From Oklahoma City to Jan. 6: How the US government failed to stop the rise of domestic extremism

When FBI Special Agent Brian Murphy returned from an overseas posting in 2011, he expected his desk job in Pittsburgh to be far from the front lines of the U.S. war on terrorism.

Instead, he found that western Pennsylvania was a hot spot of another terror war of sorts, one involving formidable homegrown foes: white supremacists, anti-government militias and right-wing extremists.

That year, a young neo-Nazi was convicted of ambushing police in the working-class neighborhood of Stanton Heights, killing three officers and wounding another in a four-hour firefight.

Authorities also were investigating various militias and survivalist groups, including in rural areas northwest of Pittsburgh where six people were arrested three years earlier for allegedly stockpiling assault rifles, homemade bombs and a flamethrower to incite a race war.

Murphy, a newly minted counterterrorism supervisor, soon realized that there were many others like them, all heavily armed and seemingly ready to explode.

But when he tried to redirect resources from his international terrorism squad to a much smaller one focused on domestic extremism, Murphy ran headlong into a U.S. counterterrorism bureaucracy that he said appeared resistant, if not impervious, to change – a frustrating constant that would shadow his 23-year career.

He was far from alone.

For more than two decades, some federal law enforcement agents, like Murphy, have sounded alarms about the evolving threat posed by right-wing extremists in America. The FBI, the lead agency on domestic terrorism, has issued a steady stream of confidential warnings to state and local law enforcement. Private sector hate-watch analysts have called for reinforcements dozens of times.

Yet the U.S. government, under Democratic and Republican administrations, has repeatedly underestimated or failed to recognize the growing danger.

Under Donald Trump, the menace was inflamed by a president who aligned himself with far-right figures and conspiracy theorists and actively courted their support.

Federal authorities, meanwhile, prioritized international terrorism, particularly Islamic militants, even as deaths linked to domestic terrorism mounted while threats from abroad receded.

Washington failed to create a national strategy to counter right-wing extremism until the deadly siege of the U.S. Capitol last January triggered an urgent reassessment of the threat, according to USA TODAY interviews with dozens of current and former government officials and a review of government documents.

Federal agencies were slow to recognize the threat rising from the homeland and work together to counter it. Resources were poured into international terrorism while domestic extremist groups grew and operated in the open. Some key programs at the Justice Department and elsewhere were launched, stopped and then restarted. Investigators frequently lacked key sources to help them infiltrate movements and thwart attacks.

Overlaying all of that, current and former officials say, was the fact that the U.S. government lacked a coordinated and sustained strategy to combat right-wing extremism.

Now, one year after the assault on the Capitol, many of those officials question whether Washington is up to the task of containing a problem that has embedded itself deeply into the fabric of America.

“I am more concerned about the future of democracy than I am about any external threat to this country other than climate change," said Russ Travers, former acting head of the National Counterterrorism Center and, until October, deputy White House homeland security adviser. He blames extreme rhetoric in particular for politically motivated violence and domestic terrorism.

"Unfortunately," he said, "our approach to domestic terrorism focuses far more on symptoms than causes, and I don't believe the counterterrorism community – or the rest of the U.S. government – is adequately postured to address this threat.”

The Justice Department and FBI, responding to questions from USA TODAY, maintained that a cadre of prosecutors and agents have been working throughout the country's 94 federal districts and within about 200 Joint Terrorism Task Forces for years to combat the rising extremist threat to racial minorities, law enforcement, government targets and others.

Officials have credited that effort with helping to thwart a series of plots, from a 2016 plan to bomb a Kansas apartment complex housing Muslim immigrants to the 2020 breakup of an alleged kidnapping scheme targeting Michigan Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer led by anti-government extremists.

A Justice Department spokesperson described its network of U.S. attorneys as central to the "front lines" of the anti-terror effort that also includes far-flung partnerships with state and local authorities.

"Beginning as early as 2017, the Bureau surged resources to counter the threat posed by domestic terrorism, directing all 56 FBI Field Offices to prioritize and gather intelligence on the threat of domestic violent extremism," the FBI said in a statement.

Two years ago, the FBI said, it elevated the domestic threat to the same level of concern as the Islamic State international terrorist group.

But critics, including some lawmakers and current and former U.S. counter-terrorism officials, say Washington should have done much more, and much sooner.

The Biden administration has vowed a vigorous assault on all forms of domestic terrorism, especially right-wing extremism, which the government now casts as the most lethal threat facing the country. It includes thousands of Americans polarized to the precipice of violence by heated political rhetoric, propaganda, disinformation and other societal tensions.

The political conflagration that led to the Jan. 6 insurrection, the alleged Michigan governor conspiracy and other plots and attacks may have diminished to a flicker at times. But it has been burning, often unchecked, since long before the assault on the seat of American democracy.

“Racist mob violence and terror have been with us from the beginning of the Republic," said Rep. Jamie Raskin, the Maryland Democrat leading a House investigation into domestic extremism. "And there has been this fundamental ambivalence about whether the government is in some kind of silent complicity with racist violence or is actually going to confront and oppose it."

Echoes of Oklahoma City bombing era

When President Joe Biden vowed a new urgency to confront domestic terrorism, there were few equals to Merrick Garland in leading the strategy.

The former federal judge, a top Justice Department official in the Clinton administration, represented a direct link to the response to the nation’s deadliest domestic terror attack. On April 19, 1995, a truck bomb ripped the face from a federal office building in downtown Oklahoma City, killing 168 people, including 19 children.

The initial focus of suspicion was familiar: terrorists from the Middle East. Just two years before, al-Qaida-linked operatives had carried out the first bombing of the World Trade Center.

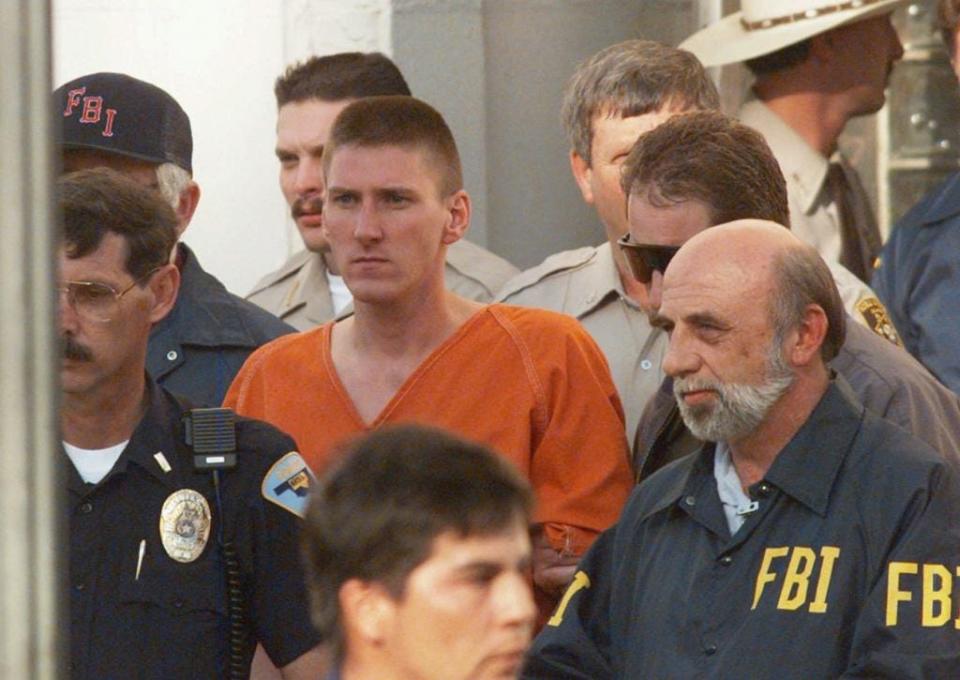

It wasn’t until two days later, when a young Army veteran from upstate New York was led out of an Oklahoma courthouse in shackles and an orange jumpsuit, that the nation awakened to a new breed of terrorism.

Garland’s oversight of the trials of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and accomplice Terry Nichols proved a masterclass in investigative and prosecutorial efficiency, quickly sending McVeigh to his execution and Nichols to life in prison.

Yet the success of the investigation and prosecution obscured the failures that preceded the attack.

Oklahoma City, current and former federal officials say, was the manifestation of an extremist movement with striking parallels to the forces that drove the deadly Capitol assault on Jan. 6, 2021. “The tone of the time was very similar,” said Dale Watson, a former FBI counterterrorism chief, recalling the wild churning of anti-government sentiment and conspiracy theories. At the same time, he said, even the most rigorous anti-terrorism program might not have uncovered the closely guarded plot among a handful of men.

But much like today, the system was blinking red for years in advance of it – and authorities either missed or ignored it.

The same forces were on display following the 2020 election. Militias, conspiracy theorists, and violent anti-government groups engaged in more than 100 armed protests at statehouses in the run-up to Biden's inauguration. Yet officials seemed blindsided by the Capitol assault.

Garland has said the investigation into the insurrection is the department’s top priority, telling a Senate committee at his confirmation this year that the country faces a “more dangerous period” than the powder keg of domestic tensions that preceded the Oklahoma City bombing.

More: 'Terror is still with us': Attorney General Garland returns for Oklahoma City bombing anniversary

But Garland and the rest of Washington have a lot of catching up to do.

Disappearing Domestic Terrorism Committee

Perhaps the most telling example of the federal government's episodic response is the Justice Department’s Domestic Terrorism Executive Committee, created more than 25 years ago in response to Oklahoma City. Its meeting scheduled for the morning of Sept. 11, 2001 was cancelled.

The committee, designed to establish a coordinated national strategy, didn't meet again for 13 years, according to current and former Justice Department officials familiar with it.

Joyce White Vance of Alabama was one of several veteran prosecutors who pushed to revive the task force as part of a more aggressive response to the rising right-wing threat after the election of President Barack Obama, the nation's first Black president.

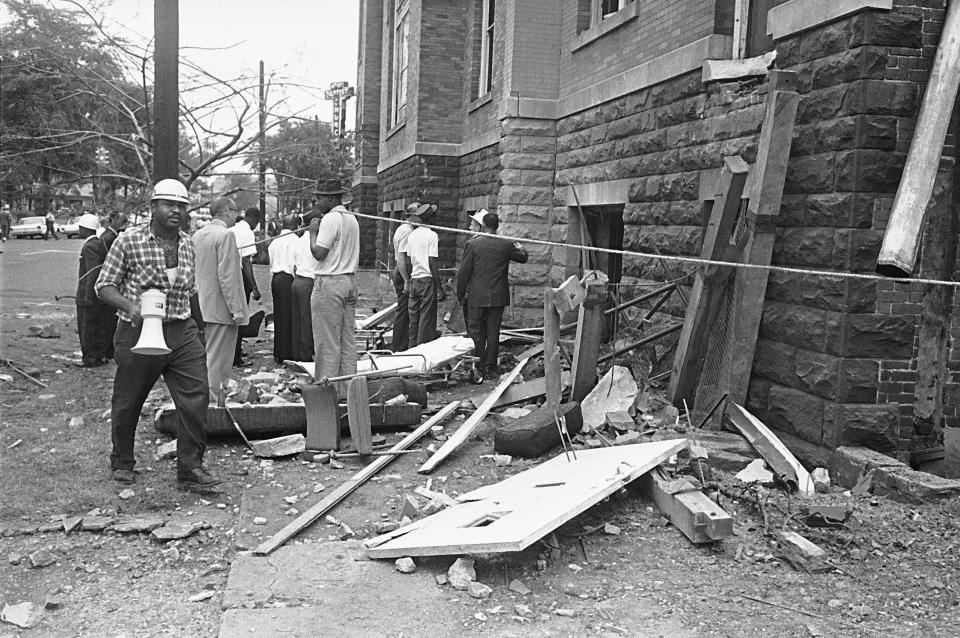

As U.S. attorney for Northern District of Alabama during the Obama administration, Vance battled an array of religious, political and anti-government extremists. Birmingham, her base, was the site of the 1963 Ku Klux Klan bombing that killed four young Black girls and partially blinded another.

“The issue that I wanted folks to appreciate was that whatever piece they were seeing in their district was part of a larger national issue,” Vance said. “And that was something that we knew because our experience in Birmingham was the terror that goes unchecked doesn't just fizzle out. It catches fire, and it burns.”

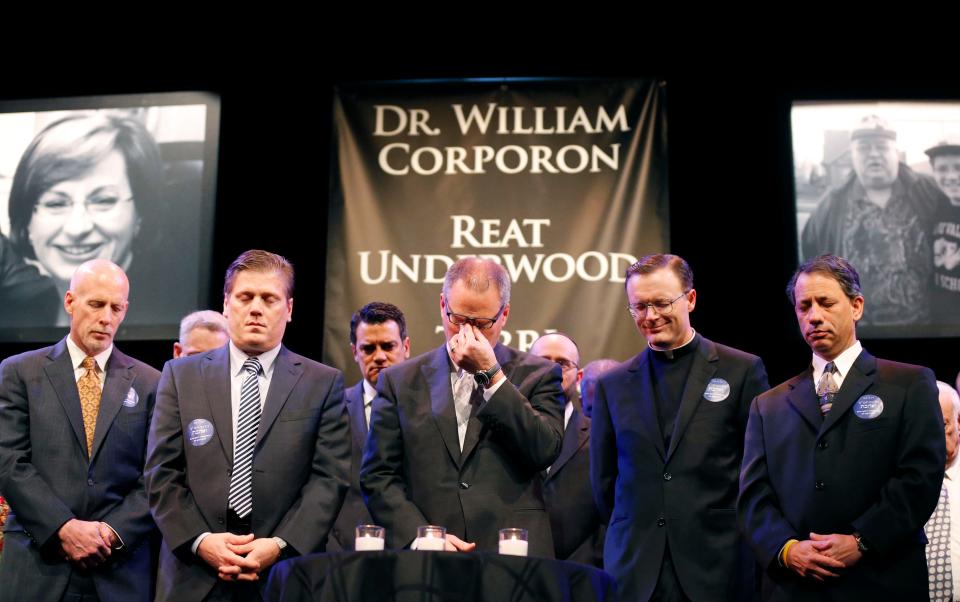

In April 2014, the Obama administration reestablished the committee after a spate of domestic right-wing attacks, including the murders of three people at two Jewish sites in Kansas by former Ku Klux Klan leader Frazier Glenn Miller Jr.

Then-Attorney General Eric Holder said the committee was needed to expand DOJ efforts to prevent hate crimes and other violent attacks by “extremists here at home,” including those radicalized via the internet. The group, which Holder said would include the Justice Department, the FBI and federal prosecutors, would coordinate with law enforcement nationwide.

Some hate watch experts say the fatal shootings by Miller, a lifelong white supremacist who had engaged in racist violence since 1979, underscored federal law enforcement's failure to proactively address the threat from right-wing extremists.

They also said the Justice Department's relaunch of the committee was more than overdue given that right-wing extremists had by then killed more people in the U.S. after 9/11 than al-Qaida-inspired militants.

Heidi Beirich, the director of the Southern Poverty Law Center's Intelligence Project at the time, recalled meetings with Justice and Homeland Security officials during Obama's tenure where she and other attendees repeatedly raised concerns about the growing right-wing threat.

"There were so many of us screaming from the rafters about it. We were saying, 'Look, you’ve got a metastasizing problem here, why aren't you putting resources at it?' " said Beirich, co-founder and chief strategy officer of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism and frequent expert witness before Congress.

"The response that we got over and over again is, well, those are just local and state criminal matters. Those don't rise to the level of terrorism, like what we see with these Islamic extremist groups," Beirich told USA TODAY. "I mean, it was just pure blinders on."

The Domestic Terrorism Executive Committee met quarterly in the last two years of the Obama administration, but its focus on right-wing extremism was derailed during President Donald Trump's term in office, according to current and former officials familiar with it.

Trump also neutralized Obama's Countering Violent Extremism Task Force and other efforts to counter the threat, interviews and documents show.

In September 2019, following several more mass casualty attacks, that task force's former leader, George Selim, warned Congress that right-wing extremism was “clearly and decisively” expanding across America and posed a grave threat. But the Trump administration was “moving in the wrong direction," he said.

“The question is not if another domestic terrorism tragedy will take innocent lives in America, but when,” Selim, a former senior Homeland Security official, wrote in his congressional testimony. “The gaps in our government’s ability to counter this threat are staggering and must be filled immediately.”

Three months after he was sworn in as attorney general, Garland unfurled what he said was the nation’s first-ever National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism. One key provision was familiar to some insiders: a plan to resuscitate the Domestic Terrorism Executive Committee.

"Our current effort comes on the heels of another large and heinous attack – this time, the Jan. 6 assault on our nation’s Capitol," Garland said during the June roll-out. "We have now – as we have then – an enormous task ahead: to move forward as a country; to punish the perpetrators; to do everything possible to prevent similar attacks; and to do so in a manner that affirms the values on which our justice system is founded and upon which our democracy depends."

His announcement came seven years after Holder vowed to do the same.

One current senior Justice Department official said the committee's fate says a lot about Washington's struggle to contain the threat: “We’ve been doing this for nearly 40 years now and the reason we’ve never been very good at it – and the reason we have all the problems that we have now – is because no one’s ever been in charge.”

Since Garland's June announcement, the domestic terror panel met in August, with plans to meet "multiple times" each year, a Justice spokesperson said.

"The DTEC is not an investigative or operational body and does not prosecute cases," the Justice spokesperson said, adding that it serves as a forum for federal and other law enforcement officials to "assess and share information about domestic terrorism threats and trends from their different vantage points."

Officials urged shift in attention to domestic threats

Conner Eldridge, who was the U.S. attorney in the Western District of Arkansas, shared the Justice Department official's concerns. Beginning in 2012, he said, he pushed to reestablish the committee, growing frustrated that the process took at least two years.

Eldridge, who later was tapped as the first co-chair of the committee, said he also urged top DOJ officials such as the head of the National Security Division – first Lisa Monaco and then John Carlin – to allocate more resources for domestic terrorism threats.

“I thought, this thing’s disproportionate to me; we have all these agents and all these resources devoted to IT (international terrorism), yet the risk in the Western District of Arkansas and other districts like it to bring the next Timothy McVeigh is far greater, given our past history,” Eldridge told USA TODAY.

Eldridge maintained that the Obama administration had as many as 300 National Security Division lawyers at the Justice Department, but only two specifically for domestic terrorism, both focused on prosecuting crimes rather than identifying potential threats. He also said he couldn’t find a domestic terrorism specialist on the White House National Security Council to work with.

By the time he left office in 2015, “no one in the U.S. Department of Justice was dedicated to looking proactively at the DT (domestic terrorism) threat and trying to come up with a strategy to prevent violence and crime" stemming from it, Eldridge said. "No one, and I say that with confidence.”

A Justice spokesperson noted that the department's National Security Division, created in 2006, was designed to integrate, coordinate and advance the "department's counterterrorism and national security work nationwide."

The division, the spokesperson said, was staffed with about 40 attorneys "trained and equipped to work on both domestic and international terrorism cases, as needed..."

Eldridge also said he urged the Obama Justice Department to designate a senior official to lead a more strategic and coordinated response to the rising right-wing threat. The position that ultimately was established in October 2015, domestic terrorism counsel, focused on policy matters, not operational strategy.

Tom Brzozowski, who has served in that position since it was created, has publicly defended the Justice Department’s record.

“This notion that domestic terrorists are getting a pass … isn't true,” he said in a 2018 presentation at the George Washington University Program on Extremism.

Vance, the former Alabama U.S. attorney, also served on the Domestic Terrorism Executive Committee. She said she wasn’t surprised it took so long for the Obama administration to reestablish it.

"Things just don't happen quickly” at the Justice Department, said Vance, who joined it in 1991. "There are a lot of incredibly important competing priorities. ... I mean, could it move faster? I guess."

Vance credited Obama’s Justice Department leadership, especially Holder and Monaco, for addressing the threat. The committee, she said, was finally hitting its stride when Obama was wrapping up his second term.

"It was a work in progress, and there needed to be more. We needed the FBI to focus more directly on the specific white supremacist terror threats," she said. "But I thought it was valuable work." Vance said she believed the effort would have "paid dividends" had Hillary Clinton, not Donald Trump, been elected in 2016.

“It's unfortunate,” she said, “that it seemed to just drift off as we left.”

Trump's 'very fine people' at Charlottesville

No single force did more to complicate the government’s effort to counter the threat of domestic extremism than the election of Donald Trump.

Following the deadly white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, Trump lauded the “very fine people” on both sides. In the aftermath of several mass shootings, beginning with the October 2018 massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, the president did little to discourage the spate of violence. Instead, he continued to sow discord by sounding anti-immigration and white nationalist themes.

“You can trace the growth of violent white supremacy in our times from August 2017 to Jan. 6, 2021,” said Raskin, who is also a member of a special House committee investigating the Capitol assault.

Trump, he said, “was able to accomplish for the far-right what they couldn’t accomplish for themselves. They went from being a marginal, reviled band of rag-tag soldiers in Charlottesville to being the stormtroopers of a march … that knocked over the U.S. Capitol and came within inches of overthrowing the 2020 presidential election."

One official on the receiving end of Trump's efforts to downplay right-wing extremism was Murphy, who had retired from the FBI and joined DHS after encountering resistance to his efforts to focus more on the domestic threat. He said he ran into roadblocks first as the FBI's chief of counterterrorism in Chicago and then as a top counterterrorism official at headquarters in charge of setting up a Countering Violent Extremism program.

From his vantage point as a top official at the DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis in 2018, Murphy saw the level of extremist violence skyrocket, especially as Trump fanned the flames of anti-government and white nationalist rhetoric.

Far-right extremism, violence and conflict soared as Trump used the White House as a bully pulpit to amplify anti-immigration and anti-government fears, and pressured appointees to focus on other issues.

Murphy filed top-secret whistleblower complaints three times, alleging in his last one that Trump administration officials broke the law, in part, by ordering him to downplay the threat posed by right-wing extremism.

The Trump administration also ordered leaders at the departments of Justice and Homeland Security to focus on threats from outside America’s borders – Islamic terrorists abroad and immigrants coming across the southern border whom the president falsely portrayed as being mostly criminals and rapists.

Instead of calling out the white nationalist threat, Trump and other officials, including then-Attorney General William Barr, repeatedly took aim at far-left groups, especially Antifa, a militant movement that opposes white supremacists.

Trump’s refusal to even acknowledge the domestic right-wing threat represented an about-face from the Obama administration.

Yet Obama officials faced political blowback of their own when taking steps to combat right-wing extremism.

When Holder proposed the reconstitution of the long-defunct domestic terrorism task force, he was careful not to single out any particular group, citing an “escalating danger from self-radicalized individuals within our own borders.”

Within days, Republicans pushed back. House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., said Congress had to ensure that the task force “won’t be used as another way to silence conservatives, including those who call for a smaller, more limited government.”

Something similar had happened soon after Obama took office. In 2009, a DHS intelligence assessment warned of a dramatic surge in right-wing extremists who were capitalizing on the election of the nation’s first Black president to “recruit new members, mobilize existing supporters, and broaden their scope and appeal through propaganda..."

Thanks to the Internet and social media, the report said, domestic extremists now had greater access to "information related to bomb-making, weapons training, and tactics, as well as targeting of individuals, organizations, and facilities, potentially making extremist individuals and groups more dangerous and the consequences of their violence more severe."

The report was prepared by the Department of Homeland Security's Extremism and Radicalization Branch and coordinated with the FBI. It concluded that “lone wolves and small terrorist cells embracing violent right-wing extremist ideology are the most dangerous domestic terrorism threat in the United States.”

But the DHS report created an uproar by singling out “disgruntled military veterans” as likely targets of recruitment by extremists who wanted to exploit their training and combat skills.

“To characterize men and women returning home after defending our country as potential terrorists is offensive and unacceptable,” then-House Majority Leader John Boehner said at the time.

Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano disavowed the document and apologized to veterans. The DHS senior domestic terrorism analyst behind the report, Daryl Johnson, later said he was pushed out and the unit fell apart.

"What worries me is the fact that our country is under attack from within, from our own radical citizenry," Johnson told the SPLC two years later. "Yet our legislators, politicians and national leaders don't appear too concerned about this."

In July 2015, a group of progressive lawmakers accused the Obama administration of continuing to focus on Islamic terrorism "while failing to devote adequate resources to right-wing extremism" despite statistics showing a sharp rise in attacks.

They called on Obama and DHS to update the 2009 report in the form of a new intelligence assessment on the right-wing threat, to reopen Johnson's unit and to stand up to Republicans who forced its initial shutdown. "This lack of political will comes at a heavy price," they wrote, citing the recent murder of nine people at a historic Black church in South Carolina by young white supremacist Dylann Roof.

The 2009 DHS report would prove prescient, as at least 65 military veterans are among more than 700 charged so far in the Jan. 6 attack, according to a USA TODAY analysis. A group launched in 2009 in response to Obama’s election, the Oath Keepers, now claims tens of thousands of members with backgrounds in the military or law enforcement and has become one of the largest anti-government groups in the U.S.

'The rhetoric was scary but there wasn’t that much we could do'

Many of the government’s challenges in confronting right-wing extremism are rooted in the FBI’s troubled past.

The FBI’s emergence from the shadow of the COINTELPRO political spying scandal spanning the 1960s and early 1970s was accompanied by new limits on intelligence gathering to guard against the improper surveillance of political organizations, civil rights groups and activists.

In the decades that followed, efforts to penetrate loosely affiliated anti-government militias, white supremacists and sovereign citizens often collided with constitutional limitations. Merely espousing extreme views and having an affinity for guns did not necessarily equate to criminal intent.

By the 1990s, “it was extremely difficult to get sources and undercovers inside without a clear indication that they were planning to commit crimes,” said Chris Swecker, a former chief of the FBI’s Criminal Division. “Simply because their ideology may have been repugnant did not mean that they were criminals.”

James Bernazzani, a former FBI SWAT and counterterrorism team leader, said the fiery rhetoric often never advanced beyond talk.

“They’d go out with a bunch of guns and camo and talk about overthrowing the world, go out and get s---faced and then get up and do it again the next day,” Bernazzani said. “The rhetoric was scary but there wasn’t that much we could do" unless they were committing, or taking steps to commit, crimes.

In 1998, in the midst of a supposed full-court press against domestic terrorism after Oklahoma City, Swecker learned something troubling: The bureau’s 56 field offices had cultivated few informants inside extremist groups.

“Some field offices reported having six to 12 live sources, and that was considered good,” he said. “A number of offices had zero. Unless (suspects) blew something up, they were hard cases to work.”

A current senior FBI official acknowledged the First Amendment obstacles to cultivating productive informants, but contended the bureau prizes the quality rather than quantity of those sources.

According to court documents, informants were key to recent extremists' arrests and last year's break-up of the alleged plot to abduct the Michigan governor. In that case, federal prosecutors referred to a network of "confidential sources" and "undercover agents" who helped reveal the scheme.

“Human intelligence collection is incredibly important," the official said, "especially when you think about our challenges with lawful access and the inability to get maybe what we need from an evidence standpoint with a legal document. ... You've got to find the right person with the right placement and access, and that could take not days or weeks, but years."

First Amendment protections, however, didn't hinder the fight against al-Qaida, thanks to the post-9/11 USA Patriot Act, which expanded the government’s collection capabilities against U.S.-based suspects with ties to international terrorist organizations.

9/11 transforms the FBI

Within minutes of al-Qaida's attack on Sept. 11, 2001, FBI agents, along with the rest of the U.S. government, mobilized in ways unprecedented in modern history.

Brian Murphy was no exception. After serving four years in the Marines and rising to first lieutenant, he had joined the FBI in March 1998, a month after Osama bin Laden issued a fatwa providing religious authorization for the indiscriminate killing of Americans and Jews.

Working on a drug squad in the FBI’s Manhattan office, Murphy was counting cash to be used in an undercover buy when a panicked receptionist told him to look out the window. The World Trade Center, just a few blocks away, was burning.

Out the door before the second plane hit the South Tower, he joined the counterterror response at ground zero and never looked back.

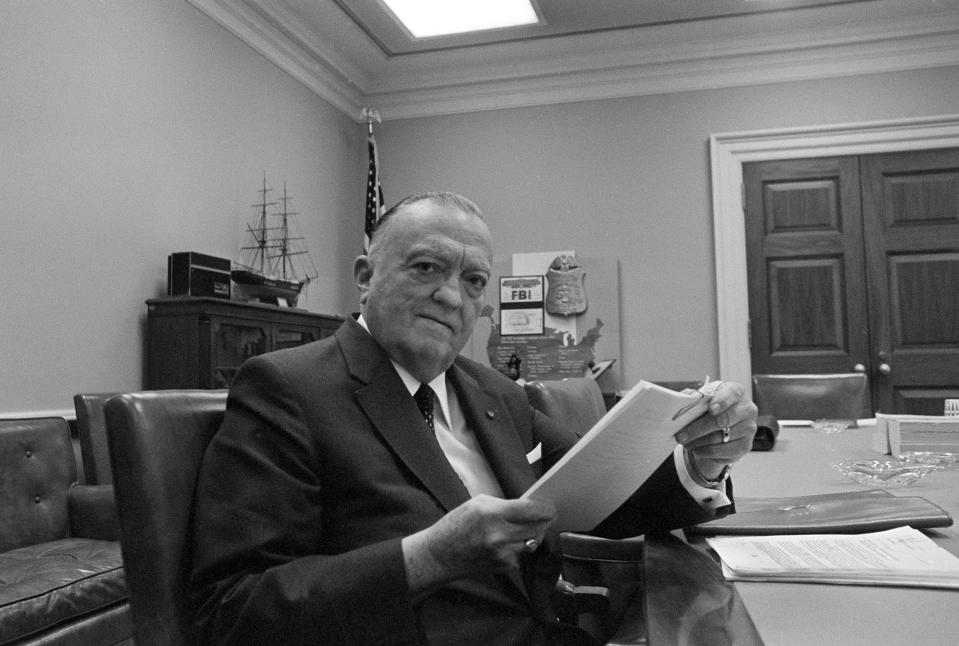

FBI Director Robert Mueller, on the job for just a week before the suicide hijackings, pivoted the bureau almost entirely to international terrorism.

“On Sept. 10, we had only 535 international terrorism agents around the world, with only 82 at headquarters," Mueller said in a 2003 address to the ACLU outlining the post-9/11 reorganization.

Within days, he said, almost 7,000 of the FBI’s agents, plus analysts and other support personnel, were temporarily redeployed to the investigation.

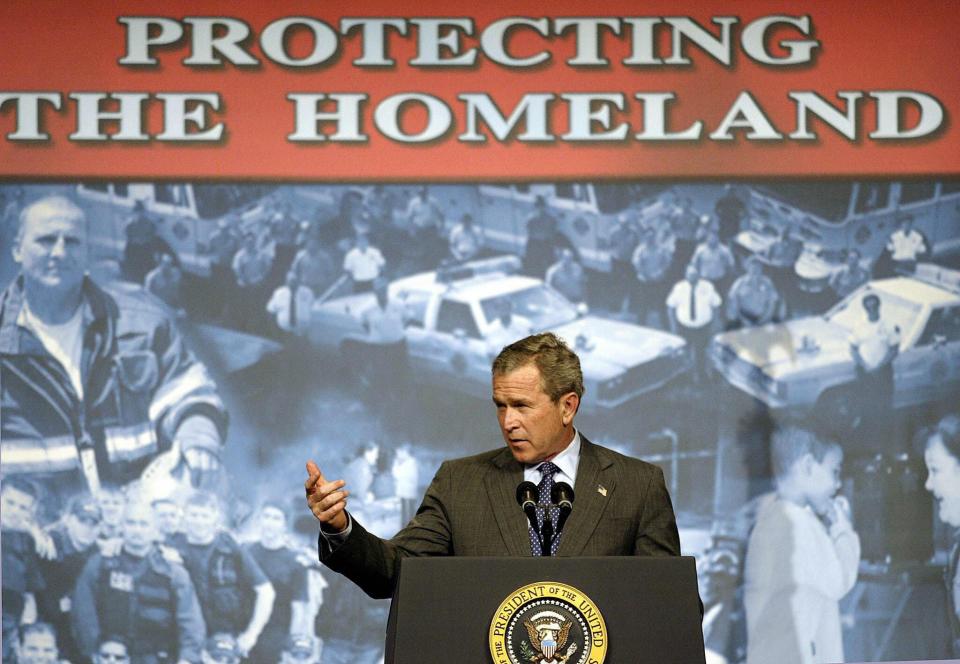

Over the next few years, the Bush administration orchestrated the creation of the Department of Homeland Security in the biggest restructuring of the national security system since the end of World War II.

A new Directorate of National Intelligence processed information streaming in from 16 intelligence and law enforcement agencies. A multi-agency National Counterterrorism Center served as the nerve center for the expanding U.S. campaign against Islamic terrorists.

Former FBI Special Agent Tom O’Connor, who spent 20 years investigating right-wing domestic terrorism before retiring in 2019, said those efforts were, by far, “a second-tier priority” after 9/11.

The shift, current and former officials said, created a void in which homegrown extremists without ties to international Islamic terrorism flourished in the United States as authorities focused abroad.

More than a decade later, O’Connor said, the FBI had "probably a dozen (international terrorism) squads in the Washington Field Office and one domestic terrorism squad. So that kind of tells you where it is in the pecking order.”

The redeployment of resources at the FBI to international terrorism also had a ripple effect on prosecutors at the Justice Department.

“There was a massive change in the types of cases they were focused on and even the types of investigations they were doing after 9/11,” said Christopher Shields, the author of a study by the University of Arkansas’s Terrorism Research Center. “After Sept. 11, it’s almost exclusively al-Qaida, AQIM (al-Qaida's North Africa offshoot) or ISIS-related, and very little devoted to the right wing.”

Sept. 11 didn’t just change Americans’ fears and the government’s efforts, it also changed FBI intelligence-gathering efforts to focus on thwarting future attacks – a dramatic switch from its traditional response to crime.

Before 9/11, “they were oriented toward getting information after the crime; they were very successful at investigating and prosecuting. The focus was not on getting ahead of terror,” a former Justice official said, adding that the agency’s systems for information sharing and predictive intelligence were “notoriously behind the curve.”

In the post-9/11 world, FBI agents and prosecutors were told to disrupt anything remotely resembling terrorist activity immediately. That was a big change from how they worked before, gathering evidence for big investigations that could lead to prosecutions and dismantling networks.

Not surprisingly, the new approach generated an explosion of cases – more in a single year by 2003 than in the previous decade, but most were for two-bit crimes like identification fraud and making false statements.

But it also resulted in a nearly 40% overall drop in the FBI’s use of informants and a roughly 25% decrease in its use of undercover agents in the immediate years following 9/11, according to the federally funded, nonpartisan Terrorism Research Center at the University of Arkansas.

Those were two of the three key methods, along with surveillance, deemed critical to stopping potential attacks in the planning stages. As a result, that decline hamstrung the government's ability to ferret out those bent on violence in the U.S., especially in the majority of pre-9/11 cases that focused on the homegrown domestic extremism threat, according to that 2012 report and interviews with current and former officials.

Carl Ghattas, a former executive assistant director of the FBI’s National Security Branch, said the bureau’s pivot after 9/11 was necessary.

“But the bureau has the depth and breadth to address threats on multiple fronts," he said. "I don’t think it is fair to say that the FBI neglected the domestic threat. Domestic terror cases were still worked during that particular time. You could certainly say that we could have done more, or it could have been done better.”

Hate groups thrive during the hunt for bin Laden

By the time Murphy was promoted to deputy FBI commander in Afghanistan in 2007, the bureau was virtually unrecognizable to anyone who knew it before 9/11.

When he reached Pittsburgh four years later, Murphy became aware of the right-wing domestic extremism threat. Then he was promoted to acting assistant special agent in charge of all FBI counterterrorism efforts there.

“You’re out of the foxhole and kind of looking at the big picture,” he recalled. “And I was like, we need to get engaged on this issue a lot more than we were doing.”

Murphy found that the intensity of antisemitic hatred was off the charts. More alarming, he said, was the widespread anger directed at the U.S. government from a variety of sovereign citizen adherents, militias and even white supremacists.

“It was just the level of rhetoric,” Murphy said. “They were all armed, which is not unusual for Pennsylvania. But the weapons that they had weren’t hunting weapons.”

By February 2011, the number of active hate groups in the U.S. topped 1,000 for the first time, according to an SPLC report. It said the anti-government “Patriot” movement had expanded dramatically for the second straight year too as the broader radical right showed “explosive growth.”

Among the accelerants, the SPLC said, were widespread resentment over the country's changing demographics, frustration over the lagging economy, the mainstreaming of conspiracy theories and propaganda aimed at minorities and the government.

Another was opposition to Obama. Law enforcement officials say his presidential candidacy – including a strong gun-control platform – united white supremacist and anti-government groups and helped them recruit and fundraise.

The volume of threat intelligence, including the interception of two assassination plots, that followed Obama’s election was unprecedented, as if “the election of America’s first Black president drew white supremacists and other (domestic violent extremists) out of the shadows,” recalled Patrick Burke, a former D.C. Metropolitan Police Department deputy chief who helped coordinate security for Obama’s 2009 inauguration. “There were death threats, bomb threats; I had never seen anything like it.”

Yet Murphy said his resources for international terrorism outnumbered those for domestic terrorism by at least six to one. That meant far fewer human intelligence capabilities, including surveillance, undercover agents and the cultivation of informants.

“We were well over-resourced on the Islamic threat,” Murphy said, describing what he said was an FBI mindset that hadn’t changed in the decade since 9/11. “We literally had way too many people doing it.”

Murphy discovered that he had little freedom to shift agents, analysts and other resources. So he did it in “onesies and twosies,” he said, which was far short of what was needed.

As recently as May 2019, Michael McGarrity, the FBI’s then-counterterrorism chief, told the House Homeland Security Committee that 80% of the FBI’s counterterrorism resources – and cases – were trained on the international threat, including people in the U.S. suspected of being connected to it.

Congress also played a role in the execution of that strategy. Of the $1.7 billion requested by multiple administrations for counterterrorism upgrades spanning the 2009 to 2021 budget years, $1.3 billion was approved. Of the $33.6 million requested for domestic terrorism-related programs during the same time period, $5 million was approved.

David Hickton, the U.S. attorney in Pittsburgh who worked closely with Murphy at the time, said the strategy was biased against Muslims.

“We were still in the framework established following 9/11 in which every mosque was potentially a criminal haven,” Hickton said. “It immediately raised the question: When we go over to the white community, what is the protocol there? It was just unbalanced.”

One factor: the FBI and Justice Department were full of conservative white males who didn’t view right-wing extremists as dangerous as left-wing and Islamic extremists, according to several experts who have studied those agencies’ counterterrorism efforts.

“Institutions of power that privilege whites in Western democracies are a big part of the problem,” said Anna Meier, a professor of politics and international relations at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. She has interviewed dozens of current and former national security bureaucrats and policymakers in the U.S. and Germany about their responses to domestic right-wing extremism and terrorism.

Meier argues that predominantly conservative, white male federal law enforcement officials in both countries believe they know terrorism when they see it, but they're blinded by implicit racial and political biases.

Particularly older officials, "when you talk to them about the Far Right and white supremacists ... it doesn’t register for them that that should be discussed in the context of terrorism. Their examples are overwhelmingly Islamist.”

Because of such biases many counterterrorism officials told Meier that "there is absolutely no political will whatsoever to talk about white supremacist violence, to do anything legislatively," she said.

Eldridge, Obama’s U.S. attorney in Western Arkansas, put it plainly. “There is, in my mind, a good old boy problem that is a systemic racism problem,” among some in federal law enforcement, he said.

Former FBI Director Louis Freeh, whose eight-year tenure ended months before 9/11, rejected that notion.

"Neither the First Amendment nor (federal law enforcement) diversity impeded ... investigations at the time," Freeh, now managing director and vice chairman at the consulting firm AlixPartners, told USA TODAY.

Government 'lost track of the threat'

Some within the Biden administration and Congress are weighing now whether to push for a domestic terrorism law to give federal authorities more authority to monitor, investigate and prosecute extremists of all political stripes.

But Michael German, a former FBI agent specializing in undercover investigations of right-wing extremists, told Congress in February that the debate over a statute obscures fundamental problems at the bureau and the Justice Department.

“All the necessary tools already exist,” testified German, now at the NYU Law Brennan Center for Justice, ticking off a list of laws and programs established to fight terrorism, including the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Forces.

“What the Justice Department has refused to do thus far, however, is to properly prioritize these investigations by producing a comprehensive national strategy to combat white supremacist and far-right militant violence,” he said, “or even to collect accurate data about these attacks across all its programs.”

Without the benefit of that kind of a coordinated strategy, the U.S. government lacks key details of the nature of the threat it faces, according to current and former law enforcement officials and lawmakers.

Such shortcomings have been identified for years by government watchdogs and counterterrorism experts, including many they said remain unaddressed.

A scathing August 2017 study by the Congressional Research Service, Congress' independent research arm, found that policymakers – including the lawmakers who asked for the report – couldn’t form even a baseline evaluation of the domestic terrorism threat due to many institutional problems.

Among them: federal agencies had no consistent way to describe domestic threats and respond to them. It also concluded that “there is no clear sense” of how many domestic terrorism plots and attacks the government had investigated or prosecuted.

Even before that, extremist watchdog organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Anti-Defamation League were frustrated by what they saw as governmental neglect. Their databases were brimming with alarming details of plots, plans and actual attacks.

One report issued by the SPLC's Intelligence Project, shared with law enforcement, described a broad list of right-wing targets. They included plots “to bomb government buildings, banks, refineries, utilities, clinics, synagogues, mosques, memorials and bridges; to assassinate police officers, judges, politicians, civil rights figures and others; to rob banks, armored cars and other criminals; and to amass illegal machine guns, missiles, explosives and biological and chemical weapons.”

“Most contemplated the deaths of large numbers of people,” the report said.

By 2011, the Department of Homeland Security, a critical link between counterterrorism leadership in Washington and local, state and tribal law enforcement, was effectively out of the right-wing extremism watch business, according to the Anti-Defamation League's Mark Pitcavage and other hate-watchers. “They lost track of the threat,” said Pitcavage, who has spent 24 years training federal, state and local law enforcement on terrorism and extremism issues with the FBI.

One programs Pitcavage worked on was the State and Local Anti-Terrorism Training (SLATT) Program, which provided no-cost federal training and resources to state and local authorities serving as the front line of defense against terrorism. Launched following Oklahoma City, it has been funded and defunded several times since.

The FBI and Justice Department had lost track as well, especially after 2008 when they stopped providing official data about domestic extremism investigations and prosecutions to the DOJ-funded American Terrorism Study. Without it, analysts could no longer provide authoritative advice on domestic terror trends, hot spots and which criminal charges were successful, according to Shields and others involved in the project.

Researchers at the American Terrorism Study scrambled to collect the data on their own. But, Shields said, “It really did away with any kind of transparency.”

The FBI told USA TODAY that data analysis has driven the bureau's terror threat assessments for at least the past two decades.

“But what the FBI does not do is investigate the ideology held by individuals, no matter how offensive," the bureau said. “Our challenge is to separate individuals who are exercising their First Amendment rights to talk about their views from those who intend to commit violence. We cannot conduct investigations unless we believe an individual or members of a group are moving from talk to violent action and violations of federal law. Intelligence and criminal conduct dictate what FBI agents investigate – not politics or other outside influences.”

"There is no doubt about it, today’s threat is different from what it was 20 years ago –and it will almost certainly continue to change," FBI Director Chris Wray told a Senate committee in September. "And to stay in front of it, we’ve got to adapt, too. That’s why, over the last year and a half, the FBI has pushed even more resources to our domestic terrorism investigations."

After the insurrection

What came at the outset of the Biden administration were dramatic acknowledgements about the threat that Trump had helped foment.

In May, the administration released an unclassified summary of an intelligence assessment that confirmed the sharp rise in right-wing extremist violence. The assessment concluded that the two most lethal elements of the domestic violence extremist threat are “racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists, and militia violent extremists.”

Of particular concern, it said, were “those who advocated for the superiority of the white race” and anti-government militias, whose threat “will almost certainly continue to be elevated throughout 2021.”

The Biden administration says it has responded vigorously: Immediately following the Jan. 6 attack, the FBI increased staffing and technical resources by 260%. The FBI did not provide USA TODAY with details it requested about where those resources had been increased.

A senior FBI official said the dramatic shift was part of ongoing threat assessments to identify where resources should be allocated.

"I think the perception that we have not applied resources is not correct," said the official. "We have applied resources based on that prioritization process, and really that's just driven by the intelligence that we have and what threat picture is painted each year."

Domestic terrorism-related arrests have outnumbered those of international suspects in three of the four years, ending in 2020, according to FBI figures.

The number of domestic terror investigations exploded over the previous 16 months from 1,000 to 2,700, Wray told Congress in September.

That same month, Murphy left government service for good after years of frustration with the lack of progress in addressing domestic terrorism, which caused tension with other FBI and DHS officials. "I felt the country was finally starting to take DT seriously," he told USA TODAY. But, "I felt I could achieve more by working with a private sector company" in the fight against disinformation and domestic terrorism.

A year earlier, Murphy said he'd been demoted by Acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf for refusing to manipulate threat intelligence, including on right-wing extremism, to support Trump's re-election effort. Wolf responded that Murphy's claims were "patently false," and that Murphy was reassigned due to credible allegations that agents under his command improperly collected information on U.S. journalists reporting on protests, which Murphy denies.

In recent years, after authorities said right-wing domestic terrorists were a threat on par with the Islamic State group, the National Counterterrorism Center expanded its purview. It now has a small unit to help the FBI and DHS on domestic extremism.

Now, “it’s not just militant Islamists but also militias in Michigan,” said Seamus Hughes, deputy director of the Program on Extremism at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and former lead National Counterterrorism Center staffer on U.S. efforts to counter violent extremism.

Eldridge, the Obama-era prosecutor, has stayed in touch with senior officials at the Justice Department since he left government. But nearly a year after Jan. 6, he said, he isn't aware of much meaningful progress in the fight against right-wing extremism.

“They must fix this problem once and for all,” he said. “I hope they realize that.”

Raskin, for one, believes Biden is on the right track. “I do believe that they are in process of assembling and deploying the resources that are necessary. But the magnitude of the threat is great,” he said. “The political scientists will tell you that the single biggest factor indicating a successful coup is a recent failed coup.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Federal agencies underestimated threat of domestic extremism for years

money

money