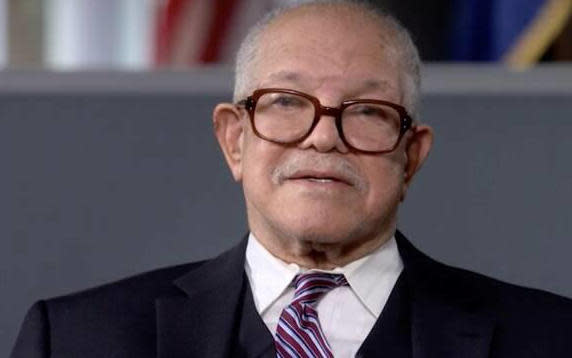

Black veteran's nearly 60-year wait for Medal of Honor may almost be over

Vietnam War veteran Col. Paris Davis (ret.) has been waiting for his Medal of Honor nomination to be approved for nearly 60 years, after the award packet of recommendations for him vanished at the height of the civil rights movement — twice.

But it has now finally reached Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin's office for approval, a military official tells CBS News. If Austin adds his name to the list of those who have recommended Davis be recognized with the nation's highest military combat award for his heroism in Vietnam, the packet would go to President Joe Biden's office for final approval, marking the end of Davis' decades-long wait for recognition.

Davis gave his first television interview to CBS News last year about the renewed Medal of Honor effort. One of the first Black officers to be part of the Army's Special Forces, Davis' courage and valor earned him the respect of his soldiers in Vietnam, and a nomination for the award.

In June 1965, Davis, then an Army captain, led a nearly 19-hour raid northeast of Saigon.

"We were stacking bodies the way you do canned goods in a grocery store," Davis recalled in an interview with CBS News senior investigative correspondent Catherine Herridge. Though he'd been hit by a grenade and gunfire, Davis would not leave behind Americans Billy Waugh and Robert Brown. Both were gravely injured — and Brown had been shot in the head, Davis said.

"I could actually see his brain pulsating. It was that big," Davis said. "He said, 'Am I gonna die?' And I said, 'Not before me.'"

Davis said he was twice ordered to leave, but according to an interview he gave in 1969 to then-local TV host Phil Donahue, he responded to his commanding officer, "Sir, I'm just not going to leave. I still have an American out there."

"He told me to move out. I just disobeyed the order," Davis told Donahue. By Davis' side during the 1969 TV interview was Ron Deis — now the team's youngest survivor.

Deis later recalled Davis' actions that day to CBS News and was visibly emotional.

"Captain Davis refused and said, 'No, I'm not leaving while I have men out on the field,'" he said.

In April 2021, in a rare interview, the sole surviving witness to Davis' actions, 91-year-old Billy Waugh, described to CBS News how he had been shot multiple times in the legs and was unable to walk.

"We ended up in an open area together," Waugh said. "He (Davis) grabbed me, and he drug me."

Waugh, who went on to have a storied career in both the Special Forces and the CIA, confirmed he was the sergeant identified in Davis' December 1965 interim Silver Star citation. That is typically awarded while a Medal of Honor packet is being processed. That document, which memorialized Davis' heroic actions, is the only surviving record from the original Medal of Honor packet.

At the 5th Special Forces Headquarters in Nha Trang Vietnam, Waugh, badly wounded and soon heading to Walter Reed for nine months of medical treatment and rehabilitation, said that he personally submitted Davis for the Medal of Honor.

"I just described the action and tried to describe it best I could," he said. "And I wrote what I had seen and what I participated in and made him look good, as he had done. I can't describe where he was part of the time, because I was not with him. We were split (by gunfire), then we came back together."

Waugh said he submitted the paperwork and heard that it was making its way through the system. Davis' commander, Billy Cole, also recommended Davis for the medal.

But Davis never received the award — his file vanished in Vietnam that same year, in 1965. A 1969 military review "did not reveal any file on Davis," according to the Defense Department.

In 1981, with no award for Davis, Waugh said he wrote a personal statement.

"I wanted to re-do it, to see why it hadn't gone," he said.

Neil Thorne, who volunteers his time to recover medals for overlooked veterans, compared the Medal of Honor nomination paperwork he recovered through the Freedom of Information Act to gold.

What makes Davis' case stand out, Thorne said, was that it was lost.

"Everybody I've talked to that served under him says that he's the best officer they've ever served under," he said.

Thorne said the loss or destruction of Medal of Honor paperwork is "very uncommon," adding that "there would've been multiple copies."

In 1969, after a military hearing into the status of the Davis Medal of Honor nomination, the Army was ordered to submit a new packet "ASAP" for Davis, but for a second time, there is no evidence that a Medal of Honor file was created.

Waugh, whom Davis carried to safety, wrote in a 1981 statement, "I only have to close my eyes to vividly recall the gallantry of this individual."

Over the years Davis' fellow soldiers also lobbied Congress. But each time, the process stalled.

"I know race was a factor," Davis said — a factor he says he experienced during his 23 years in the Army. Davis told Herridge he was one of the first Black officers in the Green Berets. He recalled telling troops, "you can call me Capt. Davis ... but you can't call me a n*****." But "it did happen," Davis said.

He recalled an encounter with another pilot he had rescued while on a different mission.

"I saw him at Fort Bragg with his wife and his kid, they saw me. He went on the other side of the street, so we wouldn't have to speak," Davis said. "If that had been a White guy, you know, he would've gone over, and hugged him. That's racism."

During the interview, Davis also said soldiers forget color when under attack. "When you're out there fighting, and things are going on like that, everybody's your friend, and you're everybody's friend...the bullets have no color, no names."

Asked if the battlefield was an equalizer, Davis said "Always."

Only 8% of Medal of Honor recipients for Vietnam are Black.

As for Davis, there is new momentum to recognize his case as the celebrated veteran approaches his 84th birthday.

"We're all trying to right a wrong," Ron Deis said.

Asked what it would mean to him to have his service honored, Davis replied, "It would mean all the things that I haven't been able to dream about."

An expedited review of Davis' nomination was due in 2021. The packet was previously signed by then Secretary of the Army Mark Esper, and more recently by the current Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth.

Asked if Davis still deserves the Medal of Honor, Waugh said, "Well, that's never going to… can't change. That cannot change, wouldn't change in my mind. My mind is fixed on it. I may have a simpleton mind, but it doesn't change too much, and when it comes to awards such as that, it's pretty well up front [in] my mind. Davis did a good job, and I am proud of him."

A spokesman for the Office of the Secretary of Defense told CBS News the department doesn't discuss the stages of progress of any award nomination because it would be "inappropriate and unfair" to the award review, deliberations and any potential award recipient.

Military.com first reported the new status of the Davis Medal of Honor packet.

Prince and Princess of Wales begin Boston visit as royal scandal erupts

Thousands of Minnesota nurses vote to authorize 2nd strike this year, up to 20 days

FDA considers change to blood donation policy for gay and bisexual men

money

money