'Back-alley butchers,' dead women, doctors arrested: What life was like before Roe and what could happen next

She climbed onto a table in a shabby Indianapolis workroom, nervous and frightened, and nudged her feet into the stirrups. The doctor gave her no anesthesia – just a piece of gauze to bite down on.

Stop crying, he said. Be quiet.

When it was over, he told her to go home and “buy some pads, because you’re going to bleed.”

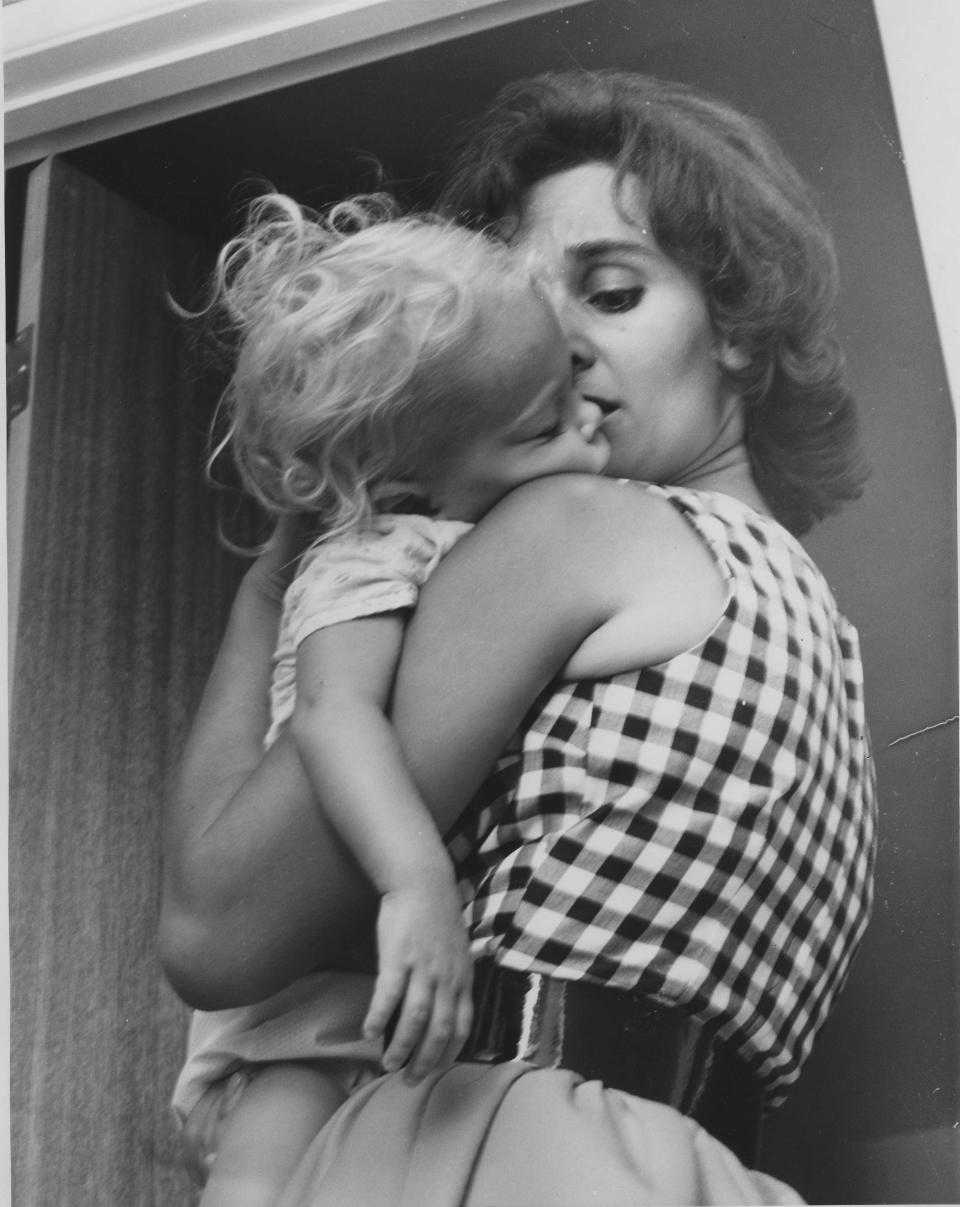

Sandy Lessig was a senior in high school with big dreams, and at 18, she couldn’t afford and didn’t want a child. But the birth control she and her boyfriend had used had failed, and now, just months from graduation, she was pregnant.

It was 1968. Abortions were largely illegal in Indiana, as they were throughout the country five years before Roe v. Wade established a national right to the procedure.

She’d pulled up to the building in tears, past broken streetlamps that at first obscured the address, alone and scared in a neighborhood she would rather not have been in at all. At cheerleading practice, at her after-school job at a shoe store, this appointment was all she could think about.

The doctor was performing abortions out of a nondescript building to make ends meet. She wondered if he'd lost his license. There was no receptionist. No waiting area. No emotional support. Just a room with a table.

“You opened the door and there it was,” Lessig recalled.

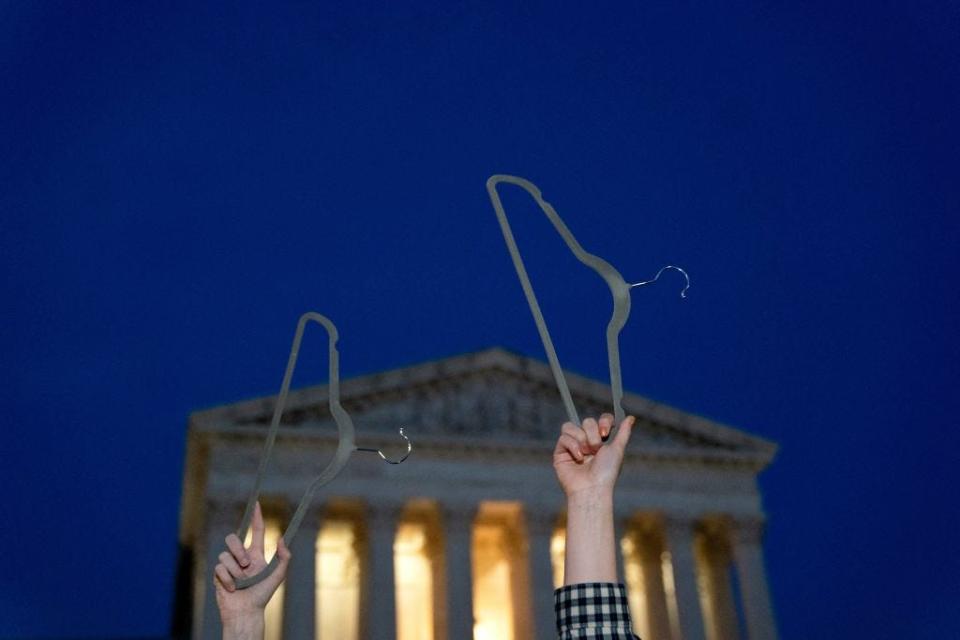

As the country readies for a possible undoing of Roe v. Wade, those who faced the issue head-on in the years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1973 nationwide legalization of abortion remember a time when information was scarce and doctors fielded desperate pleas for help, from women seeking to end their pregnancies or those whose illicit deals with “back-alley butchers” had gone horribly wrong.

They worry about the possibility of a post-Roe world that, while safer and teeming with more information and options, still poses the threat of shadowy transactions and unscrupulous operators capitalizing on despair as states clamp down on the procedure.

From a Kentucky obstetrician who witnessed the bloody aftermath of coat-hanger operations to a California congresswoman who sought her own abortion in the 1960s, they, like activists and historians who chronicled the era, fear that the disparities they saw play out in a pre-Roe society will rebound in a post-Roe one. The moneyed and well-connected will have more and safer access to abortions or abortion medications in states that outlaw the procedure, while low-income people of color will likely suffer most.

According to the Institute for Women's Policy Research, access to legal abortion reduced teen fertility, increased high school and college graduation rates and increased women's workforce participation, with the benefits especially pronounced among Black women, who typically had lower access to contraception.

“We’re talking about a racial justice issue,” said Christian Nunes, president of the National Organization for Women (NOW). “We’re talking about economic justice issues.”

The women least likely to access abortion and quality reproductive care, Nunes said, are historically Black and brown, poor or from marginalized communities. Without Roe, “they’re going to be driven to areas of desperation, of trying to find ways to resolve it themselves.”

While advances in medicine and technology have made abortion safer and produced effective abortion pills, the emergence of a thriving anti-abortion movement has reordered the landscape.

“There will be much more legal surveillance,” predicted Carole Joffe, a professor at the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health at the University of California-San Francisco. "Black and brown women are going to be the major people who get arrested or who get injured, or even die.”

Despite her experience, Lessig, now 72, considers herself fortunate. She recalls reading obituaries of women who'd bled to death or developed sepsis after illegal abortions. "It was all very hush-hush," she said.

And while her hapless doctor’s work hadn’t been precise, requiring follow-up procedures and antibiotics, the abortion was performed by a practiced provider rather than a fly-by-night amateur. Lessig went on to college, enjoyed a rewarding career, got married and had two children.

Today, as a volunteer at Houston’s Planned Parenthood clinic, where she holds the hands of those facing the same decisions she did as a teen, she fears a post-Roe future.

“It’s going to be disastrous,” she said. “We’re going back to making this go underground.”

Finding providers 'was really a crapshoot'

In the years before Roe, those seeking abortions and who had the financial means traveled to Mexico or Puerto Rico; others flew to Europe or Japan.

“If you could afford to get someplace else, you had a good chance of getting a safe abortion,” Joffe said.

State laws at the time generally prohibited abortion except for those authorized by physicians – typically when the mother’s life was in danger, or in cases of rape, incest or severe fetal deformities – but criteria could be wildly subjective, and it helped to have connections.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Others in need of an abortion relied on word of mouth or nose-to-the-wind instincts, whether college dorm chatter or underground newspapers. They consulted doctors and nurses, hoping for referrals.

“It was really a crapshoot who you ended up with,” Joffe said.

A sympathetic physician might induce a miscarriage, then send the patient to a hospital – but that risked subjecting them to questions from authorities about the circumstances that had gotten them there.

“They would be questioned by hospital staff,” said Leslie Reagan, a history professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and author of “When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine and Law in the United States, 1867-1973.” “Like, ‘Who did this? Where did it happen? Who’s the father?’ Or they would call in the police. There were a lot of women who came in miscarrying who were treated like criminal suspects. I expect we will see that again.”

In some places, Reagan said, authorities conducted raids, hoping to catch practitioners in the act. Women weren’t prosecuted but were threatened if they didn’t testify.

“They were told, ‘Your name will be in the paper’ or that they would be held as a hostile witness,” she said.

Estimates of illegal abortions in the 1950s and 1960s ranged from 200,000 to more than 1 million annually, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research group supporting abortion rights.

By 1967, the situation had prompted a group of rabbis and ministers led by New York Rev. Howard Moody to found Clergy Consultation Service, a network linking people with abortion information and reliable providers. The national network ultimately grew to include 3,000 clergy in 38 states.

Before the 1973 Supreme Court decision, 17 states had legalized abortion to varying degrees beyond those necessary to save a woman’s life, providing growing options for those in states where the procedure was still illegal – provided you had the wherewithal.

But for the financially strapped, choices remained few.

'We're going into an unknown'

From 1964 to 1966, Ronald Levine started each shift at the University of Louisville General Hospital in Kentucky by thinking to himself: What would today bring?

In an emergency room tending to the uninsured, the young medical resident had witnessed before the horrors of botched back-alley abortions or dicey attempts by women and teens to self-induce, relying on the minimal knowledge available in 1960s America.

Infections provoked by coat hangers blindly probing for the uterus. A girl who had repeatedly douched herself with lye, “so literally her whole vagina was closed,” remembered Levine, now 93.

“Girls didn’t know what to do," he said. "They just did whatever they heard. Not a week went by where we didn’t have somebody on death’s door.”

The experience had hit Levine like an Arctic airburst after his stint as a ringside physician where, fresh from the University of Louisville Medical School, he’d treated an 18-year-old Cassius Clay before the budding champion headed to Olympic glory in Rome.

Now he was comforting panicked girls and women, many in septic shock or close to it. They hadn’t known any better. The boys or men in their lives understood even less. Abortion wasn’t discussed until desperation slammed it onto the table.

A young department head had responded by authorizing huge blasts of penicillin, and somehow, in Levine’s three years of residency, not a single patient died.

“We saved a lot of people’s lives by doing that,” he said. “They did terrible things to themselves, or they had terrible things done to them by abortionists who didn’t know much more than they did. It was a bad time. I hope to God we don’t get back there again.”

Ultimately, Levine would become chief of gynecology surgery at the University of Louisville. But as a family physician, he recalled office visits by teens seeking to end their pregnancies, some he knew to be the daughters of fellow physicians. Another crept in with her mother, “a sweet Catholic woman” he recognized as a sometime patient; the 14-year-old had been impregnated by a next-door neighbor’s 15-year-old son. As with the others, Levine directed them to a safe provider.

“These are the people I’m afraid for, the teenagers,” he said of the possibility of a post-Roe society.

The world is different, Levine knows. Teens are savvier and can access much more information than their pre-internet counterparts.

“It’s going to be better, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be good,” he said. “We’re going into an unknown. There will be ways to find pills that weren’t available 50 or 60 years ago, but there will also be people out there wanting to make a dollar who are going to do bad things, and you just hope that it doesn’t happen to your daughter or your sister or anyone you know.”

A series of events sway public opinion

Several events in the 1960s helped shape public attitudes about abortion.

In 1962, a doctor authorized an abortion for Phoenix children’s television host Sherri Chessen after discovering that the sedatives she’d been taking – bought by her husband while in Europe – contained thalidomide, which made her fetus subject to deformities.

Hoping to prevent other couples from facing the same situation, she granted an anonymous interview to the Arizona Republic, which nonetheless identified her. The publicity prompted the hospital to cancel the procedure, fearing prosecution despite the doctor’s recommendation.

While Chessen was harassed and received threats, many more supporters mobilized behind her. She eventually got an abortion in Sweden, where the obstetrician told her that the fetus, with no limbs save an arm, would have been born dead. Chessen's story was made into a 1992 TV movie starring Sissy Spacek.

“That really shifted public opinion in a positive way,” Joffe said.

Two years later, an incident involving a Connecticut woman helped fuel the abortion-rights movement. Gerri Santoro, 28, had left her abusive husband in California and returned home with the couple’s daughters. She began a new relationship with co-worker Clyde Dixon and became pregnant, and when her estranged husband called to say he was coming to visit the children, she feared for her safety.

She and Dixon checked into a motel in June 1964, where Dixon, using surgical instruments, fumbled a textbook-guided abortion. When Santoro began to bleed to death, Dixon fled; after Santoro's naked, kneeling body was found the next morning by a maid, a police photograph of the scene leaked and became a symbol of the abortion-rights movement.

“When I was in college, I would go to abortion marches and see people carrying pickets with that picture on it,” Joffe said. “Stories were starting to get out about people who died.”

Then, in 1966, California’s Board of Medical Examiners prosecuted nine physicians affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco who had done abortions for women exposed to rubella after studies showed the risk of fetal deformities.

“It showed the gray area in which doctors were operating,” Joffe said.

The effort, however, backfired, as doctors and medical school deans nationwide defended the physicians' decision. More significantly, Joffe said, it swayed the American Medical Association to push for liberalized abortion laws. The charges were ultimately dropped.

'I was getting a second chance'

In 1966, Renee Chelian was a 15-year-old in Detroit when she found she was pregnant. She hadn’t even heard of abortion, so her plan was to marry her 16-year-old boyfriend.

“I was packing my suitcase and my parents came in to talk to me,” said Chelian, now 71. “When they brought up abortion, “I was like, ‘What is that?’ They explained I wouldn’t be pregnant anymore. I literally felt like God reached out and gave me a hand. I would not have to get married. I would not have to quit school. My life would be the same. I was getting a second chance.”

Shame and secrecy enveloped the planning. Unlike fathers-to-be, she said, pregnant girls were tossed from school. Chelian recalled her parents speaking in coded words over a telephone party line as they arranged the clandestine service. Her boyfriend’s father would pick up the hefty $3,000 bill.

She and her dad drove to a prearranged location. When they got there, they were fitted with blindfolds and hustled into a car.

When the blindfolds finally came off, Chelian thought: This is definitely not a medical facility.

They were sitting in a warehouse with a few dozen folding chairs, many occupied by others who, just like her, had come to get abortions.

She stared at the oil-stained cement floors, afraid to look up. “Mostly what I remember is seeing a lot of feet,” she remembered.

When it was her turn, she was given a sedative. They told her after that her pregnancy was further along than expected, and that she would pass the fetus at home in a day or two.

That didn’t happen. Their family doctor connected them with an obstetrician-gynecologist who surmised that her uterus had been packed with gauze to create irritation and stimulate contractions. He ordered antibiotics to help prevent infection.

Eventually, Chelian did pass the fetus. The people who performed the abortion picked it up for a $200 fee. Chelian’s father had been protective and supportive throughout the process, but when it was over, he said he never wanted to speak of it again.

Chelian went on to study nursing, and based on what she would learn, she estimated she was 14 to 16 weeks pregnant at the time of her procedure. She now operates three Northland Family Planning Centers in the Detroit area, working to ensure that women seeking abortions experience the antithesis of a grease-stained warehouse.

The prospect of Roe being overturned and a patchwork nation where abortion is either permitted or forbidden reminds Chelian of her work in pre-Roe Buffalo, New York, where she traveled on weekends to work with a doctor performing abortions in one of a handful of states that had legalized the procedure.

Women would arrive from multiple states, and Chelian recalled making the four-hour drive through snowstorms, inching around tractor-trailers toppled by the wind. But no matter how bad the weather, by the time she got to the Buffalo clinic, “there were always patients there.”

Bans won’t stop people from seeking abortions, she said.

Fears of heightened surveillance, criminalization

At a Congressional hearing last fall, in the wake of Texas' decision to ban abortions after six weeks, U.S. Rep. Barbara Lee, D-California, shared her own 1960s abortion experience as part of a plea to preserve and expand abortion access.

“I’m compelled to speak out because of the real risks of the clock being turned back to those days,” she said in her testimony.

At the time, she told her fellow lawmakers, she was an accomplished student and pianist and her California high school’s first Black cheerleader. After learning she was pregnant, she worried that if anyone found out, "my life would be destroyed," she said.

A family friend arranged for her to have the procedure in Mexico, and the experience would ultimately inspire her to fight for abortion rights as a legislator.

“A lot of girls and women in my generation didn't make it,” she said at the hearing. "In the 1960s, unsafe, septic abortions were the primary killer of African American women. My personal experience shaped my beliefs to fight for people's reproductive freedom.”

Should Roe fall, 22 states have laws or constitutional amendments poised to activate immediately or soon thereafter to ban abortion, while four others have signaled intent to follow suit. Of states not instituting bans, most in the Northeast or along the West Coast, 16 of them protect the right to abortion at least through viability, as does Washington, D.C.

Lawmakers in some states, emboldened by a recently leaked Supreme Court opinion pointing toward a redo, are already looking to ban or severely limit abortion or to criminalize use of medication abortion. More than a dozen states, including Texas, Oklahoma and Alabama, have passed or are considering laws that could imprison individuals who perform abortions. In Louisiana, proposed legislation would enable prosecutors to charge those who get or provide abortions with homicide.

Reagan, of the University of Illinois, fears law enforcement may employ pre-Roe tactics, noting last month’s arrest of a 26-year-old woman in far south Texas on a murder charge for “the death of an individual by self-induced abortion.” While the charge was ultimately dropped, the chill it produced in the community has lingered.

“When the anti-abortion movement claims that women won’t be punished – well, they will be,” she said. “You don’t need this to happen to many people to really frighten others that this could happen to them.”

60% of people seeking abortions are already mothers and 75% are living below the poverty line (per Guttmacher Institute).

We need to reframe "pro-life" as being pro paid leave, pro affordable child care, pro affordable housing, pro health care #facts #abortionrights— Women's March Foundation (@wmnsmarchla) May 5, 2022

When women are forced to carry pregnancies they don’t want, Reagan said, “that can have serious effects on people’s lives. We don’t have available childcare for everybody. Some will drop out of school or delay returning to the labor force. Having to carry a pregnancy also keeps people in relationships they may not want to be in because they need the financial support.”

According to the Guttmacher Institute, 60% of women seeking abortions are already mothers, while half live below the poverty line.

Curtis Boyd, a semi-retired physician in Santa Fe, said women will struggle to find their way to places where abortion is legal, “but getting to that other state is difficult – you have to get off work, maybe arrange for childcare and then pay for the abortion, and many women are going to find it impossible.”

In the mid-1960s, Boyd, an ordained minister, was among those who joined the growing Clergy Consultation Services network. He performed discounted $100 abortions in a small clinic in Athens, a small city 80 miles southeast of Dallas.

“I could never see all the patients that wanted to come, even though I was working six days a week, 10 to 12 hours a day,” said Boyd, now 85. “The need was tremendous.”

He’d been moved by the women’s perspectives he’d heard while involved in social justice efforts, convinced of the need for abortion rights.

“They said, ‘We cannot have equality and equal opportunity if we cannot control our reproduction. We have to be able to plan when to have a child,’” he said. “Abortion is the capstone that holds up that arch of women’s rights.”

One day in 1969, a tiny woman from San Antonio appeared in sandaled feet and ragged clothes, hoisting a sack of personal belongings. Boyd remembers tortillas among the items peeking from within. In her 20s and speaking little English, she told Boyd she was pregnant but had several children already and didn’t want another one. She handed him a crumpled five-dollar bill.

Boyd learned that she had come in by bus the night before and walked to the community hospital, a place she considered safe. She’d hid in a bathroom stall and slept there overnight, then awoke and washed up before walking to his clinic the next morning.

She was among hundreds who showed up annually begging to be seen, who’d pack his waiting room for hours, from college students to low-income moms referred by local ministers. They’d hitchhiked, taken buses or packed into Volkswagen vans, “any way they could manage to get to East Texas and show up at my door,” he said. He said it was the most compelling and valuable work he’d ever done.

But the number of women and vehicles with out-of-state plates showing up at Boyd’s office had started to raise eyebrows among authorities.

“I think they thought I was dealing drugs,” he said.

Now, with this weary woman before him, Boyd had a decision to make.

He handed back the $5.

The abortion would be a gift for the courage she had shown, he told her.

The woman smiled. Gracias, she said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Illegal abortions: Before Roe, women risked death, danger, deception

money

money