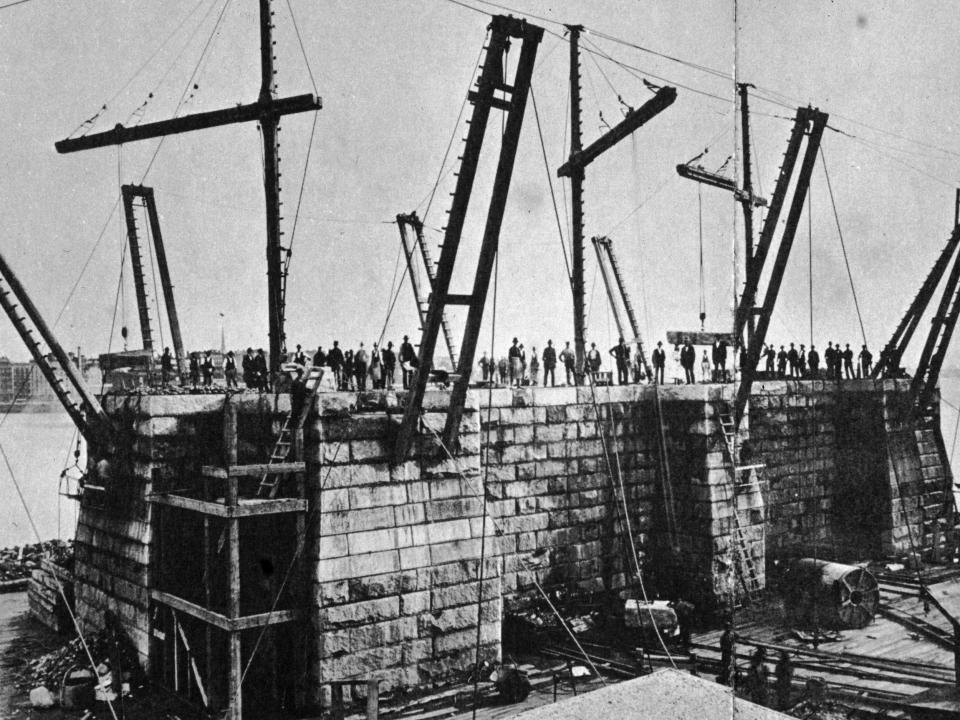

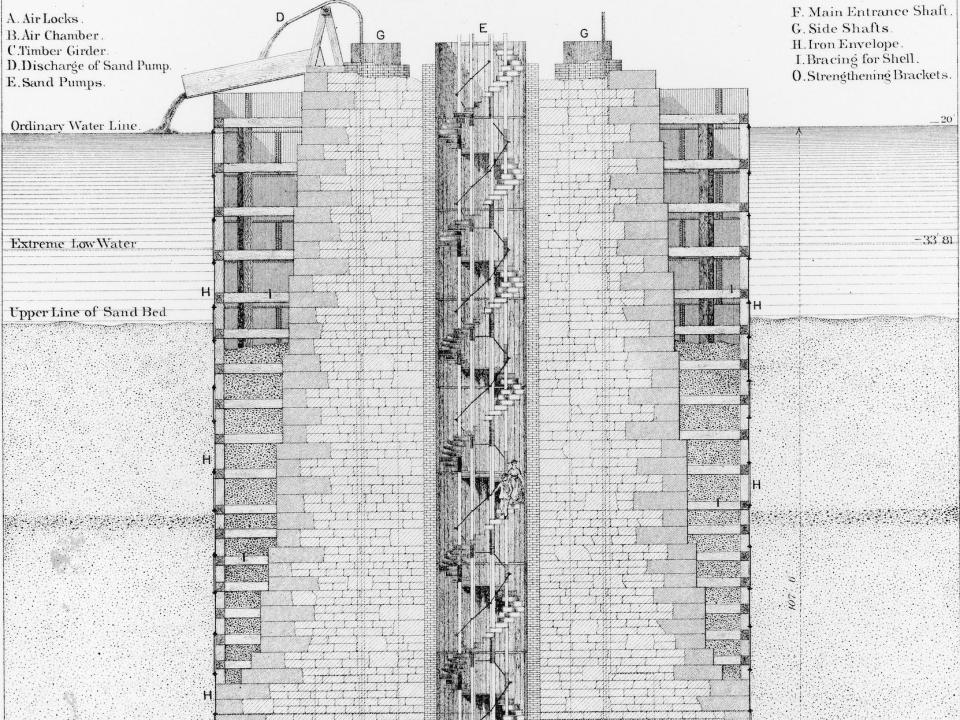

The Brooklyn Bridge was also among the first to use pneumatic caissons.

Caissons are big, watertight structures designed to be the precursor to the foundations of bridges, dams, and ships.

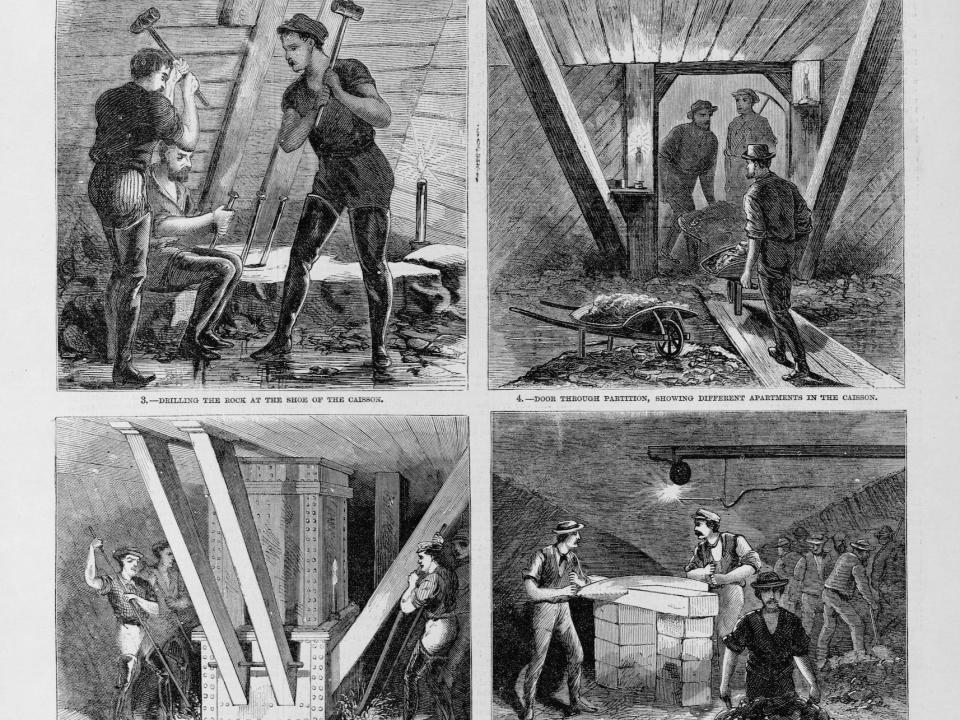

A bottomless structure is put into mud and sediment and then hammered down towards the bedrock. The caisson is pressurized to keep water out and allows construction workers, who were dubbed sandhogs, to shovel out mud, rocks, and sediment to later fill the caisson with concrete.

Using pneumatic caissons was essential to building the Brooklyn Bridge and allowed the workers to essentially work underwater. But using caissons came with a cost as workers started to get sick, including the head architect Washington Roebling.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

Working conditions in the caissons were compared to conditions described in Dante's Inferno with imaginary noises and shadows.

EF Farrington, Roebling's master mechanic, described mysterious sounds, shapes, and shadows being seen and heard throughout the caissons.

The hot, compressed air caused workers to experience headaches, bloody noses, itchy skin, and even slowed heartbeats. Ultimately, it is estimated that 110 workers became ill while working in the caissons, and 14 workers died.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

The mysterious disease was decompression sickness, colloquially known as the bends, which is commonly seen in divers.

Workers would get into an airlock to descend below the water and into the caisson. As they made their descent, the airlock would fill with compressed air which allowed workers to breathe while keeping water out. However, the descent also filled workers' blood with dangerous gasses.

Upon their ascent back to the surface, the blood of the workers would release dangerous gasses. This was the first use of the term caisson disease and the Grecian bend, also "the bends" both now known as decompression sickness.

The bends are characterized by excruciating joint pain, paralysis, convulsions, numbness, speech impediments, and in some cases, death.

Sources: Harvard Medical School, Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

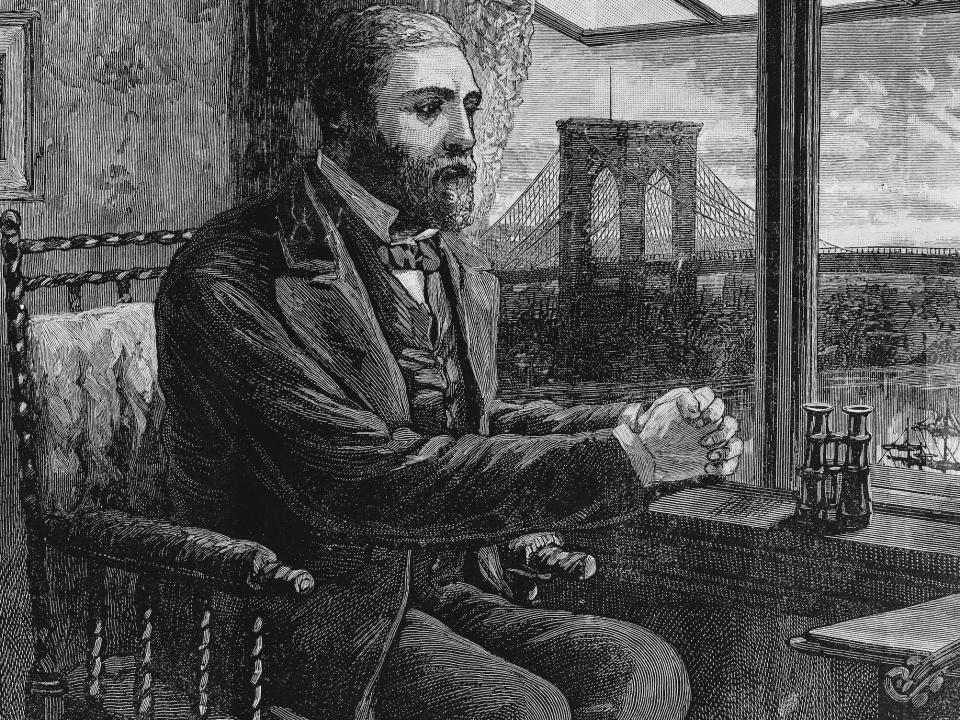

Washington Roebling became paralyzed for the rest of his life from the sickness and watched the opening of the bridge from his bedroom.

As the construction went on Roebling would watch and supervise from his window looking out at the bridge.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

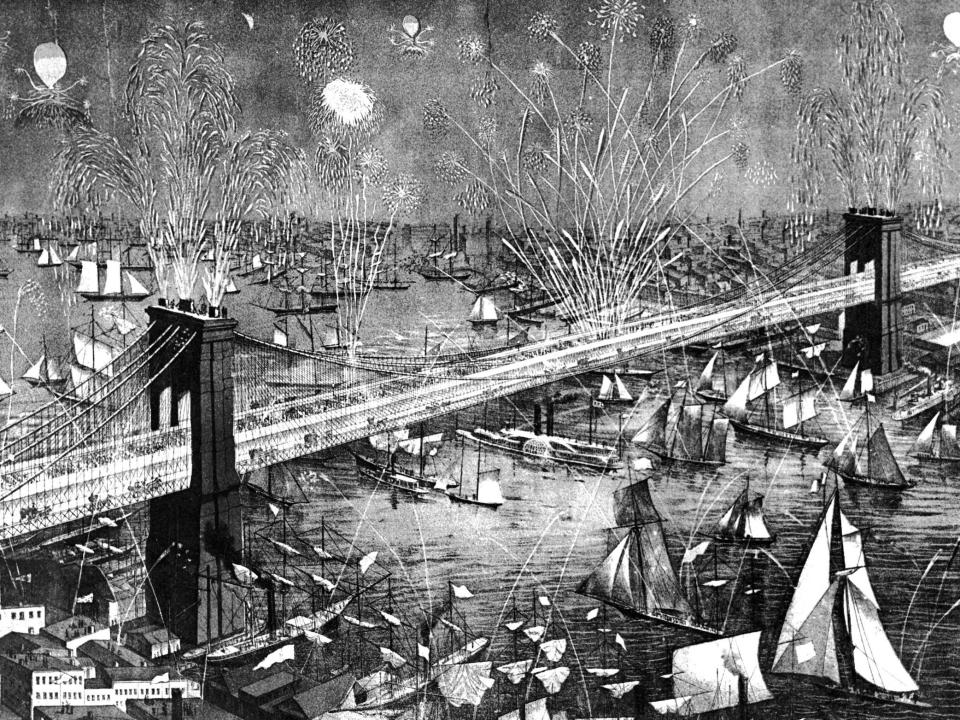

Despite workers being impacted by death and disease, the bridge finished construction in 1883.

Source: Associated Press

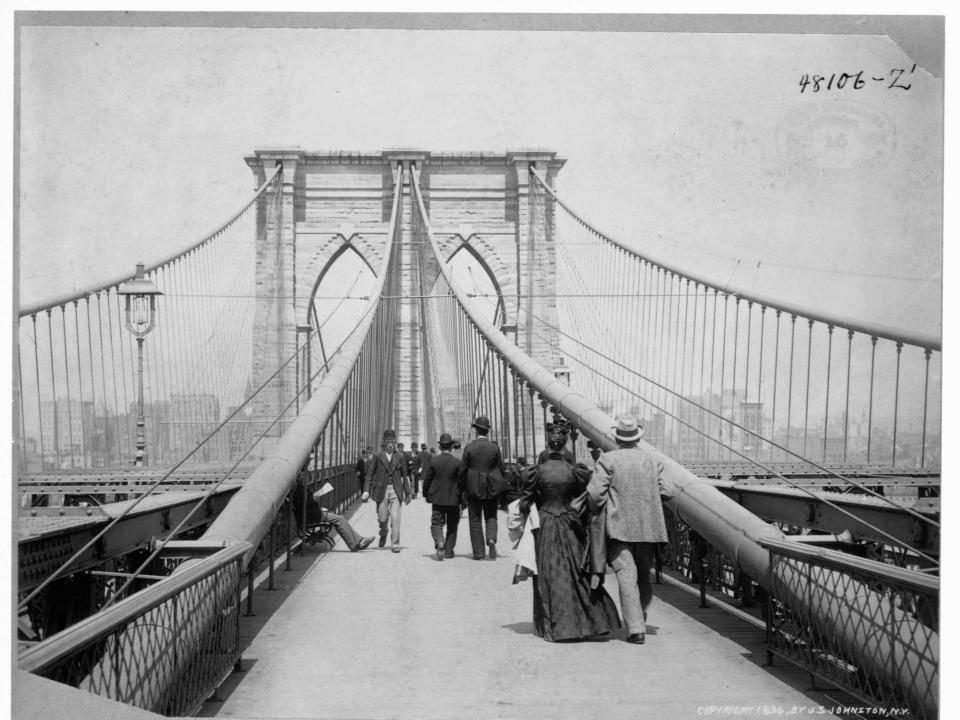

The bridge was completed with an elevated railway and pedestrian walkway.

Roebling thought it was important that people were able to use the bridge and partake in the leisure afforded by it.

In the time since its construction, the Brooklyn Bridge promenade has been used for demonstrations, marches, and as a way to get between Manhattan and Brooklyn during emergencies or transit blackouts.

Sources: Associated Press, Daily Beast, History, Washington Post, American Society of Civil Engineers, American Institute of Steel Engineers

Two decades later, the bridge now carries over 118,000 cars between Manhattan and Brooklyn every day.

Source: New York Department of Transportation

The Brooklyn Bridge became a designated historical landmark in 1964.

The bridge has appeared in countless movies, books, and TV shows since its construction 140 years ago.

Source: New York City Department of Transportation

Read the original article on Business Insider

money

money