Boxer's incredibly tragic and unlucky life may have just taken a turn for the better

Life was never really normal for Jerrico Walton. He grew up in one of the poorest sections of New Orleans, living in Section 8 public housing. His father, John Sebastian Holmes, was a notorious drug dealer who was in and out of prison, and rarely played a part in his son’s life.

He was doing well in school — “Straight A’s,” Walton said, proudly — and showed promise as a football player at Landry High School.

He lived with his mother, Gail Walton, his half-brother, Alvin Charlie Walton, and his half-sister, Clarenisha Shagail Walton. He was 14 years old in August 2005 when New Orleans residents were urged by local officials to leave the city because of the impending Hurricane Katrina.

The Walton family chose not to heed the warnings, and they paid a terrible price.

“We didn’t think it would do the kind of damage it would do,” Jerrico said. “We didn’t really know what would happen.”

Finances also played a role, as the family was struggling and couldn’t afford to spend money to travel.

On Aug. 29, 2005, winds began to blow and rain began to pelt the city. Jerrico and Alvin were in the bedroom on the second floor of their apartment. The brothers looked outside and saw the water already at the window.

“It was just crazy, man,” Jerrico said.

Soon enough, all hell broke loose as Katrina unleashed its wrath on the city. The levees broke and a storm of epic proportions washed over New Orleans. When it was over, the damage it caused exceeded $160 billion. More than 1,800 people died. Tens of thousands more were displaced from their homes, among them Gail, Jerrico, Alvin and Clarenisha Walton.

At first, they stayed in a shelter. Soon, they traveled to Lafayette, Louisiana, where they stayed free in a hotel provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. After a while there, they decided to make the four-hour drive to Beaumont, Texas, where they would live with relatives.

That turned out to be a fateful decision.

Not long after they arrived in Beaumont, Hurricane Rita hit. Though it wasn’t nearly as destructive as Katrina, it killed seven people, caused more than $23.7 billion in damage and displaced countless more people.

Among those were the Walton family.

Managers worry if Walton’s past will catch up to him

Jerrico Walton is now 29, a promising professional boxer unbeaten in 16 pro fights with seven knockouts after an abbreviated seven-bout amateur career. On Friday, he’ll face Montana Love in Philadelphia on Showtime’s “ShoBox: The New Generation” in the biggest fight of his career.

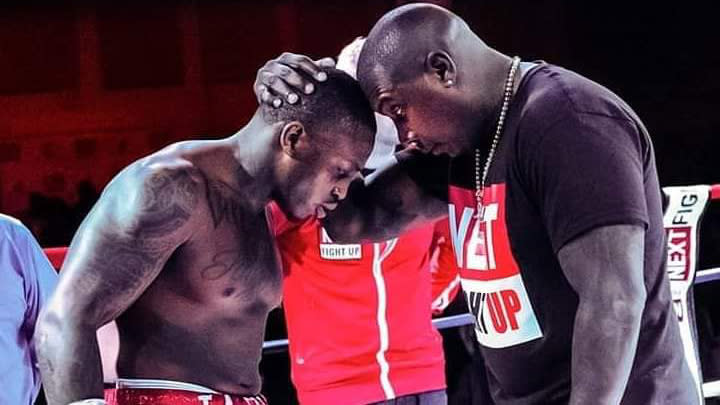

His trainer, Ronnie Shields, is high on his potential and believes he can be a world champion. Walton has only worked with Shields for four fights. Prior to that, he was wild and didn’t have much structure in his approach. Shields wants him to be aggressive while working behind a jab and not just turning a bout into a brawl.

“He’s got a lot of talent and he’s no question good enough [to win a world title],” Shields said. “He has this style where he can put a lot of pressure on, but he can box also. He likes to counter punch, but I’d like to see him be more aggressive. He’s a good puncher. When he sits down on his shots and lets them go, he can bang.”

The question that keeps his co-managers, Forris Washington, Joseph Vredevelt and Mike James, up is whether his past will catch up to him before he fulfills his potential.

Walton has been through more in 29 short years than 10 people are in a full lifetime.

“He’s an incredibly street smart kid,” said Vredevelt, who was a criminal defense attorney for 25 years and now represents boxers. “ ... He’s had quite a crazy life and we kind of talk to him every day about doing the right thing and staying the course. I think I talk to Jerrico more often than I talk to my wife.”

Walton exacts revenge on his father’s alleged murderer

It’s been a more than crazy life. If it weren’t all documented by police records and news reports, it would be laughed off as a poor attempt at a rags-to-riches movie.

But Jerrico Walton’s life has been filled with murder, tragedy and extreme poverty, though you wouldn’t know it talking to him.

“When I think of my life, I never really had that male role model in my life I could look up to and I think a lot of what has happened to me has come as a result of me seeking that,” Walton said.

Holmes, his father, was rarely involved in his son’s life. For the longest time, Holmes denied paternity, and so his brother, Hakeem Holmes, took on that role for a while. His father denying paternity created a void in his life.

“He would say that I wasn’t his child and that’s why he wasn’t involved in my life,” Walton said. “But he knew I was his son. He just didn’t want to take on the responsibility. My Dad was selling drugs and he ran the streets. He was about that life and he was in and out of jail.”

As father and son were trying to mend their relationship not long after Katrina sent the family to Texas, another tragedy hit. On March 7, 2007, John Sebastian Holmes was positively identified by the coroner in Galveston County, Texas. His body, and that of 22-year-old Adrienne Nicole Lincoln, were discovered in the trunk of a car that had been reported missing on Dec. 26, 2007.

The bodies were discovered after a maintenance worker for an apartment complex smelled a foul odor coming from the car and called police.

“My Dad was finally starting to do some things as a father,” Walton said. “He was trying to handle his business and do the right things. He told me he was going to bring me a dirt bike for my [Dec. 4] birthday, but he never made it.”

Walton had never been a problem child despite the hardships he’d faced until his father’s body was discovered in the trunk of that car.

It threw his life into a downward spiral. He joined a gang and began running the streets. He didn’t care about school.

The word on the street was that a long-time associate of his father’s, a man named Brandon that everyone referred to as “B,” was responsible for the murder. Police, though, hadn’t made an arrest.

Walton encountered the man in Houston, and his life changed for the worse yet again.

“He was at this apartment and I happened to see him,” Walton said. “Everyone knew he was the one [who murdered] my Dad. When I seen him, I just ran up on him and started shooting.”

Jerrico Walton was still only 14. He tells the story dispassionately, like he’s telling details of a movie he’s seen.

“Honestly, like I did it but I didn’t even know I shot him,” Walton said in a statement that, on the surface, doesn’t make sense. “I just was hurt and I was crazy and I wanted revenge for my Dad. And I seen him and I shot him three times.”

Vredevelt, who said he’s got many 3 a.m. phone calls about issues that happened to his clients, said he thought he understood what Walton meant when he said he didn’t know he’d shot “B.”

“I think he’s repressed a lot of it to be able to kind of move on and live his life,” Vredevelt said.

A month after “B” was shot, Walton was arrested. He was tried as an adult and was facing 60 years, but when he was convicted, he was sentenced as a juvenile. He spent four years in the Al Price Juvenile Correctional Facility in Beaumont, Texas.

That stint would change his life yet again.

While serving his time, Walton turns to boxing

He turned to the Bible while he was in jail and said, “I prayed to God that He would still keep me and love me,” Walton said. “I got lucky. I got deeper into my faith. Jail can either make you or break you. It’s what you make of it, and it made me a better person. I learned to think before I react.”

He met a staff member he remembers as “Mr. Reggie.” Mr. Reggie encouraged him to learn how to box.

Boxing has been a way out of trouble for young people for years, because it creates discipline and often gives them meaning and focus in their lives.

Walton was an athlete of some note, but he didn’t take to boxing right away.

“I didn’t feel like I was good at it at all,” he said. “I’d never fought before, and it was weird. But I stuck with it and I eventually got good.”

He fought a couple of times in jail, and then had seven amateur fights. He didn’t have any prospects for a job or to make a living. As Vredevelt said, “I don’t think he’s ever had more than two tens to rub together his entire life.”

Needing the money, he turned pro. And for once in his short life, he got lucky. Washington and his wife attended a card in Houston in which Walton would be fighting. Walton scored a knockout and the two met in the locker room area.

Washington was a well-known strength and conditioning coach in Houston who worked with 75 or so athletes. Walton wanted to join them.

Washington’s first impression after putting him through a workout wasn’t exactly positive.

“It’s like 15 minutes into the first workout we’re doing and he runs out of the gym and throws up,” Washington said. “I kind of laughed and said, ‘Well, he won’t be coming back.’ But I was surprised the next day, there he was again. Once again, 15 minutes into the workout, he runs outside and throws up again. And I thought that for sure that was it after two days of the same thing.

“But he never stopped coming. I was impressed by the fact he wanted to do this. My fighters are like family to me and as we worked together more, we got closer and closer. Jerrico never had a situation like that. I took him in and he was the closest thing I had to a son. He started calling me Dad. For the last five years, that’s been it. We have had that father-son relationship.”

Washington became one of his three co-managers, along with Vredevelt and former NBA player Mike James, who was the first to see potential in Walton.

They helped him with his issues, set up businesses for him and pay him a salary so he doesn’t blow his money on the day he gets it.

By the time he was 12-0, he sought out Shields, hoping for more individualized attention. Shields was stunned at how much potential Walton had.

“This kid could fight and I never had heard of him in the amateurs,” Shields said.

That, of course, was because he barely had an amateur career to speak of, and Walton was learning on the job as a pro.

His life has turned around remarkably, though he’s had his ups and downs. He admits to an arrest on a drug charge, but Vredevelt said he had a joint in his career during a traffic stop. That case was dismissed.

He still has his moments that cause his managers and those close to him to worry. One night last October, he went with his best friend, Byron Williams, to a bar in Houston.

The two got separated, and Walton noticed Williams getting into a dispute with another man that he says he did not know. They went outside and Walton went out to see what was going on.

“I saw the guy shoot him and then he ran away,” Walton said. “I’m going crazy saying, ‘Oh my God, I can't be going through this again.’ I have had deaths all my life. Not only my father. Both my uncles, Daniel Walton and Steven Pearce, were murdered. Now here was my best friend.”

He kept encouraging Williams until an ambulance arrived. Williams died at 26 along with a woman, 31-year-old Brittany Magee. No arrest has been made.

Walton said he’s still grieving the loss of his friend. It was the one time he spoke in a monotone, with little life in his voice. Even when he spoke about his father’s death, it was different.

He learned his lesson from his father’s murder, though. He’s never so much as thought about avenging Williams’ death. He hopes to be able to use the tragedy he’s endured in his life to make a difference in the lives of others.

“I’ve been through so much that there is nothing anybody can be going through that I can relate to on a very personal level,” he said. “The thing is, someone needs to make a change and break this cycle of violence so it doesn’t tear up the next generation. I want the world to know my story and all of my trials and tribulations because I know I’m going to make it and I’ll be the guy who can be the example for others to point at.

“Parents talk to their kids and I guess that is good, but they can’t relate to their kids the way I can because I was one of them. I had nothing and everything was going wrong and I survived it and I’m doing good.”

He laughs at that last phrase, I’m doing good. He’s overcome an enormous amount of tragedy in his 29 short years and he’s on the verge of making it big.

“My story is going to be an inspiration to others and hopefully be the one that ends this cycle for the next generation,” he said. “That’s why I’m an open book. Kids who have a background like mine will be able to see me and can relate to me in a way they can’t relate to too many others. Helping them is my main motivation now.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

money

money