Brendan Fraser: ‘I don’t look the way I did – and I don’t necessarily want to’

NB. This interview first ran in February, and has been republished following Brendan Fraser's Best Actor win at the 2023 Oscars

“It’s all right if you need to move that closer,” Brendan Fraser says, pointing at my dictaphone. The 54-year-old star of the Mummy franchise and George of the Jungle might have built his career on swashbuckling raucousness, but these days, vocal cord surgery has left his voice hushed and hoarse.

Dressed in a conservative blue suit, he looks less like a Hollywood star than a candidate in a job interview, and while he remains instantly recognisable, his wide eyes have a new, searching gleam, and his physique has grown from strapping to tree-trunkish. None of us is the same as we were 20 years ago, but Fraser has been out of view for so long – in Hollywood, at least – that middle age feels like a plot twist.

Of course it’s entirely possible you have seen him on the small screen recently: he’s been working fairly steadily, mostly in character roles for TV, since his leading man career came to an abrupt end in the late Noughties. He was in DC Comics series Doom Patrol – although much of his costumed character’s performance was acted by a body double – and he talks animatedly about working with Danny Boyle on Trust, the US drama about the John Paul Getty kidnapping, in which he played the Getty family’s head of security, James Fletcher Chace.

But he hasn’t been seen in British cinemas since 2010 offering Furry Vengeance: a manic children’s film, part-funded by the Abu Dhabi government, in which he played a property developer terrorised by forest wildlife.

It’s fair to say that his comeback role is rather different. At Venice Film Festival in September, Fraser received a six-minute standing ovation for his lead performance in The Whale, a chamber piece from Darren Aronofsky, the director of The Wrestler and Black Swan. The film’s UK premiere in October brought another standing ovation – and yet another at a special screening in London the following night. For a while, it felt as though 50 per cent of social media comprised videos of Fraser standing awkwardly in black tie, against a backdrop of applause. The acclaim, he tells me, is “like nothing I’ve ever previously experienced”.

Not even for his billion-dollar-grossing Mummy trilogy, or his 2006 Best Picture Oscar-winner Crash? “No, those were different altogether,” he objects. “If people were praising them, it was because of the overall… thing.” This time, he continues, “it has been absolutely humbling and affirming – recognition for what Darren has managed to do with me and four other actors in a two-bedroom apartment”.

The Whale began life as a play, written by Samuel D Hunter staged off-Broadway in 2012. It centres on Charlie, a 42-stone recluse trying to reconcile with his estranged teenage daughter (played on screen by Stranger Things star Sadie Sink) – though the seeming cruelty of its title also nods at its literary and scriptural resonances: Moby-Dick and the Book of Jonah, respectively. Aronofsky, a filmmaker not known to shy away from Biblical allegory, saw The Whale on stage that year and immediately joined the bunfight to secure the screen rights.

At one point, an adaptation was to be directed by George Clooney; at another, it was going to Tom Ford, with James Corden attached to play the lead. Aronofsky, however, had always intended to use the film to “reintroduce” an actor. Then he happened to see Fraser in a trailer for a sleazy Brazilian thriller he had made in the mid-Noughties, and during its climactic haunted close-up, something clicked.

Thank goodness it did. Fraser’s performance in The Whale, which has seen him nominated for the Best Actor Bafta and Oscar for the first time in his life, is extraordinary: by turns frightening, warm and achingly sad, it paints Charlie’s junk food addiction as a form of self-harm that has swallowed him alive.

Fraser “had no idea what the film was about” when Aronofsky first asked to meet him. But he quickly recognised that Charlie’s plight refracted elements of his own.

“I could absolutely connect with having to reconcile your physical decline with ongoing feelings of love for your child,” he says. “I’m the father of three sons [with the former actress Afton Smith, whom he divorced in 2007] and I know that I gain a lot of strength from that bond.”

Fraser’s children, now aged between 16 and 20, missed their father’s matinee idol years. Nevertheless, are they aware of them, and are they proud? “I don’t know,” he splutters, suddenly embarrassed. “I’ve never asked them that, or wondered it. But they’ve said, ‘Man, that’s cool,’ which is enough. “I mean,” he flushes, “they’re big, handsome boys. They are the matinee idols now.”

When he thinks of Charlie’s own feelings for his daughter, he explains, “It’s not much of a reach to know what it would be like to find myself in that same fraught place”.

Fraught would certainly be one word to describe the past decade for Fraser, in which his earlier years of action heroism exacted a punishing toll. “I got a little banged up from years of doing my own stunts,” he explains, “and needed a surgical fix on the spine and the hinges.” Within a period of seven years he underwent several drastic surgical procedures, including those vocal cord repairs, a partial knee replacement and a lumbar laminectomy to remove a portion of bone from his lower back. “And that took a lot out of me. I knew I would get better, but it took a long time.”

He says that early in his career he felt uncomfortable with the ease of his stardom and wanted to ensure “those physical performances, whether fighting, dancing or comedy, had an element of self-sacrifice. But it wasn’t very clever of me at all.”

While shooting the third Mummy movie in China in 2007, “every morning I was putting myself together like a gladiator with muscle tape and ice packs, strapping on this Transformer-like exoskeleton just to get through the scene.” Still, he insisted on taking the hits, feeling that those studio pay cheques – in those days up to $10 million per film – had to be earned.

Was there an element of self-loathing at play, too? In 2003, after missing out on the role of Superman in Warner Bros’ forthcoming reboot, Fraser played his own stunt double in Looney Tunes: Back in Action, and insisted that at the end of the film, his character should lamp the “real” Brendan Fraser – a preening, arrogant halfwit, also played by him – square in the face.

“Absolutely there was self-loathing,” he says. “I think on some level I felt I deserved [a beating], and wanted to be the one who got in the first punch.”

His self-image was further crushed by an incident at the Beverly Hills hotel in the summer before Looney Tunes was released. In 2018, Fraser alleged that at a lunch thrown in 2002 by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association – the group behind the Golden Globe awards – the organisation’s former president Philip Berk sexually assaulted him, groping his rear during a conversation. (Berk, who described jokingly pinching Fraser’s bottom at the party in his own 2014 memoir, has since dismissed Fraser’s claim as “a total fabrication”.)

Did that make Fraser feel even more like a side of meat, hanging in the industry window, rather than the serious actor he had dreamed of becoming? “I don’t know if I ever thought of it that way at the time, but it’s a fair question,” Fraser says hesitantly. “I do know that it brought me to a point in my life when I needed to retreat. And I did.

“And I mean, I’m older now; I don’t look the way I did in those days, and I don’t necessarily want to. But I’ve made peace with who I am now. And I’m glad that the work I can do is based in an emotional reality that’s not my own life, but is one that I can strongly identify with.”

Not that it was necessarily obvious from his goofy screen persona in early films such as California Man (in which he played a caveman defrosted in 1990s Los Angeles), but as a performer, the Indiana-born Fraser has always been thoughtful and studious. His father Peter worked for the Canadian tourist board and was based in the Netherlands for a spell: his family often came to London for Christmas, “where I saw The Mousetrap, Jesus Christ Superstar, Oliver! And I was captivated. From that point, I knew I wanted to be part of what they did up on that stage.”

As a student at Seattle’s Cornish College of the Arts, he idolised Ian McKellen, later auditioning for his 1995 filmed production of Richard III. That time, he was unsuccessful – “he sent me a handwritten note saying he didn’t have a place for me, though he could have used some of my much-needed enthusiasm, which was a very generous thing to say”. But three years later the pair starred opposite one another in Gods and Monsters, as the ageing gay filmmaker James Whale and his gardener Clayton, who is handsome, young – and straight.

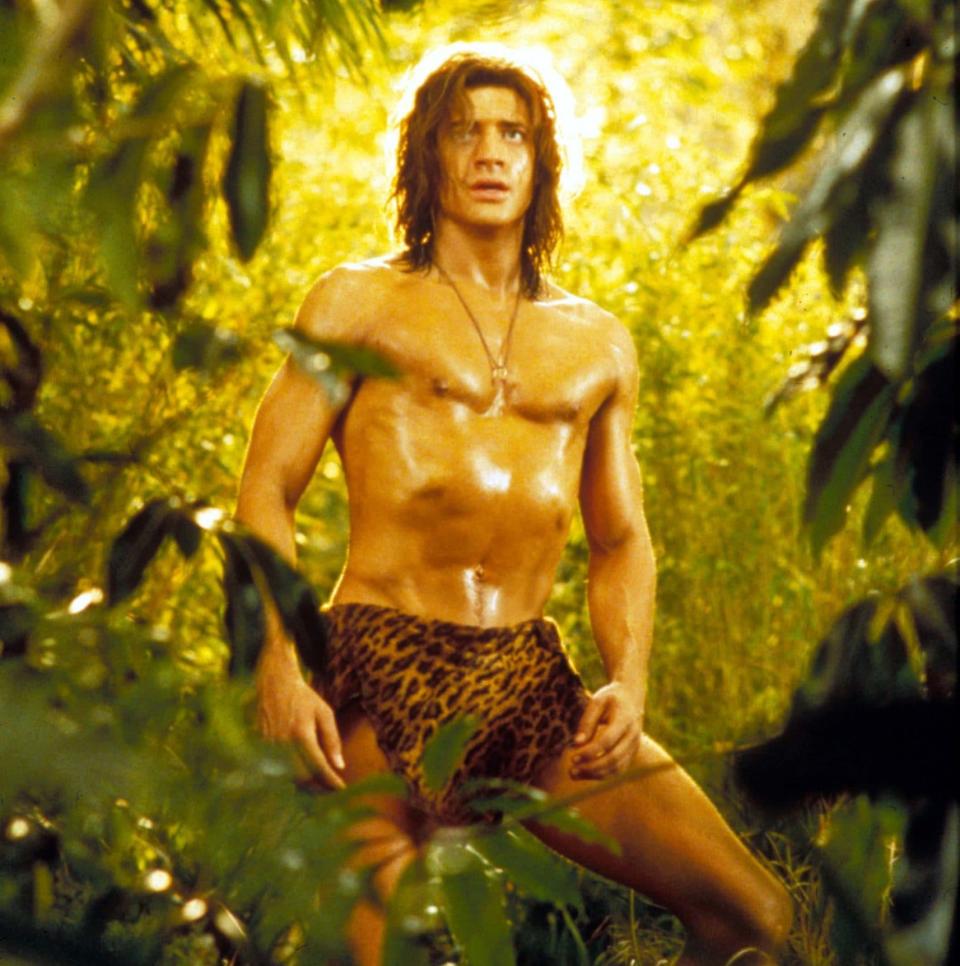

Fraser also obsessively studied the performances of American mime artist Bill Irwin, whose style owed a debt to the great silent comedians. Fraser’s George of the Jungle might have been Baywatch-era beefcake – “It made sense that I had to look like that if all they were giving me to put on was a butt flap,” he concedes – but he saw himself working in the slapstick tradition stretching back to early Hollywood.

He talks about playing Charlie in The Whale in similar terms, as a largely physical undertaking. The design of his 21-stone prosthetics, filled with dried beans to simulate the bob and sag of human flesh, “was all in service of authenticity, not the one-note joke these bodies have been in the past in broad comedies”. The fat suit, he insists, “wasn’t restrictive – I found it helpful, honestly, that it was so cumbersome. I learned that Charlie had to be an incredibly strong man to carry around that body, which I thought was kind of poetic.”

He is aware of the tutting over the film’s mere existence: the gripes that fat suits are necessarily demeaning; the quibbling over his lack of “lived experience” of Charlie’s life-threatening state.

“But it’s books and covers, you know?” he shrugs. “You need to see the work. All I can say is that I knew it had to be done with sensitivity and honesty. Putting quotation marks around Charlie – trying to sentimentalise him, or make him a circus act – would be nothing that I would want to be a part of.”

However the awards season pans out, Fraser has already won. Through the sheer quality of his performance, he is back on everyone’s radar, with a forthcoming role in Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, opposite Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio, and a return to comedy in Brothers, by the Palm Springs director Max Barbakow.

He feels finally able to freely put into practice what he was “taught at school a thousand years ago: to go towards the danger”. He beams. “That’s where the best work happens. You have to take the part that will upset your mum.”

The Whale is in cinemas now

money

money