How an Arizona tribe and wildlife biologists rescued the Apache trout from near extinction

WHITERIVER — High in the White Mountains, Renaldo Dazen pulls his yellow Ram pickup truck, affectionally named “Bumblebee,” through the ponderosa pine-lined roads that follow the natural curves of the White River.

Dazen, a councilman for District 2 of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, was born and raised here. He points out rock cliffs in the shape of a woman, the high school he attended, the hospital where his daughters were born, and he has a story for just about every dirt road and swimming hole on the reservation.

The White Mountain Apache reservation stretches across about 1.24 million acres in eastern Arizona, rising at its highest point to 11,000 feet above sea level. It is the only place in the world where the state fish of Arizona lives in its natural habitat .

The Apache trout is deeply woven into the fabric of this part of the state and locals speak of the fish as if it is a legend. The barista at a coffee shop in nearby Pinetop banters with a regular about catching and cooking trout (her favorite way is smoking it) as he was heading out for a trip. The coffee-drinking angler across the counter admits he has never caught an Apache trout.

And that’s not surprising. The Apache Trout has been a threatened species for nearly as long as it has been properly recognized. Formerly known as ‘yellowbellies” (because of their distinct golden belly) the Apache Trout got its new name in 1972. A year later it was among one of the first species to be recognized as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, a measure the U.S Supreme Court at the time called, “the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species enacted by any nation.”

One year after that, the fish was downlisted to threatened to allow for recreational fishing, with restrictions.

Now, almost 50 years later, the days of the Apache trout as a ghost story for locals may be nearing an end as its population numbers continue to recover.

In August, U.S Fish and Wildlife Service announced the completion of a five-year status review, which recommends delisting the species from the Endangered Species Act.

The Service will next publish a proposed rule in the Federal Register to delist the Apache trout, with a 60-day public comment period seeking input from government agencies, the scientific community or any other parties concerning the proposed delisting.

How stocking killed the Apache Trout

In the late 1800’s the Apache trout could be found in 680 miles of streams in the White Mountains. Recent counts estimate they currently occupy 30 percent of those original 680 miles.

The Apache trout faced a series of hurdles that led to a decline in its numbers. Overfishing, crossbreeding with non-native trout, habitat loss caused by wildfires, human destruction of riparian vegetation, livestock overgrazing, and water diversion and channelization of streams all contributed to the losses.

In the early 20th century fishermen and locals noticed a decline in their main food source in the spring and summer months, mostly attributed to overfishing and the effects from cattle grazing.

“As settlement came up there into the White Mountains, there were a couple of things that contributed to the demise of the of the fish,” says Alan Davis, chair of the Arizona Council of Trout Unlimited. “Overfishing was one of them, but that was just one part of it.”

That’s when state and federal agencies first stepped in. Their plan to slow the shrinking numbers of Apache trout was simple: introduce new species of trout into the streams of the White Mountains to replenish the declining food sources for the growing number of settlers.

Brook and brown trout were introduced first. But once these non-native fish entered the water, they began feeding on the younger native fish who had lived there all along.

Rainbow and cutthroat were later added to the streams. Those fish began to cross-breed with the Apache Trout, slicing through purebred populations. It would be the main driver in what led to the major decline in numbers of the fish.

Aware of these threats, in 1955 the White Mountain Apache Tribe took the first steps to conserve the species by closing fishing on tribal lands where pure trout population remained. In essence, the tribe declared the fish endangered 18 years before the Endangered Species Act was enacted.

After the ESA, aggressive action was taken to grow and protect Apache trout populations. USFWS joined forces with the White Mountain Apache Tribe Game and Fish, as well as the U.S. Forest Service and Arizona Game and Fish Department.

Zachary Jackson is the project coordinator for the USFWS Arizona Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office in Whiteriver. He says the collaboration between agencies has allowed for increased and shared funding.

Once the tribe’s game and fish department closed Apache trout habitat to fishing where pure populations remained, the state wildlife agency stepped in and implemented various fishing restrictions, including bag limits on all species of trout.

Watershed management plans were developed, and conservation efforts shifted toward segregating non-native trout and Apache trout.

The effort to restore the population included a halt to stocking of non-native species in and near Apache trout habitats, construction of barriers to keep non-native trout out, and removal of those that were already there.

Endangered species: Wildlife managers say fish are recovering but may always need human help

And how stocking helped save the Apache trout

The Beatles heartfelt “Let it Be” plays over the radio as Bumblebee — with Dazen — travels downhill and into Williams Creek National Fish Hatchery near the appropriately named Trout Creek on the northern edge of the reservation.

Williams Creek is one of two fish hatcheries operated by USFWS on the reservation. The other is Alchesay National Fish Hatchery, named after the former White Mountain Apache Chief William Alchesay.

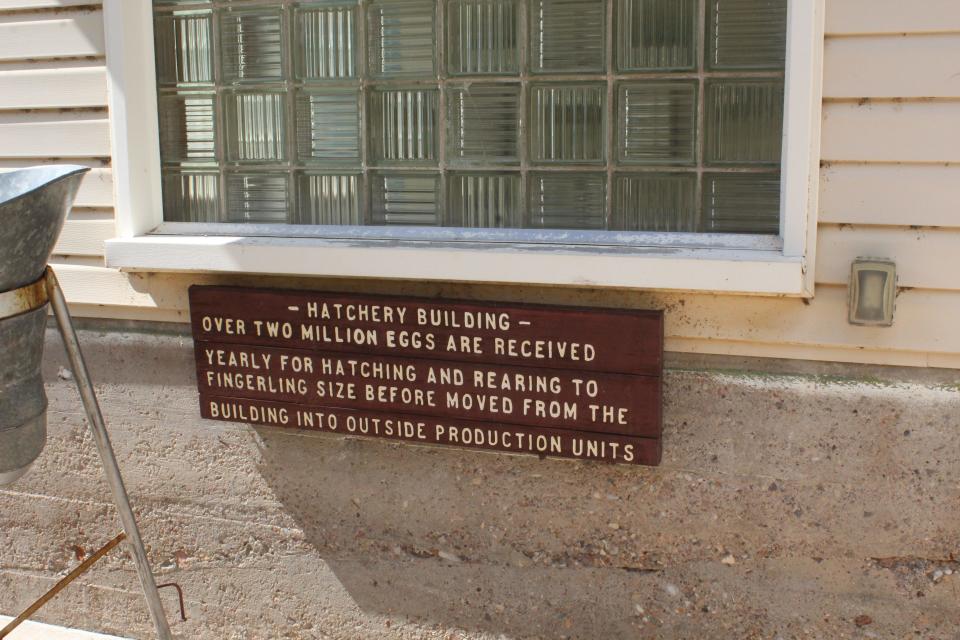

These fish hatcheries are responsible for spawning and stocking trout in local waterways. Apache Trout are spawned and hatched in Williams Creek.

USFWS uses a method of electrofishing, which shocks fish without killing them, to collect milt (reproductive fluid for fish) for hatching at the facility.

Bradley Clarkson is an Apache trout biologist at Williams Creek. “We get in the water and check to see if they have milt,” he says. “If they do, we preserve it and send it out to Atlanta, Georgia, where they have the facility that stores the milt.”

When April hits and spawning season begins the milt is shipped back here to begin the fertilization process.

Over two million eggs are stored inside the hatchery building annually. After hatching, the fish are kept in tanks inside until they reach 2-3 inches (about the size of a fingertip). The fish are then moved to outdoor “raceways.”

Raceways are artificial channels where thousands of fish will live before they are released into the wild once they reach about nine inches long.

“Some are 12-14 (inches) because we have to keep brood stock for two years,” Clarkson says of the larger fish on the property. “So, we keep those around a little bit longer.”

Each year the state receives 210,000 eggs from here to stock waterways on state lands. The tribe gets roughly 350,000 eggs for its land.

Clarkson has worked at the facility for 27 years and says the work done has been fundamental in restoring Apache trout populations to healthier levels.

Recovering species: Grand Canyon's humpback chub downlisted from endangered to threatened

Disease and climate change threaten conservation

Despite the success of management efforts, not all fish that come through the hatcheries can be released into the wild.

In 2018, in a massive blow to recovery efforts, federal hatcheries tested positive for a bacterial kidney infection, a disease so difficult to manage that all the fish that tested positive had to be killed.

Test are conducted by the hatcheries as well as at the state level.

Williams Creek collects variant samples from every female that is spawned at the facility and sends the samples to Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources Recovery Center in New Mexico to test for disease.

Clarkson says they are a disease-free hatchery.

But this past year the state rejected 20,000 fish that it believes were carrying disease that came from Williams Creek.

Climate change is also intensifying the complexity of management and conservation efforts post-delisting.

“It’s been difficult lately because weather changes,” admits the veteran biologist. “We don’t have enough water.”

On average, 1,500 gallons of water per minute are meant to move through the raceways at Williams Creek to maintain healthy water quality standards. On Sept. 15, 2022, that number was 1,270 gallons per minute. While this number sits below the average, both Dazen and Clarkson say that it is usually even lower, but an active monsoon season has helped.

“It’s been going down the last few years,” Clarkson looks over a covered raceway housing Apache trout and shakes his head. “The drought.”

The ongoing drought has dried out forests across the state and increased the chance for wildfires. These fires can undo years of progress and wipe out entire populations of fish.

In 2011, the Wallow Fire swallowed more than half a million acres of forest in the White Mountains.

It caused significant damage to the Fish Creek watershed, an area that, before the fire, had an adult population of over 1,000 trout, which is significant for a creek of its size. And a monsoon storm following the fire completely wiped out the creek.

Apache trout are a cold water trout and thrive in waters with temperatures in the upper 40-degree range. That’s why the White Mountains are a perfect home for them. Deep cool pools and ample cover from ponderosa pine trees serve as protection for the fish and are vital for their health and reproduction.

Wildfires cause sediment runoff that can not only sicken fish, but also cause pools to fill in, pushing fish closer to the surface where water is warmer. This also contributes to a loss of riparian habitat, leading to a poor rate of regeneration of instream cover.

Pine trees and vegetation killed by wildfire will also reduce the amount of shade rivers and streams receive.

Less tree cover results in more direct sunlight, warming streams. If the water reaches a median temperature of 66 degrees Fahrenheit, the Apache trout can experience reduced growth and their chance for survival drops significantly.

After the Wallow Fire, experts believed the best way to reach long term recovery goals was to focus on larger streams. Larger populations and larger streams are more resilient to long term droughts and fires.

Apache trout: Recovery begins at a Payson fish hatchery where a threatened species could thrive

Flowing forward, still plans to monitor

If delisted, Apache Trout will be monitored according to a post-delisting monitoring plan.

However, the Apache trout cooperative management plan (signed by all parties involved in conservation in December 2021) also includes commitments to monitor and manage Apache trout populations in perpetuity.

A main goal of the Apache recovery plan is to reach 30 genetically pure populations of Apache trout.

Today, 26 pure populations of Apache trout are currently protected by natural or artificial barriers developed through conservation efforts. Of those, 18 are free of non-native trout.

More than $2 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law’s National Fish Passage Program, will go toward removing certain barriers that are no longer needed thanks to successful non-native trout removal.

USFWS believes the fish are on the path to a brighter and more sustainable future and if delisted it would be thanks to more than half a century worth of collaborative work from fish experts, tribal leaders and volunteers with a passion for conservation.

Dazen calls the land and the wildlife who roam here “a gift.” The Apache trout is one of those gifts, swimming upstream here at their healthiest levels since before conservation efforts began.

There is a saying that the past is present on the White Mountain Apache Tribe, and today this iconic fish with a prominent past is a testament to that.

Jake Frederico covers environment issues for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send tips or questions to jake.frederico@arizonarepublic.com.

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Arizona tribe helps bring Apache trout back from near extinction

money

money